Time, Tabled: Ghislaine Leung’s Constitutional Critique

When I received the press release for Ghislaine Leung’s exhibition Balances at Essex Street, I felt a fiery wave of recognition. “Fucking thank you,” I may have exclaimed. The release reads as a letter from the artist to her gallerist, Maxwell Graham, announcing a crisis that had found her unable to produce new work for her upcoming exhibition: I do not wish to drop out from my art, I do not wish to entirely outsource care for my daughter. I wish to do both art and care and in doing so change the terms of identity and labor within our industry. I pumped my fist into the air while I held my squirming one-year-old in the other arm.

This text was a compelling act of refusal, all the more impactful for its insistence on Leung’s “active and empowered choice to be a mother,” and the reminder that it’s nearly impossible to fully accommodate the identities of both mother and artist without extraordinary resources. Leung proposed she make an exhibition centered not on the trauma or abjection of parenting, nor any of its psychological or aesthetic dimensions. Rather, she wanted to make work about the economics of parenting while making public the conditions of her production. “My desire to mask my situation is a disadvantage to the understanding of the work,” she wrote. This wasn’t an apologia, but a hearkening to the languages of structuralist film and institutional critique.

Of course, the ambitions of a forceful press release aren’t always translated into the effectiveness of an exhibition; but in this case, they were. More generally, Leung’s recent practice has centered on the contingencies of art’s context. She works with scores, referencing Fluxus artists’ “event scores” that draw attention to mundane activities (Alison Knowles’s Proposition from 1962 which reads simply “Make a salad,” to take a famous example), to be executed or performed by the gallery. She has dubbed this mode of production “constitutional critique”—or an inquiry into “how we internalize institutions and constitute, in bodily terms, their written and legal industrial design [and] the negotiation of rights.” At Essex Street, the context in question was her own quotidian schedule: one work dictated the terms of all the others. Times (2022) established that, though the exhibition would remain open during regular hours, the physical manifestation of the works on display would only be accessible to the public during the hours the artist is able to spend in the studio: Thursday and Friday from 9am to 4pm.

It must be said that this is a fairly generous block of time by the standards of many artists who are caregivers, especially in expensive cities such as London and New York. Quit complaining about your childcare, one artist—herself a new mother—said, recalling the criticisms that have always been leveled at projects of institutional critique. (Marx wrote The Communist Manifesto at the ritzy La Maison du Cygne, etc. Personally, I can’t find childcare. I wrote this text during the sometimes forty-five minutes and sometimes two hours and often not at all that my son naps, after he goes to bed, and in the car while my husband was driving. I wrote this during those times that I wasn’t already writing for my part-time job. I tried to write it while sitting in my son’s room one afternoon while he played, but he became obsessed by the smooth surface of my laptop, and then the charging cord, and then the electric socket, and then my coffee mug, and then he decided to bang his head repeatedly on the carpet because it got my attention every time.) But—the process of removal by the demarcation of Times introduced a series of propositions that were essential to understanding the exhibition. This work necessitates the presence of the working gallery staff who obscure or take down objects, and if you enter while this is happening, you’ll see a performance of the reproductive labor of the exhibition. The fact that the physical aspects of the works will be reinstalled again and again seems futile, like wiping formula from the floor just as a fresh splatter falls from a highchair.

