Re Modeling

You and I find ourselves in an intimate entanglement. You are at the edge of my fingertips, tapped, right on to the smoothed plastic. My palms resting on the colder steel body: right [write] from the heart, and the mind, thoughts that swim in nascent formless liquidity, quite unvoiced, perhaps not ever precisely voiced, yet finding themselves realized as they meet your eyes, your awareness, your sense and sensibilities. I nod towards my innards, inviting you to peek at my synapses. I guide you through each of my steps. Where have I shown you what to do with me? Or is the premise in my presence and presentation? When were you called here to witness me? Was it at the moment I appeared? Or in so many resounding instances before? And at what moment do I appear? Have I, truly, appeared, or just what you’ll make of me? How do I will you to make of me what you will?

We co-construct so deeply, until you know my thoughts well enough to make them on your own. I’m not sure if you are inside of me or outside of me, because I don’t know if either category is true. What comes first: eros or pathos? Love or demonstration? We merge in an understanding: the most sensual performance, seeing one another, from start to finish, all information brought to bear. We give life to a new idea, and breathe easier in our new world where such togetherness and logic and the pleasure of its aftermath are infinitely possible. I take a giant, two-feet-by-two-feet edition of Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What Do You See by Eric Carle from a walnut toned chest. Crowded around my knees and ankles are twenty-four four-and-five-year-old children. We’re sat in a warmly-lit corner of my classroom. Some smell like orange, pulp splattered, face and hands unwashed from snack. Some smell metallic like sweat. Somebody is a bit unsure of their bladder, and I can smell that too.

This wafting and wading and the walnut wooden chest are not the center of their attention. I am the center of attention. I hug the book and raise my eyebrows; I get myself ready to read, wiggling from side to side on my sit bones, and erecting my spine. I cheat a bit toward them, looking as natural as possible; their eyes meet mine, ready to witness, to listen, to process and co-construct. There is little that feels natural about this particular act of literacy. My readers meet a text face-to-face. In contrast, for this act of the performance, I’ll have to look around the corners of my body. My explicit goal is to perform joyful enlightenment at how a pattern gives way to fluid and rhythmic reading, how they can pick up more words at once and use the picture to identify the changing elements of the text, or ease into it, the semantic symbol decoding via the more directly demonstrative illustrations — despite this cumbersome positioning. Once the class settles into the independent reading portion of our reading workshop, I’ll take out a book at my reading level and model an anatomically accurate reading posture. But for now, I take a deep breath, frame my face with the arch between my thumb and index finger meeting my mandible and temple; I make a soft and deep and thoughtful croon. “Hmmmm.”

I model reading: the how-to technicalities broken down into 180 days of discrete actions, like how to use our eyes to notice everything about an illustration, moving all around the page to interpret illustrations to support comprehension and anticipate text, or how to recognize a pattern with our eyes and ears to gain fluidity and speed, or how to identify easy sight words (words that cannot be decoded) to string together sentences, shaping our mouths into beginning, and then ending sounds, accounting for vowels and vowel patterns, feeling the sensation of fluency as the simple pattern becomes a favorite poem, the allure of the repetition and rhythm, as I dance to the beat of my songlike delivery. I model that reading is viable, inviting, and fun.

Later in the day, I’ll pluck out James Marshall’s version of “The Three Little Pigs,” a (normal size) text I don’t expect them to read independently, word-by-word. I’ll pause on each page, thinking aloud before attending to the words:

“I notice that the mom pig is crying. She looks sad and she has a tissue underneath her eyes. One pig has his eyes closed as he leaves the house; I think this means he is very relaxed, but also— maybe—he doesn’t pay very close attention to things.”

I gradually increase my speed, manifestly confident as I make my way across the image.

“I notice one pig has very colorful pants on, so I think maybe he is an artist and, hmmmm … What do you think about this pig? In the suit?” I urge them towards excitement to draw their own (scaffolded) conclusions.

“Turn and talk to your reading buddy—what do you think?!” They break into excited chatter. I crane my ear downward from my perch to listen to their ideas, nodding my head furiously. I scratch my chin as they piece together the visual cues. I hear some strong deductions and respond with a post-nasal sing-song “mmmmmm,” squinting my eyes as though I hadn’t considered that point before. I count down from five to quiet the duets and call attention to one student: “Jorge, you made a guess that made a lot of sense to me—could you share it with the group?”

