The Wanda Coleman Songbook: Cauleen Smith in Conversation with Lynn Hershman Leeson

On the heels of her recently closed exhibition, The Wanda Coleman Songbook at 52 Walker, artist Cauleen Smith spoke with her former professor, renowned video artist Lynn Hershman Leeson, about topics such as Blues limericks, Los Angeles versus San Francisco, and Smith’s profound connection to Coleman’s poetry. Additionally, they delved into the impact of living in L.A. on their creative processes and the challenges of navigating the art world’s expectations, as well as gaining recognition after years of grinding it out in the art world.

Lynn Hersman Leeson: You’ve done such an incredible job of translating Wanda Coleman’s poetry into a cinematic landscape. I’d love to hear more about how you first came into contact with Coleman’s work: do you have a strong memory of a single moment, or was it something that you got to know more deeply over time?

Cauleen Smith: I feel like I’ve known about her poems forever because I grew up in California: she’s such a West Coast kind of literary presence. But it was only when I moved back to L.A. after being away for seventeen years that I really started to delve into her work. I was trying to get reacquainted with the city and needed some kind of orientation. I read Mike Davis’s City of Courts. Someone pointed me toward Wanda and I was like, “Wow, this is really it.” It’s crazy that she wrote most of this stuff in the ’80s. It still really resonates with me. And not only that, but I also feel like it was a voice that you don’t really get to hear: it’s so unfiltered, hypercritical, very rageful, bolder. These are not the kind of poems you can put on Instagram as cute little affirmational quotes. And I loved that. So I just found myself really returning to her as I was settling in here.

What attracted you to do this project, in particular?

