Words met by a Rustling of Fibers: Quinn Latimer in conversation with Laura McLean-Ferris

This fall, SIREN (some poetics) opened at Amant in New York, curated by poet and writer Quinn Latimer. The exhibition begins with the multiple meanings of the “siren,” in particular: an alarm during a state of emergency, or the voices that lured sailors with “honeyed song” in Homer’s The Odyssey. Though the siren has been popularly conceived of as part woman, part bird or fish, a new translation of The Odyssey by Emily Wilson pointed to the fact that no bodies for sirens had ever been mentioned in the original poem, just a song. Latimer’s exhibition, which hums with different visual and aural registers, looks to the voice beyond borders and binaries, and includes the work of Katja Aufleger, Patricia L. Boyd, Bia Davou, Sky Hopinka, Liliane Lijn, Bernadette Mayer, Rosemary Mayer, Nour Mobarak, Senga Nengudi, Rivane Neuenschwander, Mayra A. Rodríguez Castro, Aura Satz, Ser Serpas, Shanzhai Lyric, Jenna Sutela, Iris Touliatou, and Dena Yago. Here she discusses the making of the show with Laura McLean-Ferris, Topical Cream’s 2022 Editor–in–Residence.

Laura McLean-Ferris: How did you come to the voice of the siren as a force or sound around which this project would orbit? Has this idea been with you for some time? Was there a particular artwork or text that brought the voice of the siren into focus for you?

Quinn Latimer: I think I came to this idea of the siren both ambiently—I was hearing it in the distance for a while—and then directly, in a way that I couldn’t ignore.

I’m not sure the order of these things occurring, but a few years ago I was asked to write an essay for a book accompanying a Katja Aufleger show at the Tinguely Museum. I called my essay “The Signature of the Siren Is the Silence After,” and focused on a series of Katja’s works called Sirenen that came from her travels in the Al-Wakrah desert in Qatar. Not World Cup related! Qatar’s desert features the so-called singing dunes, which emit wild sounds: drones and blips, almost electronic, which travel very far. I started thinking of the Qatari dunes as the Eastern Mediterranean island meadows of the Homeric Sirens. In the original text of The Odyssey, the Sirens were never figured with or indicated by a body. They had mouths and information and offered a kind of total knowledge of everything on earth rendered in song form. Honeyed mouths that poured poetics. As Emily Wilson, the first woman translator of The Odyssey into English, wrote in a Twitter thread around that time: “The Sirens were cognition only.” I loved the rhythm and concision of Wilson’s tweet, its terse economy. It opened up a lot of ideas for me.

Wilson’s translation of The Odyssey came out then, but I was most interested in her reflections on the translating process. She noted all the tropes that previous Western male translators had built into the ancient text to make sense of it—the biggest one being the Siren story. These femme bodies had been written into the epic poem in order to make the Siren song’s intoxicating appeal legible and ideological. I was taken with this idea of constructing bodies like vessels to hold and withhold sound and voice. To corral voices and what they contained—the foreign and the hybrid, the nonhuman and the nonbinary, the female and some gendered premonition—within certain operations and systems: patriarchal, supremacist, literary, economic. Paradoxically, it reminded me of the making of our avatars today, both online and off, in poetry and art as in life.

I was also writing about the composer Maryanne Amacher at this time, and her work with otoacoustic emissions, those sounds created by your own ear, functioning as both instrument and speaker. These sounds seemingly born from one’s own head—which always seemed very mythic to me, like Athena birthed from Zeus’s cracked skull. To be honest, I was thinking about emergency in general, in a material and immaterial sense: sirens, war, violence, grief, warning systems, fear, anxiety, loss. It was a lot. And it still is.

