Whitney Claflin’s safe and unbound spaces

Whitney Claflin’s work transcends conventional boundaries, inviting viewers into a realm of profound imagination and expression. Although she primarily identifies herself as a “painter’s painter,” she combines traditional painting techniques with found objects, poetry, and live events to weave together contemporary and personal narratives. Each piece—be it a painting, sculpture, installation, poem, or otherwise—is an experience for both the viewer and the artist, a testament to her ability to challenge traditional notions of art and aesthetics while using the history of painting as an orientational lens.

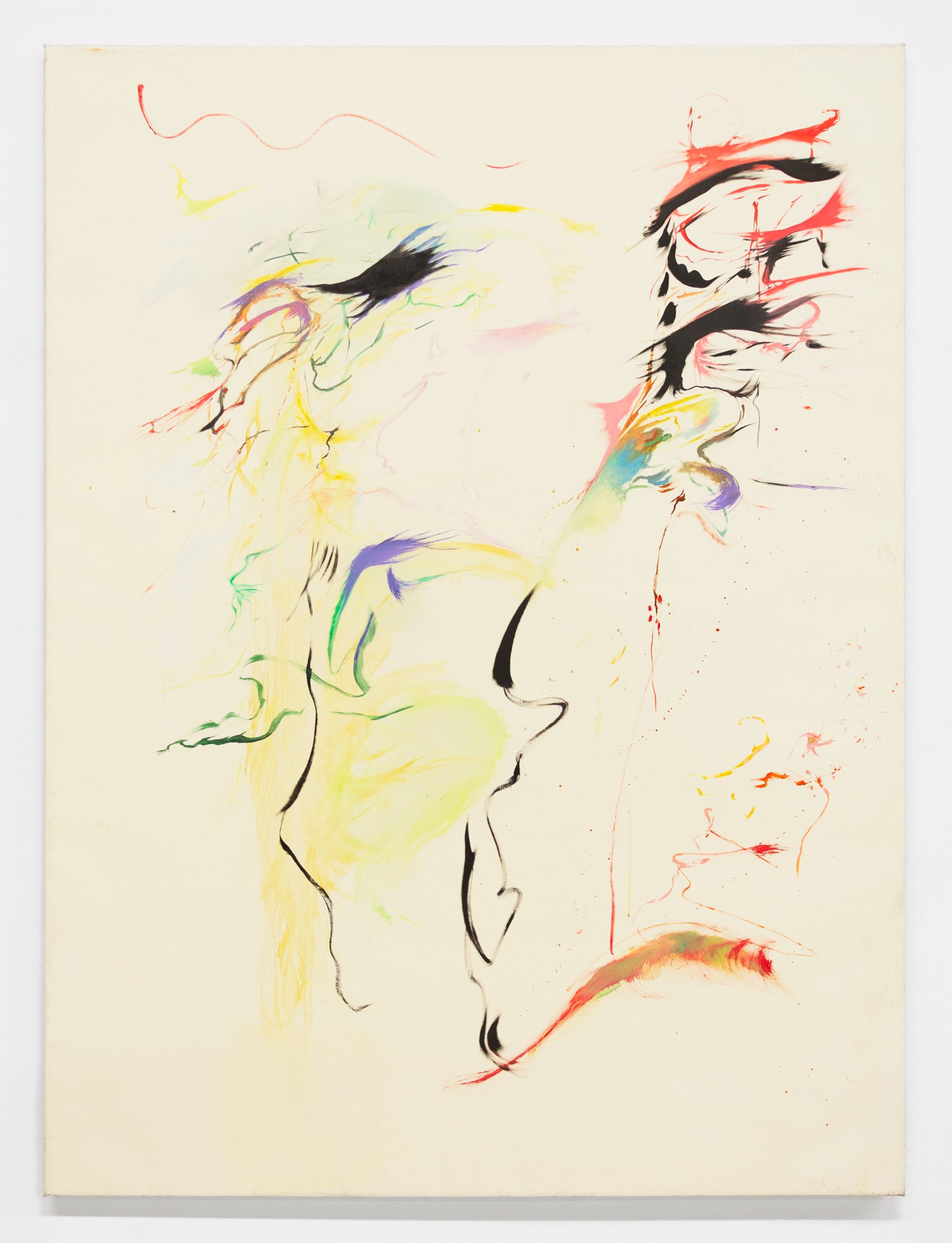

Claflin received her BFA from the Rhode Island School of Art and Design and MFA from Yale University School of Art. At both schools, she initially focused on figurative painting. At her core, she admits she’s deeply engaged with painting’s traditions and history, but she also found herself wanting to break free from those limits as well as the limits imposed by institutional and commercial frameworks. To do this, she began experimenting with things like her in-studio lighting and retiring control of the brush during graduate school. She painted with different colored lights above, allowing her to explore the relationships between hues and values anew—and to create paintings that, she says, she never would have composed in daylight or under regular white lighting. Seeing them in a literal different light, this approach also changed her relationship to gestures and textures. “It was the first time I was able to feel that good loss of control,” she says. “I surprised myself.” She began using found objects and painting abstract forms in graduate school, too. “It made me feel like I was learning how to paint again because it became so open-ended,” she says.

