Temporary Constellations: “Entanglements” at MAMA Projects

In her review of the group show Entanglements at MAMA Projects (on view from June 12–July 31, 2025), Kathy Cho positions herself as an outsider returning to New York City as a site of intimate relationships—romantic, platonic, and professional. An exhibition examining contemporary ideas of the fetish, Entanglements spurs Cho to interrogate why we devote ourselves to and seek pleasure from objects, however fleeting that pleasure might be. For Cho, these ephemeral touch points are formed not only between the artworks and the viewer, but between the push and pull of needs that establish our relationship to an art industry driven by various forms of desire that crystallize into power.

— Lumi Tan, 2025 EIR

It’s an early summer evening and I’m passively staring across the subway platform as sweat simultaneously drips down my chest and back. Under the glaring fluorescent lights, I glance at strangers nearby—some alone, some coupled—and wonder where they’re off to. I’m headed to MAMA Projects in Chelsea to experience the group exhibition Entanglements, which was served to me through my Instagram algorithm while I was wading through the seemingly endless number of exhibitions concurrently open in New York City. Though I relocated to Omaha last year, I have come back to New York once a season: partly to nudge along the ending of a nine-year relationship, but also to spend time with friends in-person and see as much art as I can.

MAMA Projects works with artists on the cusp, both national and international, who do not currently have gallery representation. Entanglements bloomed from ongoing conversations about shared interests between Berto Santana, the gallery’s Founder and Director, and Thais Bignardi Engstrom, a New York-based independent curator. What I encountered was a temporary constellation of artists from all over, defining what desire, belonging, and art as a fetish object meant to them within their own particular lives, as well as relative to one another. When I spoke with Engstrom about the show, she confirmed my impression that the artist’s works could be seen as explorations of the various aspects of desire and fetish, ranging from the erotic to the psychoanalytical, the corporeal to intangible.

While open to the possibilities posed by the artists, I enter the exhibition with my own preconceived notions of what it means to experience a fetish. The etymology of the word holds Latin, Portuguese, and French roots, and implies a “charm, sorcery, allurement, and spell.” The lineage of this term picks up its meanings throughout time in relation to art objects and hints towards the magical or sublime. I think about how difficult it is to explain a feeling or phenomenon, and how it often shifts based on the time or context. Ideally, to define your desires is to follow your intuition on what particular interests feel good and consensual among an overwhelming volume of options. It requires nuance and flexibility, an openness to potential shifts as you begin to understand what you’re seeking. Otherwise, you risk putting the fetish on a metaphorical pedestal, flattening and alienating it by turning it into an illusory or unrealistic fantasy that can feel impossible to satisfy. These conditions are true whether you’re seeking to fulfill your desires in relation to other people, or looking for art that can at once reflect your reality while broadening your perspective.

A long-term research strand of mine considers how artists utilize writing—whether fiction, non-fiction, or poetry—to think through, organize, and expand the ideas behind their practice. This writing can show up directly in the artwork or as a complementary piece (exhibition text, catalog), though sometimes, it is unseen. Artists’ writing often influences how curators understand and write about their work, creating a symbiotic relationship. Engstrom’s exhibition text foregrounds how the associative framework of a group show might help us expand our perspectives on desire by deepening or disorienting our perceptions of how individual works engage with the fetish, as well as related questions about intimacy and belonging. She writes: Entanglements situate the viewer in a visceral voyeuristic state, being confronted back by the object of art and agglutinating two separate existences, becoming one with desire. By embracing blooming fetishes from a spiritual lens, the works on view set the stage for surrendering oneself to interpretations of the arcane attractions in concealed interdependencies.