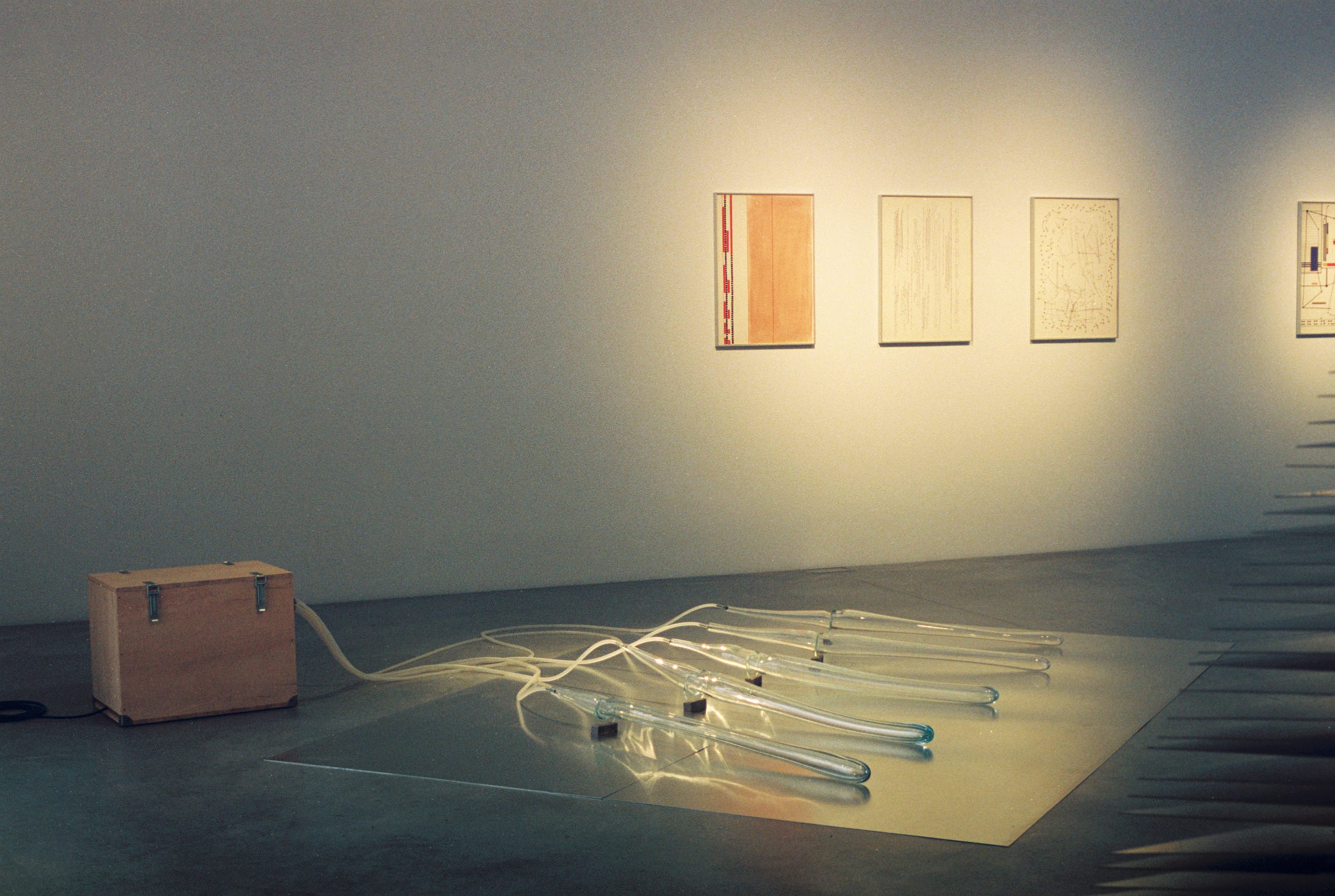

When I first visited the opening I had a very distinct sonic experience with Katja Aufleger’s glass organ pipes that were playing the sounds of the dunes when I was standing next to them. There were several people in the gallery talking and other sounds from artworks, but the glass organ started to break up the sound of the space and created rhythmic, audible glitches in the soundscape of the room. I experienced the sound as shattered and fragmented, which I think is what you are discussing in terms of Zeus’s “cracked head.” Is that phenomenon a known aspect to the work? Perhaps it’s a good place to discuss the overlaps between voice and music in the exhibition‚ the example that comes to mind is Mayra A. Rodriguez Castro’s Senti (2022), the wind chimes hung in the courtyard that are tuned to tones of the artist’s voice.