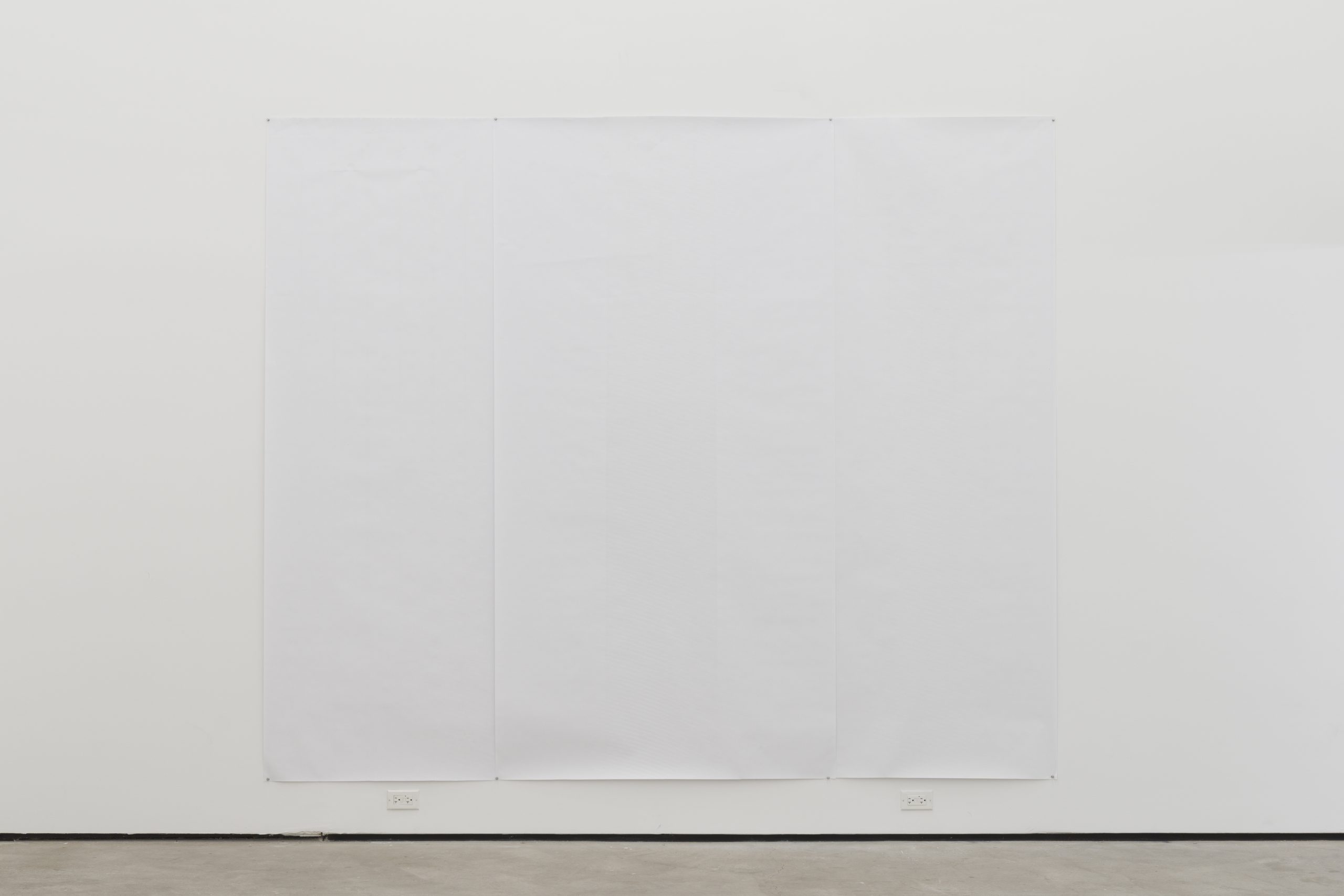

If you managed to make it to the gallery during the artist’s studio hours, you would find a spare installation of works that, depending on your domestic life, may or may not blend into the woodwork. Overall, the works draw attention to the gallery’s capacity, or incapacity, for childproofing. Many of them involve found objects, including Gates (2019), a score for which child safety gates are to be installed on all thresholds of the exhibition space; Monitors (2022), wherein a monitor poised at the gallery entrance plays a live feed channeled from a camera installed in the gallery offices; and Fountains (2022), a water fountain intended to cancel sound. The various installations of child safety gates create their own potential choreography and constraints for the viewer, but the gates are left open. These readymades, rather than commenting on commodification or appropriation, become a punk statement about lost time and obligation. As if saying, I don’t have time to produce something by hand, and my point doesn’t necessitate that I do.