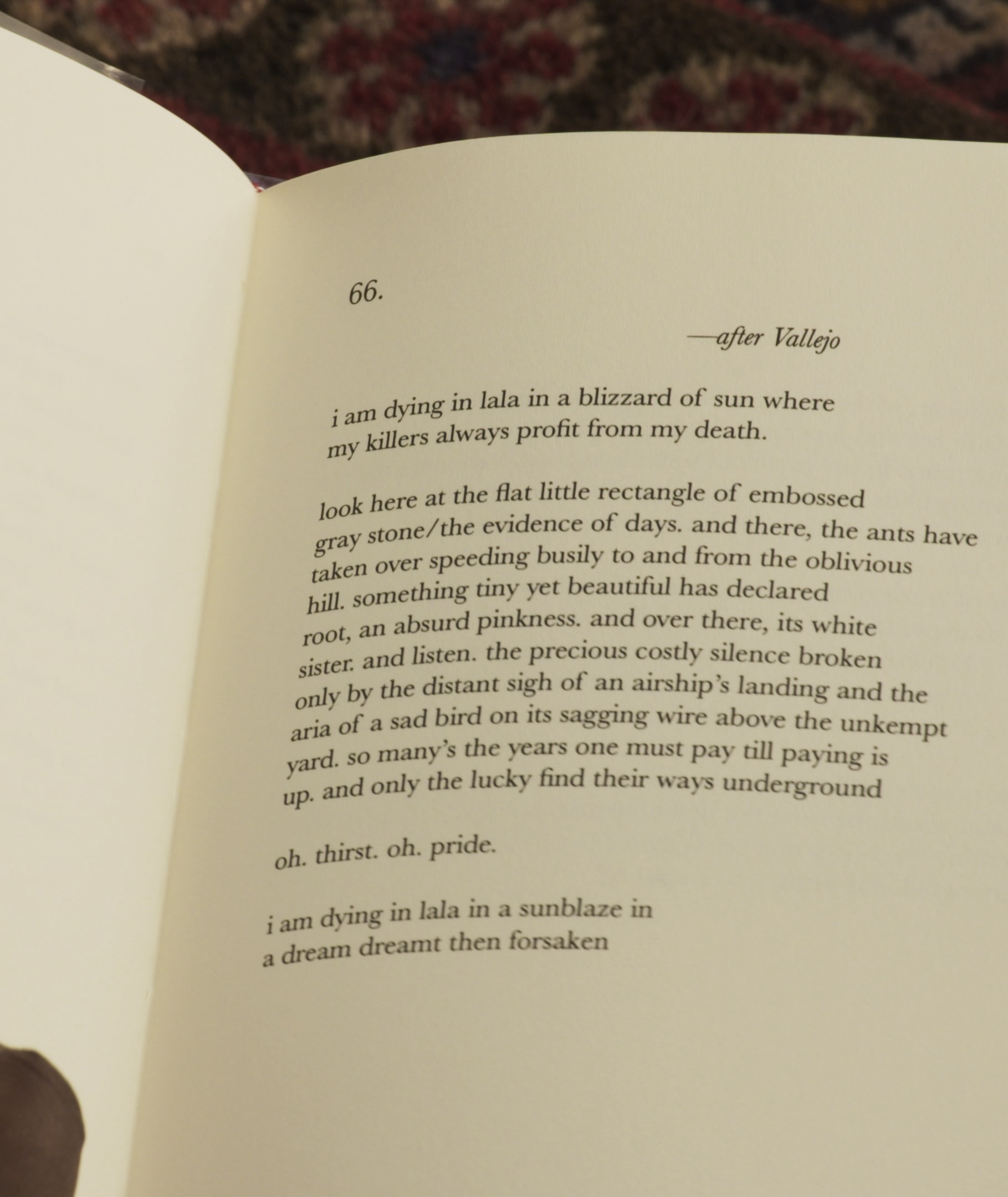

First of all, Black Sparrow Press used to make really beautiful books. So Wanda’s books are beautifully printed, and I just kind of wanted them as objects. So I started looking for them on ThriftBooks and AbeBooks and got as many as I could, just collecting them as beautiful books. And then I was reading them and noticing that she had a tendency, every once in a while, to slip into a Blues limerick. Formally she’s pretty complicated and rhyming is not a thing Wanda does unless she decides it’s the thing she wants to do. When she uses rhyme, it’s almost always in a Blues limerick form. And she uses it very pointedly, very sharply. And I thought, this is so interesting.

She references music, she references Jazz a lot, too. And I wondered if Wanda ever sang or had a band. Some poets like Jane Cortez had a band. Maybe she had a band, though I couldn’t find anything to that. And then I met her brother and he told me that their other brother, Marvin, used to play keyboard. So I found a CD of Wanda recording with him playing behind her, but I didn’t hear any actual music composition, and I just got curious. I realized I would really love to know what other women musicians, in particular, would do with this poetry. I wondered if these poems would be as unsettling for musicians as they are for me. I thought, “Oh, it would be interesting to make a Blues album out of these poems.” So I pulled the poems that had the limericks and I called Ebony L. Haynes to talk about the project. I started calling musicians, but nobody wanted to make a Blues album. It’s not really fashionable, it’s not cool. But everybody was pretty interested in Wanda, so that was really interesting.

Do you think you’ll do anything else with her? About her?

Yes. I don’t know when I’m going to get to it, but I feel like I just scratched the surface with the record.

Wanda worked as an editor of a Black skin magazine called Players Magazine, which was this ’70s Playboy-type magazine. She edited the first six issues. She was just so ambitious with this magazine and had a politically ambitious agenda with it, which was to kind of merge high and low culture, and Black culture and discourse, together. So there would be a film review of Ganja & Hess, an art film, but then there would also be conversations about the politics of living in prison or some kind of working-class employment predicament, all alongside pictures of naked women. This was the ’70s. It was such a naive time. So the pictures now, they’re just very pretty, very sweet.

I have five of the six issues that she edited; I found them on eBay. In the second issue, Wanda put Pam Greer on the cover, but I cannot find that magazine. I’m sure other people have it collected. It’s just not circulating. In one of the issues I do have, the imagery of the women is very glamorous. It’s just a very beautiful kind of photography. But in later issues of the magazine, the women look a lot more debased than they do in Wanda’s issues. I’m really interested in how she wanted to picture Black women for male consumption, how she was shaping the discourse inside the magazine, what that said about Black culture then as opposed to now, and the politics of Black respectability—what Black women should be doing, what we are supposed to care about, and how we’re supposed to be presenting ourselves, versus Wanda’s questions about that.

But you like Los Angeles?

I do. I lived in the Bay Area, too, and everybody up there just hates L.A. and talks terribly about it. But I ended up getting into grad school and moving back here, and I was like, “Wow, this place is so interesting.” It’s so vast and composed of microworlds. I feel like every time I go somewhere, it is an entirely new ecosystem. And there’s literally always something about the city that you don’t know, that you find, and that just really appealed to me, and it still does. The driving and the traffic—I find most cities horrible in that regard. So L.A. is just a little bit more intense. But I mean, I had been living in Chicago, which has appalling traffic, and I’ve just never really lived anywhere that didn’t have terrible traffic. So that kind of thing doesn’t really phase me.

I wonder if you remember this incident when you were in my class and were about to give up, thinking you could never make it. What made you stay, what made you change your mind?

I think I did give up. I didn’t understand art and how it worked or how it was a life or a job. I felt overwhelmed by what I needed to know in order to do it. Your class was really mind-blowing for me because people were bringing in so many histories and theories and legacies of culture that I just didn’t have any knowledge of.

