Senga Nengudi’s emotional residues

Senga Nengudi’s groundbreaking and experimental work is highly embedded in material as well as ethereal realms. Two recent shows in New York put Nengudi’s lesser-known works on view: Dia Beacon focused on her sculptural work, while Sprüth Magers centered photography documenting her interventions into the city in the ’70s and portraits of her husband taken in the ’90s. I invited Claire Voon to write about these two shows in relation to Nengudi’s practice more broadly. In her text, Voon considers the ways in which the entanglement of the personal and the performative has resulted in an oeuvre that engages impermanence in a way that is evocative and transformative.

– Ruba Katrib, 2023 EIR

Standing alone within Wet Night–Early Dawn–Scat Chant–Pilgrim’s Song (1996), Senga Nengudi’s whole-room installation at Dia Beacon, I sensed the work shifting around me. A string of paper, hanging from the ceiling, twirled like a wind chime. Veils of bubble wrap draped over spray-painted canvases fluttered gently, and a massive circle of the crinkly film at the gallery’s center seemed to almost rise and fall. Had this crisp blanket of air recently settled, or was it ready to float away?

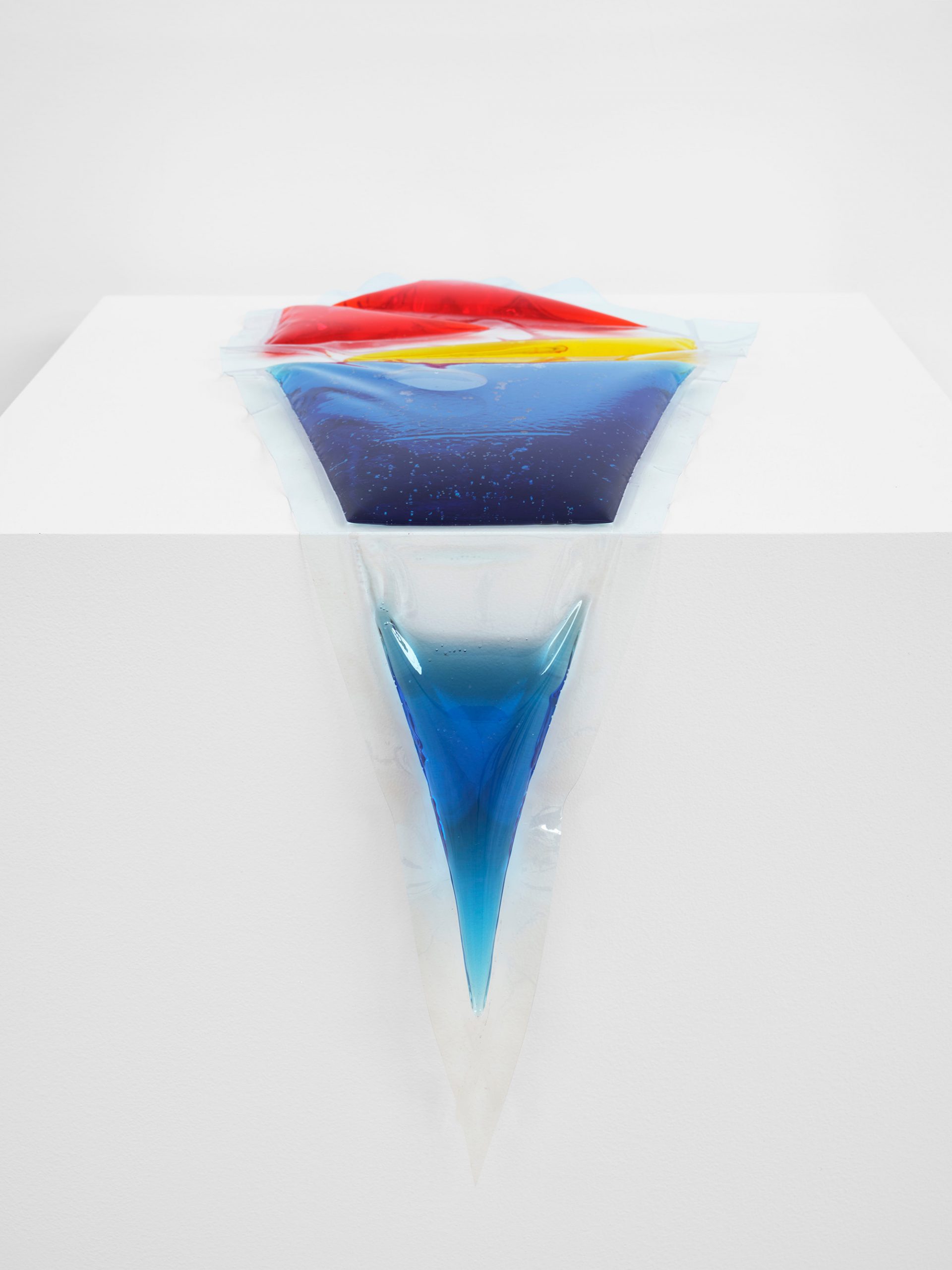

The installation, seemingly roused by the unseen currents from my passing figure, is an immersive exemplar of how Nengudi’s works bring the feel and flow of our bodies into sharp relief. The Dia exhibition, which presents a tight selection of her mixed-media sculptures from the past fifty years, is full of evocations of human movement and mentalities. There are exhalations of pigment, as seen in the hazy puffs of red powder dotting Untitled (2023), a grid of pinned strings extending from floor to ceiling. There are the clear plastic sacks sagging with vividly dyed water that comprise Nengudi’s Water Compositions series from 1969 to 1970. There is the lightness of being that Wet Night embodies and transfers to viewers as we complete a full circuit around the installation of paintings and see colorful, glittering sand at our feet and wispy red figures, daubed on the walls, flitting around us.