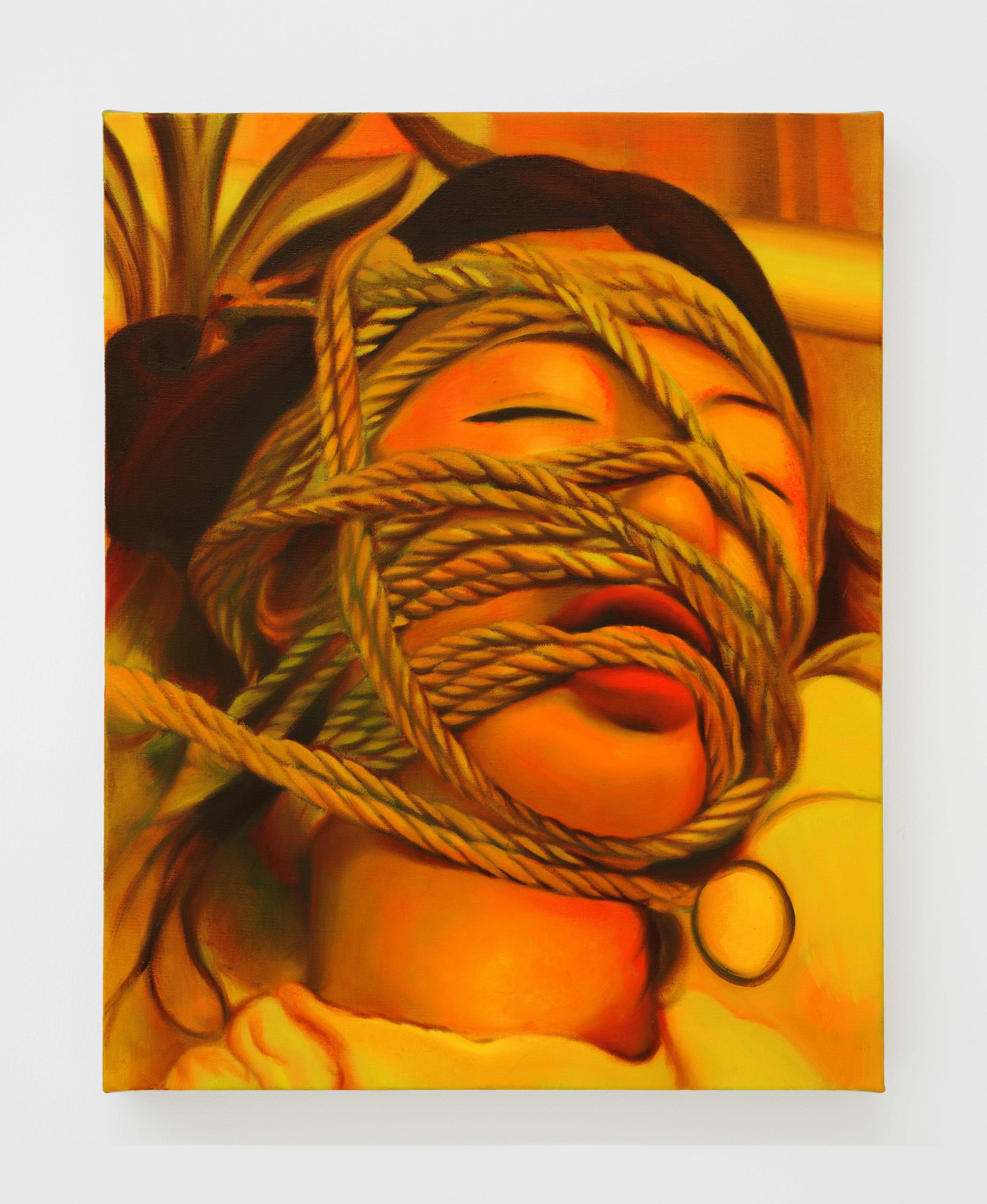

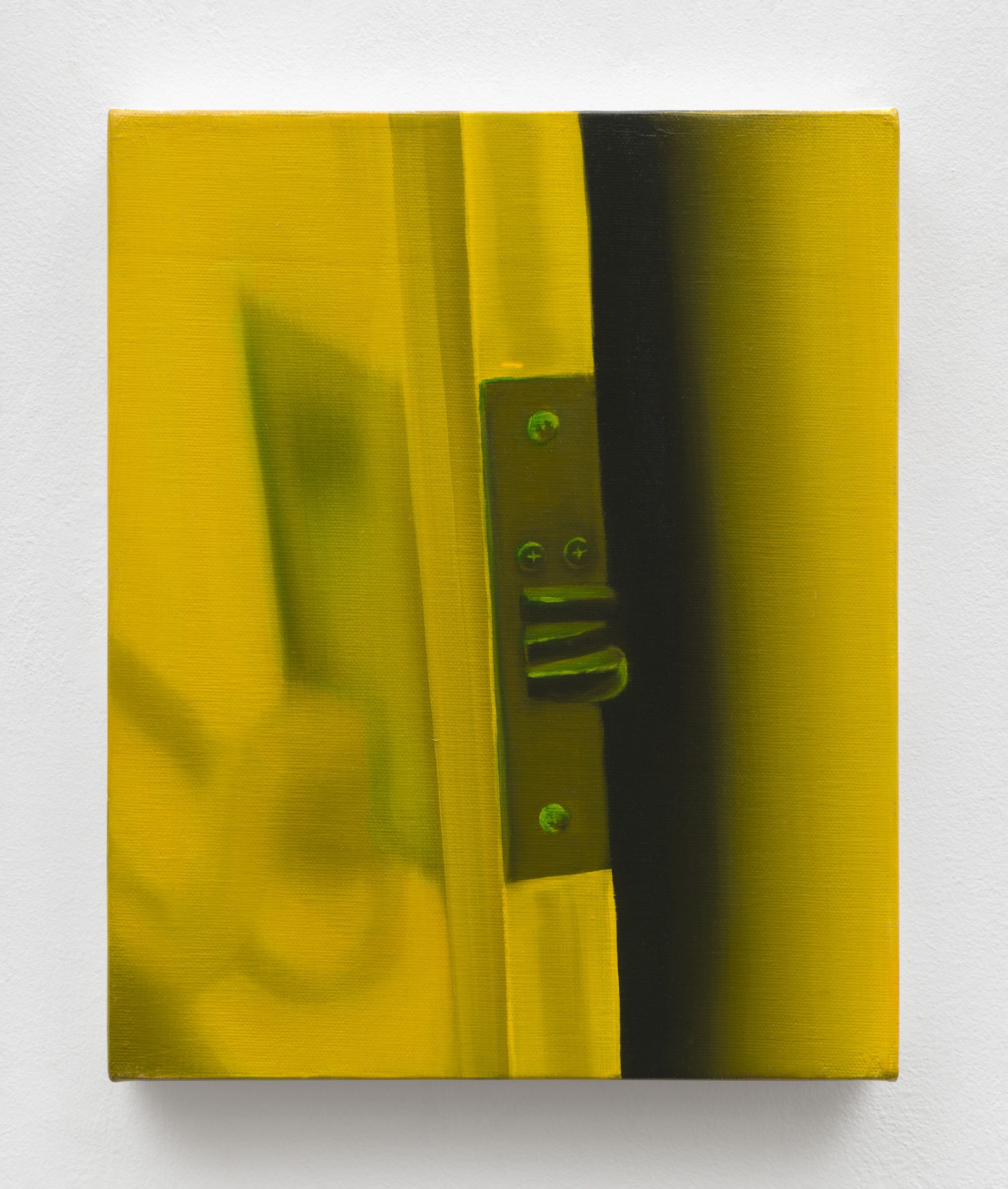

Both Engstrom’s writing and the co-curatorial choices made with Santana in placing each artist’s work actively engage the viewer in longing for entanglements and connections while encountering the fetish art object. Artists balance the use of symbols of erotic fetish and the ready-made with their own choices in editing and placing these components. There are moments throughout Entanglements where the intentional pairing and interplay of different artists provides further depth to each individual work. Tao Siqi’s monochrome representations of recognizable sexual fetishes, specifically BDSM, are one point of reference in this temporary constellation, a fluid entryway to understanding the exhibition’s more immaterial experiences of desire, fetish, and other fluctuating states of being. Paintings such as Strangle and Black Kiss (both 2025) depict faces bound by ropes or stomped by high heels; it is uncomfortably unclear if we’re witnessing a consensual encounter or potential violence. Olivia Drusin’s paintings are similar in size and color to those by Siqi, but absent of humans. Instead, cropped views of architectural moments—hinges, edges, and a slightly ajar door—simultaneously serve as a barrier and an invitation.Though the human body is not present in most of the works in the exhibition, the artworks hint at and coax out the sensations of pleasure and fulfillment that we yearn for from objects and others.

Placed throughout the floorspace of the gallery, sculptures by Cindy Hill and Rosalie Smith are amalgamations of recognizable objects: a horse saddle, bike pedals, fake nails, a dog leash, lamp hardware, fur, and so on. Assembled according to each artist’s sensibility, the sculptures entice and embody a sense of longing, creating mysterious connections and a slightly unearthed lore, leaving me wondering how each component of a sculpture contributes to the whole. Because the chosen objects that make up each assemblage of the sculptures are not straightforward or easily representative of a singular fetish, I instead consider how objects can simultaneously be tools for attaining and objects of our desires.

