Who Gets to Decide?: Cancel Culture and Museums

In “Who Gets to Decide?,” Habiba Hopson probes two very different examples of censorship in museums: one, a renowned biennial where public outcry led to the removal of an offensive painting after the exhibition had opened, and the other, a solo exhibition preemptively canceled by the museum for fear that the artist’s political beliefs would lead to financial retribution on behalf of donors and state funders. Drawing on her personal experiences working within institutions, as well as the guidelines stipulated by the National Coalition Against Censorship, Hopson considers whether—and how—museums can provide the proper tools and context for viewing difficult or controversial work. She asks, where does the authorial voice ultimately lie in the presentation and exhibition of art: with the artist, or with the institution? Who benefits from the complete removal of a work?

— Ebony L. Haynes, 2024 EIR

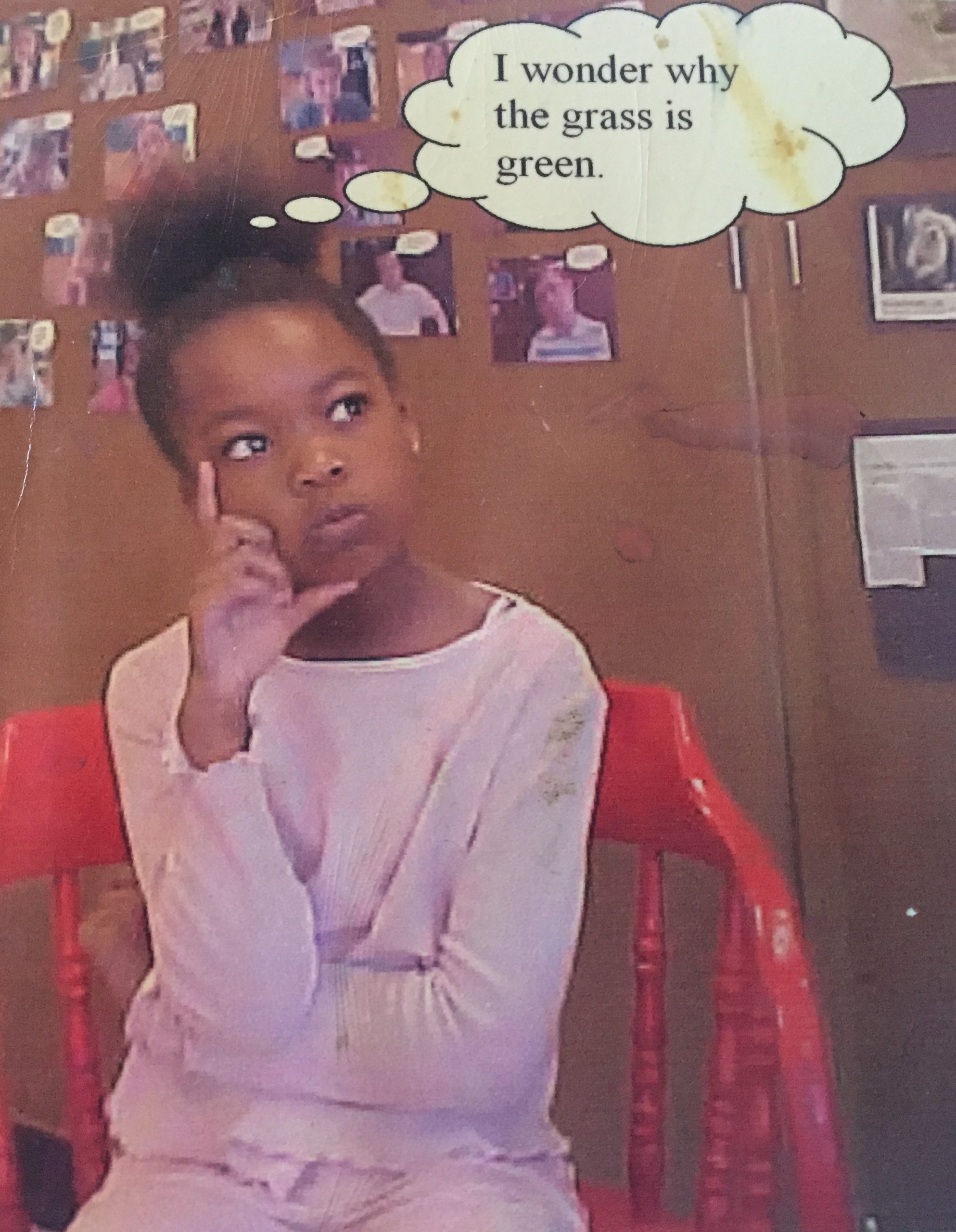

I love museums and have for much of my life. Growing up in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, I frequented the Carnegie Museum of Art, Carnegie Science Center, The Frick, and local community art spaces, among countless others, that became educational labyrinths of discovery, play, and introspection which undoubtedly contributed to my intellectual growth and critical thinking. Museums, unlike the classroom, generally forgo systems of evaluation that enforce a rubric of success and failure. Although exhibition didactics lay a necessary contextual foundation for understanding a work on view (the who, what, and where), they often leave us with unanswered questions (the why) to facilitate curiosity, generate interpretations, or challenge preexisting beliefs. By presenting real artifacts and immersive exhibitions of real-world issues in an open-ended manner, museums stimulated in me a hunger for wanting to know more.

During the fall semester of my sophomore year in college, I enrolled in my first art history course, “Introduction to Early European Art.” On the class’s first day, the professor, a generous storyteller, lectured on the birthplace of European art: Egypt. Furious, a fellow Black classmate and I voiced complaints about what we deemed as cultural appropriation of African antiquity. While the discipline of European art history attempted to trace cultural antecedents, what I gleaned instead—as an eager eighteen-year-old student—was an obvious act of seizing northern Africa’s rich history. Little did I know at the time, my critical engagement with the survey’s syllabus would manifest through the topic of my senior undergraduate thesis, where I further explored the lack of scholarship surrounding Black figures in canonical art historical images. Despite my frustration at the discipline’s proliferation of Western epistemes, therein laid an opening—which countless scholars and artists have rummaged through—for addressing historical disregard.