Nengudi, recently honored as the Nasher Sculpture Center’s Nasher Prize Laureate, has long been regarded as an alchemist of mundane material. Most famous is her transformation of pantyhose, which she fills with sand and pulls to extremes to suggest bodies stretched thin. I first saw this series, R.S.V.P., firsthand in 2014 at Chicago’s DePaul Art Museum and recall being struck by how directly the flayed, strangely sensual objects express the weight and resilience in womanhood (she began working with the material in 1975 after the birth of her first son). The Dia show doesn’t include R.S.V.P., but rather highlights lesser-known works that make clear Nengudi’s sustained intrigue in the years before and after in the energies of things, and their power to hold our imagination long after we experience them. Her early Water Compositions demonstrate how even plain water, with all its connotations of sustenance, renewal, and healing, can open up a new language of art-making. In Dia’s natural light, works from this series feel remarkably fresh and pertinent, offering a sensuous yet playful counterbalance to the restrained Minimalist and Conceptual works displayed elsewhere.

Perhaps most fun is Water Composition (yellow/green) (1969–60/2018), a quartet of long, heat-sealed vinyl bags plump with yellow- and green-tinted water. Lying in the center of one room, they are as enticing as freezer pops glinting in summer sun; I instantly felt tempted to poke or squeeze them and feel the cool plastic against my skin (as Nengudi originally allowed of her viewers) and watch how these taut pouches might move with my touch. In a corner of the same gallery, Water Composition II (1970/2019) offers a picture of gratified release: a sling of plastic drapes languidly across two lines of knotted rope, weighted by three pools of blue water. Elsewhere, several sacks that taper to a point slump against a wall, stretching out like enervated limbs. These works convey Nengudi’s interest in shape-shifting as related to the body, which over time, moods, and conditions finds varying forms of toughness and vulnerability, tensing to the brink or settling into soft folds. In their purposeful arrest of momentary movement, the compositions, which will shift unseen from nature’s own choreography (the water cycle), also reflect Nengudi’s interest in how the dynamics of dance—more so the emotional intensity and improvisational spirit of Gutai and Noh than the rigidity of Western classical traditions—can coax out a person’s innermost self.

“These works convey Nengudi’s interest in shape-shifting as related to the body, which over time, moods, and conditions finds varying forms of toughness and vulnerability, tensing to the brink or settling into soft folds.”

