Tributary Ministries: Indira Allegra in Conversation with Allie Tepper

Chaos and grief consume and unmoor. They leave us unsettled—and can often throw us off-course. In this wide-ranging interview, artist Indira Allegra speaks to curator Allie Tepper about how the orientation strategies of a somatic-based practice can ground the self and provide a path toward liberation. Mirroring the peripatetic trajectory of a river, with its many branches and tributaries, the conversation traverses Allegra’s practice in writing, weaving, theology, and historical research to center the potential of healing within the constraints of our built and natural environments.

— Lumi Tan, 2025 EIR

Allie Tepper: Indira, I’m so excited and grateful to be in conversation with you, and to continue the lines of thought that we started a few weeks ago as we walked along the Hudson/Muhheakantuk (Lenape) in Harlem, on Riverside Drive. I got my steps in that day! I’m going to tap into that feeling of motion as I pen these questions, hoping we might weave together a conversation around topics that feel alive to us both, and that are embedded in your artistic practice, including choreography, text/iles, religion, illness, and the liberatory potentials of specific sites.

We began our walk near Union Theological Seminary, the place that brought you to New York, where you are currently enrolled in a Master of Religion with a focus on Buddhism and Interreligious Studies. I thought we could start there, in the surrounds of Union. Could you speak about your decision to embark on this path of study?

Indira Allegra: Yes, in the interest of site-specific writing, we can start at Union. I’ll begin with Karl Barth, one of the most widely read theologians of the twentieth century, who led a movement in Germany that resisted the Third Reich. Barth famously described theology as an orientation device. So here we are suddenly, in speaking about orientation strategies, already in the realm of choreography, text, site, and somatic experience. What do people use religion or spirituality to orient themselves around? Creation. Inner life. Loss. Haunting. Life transitions, both joyous and painful. Remembrance. Death, and what comes through this. All are areas of interest in my artistic work.

My arrival at seminary orients me to the origin point of art itself: we are all looking for meaning. The ability to find meaning in our life experiences and environments, during moments of rupture, is a freedom practice. Buddhist teachings offer me a way to look directly at suffering or taboo in my own experience and of those around me, and be very present with what is happening. Because I’m “checked in” rather than “checked out,” I’m more available to creative potentials woven into the fabric of every moment.

