Spirit House at Cantor Arts: A Meditation on Loss and Legacy

How do you define a ghost? Typically we think of ghosts as the spirit of someone who passed away, who returns to haunt the living. What if a ghost is also a family secret that is passed down through generations? Or the memory of someone we only know through photographs and stories?

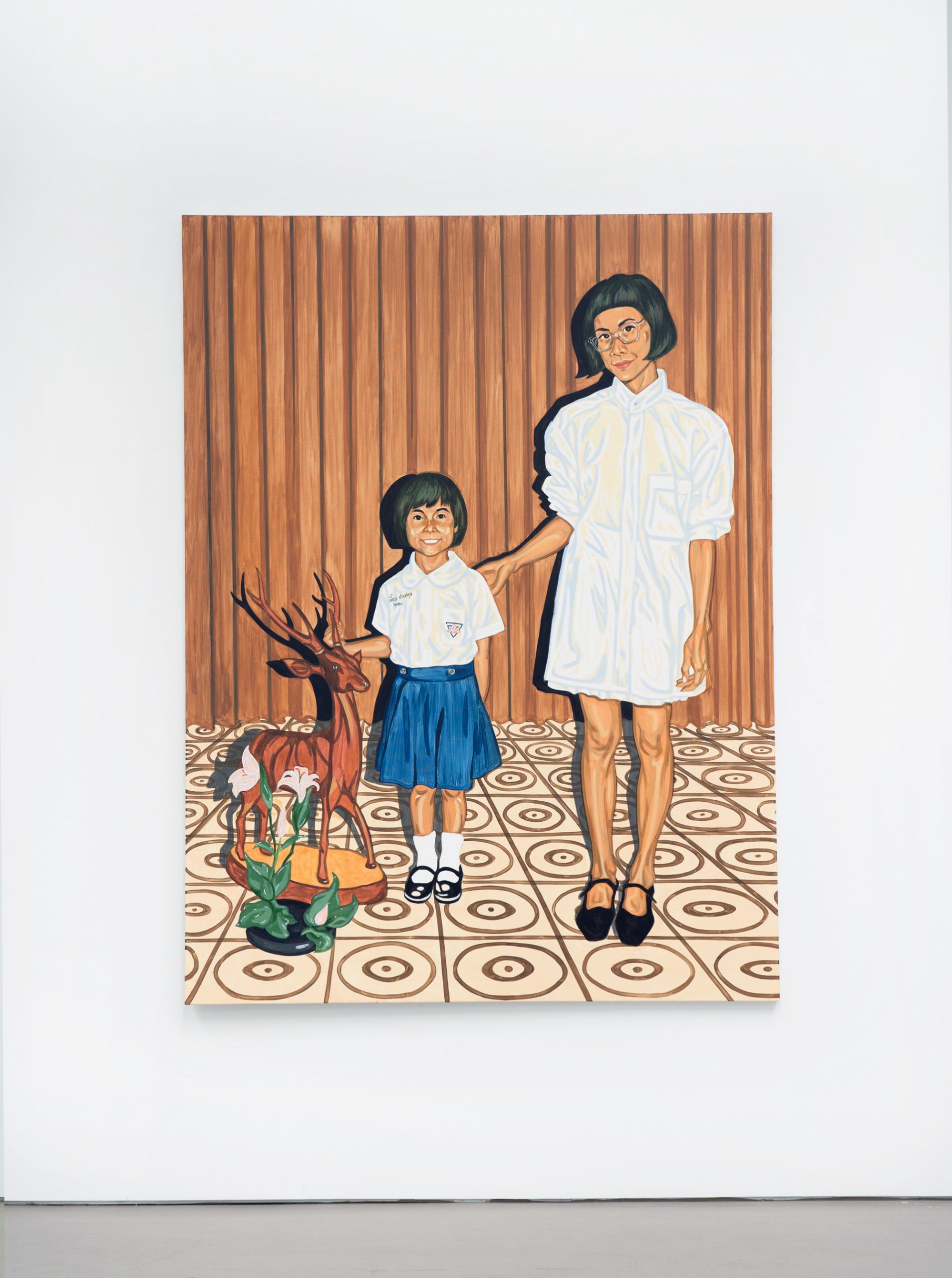

Spirit House, currently on view at the Cantor Arts Center at Stanford University, critically examines personal and cultural concepts of ghosts, death, hauntings, and ancestry, exploring their potential to bridge historical divides through the lens of Asian artists from diverse lineages. As Halloween and harvest season approach, this exhibition offers a timely opportunity to contemplate the intersection of art and the spirit world. This survey exhibition, which includes 34 artists, all predominantly mid-career, practicing all over the globe, offers a multifaceted approach to the role of art in reconciliation with the past. One point of particular interest in this salon is the large role artists’ family histories play in many of the works, often focusing on ancestral spirits, ghosts, and the enduring longing we feel for our departed loved ones and our own past lives.

One of the most profound questions seemingly put forward by the artists in the exhibition is how meditating on ancestral spirits is a fundamental part of the artistic process, as well as an essential burden of human existence. With this in mind, I’d like to point to one of the artists in the exhibition whose work considers this “burden” and its intersection with waking life, which all of us (at least as far as I presently know) inhabit. New York-based artist Catalina Ouyang’s work asks, “What duty do we have to harvest and archive the stories of our ancestors?” I think it’s fair to say this is a question we have all held at one or another time in our subconscious. With the rise of tech companies like 23andMe (also located in Silicon Valley), the true implications of ancestral pasts and how these “ghosts”(A.K.A. family secrets) can haunt us are more a part of the public consciousness than ever. How these stories and past lives, once unearthed, can have unintended consequences for generations is now a common occurrence for many families. The artists in this exhibition not only critically examine this burden of human existence but also the burden of archiving one’s ancestors’ past and how it can weigh heavy on the living, especially when there are family secrets that one might feel are better left hidden in the past. How do we honor our ancestors’ stories while navigating the complexities of their legacies? Spirit House does its best to think deeply about these questions.