While any immediately signifying aspect of these works is removed from view during the exhibition’s “off” hours, the objects aren’t entirely deinstalled. Traces subsist: the mounting hardware for Gates, the extension cords for Fountains. For the viewer who arrives at 4:05pm, these residues are indications that the artworks are frustratingly just out of view. For the working artist caregiver, who seeks to perform domestic, paid, and creative labor, one context never fully occludes another. The durations of these performances overlap, such that the art is almost always just out of reach, taunting. Present and yet inaccessible.

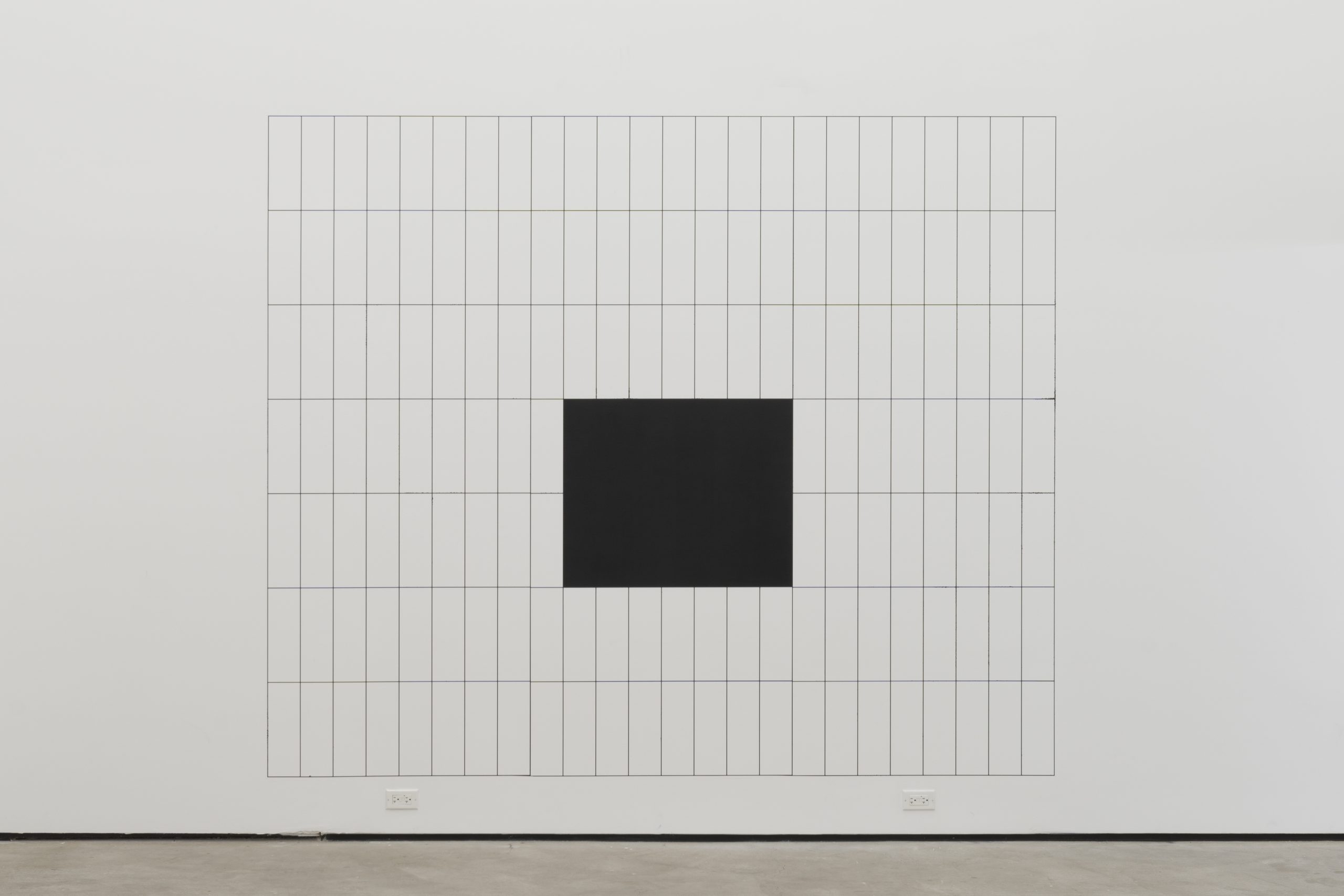

Anyone who is a caregiver can tell you that, once you’ve been entrusted with another human, the notion of undifferentiated time becomes a complete fantasy. And for that reason, the dominant work in the show, Hours (2022), struck me as deeply aspirational. Hours is a wall painting of a neat grid whose dimensions match the wall of the artist’s home studio, divided into the 168 hours of the week. Fourteen of those units are blacked out to represent the hours the artist is able to spend in the studio. The solid, matte black rectangle that results creates a void, a protected nothing, in the center of a busy graphic. If we read the work as the artist intended, this motif of modernism represents singularly dedicated time. The borders are surgical. It’s as if the black shape were that space within oneself where one’s former subjectivity (the before-children self) is waiting, unscathed, undivided. Or maybe the black square is a metonym for the subject of modernism—the white independent (read, no-dependents) man whom we have been trained to conceptualize as the universal subject. But this wall painting isn’t impartial or universal; it’s prosaic, informational, and specific. Maybe, Leung has appropriated the aesthetic of minimalism to blow out its rarified air, to render it with a contingency that extends beyond the phenomenological to the social.