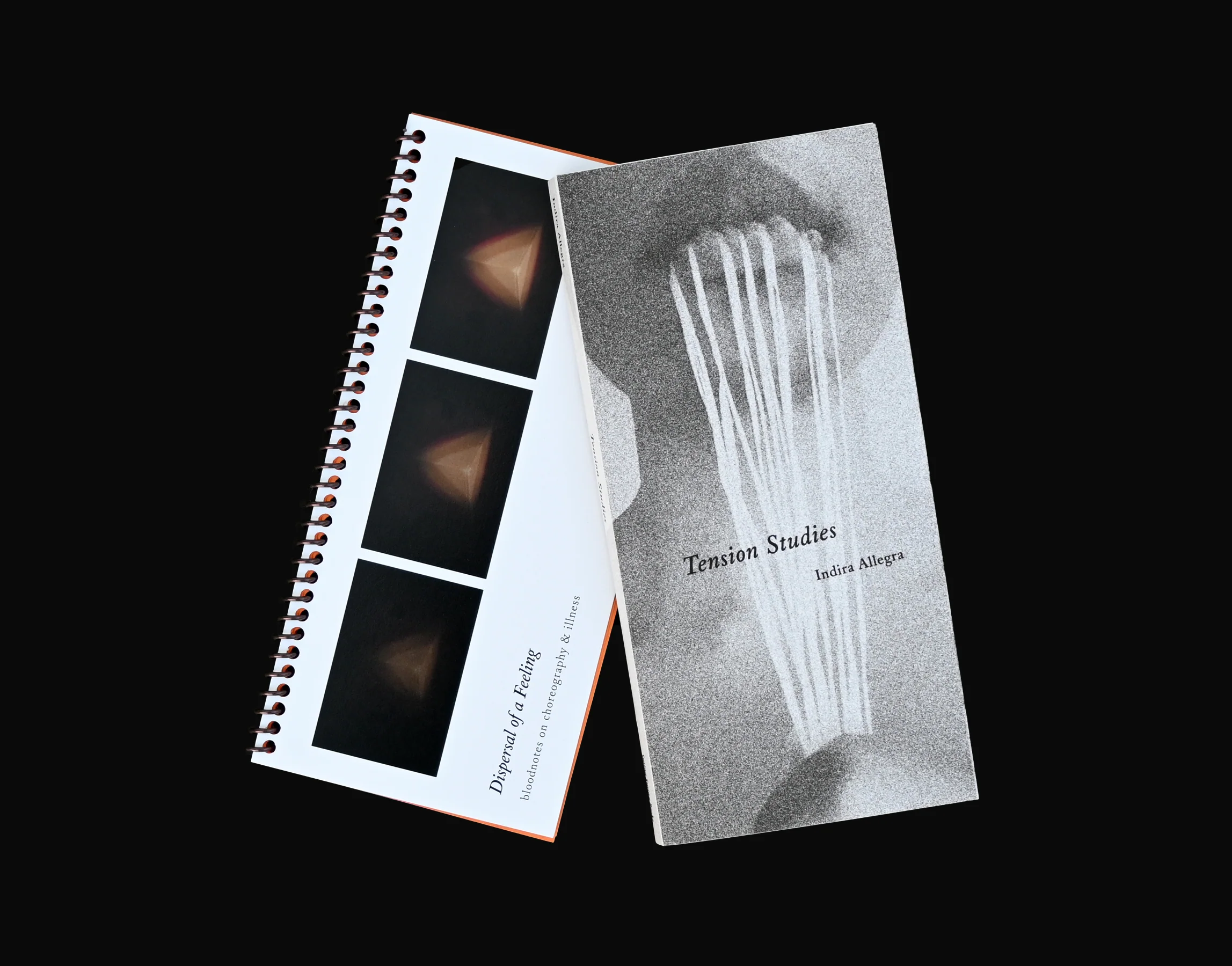

Beautiful, thank you for that orientation to the prismatic uses of theology. Diving in, your book Tension Studies, recently published by Sming Sming Books, offers an intimate window into the many tendrils of your work—as an artist, former sex worker, and domestic violence counselor—grounded in the somatic practice of weaving, where desire lines are drawn. The act of writing here is related to work on the loom. Weaving, you tell us, is a textual practice that precedes the pen. Interspersed between the pages are images of BODYWARP, a series of partner dances between you and your floor loom, which animately responds to your touch. Where does your interest in weaving, in this expanded sense, come from? And did you find pleasure writing this book?

Oh, that’s a superb question. Did I find pleasure in writing the book? Actually, no. [Laughs.] Tension Studies is pulling threads from so many chapters of my life that I feel grateful to break from now. Thank you for seeing the partner dances throughout. The first time I ever saw a floor loom, I was terrified and also deeply intrigued. It seemed like such a kinky, archaic device. Like really? I’m supposed to sit on a wooden bench and engage in repetitive motion with this thing that is totally at the scale of my own body, and no one else finds this … intimate, to say the least? I immediately realized that the loom was a writing device. The weft threads were like stanzas in a poem, and the warp held the tension you need to tell any compelling story. I could have become increasingly technical in my training, but I felt compelled to come back to my somatic experiences with the loom. There’s so much focus on material objects, but if the loom and I could dare to dream outside of those constraints, what might be possible? This is the same as taking one’s meditation practice off the cushion and into the world. When I think about what I can offer this field, it is the ability to take all that patience required to sit down and weave, all that facility working with tension, all that faith in process—because you can’t see the whole until it is done—and make tapestries of tensions that are part of everyday life.

Tension suggests tautness: the interlocking of warp and weft that makes a blanket and soothes, connecting otherwise separate threads. But the word also has connotations of strain and distress—tension in a relationship, unsettled energy in a room, tension in the body. The poetics of this term are so potent in your work. Could you speak a bit about this in relation to the way your practice tenderly addresses grief, and what is difficult?