There is something about sound and song that gels and then fractures space, that puts its chaos into rhythm, then breaks, causing some glitch. I was reading Deleuze and Guattari’s “Of the Refrain” chapter with my students this week, alongside poems and prose by Adnan, Hartman, Duras, Plant, and Robertson, and the expression of rhythmic language is seemingly always related to space and territory, to the body spiraling within it. Katja used sand from the singing dunes in Al Wakrah to make the hand-blown glass vessels that function as her organ. Air is pumped into them; sound results. So the sound is not exactly a recording of the singing dunes but the sound of their material affected by air, which is also, in a sense, how the dunes’ singing works as well, with wind, speed, surface, grain. Her work is a beautiful, weird translation of the dunes. A bit synesthetic, like so much in the show. The grain of the voice, per Barthes, perhaps.

But to your larger question: the bleed of sound—and light and projected image—in the galleries at Amant was important, as was approaching sound in all its facets: spoken and written language, noise and music, recorded and improvised sounds. I wanted this subtle sense of polyphony; nothing was totally autonomous or crisp. You could register the sound works by Katja and Shanzhai Lyric and Nour Mobarak, and the soundtracks of the videos and films by Sky Hopinka and Aura Satz and Jenna Sutela—all their instrumental sounds or sung and spoken voices—but you could never hear any of them alone. Something or someone else was always answering: a call and response. Like you say, the galleries seemed to be measured out by these sounds, put into a rhythm, then taken out of it. This shifting, overlapping sound might be heard as you did—as glitch—or as bleed, or polyphony.

It is the same thing with light, though. Liliane Lijn’s prisms throw rainbows across Katja’s work on the floor and Rosemary Mayer’s works on the walls. Nothing remains untouched by other voices and their aesthetic signatures. This move between sound and light, voice and music, human and nonhuman sound, was important, as translation or transposition. I first asked Mayra, a poet and a translator, to make a series of sound recordings, because her voice is such a singular instrument. But she ended up making these bar chimes in Colombia, while visiting her mother, which approximated the lower and higher tones of Mayra’s voice. The resulting sculpture is vertical; its wind chimes are hung vertically on a horizontal bar. The whole thing is very anthropomorphic but also robotic. And its vocabulary of forms and materials is very economic. The sculpture is a kind of avatar, an attenuated body built to sound a voice—via its interaction with air currents. It is a speaker. Mayra recently did a reading with her work at Amant, which I imagined—from afar, since I was in Europe—as a reading for two voices, somehow. Or two bodies and one voice.

In the notes for SIREN (some poetics) you write: “Moving away from the cool, clinical, conceptual and mostly two-dimensional exhibitions that have so often stood for language and poetry as a visual art practice, in which the white cube stands in for the pale architectonic page, SIREN is situated in the dank earth and its kaleidoscopic ecosystems.” Though the exhibition is rooted in sound and voice, SIREN had a number of formal motifs that recur throughout the spaces. I’ll start by mentioning one—a triangular, pyramidal structure seen in dunes, sails, tents and Liliane Lijn’s Queen of Hearts, Queen of Diamonds (1980). How did you develop the visual language of the exhibition? I was struck by the way that the air moves through these forms, as well as a possibly etymological relationship between the Sirens from The Odyssey and words meaning “tie” or “bind.”