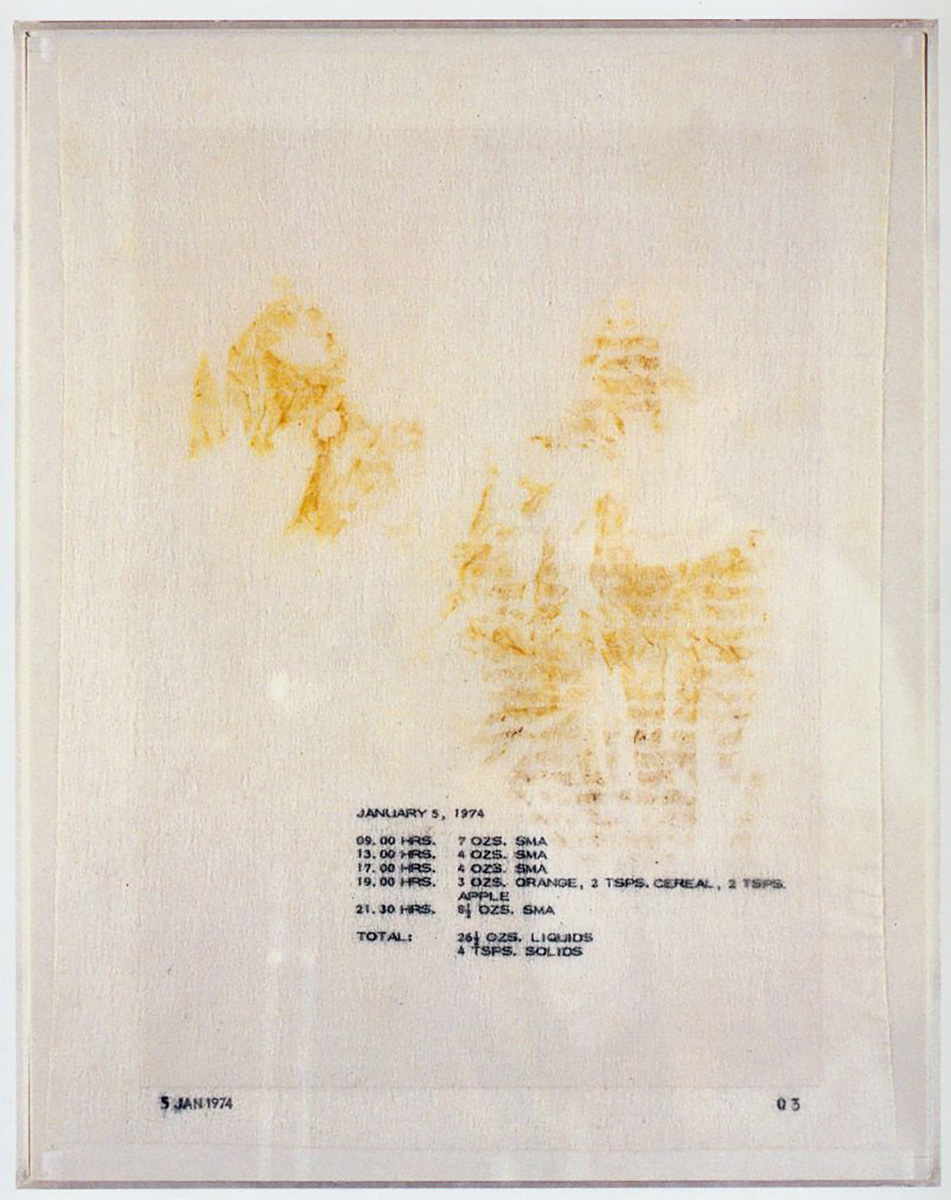

It occurs to me that since mid-century, artists who address parenthood tend to trend toward one of two extremes that might be summed up by Mary Kelly’s Post-Partum Document (1973–79) and Anne Truitt’s 1982 journal Daybook. Where Kelly made conceptual work exposing the messiness of diapers and transitional objects, Truitt made minimalist sculptures that are void of any trace of the context that pervaded her domestic life, while her writing is consumed by its struggles. A few more nuanced examples come to mind. For example, Blondell Cummings’s 1981 dance Chicken Soup, a solo work in which the performer moves through a series of gestures appropriated from domestic labor, frantic, fluid, adaptable, and joyful. Or Barbara T. Smith’s 1965 photocopy works, for which she leased a copy machine and installed it in her dining room, where she documented the labor and effects of housekeeping and motherhood while experimenting with the new technology.