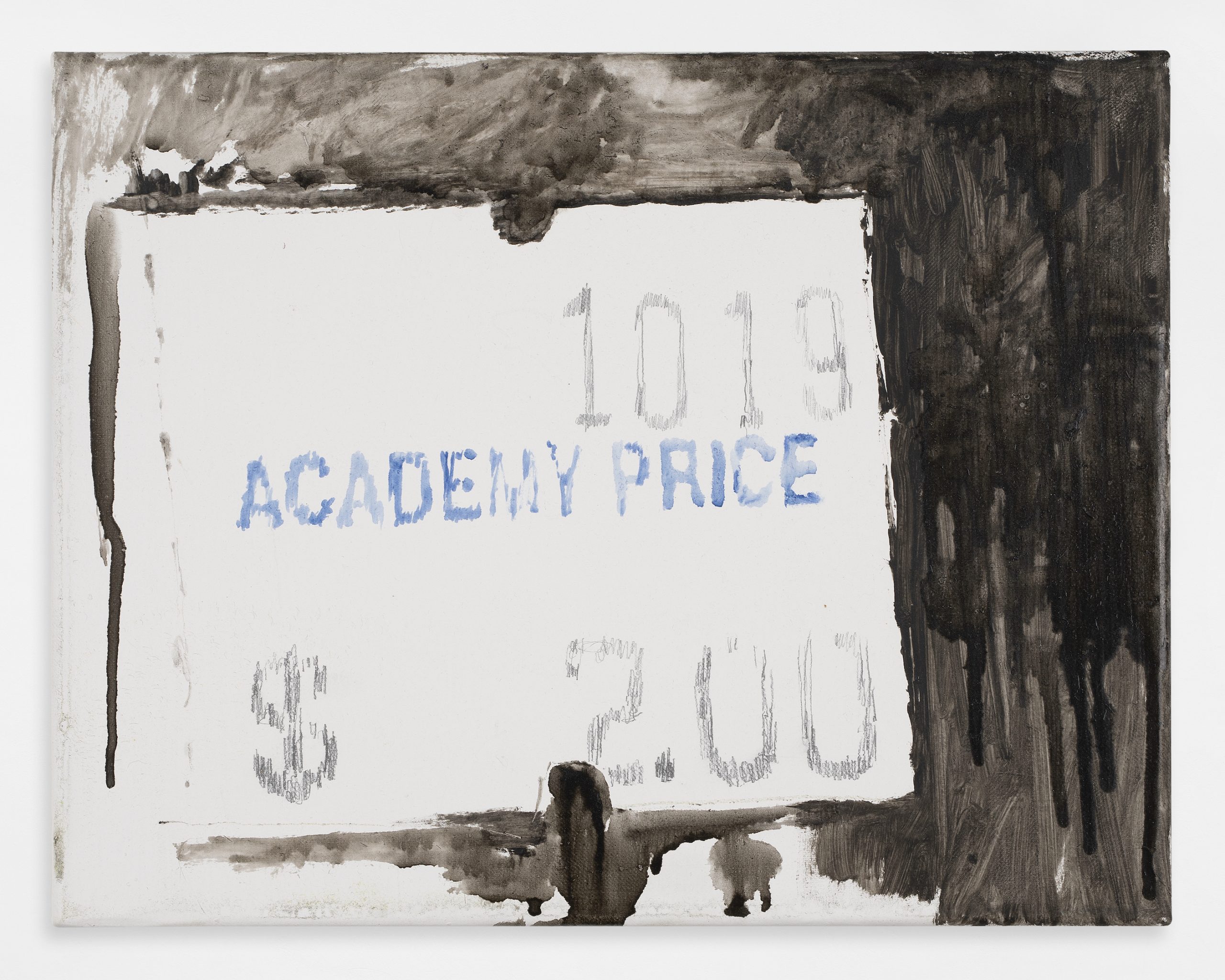

When Claflin moved to New York in 2009, she felt a sense of anonymity and, in turn, a feeling of artistic freedom that led to even more experimentation. At the same time, the cost of living in New York meant that she had to work in a smaller studio on a more intimate scale, and the price and scarcity of materials drove her creative direction. Like the Capitalist Realist artists in Germany in the 1960s, Claflin explored materials like “found fabrics and old clothes, preserving the intimacy or delicateness of fabrics, distinct from the conventional use of linen or canvas.” For example, two paintings from 2019, Final Drop and Ten Nineteen, speak to resale markets and are made on found fabric surfaces, with the first referring to reselling coveted clothes and the latter referencing used records and Discogs reseller culture in New York. But in the end, she continues, “you don’t know the paintings are made on an old skirt because they’ve been primed so much that they become almost like sculptures.” The freer mindset she adopted through both experimentation and her newfound space constraints became the backbone of her artistic practice.

Currently, Claflin is in Monchengladbach, a city in North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, with Borderland Residencies. Here she is exploring themes of nostalgia and pushing her work in new directions. She’s returned to working with larger scales and is also experimenting with light again—albeit this time through the use of blacklight. During the day, she creates work with neon tissue papers and opaque paints, which she then reexamines in the dark with a blacklight. Furthermore, she’s adorned her temporary studio with Christmas lights and lava lamps, the latter of which help calm and center her. “I meditate with the lava lamp, it brings me to a better place,” she says.