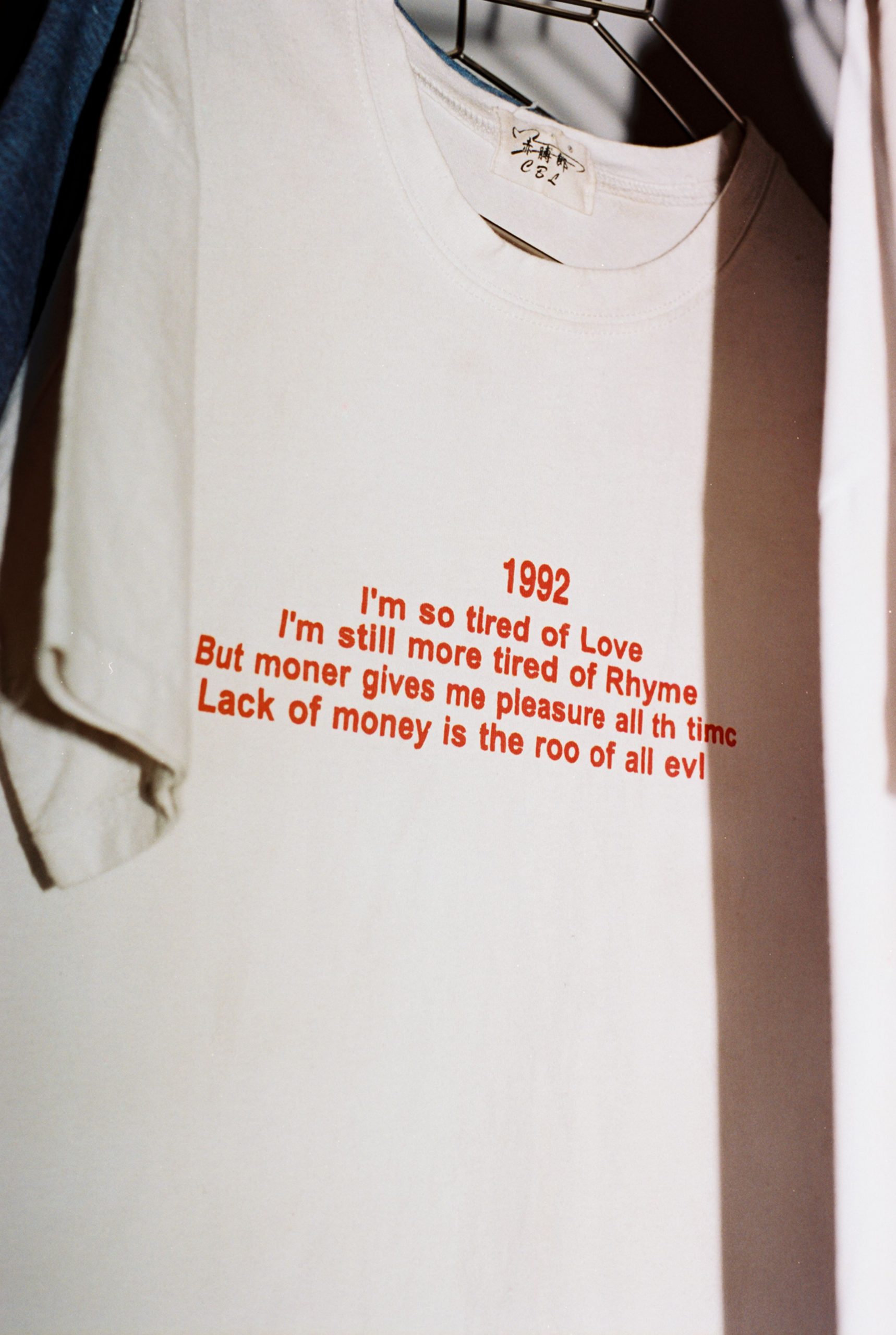

I love that you picked up on those repeating triangular sails and pyramidal forms, and the air and light that moves through them. I’m not sure one can talk about poetics without talking about repetition and rhythm and refrain, and I wanted to make this point formally, and materially. In my first notes for the show, which I was looking back at this week while I was finishing the essay for our book—coming out from Dancing Foxes Press next year—I made a note: “Sails as pages, all ground and air, all written. / Poem to object to moving images, all sisters. / Red and dark earth, pyramidal forms like sails, pale and pink and brown dunes, mouths.” Notes as lyrics, I guess. Some of the first works I started with in the show were the Greek artist Bia Davou’s Sails (1981), which are textiles embroidered with both opening lines from The Odyssey in Ancient Greek, and the Fibonacci sequence. Bia’s work on serial structures, binaries, cybernetics, the social world of literatures, linking technologies of epic poetry and weaving and nascent computer technologies, was central to my thinking. In the show’s title, it’s SIREN, not Siren or siren, because I was thinking of the word as a kind of early technology of the binary, and its breaking, for and from an ancient world. An ancient communications system of zeros and ones, early seafaring and epic poetry algorithm, woman and man, monster and man, nonhuman and human, song and poem, host and guest, the oral and the written, the foreign and the familiar.