“He has a job and he’s got a lot of money,” Jorge says.

I look around the room checking for accord. “And why do you think that is?”

“He’s wearing a tie and he has a briefcase. He looks fancy,” he responds. I raise my eyes and nod. I take a moment in silence as I process and integrate that new thought.

“You know, I think I see people who dress like that, downtown in those tall glass buildings,” I say, pointing toward Downtown Los Angeles from our Pico Union classroom, one “blue sign” town over, to the northwest. “Have you all seen people who dress like that?” I introduce class consciousness. “Liliana, I overheard you use a word that we talk a lot about when we’re making our class expectations.”

“He’s re-spon-si-ble,” she says, belaboring each syllable of the word.

I press my lips down into my processing frown, and stare out of the upper corners of my eyes, nodding quietly. “Hmmmm.” Inconclusive.

“I notice Jorge made some guesses about what the man has and what he does by noticing details about his outfit. And maybe that reminded us that we’ve seen these sorts of clothes in real life. We made a connection there. Liliana made decisions about what sort of pig he is, about his personality, about his character. Super interesting how you each approached that,” I say, low in my throat, narrating the noteworthy replicable behaviors. “Let’s read on to see.” We’ll have to read on to test and confirm these hypotheses.

“I ask questions that are impossible to answer, but answers aren’t as important as the habit of doubt. They’ll begin to extend their empathy in unanticipated ways; they’ll begin to integrate other fields of information, and they’ll begin to doubt their archetypal assumptions: they’ll begin to think critically.”

I’ll spend two years with this cohort, and we will read “The Three Little Pigs,” the version by Marshall, tens of times, and also other versions by other storytellers. By the wintertime of first grade, we’ll uncover deeper and more complicated layers. I’ll test their capacity to redeem the Big Bad Wolf: “What if the wolf needs to get big and strong to take care of his own wolf babies?”

I’ll wonder aloud about the vengeful trickery of the supposedly responsible last living pig: “This seems kind of mean. Did he need to play tricks on the wolf? And how does that keep him safer?”

I give maximal sass as I challenge the author’s implied hegemony of good and bad, scrunching up the side of my nose and holding out my hand. We’ll co-consider the need for animals to build appropriate habitats to stay safe. After we learn about food chains, we’ll revisit the text, and I’ll then pause and incorporate new biology learnings: “It makes me sad to see this wolf eat the pigs, because we saw their mother, and they are the good guys of this story; after all, the book is called ‘The Three Little Pigs,’ not ‘The Very Hungry Wolf.’”

I’ll beguile them with a switch up from their previously satisfied interpretations, adding, “But I can’t help but wonder if this is just how the food chain works, and is that okay? I don’t know if the Big Bad Wolf is so big and bad after all.” I widen my eyes and grin in bewilderment as we encounter the unnerving feeling of a potentially untrustworthy narrator.

I ask questions that are impossible to answer, but answers aren’t as important as the habit of doubt. They’ll begin to extend their empathy in unanticipated ways; they’ll begin to integrate other fields of information, and they’ll begin to doubt their archetypal assumptions: they’ll begin to think critically.

As a kindergarten and first grade teacher, modeling was the pedagogical strategy that I used most frequently; it was the most developmentally appropriate strategy, as well. Once learners pass the threshold from learning to read to reading to learn (on account of their increased reading comprehension skills), they’re more readily able to acquire and situate knowledge through reading and listening. But before this transition occurs, younger learners at roughly seven or eight years of age who are developing skills—such as walking, reading, or thinking critically—require an embodied approach for most of their lessons.

When I state that I spent my early career doing thousands of hours of modeling, I know what that conjures up. Although this form of modeling was fun and performative, it was anything but shallow. Jorge graduates first grade at a third-grade reading level, and Lilliana at a second-grade level, and the vast majority of my class also learns to read beyond grade-level proficiency. This is an immense achievement for all of us—our school, the families, the students themselves, and of course me, their deeply proud teacher. In a nation where prison engineers speculate on future incarcerated populations based (in part) on third grade reading scores, my modeling has helped a small portion of my community to conquer the carceral state. I have the utmost respect for models, for modeling is a life-changing, impactful skill.