As complex as it is to engage with visual history, scholarship and generative discussion aid in contextualizing historical events, a political or cultural climate, and the intricacies of the human experience. Art allows us to visualize the good, the bad, and the ugly, and museums provide a public environment to not only categorize and store these relics, but also to make connections between, argue against, foster dialogue around, and venerate art history. When Topical Cream Editor-in-Residence Ebony L. Haynes invited me to contribute a piece on censorship, I could not help but question my own positionality as a museum worker and consider headlines of museums choosing to cancel solo artist exhibitions or removing the work of artists under scrutiny for political beliefs. I began to ask myself, why are shows canceled or postponed and who gets to decide? Do museums, as not-for-profit entities in service of the public, have a responsibility to expose the rough edges of history and the present moment? Is it realistic to assume that challenging conversations and debates can stimulate meaningful dialogue, and dare I say—change? I hope to explore these questions through two scenarios—first, the protest and call for destruction of Dana Schutz’s Open Casket at the 2017 Whitney Biennial, and second, the cancellation of Palestinian artist Samia Halaby’s exhibition at Indiana University’s Eskenazi Museum of Art—alongside my own evolving views, as a means to explore the complex situation that museums find themselves in vis á vis censorship. Justifying the cancellation of exhibitions that challenge controversial topics as “visitor protection” leads us down a potentially sheltered path. I am no way in favor of deliberately courting controversy for the sake of arousal, but if museums disagree with and decide to censor an artist or the subject matter they propose rather than expose the rugged edges of history and of the human experience, then we may risk widening the “us vs. them” binary and narrow our perception of what lies on the other side of our own beliefs and experiences. The censoring of art and cancellation or postponement of exhibitions has long existed in the art world and beyond. To help combat censorship, organizations like the National Coalition Against Censorship (NCAC) appeal to institutions such as museums, schools, publishers, entertainment industries, and individuals to embrace and uphold the democratic view that free expression is a fundamental right. For the past fifty years, NCAC has sought to “encourage and facilitate dialogue between divergent voices and perspectives, including those that have historically been silenced.”1

“Do museums, as not-for-profit entities in service of the public, have a responsibility to expose the rough edges of history and the present moment? Is it realistic to assume that challenging conversations and debates can stimulate meaningful dialogue, and dare I say—change?”