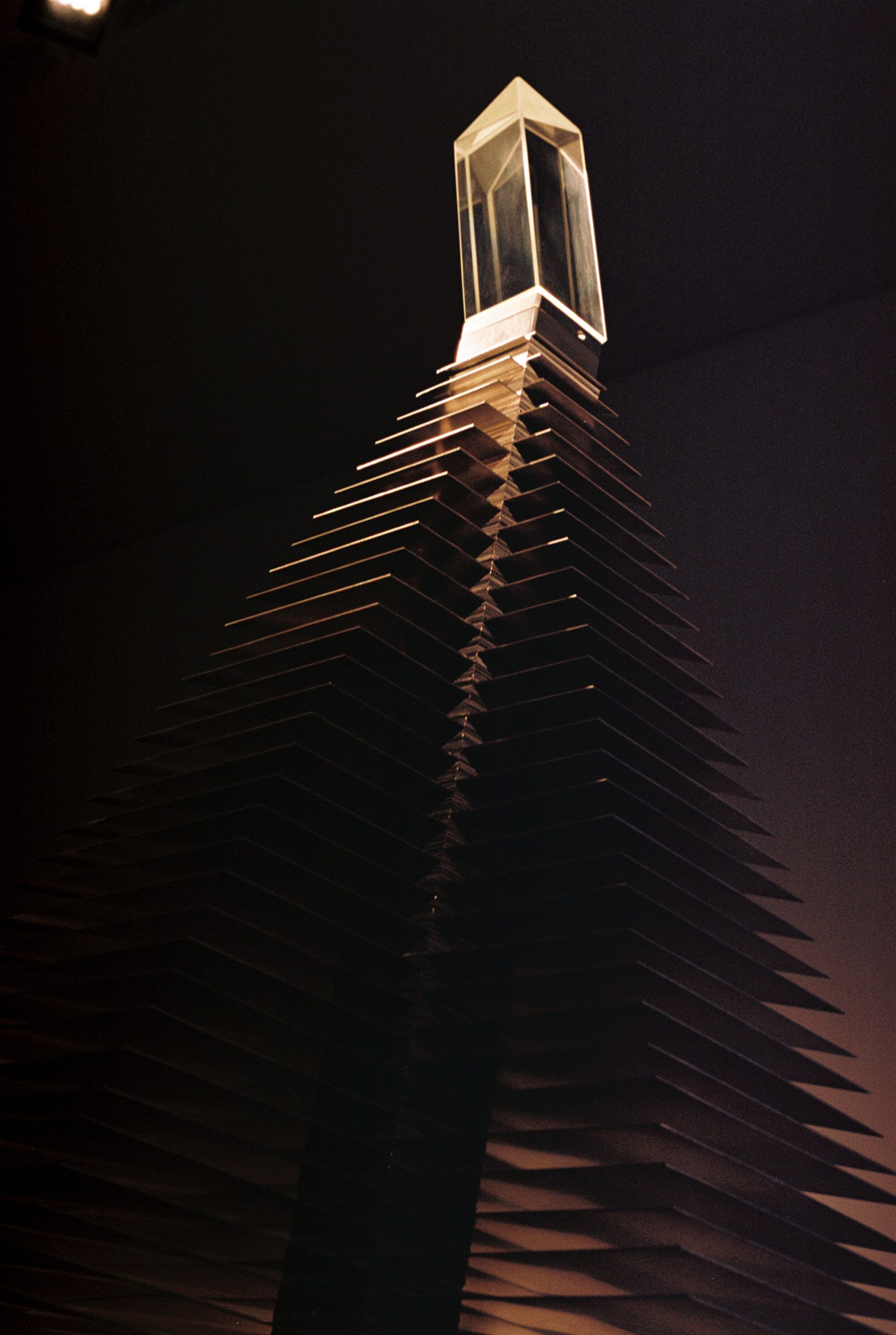

Liliane, whose pyramidal aluminum sculptures with prism heads really dominate the show, was also central. I first wanted to show her Conjunction of the Opposites (1986), this massive sculptural pair she made in the mid-eighties—all lasers, smoke, sound, and computer-controlled movement—but they proved wildly expensive to ship as inflation went crazy. Eventually I settled on her Queens from 1980, and I’m so happy we did. They change with the light—become hard then soft, opaque then transparent—and throw rainbows on the other works, on the walls and floors. They invoke both an anthropomorphic and a very alien intelligence. Though I was mostly thinking of the siren metaphorically, I also wanted to be a bit literal, a bit figurative. I always imagined standing sculptures punctuating the rooms. I wanted the autofictive, avatar-like assembly and intelligence we associate with them—or that I do. And to be confronted with the bodies we construct to make sense of our languages, our narrative conditions, our genders, our losses. I wanted the sirens in SIREN to be bodied as well as disembodied. And Liliane’s work—and thinking and life—is just so deep.

There were other very striking collaborations between human and non-human language and expressions in the exhibition, in works by Jenna Sutela and Nour Mobarak. Sutela’s nimiia cétiï (2018) was created out of interactions between a neural network, the movements of an extremophilic bacterium, and the Martian language channeled by Hélène Smith in the late 1800s. Here, we are offered a chance to imagine words from another time and another planet, and yet the ingredients to make this work are complex and prismatic, also, to stick with that form. Smith’s words, for one, acted as a kind of siren call for other artists, inspiring Surrealist automatic writing.

Nonhuman forms of communication seemed necessary to stage in a show about language and sirens. And all these popular science articles and books and Netflix shows were in the air: about how trees are said to speak to each other through their root networks, which send distress signals about drought, and how fungi speak through their hyphae. The idea that trees and fungi speak to each other seems to make people