“I like to dance with the spaces I occupy, creating a triad,” Nengudi writes. “Partnering, we show what each other has to offer.”1 You can almost sense her tiptoeing through Wet Night, where a trail of sand lines the room’s edges, like dusting from an arcane ritual; red-pigment patches amid the grains are further traces of an arc. This specter of a shuffling step (you can hear it in the title, too) bursts into a frolic when you move around Sandmining B (2020), which looks like a parcel of beach during festival season. Dark sand pressed by feet covers the floor. Punctuated by wiggly metal tubes and tidy mounds, adorned by sprinklings of bright pigment, the work is a painter’s canvas as dance composition, with colors splattered on one wall: a final twirl through space. Drawing on Tibetan sand mandalas and Navajo sandpaintings, Nengudi makes healing out of the business of extraction gestured to in the installation’s title. Her spiritual landscape compels us to connect with the transformative possibilities that lie within us all.

Much of Nengudi’s work defies material longevity: sand will be swept up, water will evaporate, pigment will be wiped away. Embracing the ephemeral while expressing resilience—“durable like a bird’s nest,” as she describes—her art is content with its emotional residues. In the early 1970s, the artist installed a different series of sculptures around Harlem, leaving their fates to the whims of weather and residents who may have chanced upon them. Made from nylon, these Spirit Flags (1971–74) were silhouettes of gracefully contorted, larger-than-life figures in various colors, strung up to gently flap in the wind and turn radiant in sunlight. At Spirit Crossing, an ongoing exhibition at Sprüth Magers’s New York gallery, photographs of these transient, lesser-known works—looming in alleyways or across fire escapes—can be seen alongside two recreated Spirit Flags. Intended to capture the “inner souls” of people Nengudi observed in Harlem, the Spirit Flags are in some ways a figurative complement to Water Compositions, also measures of human essence. The flags also anticipate the tensile strength of her R.S.V.P. works, translating the sense of being tugged in all directions.

Still, there is an invigorating energy emanating from these suspended beings. Visitors first meet Holler (1973), a green figure appearing to boundlessly leap through the air, her arms raised like wings and legs springing in opposite directions. In another corner is Twins (circa 1972), a symmetrical black cutout resembling a pair of waving specters. The photographs depict three other Spirit Flags—slinking, lounging, caught in a star pose—offering a glimpse into the experience of encountering them on a stroll. I imagine it would feel like stepping into a new dimension, to turn a corner and snap into awareness of one’s own motions and shape, of the shadows we cast. And perhaps, of the fact we’re never really alone.

“I imagine it would feel like stepping into a new dimension, to turn a corner and snap into awareness of one’s own motions and shape, of the shadows we cast. And perhaps, of the fact we’re never really alone.”

As the exhibition’s title suggests, we’re meant to merely cross paths with these souls. But the momentary can be momentous: I think back to the quiet disturbances coursing through Wet Night or the footprint-like dents of Sandmining B. The phrase also evokes the crossing of spiritual thresholds, a notion palpable in a photographic triptych honoring Nengudi’s late husband, Ellioutt Fittz, who passed away in April. Taken in 2022, the three images depict Ellioutt intimately, reclining in a bathtub with closed eyes, his long locs framing his torso. Nengudi echoes the format of historical altarpieces, with a larger central image in black and white flanked by two smaller color images. The result is a picture of profound rest that evokes both baptism and memorial. And yet, as in the artist’s other series, there is a potent sense of power surging through this stillness, a monumentality overhanging the vulnerability of nakedness. It is her most personal work, and her most direct address of loss, which in her art is entwined always with the indomitability of a person’s spirit.

Claire Voon is a writer and editor who lives in New York.

Banner image: Installation view of Senga Nengudi, Senga Nengudi, Dia Beacon, Beacon, New York, 2023. Courtesy of Dia Beacon. Photograph by Don Stahl.

NOTES

1. Terence Trouillot, “Senga Nengudi’s Lesser-known Writing Practice,” Frieze, June 13, 2023 https://www.frieze.com/article/senga-nengudi-excerpt-236.