I wouldn’t have used the word at the time, but your class was extremely rigorous. You promoted a very inquisitive, discerning way of looking at art. I still joke with friends that I think you were maybe the first crit I ever had. And I was just like, “What? This is terrible.”

I see this happening with my undergraduate students, too, where I’m digging into their work and they’re just like, “What is happening?” It can be uncomfortable. At that time, I just didn’t think I could do it, and I also couldn’t figure out how to fit into it. The things people were talking about, the things that were important at the time, I just didn’t have a grasp of my own place in that. And it just took a long time.

Yeah, well, it does for everybody. It takes a lifetime and then you can’t use all the things that you’ve learned. Do you think that this is what inspired you to shoot out of your car window?

The irony was that a lot of the footage where it looks like it’s coming out of the car window is actually us moving in between sites. We just turned the camera on while we were traveling; we would go to Griffith Park and then to Santa Monica Beach. Tony, the camera operator would just set up the camera, so we recorded everything. It is literally one of the easiest ways to film. In L.A., we had a lot of issues around watch towers because the woman who runs that park is very proprietary. There are technically laws in L.A. about what kind of film equipment you can have on the sidewalk. But as long as we kept it in the car, we could do whatever we wanted.

Is The Wanda Coleman Soundbook going to go to L.A.?

It is. The Broad Museum bought the installation. It’s incredible. I can’t believe it. They announced it early because they’re building this new building, and they wanted to say what’s going to happen in the new building, and my installation is one of those things.

That’s great.

I’m nervous though, Lynn, because I made it knowing that it was going to show in New York and that it would be in January. I was like, “Oh, I just want New Yorkers to kind of hate their lives!” I just want this warm California sunshine bathing over everybody. And that is what happened. People would come into the gallery and then they took their coats off, you know what I mean? But in L.A., I’m just not sure how it would translate. You get out of your car and go into a building and then you watch film footage of L.A. taken from a car window. There’s a sort of circularity to it; it doesn’t feel like you’re changing environments. I don’t know. We’ll see. It’ll be really interesting to see how it plays.

Yeah, for sure. Maybe in other places, too. Do you see your next piece being an extension of this, or do you have another idea for the next work you’re going to do?

Well, I’m working really hard right now on a film that is sadly not really related to Wanda Coleman at all. It’s more thinking about geological time, about its kind of optimistic, apocalyptic visions: what happens when the world ends, and what we could do after that happens. The aftermath of the end of the world is kind of what this film is about, looked at through the lens of geology.

Where’s that one going to open?

In Oslo at the Ostrip Fernley Museum. Have you ever shown in Oslo?

I’ve shown there, but I haven’t been there. They invited me. I didn’t go.

I’ve really loved watching people finally figure out how important your work is, how prescient it was at the time it was made. After thirty or forty years of making this work, it’s almost like it has finally found the audience it was for.

I agree with that.

I remember in particular that I really loved the Roberta Breitmore character. It blew my mind. You were making that work while you were teaching us, and I was like, “This is crazy.” I couldn’t even understand how it was possible to make something like that. And now, thirty years later, it feels like you built the prototype for how young people actually live. You even revealed the dimensions of that in ways that people were not necessarily prepared to see. And I just find it amazing. So I’m just really happy other people figured that out.

Finally. Yeah. I just had to wait for two generations to be born.

Can I ask you, because I feel a little bit the same way—I feel really fortunate, but I basically made films for twenty years and no one paid any attention. Do you ever get resentful or just kind of think, “screw these people,” or are you just enjoying yourself?

Well, I’m enjoying myself, but I keep thinking, well, what if this had happened twenty years ago? It’d be nice to have not struggled as long as I did. I was seventy-three when I had my first show. The works had never been shown ever.

Jesus.

So some of the pieces were fifty-four years old‚the important pieces, first media works. And it would’ve been nice if I was sixty-three.

Or even forty-three. Wow.

But you just take it. I think that maybe if any kind of success had come earlier, I probably would’ve repeated myself. So this way I was completely free to explore whatever ideas I had because I figured it didn’t make any difference. No one would show or buy them.

This is the part I relate to as well. I feel like now, everyone is watching. Whereas before, I could just make whatever I wanted, and no one cared. And it was amazingly liberating. There’s some works that I made I like ten years ago that I can’t make that way anymore. Very underground. Now, suddenly, there are all these other support mechanisms like a museum or a funding source, and it changes how you make it. That’s something I’ve really been wrestling with lately. I hope it doesn’t sound like I’m complaining. I’m just trying to figure out how to make this kind of work, which is really about exploring questions that I have, when people want the answers before I even make it.

Lynn Hershman Leeson is an artist and filmmaker based in San Francisco.