Using humor and abjection, Smith’s Mx. Snuffleupagus (2025) is a personified nonbinary sculpture that includes everyday objects for construction and domestic labor. It is attached to another Smith sculpture, Towable Radio Comm. Center (2024), by a leash, which has at its rear a dangling BuzzBallz bottle. Mx. Snuffleupagus contains an assortment of traditionally female-oriented objects, with the largest of those objects highlighted in bright yellow and pink, while Towable Radio Comm. Center’s BuzzBallz levies crude sophomoric humor against the seriousness of angular dark wood. Hill’s Bridle fantasy (2023), an unmoving saddle handmade from the leather of a couch, seems to invite the viewer to take a seat. The wordplay between “bridle” and “bridal” layers multiple meanings: using a bridle to restrain; an affect or action that shows hostility or attempts to exert control; or the baggage and utilitarian contract of marriage.

Mechanical sounds lure the viewer to the corners of the gallery, where the silicone tongues in Leandra Espirito Santo’s Inhoim-inhoim-inhoim (2023) sheepishly fail to stab the walls over and over. In Santo’s 360 (2021), a resin hand cycles through a thumbs up, to the middle, then down. Both the tongues and hand are cast from the artist’s own body. The failure of the tongues and the ambiguity of the hand’s stance in these repetitive mechanics mimics the risk of heartbreak we face when we seek out partnership, whether through romantic relationships or friendships. Viewing Santo’s sculptures as they cycle through movements of hope and failure, it can be difficult to parse just where in the pursuit of desire each one is at any given moment. Because I’ve often found myself in relationships that have briefly overlapped in time as I’ve moved from one person to the next, it has also been hard for me to tell where exactly something begins and ends. The ending of a romantic partnership can feel simultaneously like failure and renewal. When I meet up with close friends during my visit, I am surprised by their various admissions that they also want the platonic ideal of life-long monogamous love and partnership. I think of another line from Engstrom’s exhibition text: This unspoken, constant phenomenon of longing epitomizes a collective human loneliness driven by one’s perception of being chronically incomplete.