The first model I ever learned from was my mother. She taught me my first words and steps, and even made a song to teach me how to spell my name. She taught me how to manage a city with requisite wonder and suspicion, observation and belongingness. She taught me how to do most everything a mother might, on purpose and by accident. Not the least of these lessons, somewhere between the intentional and unintentional teachings, were grace and beauty and femininity. Before I was born, my mother was a professional model—common usage here—on runways, in studios, in advertisements, in magazines. She is strikingly beautiful, both conventionally and non-conventionally. She is a dark-skinned, slim, soft-curved, athletically built woman, with a very tiny head. She says that nobody took pictures of her when she was a child because she was too ugly, but I have seen two or three photos of her as a kid, and it isn’t true; just that she was dark-skinned and kinky-haired and couldn’t access appropriate health care for her eczema. I’m well aware how the unseemly residue of historical transatlantic hierarchies based on ethnic and phenotypic valuation would cause her to remember her youth in that way.

When she grew up, she became legibly beautiful, in no small part due to her intense, big, bright but deep eyes, and perhaps, the autonomy to get her hair relaxed. As a child, I admired this glamorous career of her pre-me life, awed at images of her in glamorous environments and ideal lighting, her hair and makeup and outfits polished and perfected, her posing so clear in its narration, calm or cheery or seductive or peaceful. I never imagined I could fit into this ideal feminine format, but I did try once, in fifth grade, to fit into an old dress she had modeled in, for my role as Billie Holiday on biography day. Being a larger dress size at ten than my mom was at twenty-five, I became disappointed to learn what I’d suspected: that I may never grow up to fit into her dress forms or performance forms, or most other model-like forms—that I would have to shrink to fit in to this form that I’d worshipped and learned so much from. Feeling quite enormous, I hypothesized that at this trajectory, the things that were beautiful about me might never be legible, but maybe, like my mother would come to find only later in life, they would.

Despite my failure, it remains a great psychological comfort to have a mother who is known as such a model, in part because even when I’ve felt ugly, a piece of me knows that it’s just happenstance, not down to the bone, an unfortunate glitch in the genetic recombination, rather than an indication of what the public (accidentally eugenic as our beauty preferences sometimes appear) might see as the quality of the genes themselves. And because of this ironic fashioning – to be inheritor of, but not quite capable of—I also feel there is something awry, here. There is a thing (or, demonstration of beauty) lingering, too bound up in the accident of birth. The apparition of beauty speaks of proof, of breeding; but I cannot, or will not, abide it.

Many models today are inheritors: literally. Their mothers were more successful models than mine, and therefore their fathers were more successful businessmen than mine, and they can afford far more of the trainings, and trappings and shavings, the tricks and sleights of the deftest surgical hands, or rather, remodelings (or beauty privileges, that are not merely about beauty but position from whence to beautify) that make a model, than I can dream of affording. I won’t deign to judge what I can’t opt into, but today’s beauty seems so readily bought and sold and deeply bound up in the “if you can afford it-ness,” logic of late capital that I wonder if part of its performance is about access to superior elective procedures.

The market today is replete with heiress supermodels. Genetic inheritance, or willingness and ability to revise said inheritance with some anesthetic risk, then takes on key importance in the business of modeling. Perhaps this will ultimately give way to a democratized understanding of beauty: to know that it can be willed, or that it can be bought, and designed, moves beauty away from the incontestable genetic display on the body to the planning and intentions of the mind’s eye.

In contemporary popular communications, “modeling” has been thinned out to signify a profession and action that is marked by the influence of multinational conglomerates, precipitating a crisis in textile and plastics pollution, through a pseudo-seasonal production cycle that banks on cultural extraction, abusive labor practices, exclusivity, and the psychological control of femmes and femininity. In conversational shorthand and based on the top answers on a Google search, the word refers to a fashion model, seen on a runway or in a magazine editorial; or a commercial model, seen in advertising campaigns or catalogs; and of late, the Instagram model.