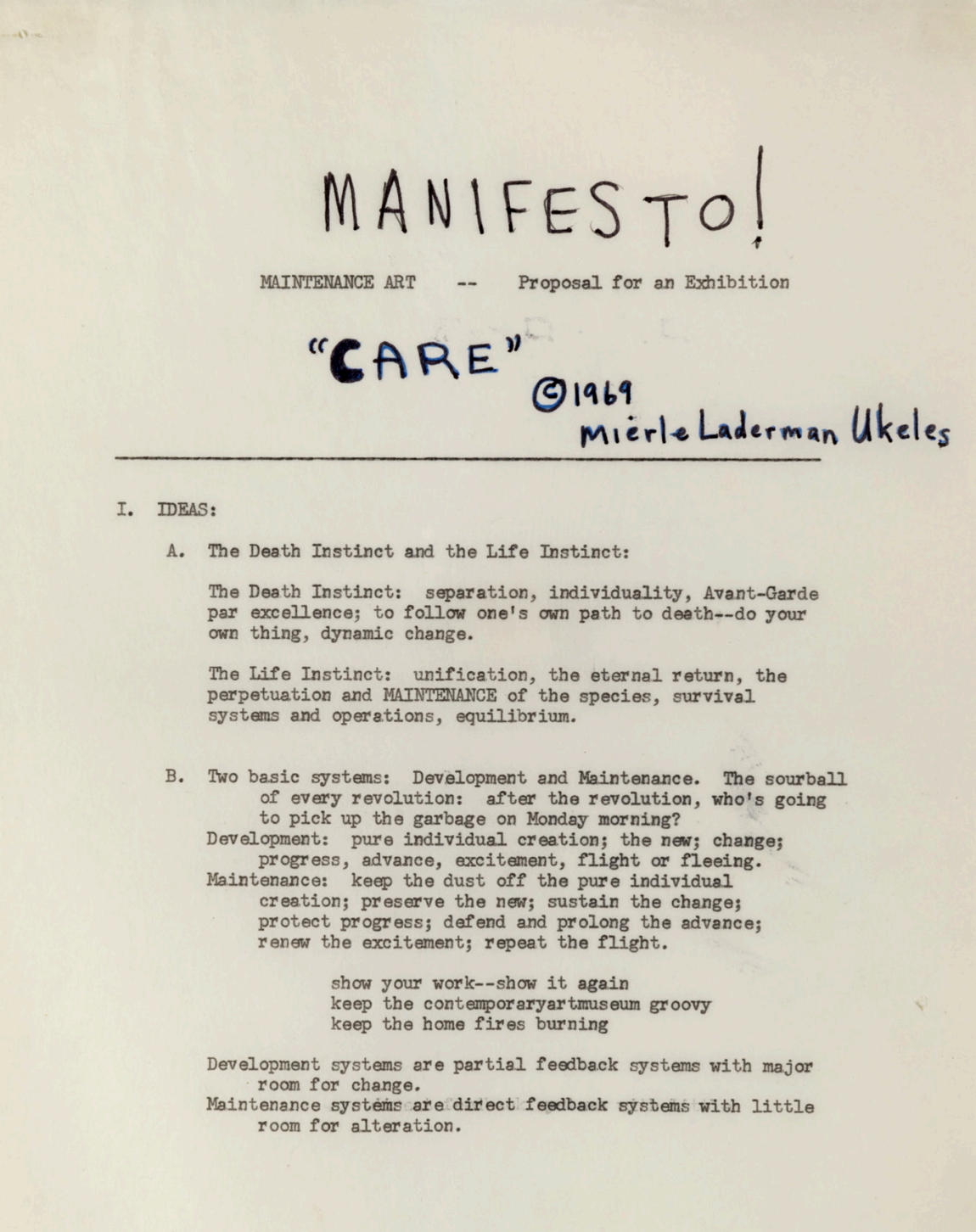

The materfamilias of Leung’s exhibition, though, is Mierle Laderman Ukeles, whose 1969 “Manifesto for Maintenance Art” looms large over Balances. In her satisfyingly brash dictum, Ukeles summoned Duchamp to nominate the oft-unrecognized act of reproductive labor as art. I am an artist. I am a woman. I am a wife. I am a mother (random order). I do a hell of a lot of washing, cleaning, cooking, renewing, supporting, preserving, etc. Also, (up to now separately) I “do” Art. Ukeles identified that the infrastructures of art have privileged development, or “pure individual creation; the new; change;” over the endless work of preserving, sustaining, repairing, cleaning, and maintaining the products of and conditions for change. While Leung doesn’t claim her reproductive labor itself as art, she channels Ukeles’s spirit in insisting that the economics of mothering, or parenting, or caregiving, are essential to engage in the context of arts discourse, worthy of aesthetic and conceptual examination.

Though the heart of Leung’s exhibition lies in the turns of the works’ appearance and disappearance, the show isn’t about visibility, exactly. It’s telling that the least successful work therein is the titular Balances (2022), a scale placed directly on the floor. The work reads as a metonym for the artist, too neatly literalizing the ideas in the show: the times that the work is not in view coincide with the times the artist has no work-life balance. Metaphors for the struggle of caregiving miss the point. Yes, with this