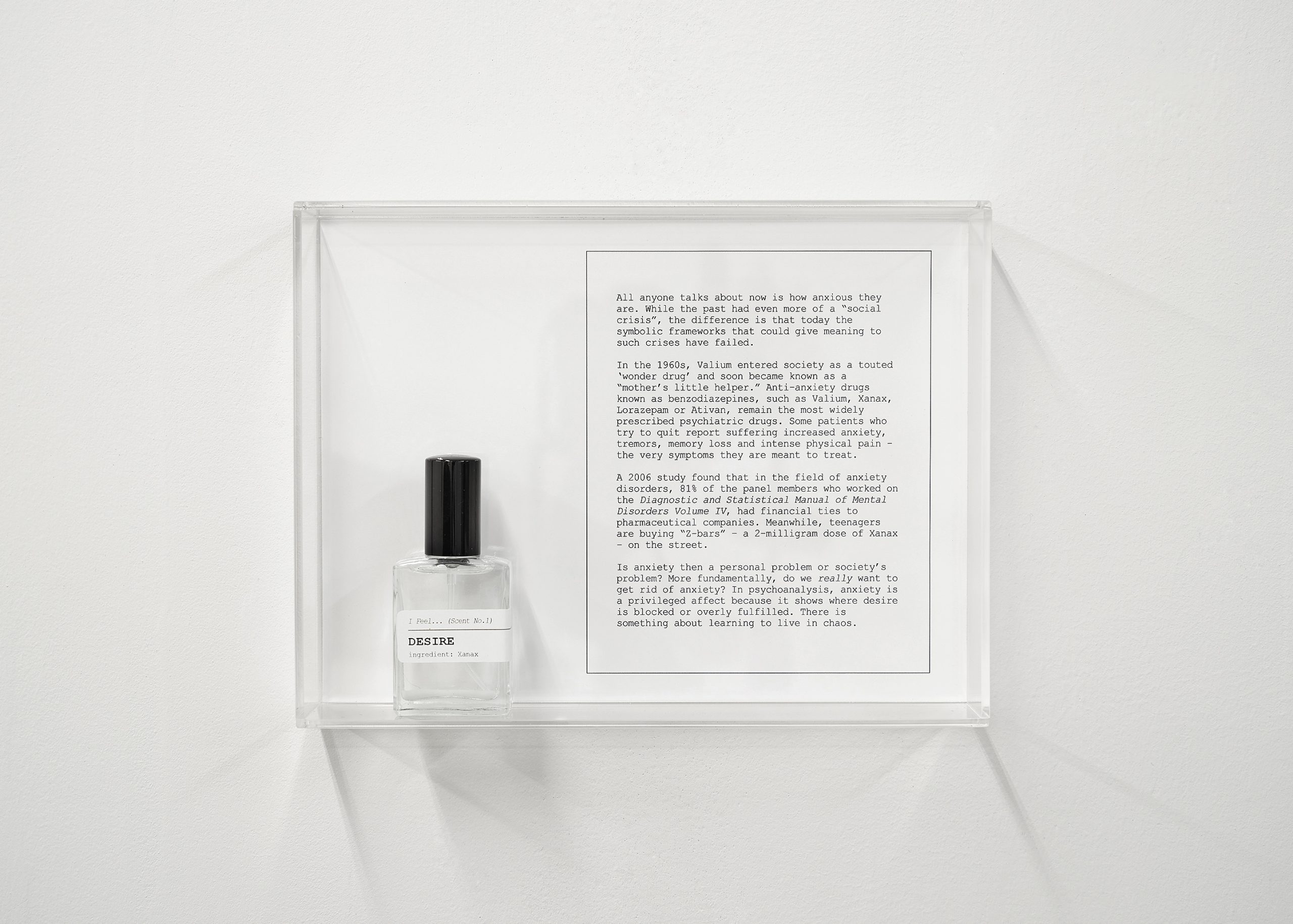

How do we maintain ourselves while seeking out and nurturing our relationships with others? I spend time reading Zorica Čolić’s I Feel… (2025) series of scent-sculpture-displays. Perfumes infused with medications prescribed for anxiety, depression, pain, and erectile dysfunction are placed inside wall-mounted acrylic boxes. Their scents cannot be directly experienced by the viewer, who is instead asked to rely on accompanying text to conjure a scent-image of each fragrance. I am told that the text, which is written by the artist, combines anecdotal experiences with research about the consequences of taking these drugs. Borrowing stylistically from the language of advertisements and individual reviews, Čolić’s text becomes an access point for considering the commodification of healthcare. The transformation of the medication into a fragrance mirrors how medications are often marketed as tools of self-improvement, luxury, and wellness as a lifestyle, instead of being a healthcare necessity.

My visit ends with Čolić’s video Cutaneous Vision (2021–2023), which becomes a neat coda to the temporary constellation of Entanglements. I see actual and artificial body parts, medical replicas and tools, and strange bodily enhancements; many, if not all, are found images. It is difficult to discern if some of these objects are real products for sale online, or AI-generated images of someone’s fantasy. Some clips of bodily enhancements share a visual language with marketing or tutorial videos, reminding me of the way sponsored posts often go unlabeled on social media, blurring the boundary between paid and unpaid content. A rhythmic click of the artists’ unseen joints accompanies each change in image, while a voiceover borrows language from texts on body politics and body manipulation written by Sylvia Federici, Anne Boyer, and Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari. As if speaking to all of the works in the exhibition, it asks who actually holds power in the dynamic between subject and fetish when the object being manipulated and fetishized is one’s own body.

I leave MAMA Projects with initial feelings about how moving within the art ecosystem mimics the obsessive nature and devotion of seeking out pleasure from the fetish object. In a way, I’ve found myself in metaphorical long-distance relationships with multiple art worlds. I pursue art and its communities in every city I visit, and often return to be engaged, stimulated, and reconnected. My willingness to accept short-term opportunities and relocate for work has made me porous and quick to adapt to new places, but it also hinders my ability to settle down. For some, to participate in an exhibition or put oneself out there in search of interpersonal connection is to feel a ceaseless yearning to be seen and belong—only to end up settling for temporary moments of connection. All through life, our existence is unweaved into other peoples, places, things; dripping away particles of us that we unequivocally leave behind. Yet, no matter how thin and far apart the thread of remembrance is stretched, we still feel a form of phantom connection to those lost pieces of us, as if they were still entangled within. Words from Engstrom echo again.

Eventually, I return to Omaha, where I try to come to terms with how my inability to be alone is at odds with the precariousness that comes with my participation in the art world—and am intermittently reminded of how uncanny it is to feel loneliness while in bed with a partner, or at a gathering with friends, or in a city of millions.

Kathy Cho is a curator who supports the practices of living artists by producing exhibitions, events, images, and writing to collectively archive loose narratives of lived experiences. Ongoing research includes expanding the visual and dialogic lexicon of diaspora artists, and exploring the physical and digital architectures of affect. She is currently the Curator-in-Residence at the Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts in Omaha and has previously contributed to art ecosystems in New York, London, Philadelphia, Chicago, and online.