In many ways, the residency has also connected her to the artistic lineage of the Rhineland. Reflecting on her early influences, she remembers that she often listened to Krautrock, an experimental rock genre from West Germany popular in the 1960s and ’70s. Bands like Can, Neu! and Ash Ra Tempel led her to visual artists, namely Martin Kippenberger, Gerhard Richter, and Isa Genzken. She also recalls her admiration for Sigmar Polke: “He is probably the most important figure to me that is associated with that area.”

Sometimes her works might evoke or subtly reference artworks by these artists, but such impressions are fleeting. Stranger Danger (2020), for example, is a photocopy of one of Claflin’s graphite drawings of a close-up of a tie clip, an image taken from a still from Alfred Hitchcock’s 1951 thriller Strangers on a Train; Polke, too, used motifs from Hitchkock’s films. Also summing ideas related to Capitalist Realism is Mime in a Merry-Go-Round (2020), a sculpture comprising a mannequin wearing a custom shirt and a found skirt, bag, and bra, as well as headphones playing music. While the soundtrack includes a piece by Wolfgang Voigt, a notable Cologne influence, Claflin’s work has been updated to address today’s concerns: the cheap plastic bag covered in dark paint carried by a mannequin can be seen as a nod to contemporary luxury fashion labels who, by simply applying their logo, transform banal tote bags into thousand-dollar handbags.