Interestingly, NCAC emerged in response to a 1973 Supreme Court ruling that stated that speech or expression deemed “obscene” was not protected by the First Amendment. Obscenity, in this case, directly referred to pornographic material. But the term “obscene” was later broadened to include various bold artistic interpretations of gender, sexuality, and personal and collective trauma. In the early 1990s, during the height of the Reagan-Bush culture wars, a group of visual and performance artists who came to be known as the “NEA Four” (Karen Finley, John Fleck, Holly Hughes, and Tim Miller) lost federal funding because their work, queer or feminist in bent, was deemed “indecent.” Evidenced then and continuing in the present, charges of obscenity are now deployed to censor confrontational subject matter, often generated by the historically marginalized. But completely removing, or worse, destroying that which is hard to deal with, instead of encouraging viewers to arrive at their own individual analyses, feels dangerous. When the seventy-eighth iteration of the Whitney Biennial opened to the public in March 2017, white artist Dana Schutz’s painting Open Casket (2016), an abstracted depiction of the slain corpse of Emmett Till, triggered outcry online and protests in the museum’s galleries. Shortly after, several stakeholders in the art world published a call to action for the Whitney to not only deinstall Schutz’s work but to destroy it (a request the Whitney did not meet). “The painting should not be acceptable to anyone who cares or pretends to care about Black people because it is not acceptable for a white person to transmute Black suffering into profit and fun, though the practice has been normalized for a long time,”2 the letter declared, reinforced by Black artist, writer, and curator signees. I agreed with the text’s demands at the time to censor and destroy Schutz’s painting, and I questioned the decision made by the Biennial curators—professional lodestars whom I so aspired to follow after—to include the work in the show in the first place. Was this a field, which still seemed devoid of representation and focused on satisfying non-Black artists and audiences, that I could actually see myself in?

Reading artist and professor Coco Fusco’s response to the Schutz controversy galvanized me to rethink my initial objection to Open Casket’s inclusion in the Whitney Biennial. Fusco, whose writing and practice I had been introduced to that same year in a spring semester contemporary art history course, contended that “the argument that any attempt by a white cultural producer to engage with racism via the expression of black pain is inherently unacceptable forecloses the effort to achieve interracial cooperation, mutual understanding, or universal anti-racist consciousness.”3 Art history is, as artist Kara Walker reminded us through a now-deleted Instagram post about the Schutz painting, “full of graphic violence and narratives that don’t necessarily belong to the artist’s own life.”4 Reflecting on this historic art world event, I contemplated how (and if) artists—of all races—should situate racial history in their practice. The Biennial curators might have included Schutz’s Open Casket for this very reason, yet it remains clear that the marginalized opinion—the Black audiences who voted against the work of a white artist—was ultimately ignored. With its ensuing heated backlash, the Whitney’s display of Open Casket questioned the need for supporting Black artists, raising concerns over artistic freedom and cultural ownership and, perhaps more interestingly, whose artistic voices are embraced by the field at large. Such cataclysmic discourse, which reverberated across the cultural landscape, has no doubt caused institutions across the world to evaluate their motivations for choosing to show—or not to show—an artist’s work. And while the 2017 Biennial pushback was colossal, reviewing later museum initiatives—such as MoMA’s 2018–19 reinstallation, which, for the first time, scrapped the “Whiggish movement-by-movement logic”5 of conventional permanent collection hangs to pair works by artists such as Faith Ringgold with Pablo Picasso—provides critical evidence that institutional change, though slow like coals burning over a hot fire, is inevitable. So, why not lean into the chaos (where necessary), for the unequivocal pivot toward transformation?