project Leung draws attention to the sheer impossibility of doing it all, balancing conflicting durations and demands, integrating seemingly incommensurable identities. But the thing is, the terms and critiques of the show are already well understood. I always feel confused by a recurring acknowledgment that those inequities that are most obvious are likewise often the least articulated, especially in the sacred space of art. Confused, often, by my own acceptance and ho hum—but honestly who can see the forest for the trees when a toddler has discovered a way to free himself, in the thirty seconds it takes to retrieve a hardboiled egg, from the harness of his highchair and begun to hurl himself, sideways, like a breaching whale, from his seat. That a struggle so foundational to a vast portion of the population as to be rendered invisible was treated with urgency here, well, seemed novel. I felt proud of Leung for refusing to be excluded from her slated exhibition due to her domestic choices and obligations, for being clear-sighted enough to state the obvious.

Annie Godfrey Larmon is a writer and editor based in Garrison, New York. Her writing has appeared in such publications as apricota, Artforum, BBC Culture, Bookforum, CURA., Even, Frieze, MAY, the Miami Rail, Spike, Texte zur Kunst, Topical Cream, Vdrome, WdW Review, and The White Review. She is currently at work on her first novel.

Banner image: Installation view of Ghislaine Leung, Balances, Maxwell Graham/Essex Street, New York, 2022. Courtesy of the artist and Maxwell Graham/Essex Street, New York.