Fashion models are the most esteemed of the category, and the rarest. They are known for their unique physical countenance, taller-than-average height, narrow body shapes and long-limbed grace, and above all else, their ability to look good in most clothes. The turn of the millennium saw the dusk of “heroin chic,” ushering in more athletic and slightly bustier model bodies in the aughts and, in the teens, a partially positive enthusiasm around representation in media and the arts (and most notably, in governance) led to the increased inclusion of plus size or curve models, frequently sizes 8—12. (For context, the average American woman’s clothing size is a 14.) Commercial models by comparison tend to be a bit shorter, and among them, possess a wider diversity of thin and athletic body types. Facially and phenotypically, they are more common. The recently problematized hit show, America’s Next Top Model, for lack of a better source, suggests that someone who fits the “girl next door” archetype is best suited for this type of modeling—their supposed relatability is a marketing asset.

Instagram models are the most recent entry to the prevailing working definition and offer noteworthy innovations on previous industry standards. Like commercial models, they are known for their relatability, although this stems more from the way they relate and come to be than their physical appearance. Social media’s channels of distribution give these models more control over the images they share, as well as individualized capacity to narrate; it expands the selection of specialized aesthetic niches that can be modeled, and (supposedly) puts the power of approval and celebration into the hands of the everyday social media user.

Instagram models, as a newer and nascent form, often usher promising destablilizations and innovations. Some Instagram models’ performances harken to commercial or fashion modalities and may even perform these modalities so satisfactorily that they go on to the traditional agency systems. Still more will remain independent, with the occasional opportunity to profit from their image-making via brand partnerships. This is similar to the path of an influencer, who might also make brand partnerships. In fact, an influencer who is more akin to a model, who possesses both the community believability of a thought leader, along with the photogenetic power of the modern model forms, is more likely to acquire brand partnerships and the social and material trappings therein. Crucially, in the Instagram model is a potential reversal of the spokesmodel pipeline, wherein celebrities and esteemed artists promote products. (There, the suggestion is clear; the everyday consumer who opts to purchase and make use of those products might also be as elegant, talented, and refined as the spokesmodels shown using them.) In contrast, an IG model might tag a product or venue or destination without remuneration, and be offered a chance at higher circulation of their image, diction, and lifestyle, as well as the prestige that comes from institutional or brand recognition.

This circularity presents a risk for all social media practitioners who offer goods, services or expression to the general market: what sort of acknowledgement is requisite to enshrine and delineate a worthwhile public figure? What becomes of the public figure who lacks brand or institutional recognition? Or more pointedly, how does this recognition augment or contract one’s ability to make and distribute public creative works (as goods or services), with or without brand backing for that particular work? Do those who more closely represent a model physicality stand a greater chance at influencing others? And if so, what are the risks associated with this accrual of influence to a particular group of individuals?

Across these three categories, the role and representation of the model has shifted. Today’s modeling aesthetics appeal to the viewer’s hunger for authenticity and intimate proximity. The need has been driven by popularity of off-duty snapshots in gossip rags and entertainment news, blogging, street style, celeb-reality programming and diaristic social media trends stretching from the early millennium to the present day. There is an opportunity, or perhaps, if less favorably understood, a demand, for a more vulnerable sort of exposition—a peek into the model’s thoughts, lifestyle, friend group, her home and her humble “off-duty” moments. This new modern model rips at the previously clear distinctions between what is lived and what is produced, what is self and what is product: what is believed, and what is branding?

Each category of model interacts with the others, and they all interact with a larger dialogue around aesthetics and the body politik. This is not new. In the mid-’90’s, the dusk of the era of the supermodel, mental health and eating disorders, in particular, had become an international preoccupation. Very thin models began to go out of style. The increasing profile of women’s sports, and the founding of the WNBA in 1996 and the USA Women’s National Soccer Team victory in 1999 may have shifted tastes toward more athletic body types, as well. The commercial success of the Sports Illustrated Swimsuit Edition, and the increasing popularity of the Victoria’s Secret Fashion Show likely impacted the high fashion modeling world. Hip widths and breast sizes began to increase on runways. The diversity and inclusion fervor of the turn of the millennium changed not just corporations and workplaces, but also whetted an appetite for representation of fuller-figured models.