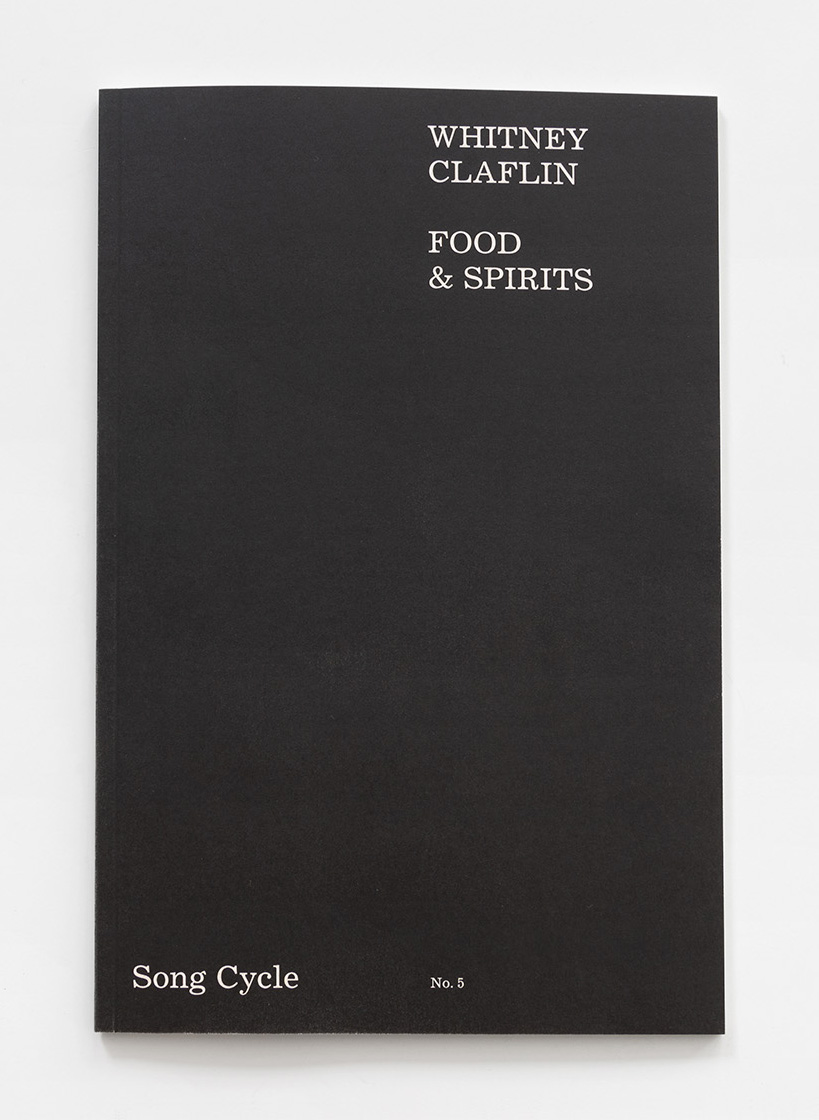

Another important element of Claflin’s practice is the power she finds in words. Many of her sculptures and paintings include collaged phrases from words cut out of magazines. Jacqueline (2022), for example, features a mannequin bust wearing big bug-eyed sunglasses with magazine cutouts creating the phrases “that surprised me.” and “forget how,” one on each lens. She also writes her own poetry. Last year Claflin published Food and Spirits, a book of new writings created between 2015–2022 that focuses primarily on things related to food, drinks, and ghosts from her past.

Making my way through a banana,

On the 1 train.

Making my way downtown

On the 1 train,

I’m around Christopher.

And I know one thing…

All the love that ever could be,

All sex,

A muted mystery.

An embarrassing afterthought in the shower.

Once it’s in my stomach, it feels reassuring.

But in my mouth,

No matter how perfectly ripe,

Leaning green even,

It feels mealy.

—“Subway Breakfast” in Food and Spirits (2022), Whitney Claflin

Beyond her poetic musings and visual works, Claflin’s practice comes full circle in her skill of bringing people together. Her exhibitions become safe spaces, places where both she and the viewers feel comfortable enough to be vulnerable and connect on a deeper level. In 2017, during her exhibition Just Disco at Real Fine Arts in Brooklyn, she held a performance, Raised in a Jail, in which she presented readings every Sunday while making grilled cheese sandwiches for the audience. Though perhaps unbeknownst to visitors, through the act of making these sandwiches, Claflin confronted negative associations from an abusive domestic experience she had previously endured while simultaneously offering comfort and nourishment to others. In 2022, during a book launch for Food and Spirits at Loong Mah Gallery, Claflin read through the book, cover to cover, at a rapid rate, accompanied by a three-gallon container dispensing espresso martinis, a brick of Café Bustelo, and bags of pink popcorn. In many ways, this made a poetry book launch less intimidating, taking away the stuffiness often associated with the literary and art worlds. During both events, importantly, no cameras were focused on the artist or attendees: “I don’t maintain any documentation,” she explains. “I’ve lost a lot of my belongings over the years, so it’s very much a part of my work to not maintain my own archive.” The lack of cameras also enables people to let their guards down; a certain feeling that necessitates social performativity is alleviated.

By combining so many references and forms of expression, Claflin’s practice eschews any singular cultural or intellectual context, making it impossible to tie it down to any particular artistic trend or movement. Instead, the artist relies on a certain feeling—one that is intended to create a sense of openness and a sense of belonging; one that avoids all overly formal and rigid ways of appreciating art.

Lara Arafeh is a Brooklyn-based independent curator and researcher and the director of the NY Cultural Majlis. Her focus is on contemporary art with an emphasis on decolonial methodology. Lara is a graduate of Central Saint Martins and received her master’s degree from Sotheby’s Institute London.

Banner image: Whitney Claflin, “Pop,” 2020. Oil, ink, paper, carbon transfer, enamel on linen. 19 1/10 x 16 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Derosia, New York. Photograph by Simon Vogel.