Tension is inexhaustible because suffering is always a part of life. That’s the first noble truth in Buddhism: that suffering—or dissatisfaction—is part of any embodied experience. Behind a cozy blanket or beautifully handcrafted garment might be exploited workers or deeply polluted landscapes. Seeing things clearly requires looking directly at what was sacrificed, harmed, or hidden, in order for you to have the experience you are having. I address grief so I can live freely. People who cannot tenderly grieve the losses in their own lives cannot be reliable supports for anyone else. If you cannot be a reliable support, then trust is much harder to sustain. If I could not establish trust with sites and the beings who live in and around them—curators, foundations, art handlers, and so on—I would not be able to do transformative work. This alchemy, which metabolizes the difficult into possibility, is where power lies for me. Imagine how you would move in your life, physically and emotionally, if you had 500% faith in your ability to heal from any hurt. What kind of world would you be willing to try living in? What would you take the risk today to do?

Last year you published Dispersal of a Feeling: Bloodnotes on Choreography and Illness as a companion to Tension Studies. A poetic treatise on choreography, the book describes dance as a way of moving with illness and unseen forces—a form of correspondence. I’m taken by this idea that we can strike up a conversation with what ails us, and the many animacies of our physical body. As you write, even a tumor has its own musicality, which can be listened to and responded to.

My somatic intelligence as a performance artist moves through the outer environment, but also especially, through my interiority. I am attuned to how my body forms nests around different feelings or curiosities, and when energy pathways in my body feel cool in temperature or blocked. When I learned about postmodern dancer Anna Halprin’s famous story of how she discovered her colorectal cancer, I deeply related. While she was drawing a self-portrait, a dark circle emerged in her sketch around her pelvis. Struck by this visual, she went to her doctor and was diagnosed. That was her somatic intelligence at work. I’ve had multiple benign and cancerous tumors in my life, and in each case, I had an intuitive awareness of them that led me to ask for lifesaving imaging.

Vipassana meditation also allows me to observe thoughts, feelings, and physical sensations while suspending judgment. In meditation, I might feel a thick feeling behind or below my heart. I turn to this feeling as a gentle friend. There’s nothing to fix, just this quality of ser con or being with, that artist Cecilia Vicuña talks about in her poetry. I bring this same attention to my site-specific work and collaborations. Think about any transformative relationship you’ve ever been in. You probably allowed hidden aspects of yourself to be witnessed by another. By staying in their unwavering attention, something was able to shift inside of you. This is how chaplaincy works, which I’ve been taking classes about here at Union, and is part of the ethic of care I bring to my projects.

I’d love to hear more about this conversational form of choreography, and the uses of dance in your daily life. Are there particular scores or movement practices that you turn to on sick days? Or any teachings that you might be willing to share?

My movement background includes sports, aerial arts, martial arts, and Katherine Dunham technique. I’m a trained teacher of Raja Yoga. I was also an ASL interpreter, so I have a sensitivity to my body being the text. I started taking Butoh classes five years ago, which resonates with my menopausal body. With Butoh there’s so much curiosity about the more-than-human world. I have a daily practice of working with an element somatically. Let’s say I am drawn to work with the scent of petrichor. I let it fill the whole of my attention. There is only the damp musk of the earth rising into the air and nothing else. This invites me to take a shape internally, then externally, and to move. I work with petrichor until the energy begins to lag and then I shift back into human focus.

A practice I love while in human focus is Twyla Tharp’s “Egg,” which involves getting into a tight fetal position and slowly—inevitably—expanding back into the world again. I do this when I’m feeling ill, deeply fatigued, or seizure-prone, which is more often now, in the aftermath of COVID exposures. I also do this when I feel deep grief. The wisdom is that you can’t hold this static, contracted state for long. Eventually, something has to give. You soften. A toe slips out and the feeling of your immediate environment slips in. You remember you can move when movement felt impossible before. Life is still living.