feel good—they talk and care for each other! just like us! or not! Maybe this is related to our current obsession with care, in the face of its systemic and very human lack. But it is compelling that we picture root and hyphae networks as lines of language like sentences and scripts, as articulate antennae spiraling and stretching out. We often reach into our body for our language, though, for our metaphors and similes—speaking from the gut, our heart in our hand, etc.—and those metaphors seem to apply to nonhuman life, too. That said, I love Jenna’s use of Smith’s Martian language—and I love Smith’s assertion that she was fluent in and could translate Martian language. Jenna’s use of the gut biome to create poetry is also central. And Nour’s work with voice and memory, orality and translation, and the desire, fatalism, and familial that streak through them. Both Jenna’s and Nour’s work have this formal rigor and punk, operatic, technological largess—it’s super moving.

How has the exhibition spoken to you in its assembly? I’ve been thinking lately about Lisa Robertson’s description of a “sense-textile” as a technology for apprehending the world and trying to rewrite it. What kind of writing or voicing has this been?

I’ve never read that description by Lisa Robertson, but I love it, although I have a feeling her textile is slightly more fashionable than the one I am imagining. Dries, Miyake, etc. But this relationship of text and textile, and the technologies by which they operate, run through SIREN pretty deeply. It’s a fabric at once woven and unraveling—Penelope as the other side of the Odysseus coin, perhaps. I’ve been thinking a lot about this short introduction that Christa Wolf gave for a lectureship on poetics that became her Cassandra project and book. To open her series of lectures, at the University of Frankfurt in the early ’80s, Wolf announced: “I cannot offer you a poetics.” Instead, she noted: “I want to set a fabric before you. It is an aesthetic structure, and as such it would lie at the center of my poetics if I had one.” When I read this I felt this shock of recognition, like she was talking about our SIREN exhibition, or that I had somehow curated it in response to some of the exact questions she was to lay out.