While technology has enabled mass media to become more all-encompassing, or massive, national politics have long coerced expectations in fashion and women’s public appearance at large. Many scholars have noted links between the popularization of the term “flapper,” (slang for teenager and/or prostitute) and widespread anxiety over women’s suffrage. Half a century later, the first ever Fashion Week was held in New York in 1943 to give buyers an alternative to sourcing from France when international travel was limited during World War II. Three years later, textiles were in short supply postwar. Two French designers created the modern bikini, which they named after Bikini Atoll, the site of the first US nuclear weapons tests in the Marshall Islands. They kidded that like the atom bomb, the bikini was “small and devastating.” Many feminist theorists and cultural historians have explored the linkages between the midcentury archetypification of “the bombshell” and of course, the emergence of a performative masculinity that could contain her.

Today, sociopolitics—currently in combination with digital consumer technology, rather than defense technology—dictate the contours of the inception of the “IG model.” Changes in camera, phone, and cellular technology, early 2000s blogging, street style photography, celebutante culture, and the paparazzi era all popularized more urbane, casual fashion and lifestyles. This period influenced both today’s purveyors of high fashion, who regularly aim to contextualize models in lived rather than exceptional settings, as well as everyday exhibitionists and posers on social media. This moment is a powerful yet uneasy boon to modeling and the amount and exercise of a model’s autonomy in particular.

“The IG model is a media pioneer: they do not wait to be seen or selected. They control the means of production, and they’ve got a trusty “in” with the casting director. They wrest beauty and attentionality from the traditionally repressive selection and exclusion process, and seemingly, the machinations of the gaze at large. They perform without permission from the power holding structures of image making and distribution, and in their mere insistence on being seen, every IG model is an influencer who says: Me, and people who look more like me than they do the average fashion or commercial model, deserve to be seen and glamorized, too!”

I struggle to define what separates an IG model from an influencer, not for lack of ability to sort and categorize, but because of the lack of a discriminate category. An IG model frequently performs culture, lifestyle, political leanings—entire value systems— as part of their job. Their curation and authorship are implied, in contrast to a professional fashion or commercial model who might get paid to represent the expressions or products of an unseen author, designer or proprietor. In the IG model world, authentic context replaces professional production, but there is no net loss: the value of the IG model is largely buoyed by the fresh and relatable inventiveness of amateurism.

The IG model is a media pioneer: they do not wait to be seen or selected. They control the means of production, and they’ve got a trusty “in” with the casting director. They wrest beauty and attentionality from the traditionally repressive selection and exclusion process, and seemingly, the machinations of the gaze at large. They perform without permission from the power holding structures of image making and distribution, and in their mere insistence on being seen, every IG model is an influencer who says, me, and people who look more like me than they do the average fashion or commercial model, deserve to be seen and glamorized, too!

I’m not sure that being seen is enough. Perhaps this seat at the table is merely a reflection of a growing population, a concession to the unwavering force of the desire of people all around the world to be understood as beautiful, ushered in by a massive, unpredictable, and unmanageably abundant rollout of user-generated content. Or pessimistically, this inclusion might be a means by which to placate consumers and draw them back into their retail base, as when Shea Moisture, popularized in online Black natural hair communities, sold to Unilever.

Increasingly, I’ve grown dissatisfied with mere representation. Just as so many of my peers had to revise their excitement about a first Black president, I’ve had to ask: what is done with the power, space and attention that are called for? That is, what is the representation in service of? Or is it an end in itself? And if so, does it pay off in the ways that a kernel within my unconscious mind expects? This era of representation has been flimsy, but I cried when Barack Obama was elected: I’ve been flimsy, too. Perhaps, as with the pitfalls of presidency, the moment at which a previously under-celebrated group is finally understood as beautiful in the mainstream is the moment at which this representation ceases to have revolutionary potential. And perhaps the scheme whereby liberation is brought on by representations of modeled beauty is inherently flawed: as much as a model might be a more physically proximate representative to an under-celebrated group, a model is understood in society as a superior figure, but not an exemplary one.

Now, we are beyond the limits of how a model’s role was previously understood, and because of the interventions of social media modeling and blogging, we sit in a landscape where supposedly anybody can be a model. In this moment, I’m most curious about those modelings which are embodied, but less about the body itself. That is, in the wake of the democratization of the model, and the redistribution of the model’s glamorous positionality and social currency, how are less physical moments—the unposed, the ongoing, the building and revealing and restructuring of thought, for instance—rendered unseen, and more profoundly subordinated?