Another vessel of your practice is Cazimi Studio, a collaborative design studio that works with institutions and communities who want to transform the shape or feeling of their physical environment. Cazimi is an Arabic word meaning “in the heart of the sun,” a planetary alignment associated with cosmic revelations. I’m thinking of your Cazimi self as a kind of energy setter, doula, and architect. A necessary service! One recent Cazimi Studio project is May the Hope of My Heart Be Woven into the Waters (2024), co-commissioned by the Blaffer Art Museum in Houston and KADIST, San Francisco, an installation and performance, which turned a stairwell of the Blaffer into a theremin. At the top of the stairs was a glistening black fountain where visitors made offerings of bamboo reeds and prayers. What was the design process like for this commission?

The work of Cazimi Studio is dear to me because it is challenging. It requires relationship building, and a responsiveness to culture, architecture, history, and the changing climate. For this commission, I spent a year studying the ritual and religious history of staircases, while tracking local events like the beheading of Shahzia Sikander’s sculpture Witness on the University of Houston campus, and the banning of DEI initiatives statewide. There was an urgent need for hope in the hearts of people there who were filled with worry and mourning. I realized that built into the form of the Blaffer’s staircase was an instrument for personal transformation.

In thinking about staircases, I was also thinking of prayer, and prayer has mass. Hope has mass. In this piece, mass is felt when someone picks up a wand to imbue it with their wish. The work of carrying these desires—the spiritual effort of pilgrimage—is demonstrated in the ascent up the staircase, and the public witnessing of it. During the performance, visitors whispered prayers to me, which I danced up the stairs, while keeping the specific content of each secret. Through discreet technology, my movements created music on the staircase, as an audible response to each call.

Materially, the fountain is made of a petroleum product and oyster shell concrete, which have ties to Houston’s oil infrastructure. The copper pipe carries water through homes. The bamboo is not native to the area, but thrives there, and is notoriously resilient under pressure. These materialities do not represent easy local histories, yet I transformed them into something that can beautifully hold the weight of what is on each visitor’s heart. The fountain was designed to provide witness through many religious frameworks. For a Christian, water may call to mind Jesus’s talk of living waters. For a Zen Buddhist, water may represent the changing, impermanent nature of reality. For a Jew, water may invoke mikvah, a ritual bath, or the Red Sea. An Ifá practitioner may think about Oshun’s sweet waters. Someone who is spiritual but not religious, may experience water as symbolic of emotion and memory more generally. One source of information (water) represents a multitude of things, and it is the light of this multitude that fills the stairwell.

Water is a material in another recent Cazimi commission, Freshwater Hymns / Rituals of Becoming (2025), a performance installation grounded in the history and lifeline of Black’s Run, a polluted waterway that runs through Harrisonburg, Virginia. The piece includes weaving looms modified into electronic instruments, and a multi-channel video created with local residents in response to Black’s Run. You and I began our own dialogue walking alongside the Hudson, our conversation guided by the subtle choreography of the river and attunement to its presence, and by your choice to locate us there. Following what you call a “tributary logic,” I feel drawn to ask you: to where and to whom does water take you?

Yes, “Tributary logic” may be another metaphor I start using to describe my practice. It follows the way I think about the movement of historical, narrative, or energetic threads in space. What was so interesting about Black’s Run is the way Harrisonburg has built over it in several places. It threads its way, over, under, and through the city like a weaving—sometimes visible on the surface, sometimes dipping below. Surrendering to the movement of the creek, I leaned into its intelligence. I learned about the neighborhoods it touches and who lives there, and its orientation to larger waterways like the Atlantic.

When I was invited to Harrisonburg, I had no idea I would be making a work with Black’s Run or turning looms into instruments to play out the tension of this humble waterway. I don’t have one aesthetic that I expect to work everywhere. Tributary logic is an ecological design logic that uses materials from an area to build in that area, so that it is sustainable for the planet, supports local economies and artists, and rests on stable ground in the hearts of people who are experiencing the work and will remember its making for years to come.