How do these questions figure in your work as a writer? Do you always write on a page? Where is the oral register in your poetry and writing most significant for you?

I came across this line the other day in The Water Statues, the new Fleur Jaeggy translation: “My words were met by a rustling of fibers.” I felt that. I think I am always writing to and through material—waiting for it to be met and to answer. To and through visual culture, films, images, objects, art and other. As a writer often at work in the visual art world, the performance of language—either via live readings or as scripts for moving images or as sound recordings—has become really central to my practice. In live readings, rhyme and refrain and repetition do a lot of work for the audience, their ability to receive and remember the text. The Odyssey, as an orally rehearsed and collectively composed and circulated epic poem that was created before written language existed in that part of the world, teaches us this pretty clearly. I often think I write between the page and the performance now, using the techniques and conditions of both to make my texts. I might have begun to rely on refrain and a certain tradition of orality in order to connect with my audiences, who often are not native English speakers, nor poets and writers as such, but now it’s just how I write. It’s how I think about language now and its fervently social worlds.

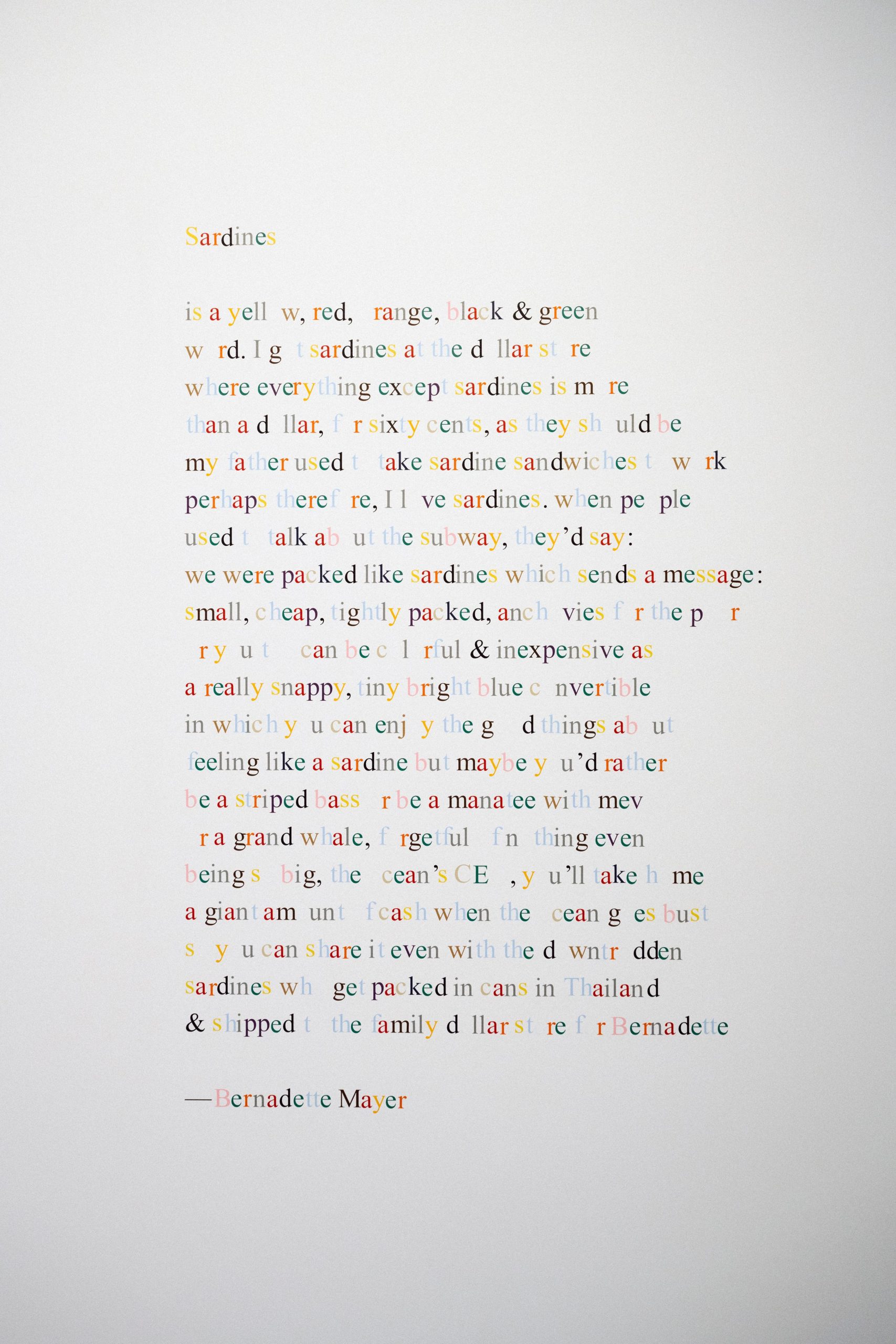

I wanted to end by discussing the work of Bernadette Mayer, who has sadly left our world since this exhibition opened. Could you discuss the process of working with Bernadette’s work in space and displaying her poetry within the color system for letters that she developed? Perhaps we can end on a poem?

It’s difficult to speak about, but Bernadette’s work is so immense, necessary, and exceptional, and just ever new. I still feel upset that I didn’t come to her work until so late. I met her when I was twenty and in college with Max, her son, but I didn’t really read her work until much later. The curriculum of my later poetry MFA in New York didn’t teach her work—it was a pretty mainstream and conservative program, looking back, in a way that was very common then but would be shocking now—and so I just eventually found her books on my own, and they were transformative. For the SIREN project, as I was thinking about epic poetry and questions of gender and duration, artistic forms as social forms, diurnal and nocturnal rhythms as literary rhythms, about language as a record of lived life, I knew Bernadette’s voice would be centered.