Ouyang’s Reliquary Corpus (2021) is a very direct mediation on this question. A genderless distorted wooden figure is adorned with a sort of animal snout, weighted with a long black horse tail, and hung isolated on the flat white gallery wall, giving the feeling of a decomposing crucifix in a Byzantine cathedral. The torso holds a copy of Marguerite Yourcenar’s Memoirs of Hadrian. This historic memoir is a letter from the Roman Emperor Hadrian to his adoptive grandson, Marcus Aurelius, chronicling the complexities of his controversial life, including details about his intense love for the strikingly handsome Antinous, who notably died under mysterious circumstances before the age of twenty under Hadrian’s care and was later, almost suspiciously deified by Hadrian as a God. The book, an eerie tome from an elderly ancestor to his heir apparent, serves as a reminder of how ancestors—complicated figures in history—can influence how we see ourselves, potentially creating a desperate need to improve upon the past, if not to the Roman Empire, then for posterity or one’s own dignity. As these narratives are projected onto our own lives, they inevitably intertwine with our identities, shaping who we are and how we are publicly perceived. I find myself wondering how often an artist’s practice becomes a method of attempting to reconcile, even remedy, this unresolvable condition.

Spirit House was curated by AAAI Co-Director Aleesa Pitchamarn Alexander with Katheryn Cua, curatorial assistant for the AAAI.

Participating artists include: Kelly Akashi, Korakrit Arunanondchai, James Clar, Maia Cruz Palileo, Binh Danh, Dominique Fung, Pao Houa Her, Greg Ito, Tommy Kha, Heesoo Kwon, Timothy Lai, An-My Lê, Dinh Q. Lê, Kang Seung Lee, Tidawhitney Lek, Jarod Lew, Reagan Louie, Cathy Lu, Nina Molloy, Tammy Nguyen, Tuan Andrew Nguyen, Catalina Ouyang, Namita Paul, Amanda Phingbodhipakkiya, Kour Pour, Jiab Prachakul, Stephanie H. Shih, Do Ho Suh, Masami Teraoka, Salman Toor, Lien Truong, Apichatpong Weerasethakul, and Wanxin Zhang.

Lyndsy Welgos is a New York-based artist and the founder of Topical Cream. Welgos is known for her portraits of female-identifying artists, which have been published widely, including in The New York Times, Vanity Fair, Vogue, The New Yorker, among many others.