I want to close with the expansive possibilities of your studio practice by asking about a future project, Sail Through This to That. This public commission comprises a set of sails that connect the lineages and handiwork of two women: Ona Judge, the bondswoman who styled Martha Washington and escaped to freedom from Philadelphia in 1796, and Rem’mie Fells, the Philadelphia trans woman and fashion designer who was killed in 2020. For ArtPhilly 2026, you plan to set the sails in motion, in a journey that retraces Ona and Rem’mie’s paths on the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers. There is bravery and faith required to make work of this scale, flamboyance, and politic, in the public sphere in our present moment. The sails offer a gorgeous vision of remembrance and liberation. Is there anything you would like to share about your research and dreams for this work?

Oh my goodness, thanks for asking. The title of this work is a line from “Blessing the Boats,” a poem by the exquisite Lucille Clifton. So many people have opened their hearts to this project. It started with a bunch of site visits, including one that took me to the place where Rem’mie’s body was found in 2020 at the Schuylkill River. I’ve had so many potent experiences keeping the faith for this project: dinner with Rem’mie’s family and attending her annual memorial block party, kayaking the Schuylkill River, sailing the Delaware, visiting Washington’s house in Philadelphia and estate in Virginia where Ona would have worked, visiting local LGBTQIA+ archives, and learning so very much about sail construction. I’ll be working with a sailmaker in Maine this summer using eighteenth-century techniques that would have been familiar to Ona. I’ll use materials and colors that Rem’mie would have loved to wear to express herself as a trans woman. We’ll sail them along the Delaware, where Ona sailed to get her freedom, and up the Schuylkill to honor Rem’mie.

By weaving together the lives of Rem’mie and Ona through time and space, looking directly at the whole of their lives—both the devastating and resilient aspects—a special thing can happen using Philadelphia as a stage. This project is an orientation toward courageous acts of loving-kindness that affirm how beautiful a world can be, where there is sovereignty and safety for all women and femmes. I see this work, and the work of Cazimi Studio, as a form of social chaplaincy, which offers a quality of nourishing presence and ability to listen into what is unfolding in the careseeker’s experience. My education at Union has made my capacity in this area more vivid. I’m an artist because I believe in the creative, transformative potential of life and am deeply fascinated by the mystery of it. I’ll weave wherever I’m invited. That’s tributary logic for you.

Indira Allegra is a conceptual artist and founder of Cazimi Studio. Allegra’s work has been featured in The Art Newspaper, Artnet, Art Journal, BOMB, e-flux, and Artforum and in exhibitions and performances at the Museum of Arts and Design (New York, NY), Blaffer Art Museum (Houston, TX), KADIST (San Francisco, CA), Center for Craft (Ashville, NC), Museum of the African Diaspora (San Francisco, CA) and SFMOMA (San Francisco, CA), among others. Allegra is the author of Tension Studies (2024), Dispersal of a Feeling: Bloodnotes on Choreography and Illness (2024) and Blackout (2017) (Sming Sming Books). They have been the recipient of numerous awards, including the Burke Prize, United States Artists Fellowship, Creative Capital, Gerbode Choreographer Award, CripTech Metaverse Fellowship, and Art Matters. https://www.indiraallegra.com https://substack.com/@indiraallegra cazimistudio.space

Allie Tepper is an interdisciplinary curator and art historian invested in experimental practices in contemporary art. She is the curator of Las Vegas Ikebana: Maren Hassinger and Senga Nengudi, the first retrospective on the artists’ five-decade exchange, presented at the Cooley Gallery, Reed College and the Columbus Museum of Art at the Pizzuti, and editor of an accompanying monograph. She has curated exhibitions and performances for the Walker Art Center, Whitney Museum of American Art, SculptureCenter, and the Sugar Hill Children’s Museum of Art and Storytelling. Tepper is the co-editor of Side by Side: Collaborative Artistic Practices in the United States, 1960s–80s (Walker Art Center, 2020), and a contributor to BOMB and ASAP/Journal. Previously she was assistant director of Triple Canopy.