The 2017 Whitney Biennial controversy centered on an artwork, not on the personal life or beliefs of an artist. But when crisis develops in the artist’s own world, how must a museum react? To unfold this query, I turn to the cancellation of Palestinian artist Samia Halaby’s exhibition at Indiana University’s (IU) Eskenazi Museum of Art in December 2023. Even though this artist herself was a student and teacher at the university, the museum chose to cancel her exhibition in public denouncement of her political views about the unfolding crisis in Gaza.6 Similar in outcome to the 2017 Whitney Biennial, wherein the museum advocated against censorship at the cost of backlash from the Black community, IU’s decision to cancel Halaby’s exhibition reifies historical tendencies to censor individuals of historically underrepresented groups. A few months prior to the exhibition’s cancellation, state Representative Jim Banks threatened to pull federal funding from the university due to campus-wide concerns of antisemitism, in a move recalling the NEA Four decision thirty years earlier.7 Halaby’s social media posts on the Israel-Palestine conflict centered on her support for Palestinian liberation and indignation at Israel’s adoption of brute force, with no trace of antisemitic rhetoric. Nonetheless, the museum chose to withdraw Halaby’s three years in the making (and the artist’s first U.S. retrospective) exhibition. The academic museum, careful not to provoke Rep. Banks and other financial backers, equated Halaby’s rejection of the killing of Palestinians and her homeland’s destruction to an antisemitic sensibility, thereby ruining any chance for student visitors to approach the nearly ninety-year-old artist’s expansive abstract painting practice.8 But is not a college’s mission aimed at academic freedom and directing students to adopt a diversity of thought? When did commitment to an artist’s practice equate to a presumed endorsement of their opinions? Rather than rescind Halaby’s show, perhaps IU could have invited students and professors to partake in a period of organized and focused discussion of the artist’s life and practice, and how her peripatetic childhood after being exiled from Palestine later led her to employ abstraction as a tool for producing analog and computer-based paintings. I wonder, in this instance, if the NCAC’s suggested procedures for managing controversy, directed at identifying and contextualizing Halaby’s work rather than privileging a university’s ever-troubling financial situation, might have eventually proved useful for the developing critical minds of promising IU graduates.

These are complicated case studies and queries, all of which are wrapped up in the sustainability of museums, being that they directly rely on foundation and individual giving, as well as visitor approval. As much as museums can usher profoundly educational and transformative experiences for viewers, most require capitalism; they are not-for-profit entities that depend on the generosity of profitable funders and ticket sales. For this reason, they sometimes choose to appease, rather than stand behind the robust exchange of ideas. When the former becomes a priority, I wonder if mutual understanding can exist. Is it naïve or perhaps paradisical to imagine a world in which both justifiable anger and compassion can speak alongside one another? And what better place to do so than a museum, a space that, in theory, is expected to privilege goers of all creeds and cultural backgrounds, where one can make sense of the human experience alongside art history. Only time will tell whether courage can be found in the act of cancellation, or through the decisions of the artist, curator, director, and patron to keep going, amidst chaos, with the hope of stimulating momentous change.

Habiba Hopson is a curator and writer based in Brooklyn, NY. She’s currently senior curatorial assistant at the Studio Museum in Harlem, where—along with hosting the Museum’s first podcast New Additions—she supports the research and planning of curatorial projects for the Museum’s new building.

NOTES

1. “Mission and History,” National Coalition Against Censorship, https://ncac.org/about-us.

2. Hannah Black (with co-signatories), “OPEN LETTER,” 2017.

3. Coco Fusco, “Censorship, Not the Painting, Must Go: On Dana Schutz’s Image of Emmett Till,” Hyperallergic, March 27, 2017, https://hyperallergic.com/368290/censorship-not-the-painting-must-go-on-dana-schutzs-image-of-emmett-till/.

4. Calvin Tomkins, “Why Dana Schutz Painted Emmett Till,” The New Yorker, April 3, 2017, https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2017/04/10/why-dana-schutz-painted-emmett-till.

5. Jason, Farago, “The New MoMA Is Here. Get Ready for Change,” The New York Times, October 3, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/03/arts/design/moma-renovation.html.

6. Theo Belci, “US museum under fire for cancelling Palestinian artist’s retrospective,” The Art Newspaper, January 12, 2024, https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2024/01/12/indiana-university-cancels-palestinian-artist-samia-halaby-retrospective#.

7. Jeffrey C. Isaac, “Congressman Jim Banks’s Pressure on Indiana University Police Antisemitism is Duplicitous and Dangerous,” The Nation, November 29, 2023, https://www.thenation.com/article/society/jim-banks-indiana-university-antisemitism/.

8. Maggie Hicks, “When Threads Become an Excuse to Muzzle,” The Chronicle of Higher Education, February 6, 2024, https://www.chronicle.com/article/when-a-threat-becomes-an-excuse-to-muzzle.