Her book-length epic poem Midwinter Day (1982) is such an important book. Inside it is a list of various forms of artistic practice that her sister, Rosemary Mayer, wrote at Bernadette’s request. For SIREN, I wanted from the beginning to bring Bernadette’s work into the same space as her sister’s, whose incredible oeuvre you’ve done so much, along with Max and Marie, to bring to a larger audience, Laura. I don’t think Bernadette and Rosemary had ever shown together before, in the same rooms, and their mutual movement between visual and written languages, poetry and visual art, conceptual and performative practices, seemed like a beautiful conversation to stage in the show, as parallel and sisterly and mutually supporting oeuvres. The idea was to show something that Bernadette wanted to do but had never really been able to, and the colored poems were one such project. She had made this color index for the alphabet, then mocked up one poem for an exhibition that had never happened. We took it from there. She was also interested in making a hologram of herself, but this proved too much for the possibilities we had. Someday it will exist, her and Tupac! So for the exhibition, we placed two of Bernadette’s poems in her color system—“Sardines” and “Marie says”—on the walls, one in vinyl, one printed, along with a projection of the alphabetic color index itself. When I was showing my father and family the show at Amant after the press preview, my uncle loved her poems so much. Afterward we went to dinner in Williamsburg and walked along the East River and he was reciting her poems from memory all night. This one was his favorite:

Marie says

Look tiny red spiders

are walking

across the pools

& just as I am writing down

tiny red

spiders are

walking across the pools

She says Mom I can just see it

in your poem it’ll say

tiny red spiders are walking

across the pools

Laura McLean-Ferris is a writer and curator based in Turin, Italy.

Quinn Latimer is a writer and occasional curator based in Basel, Switzerland, and Athens, Greece.

SIREN (some poetics) is open at Amant, Brooklyn, from September 15, 2022 – March 5, 2023.