We have adjusted the who of modeling, but should we have instead adjusted the how and to what ends of modeling?

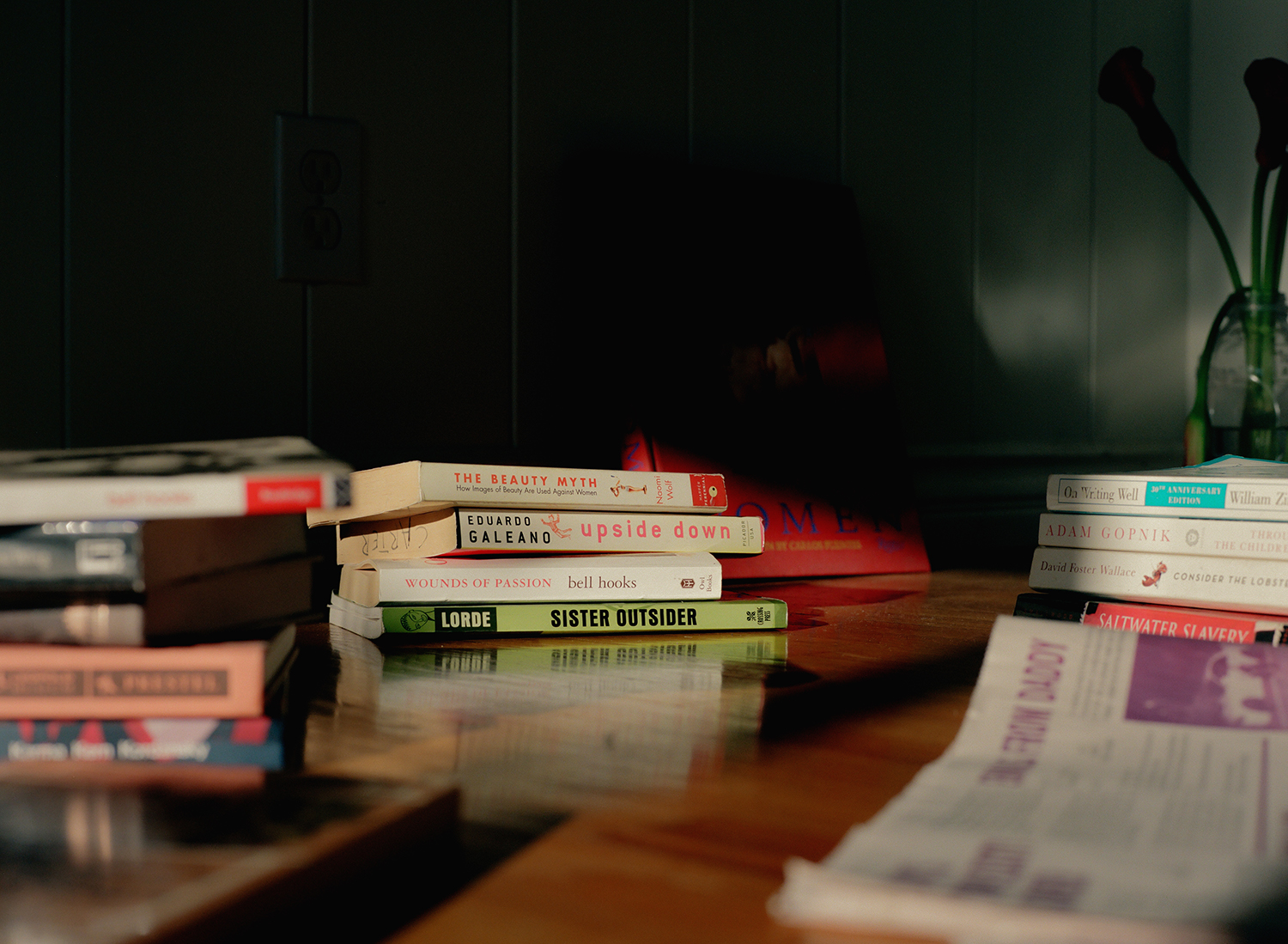

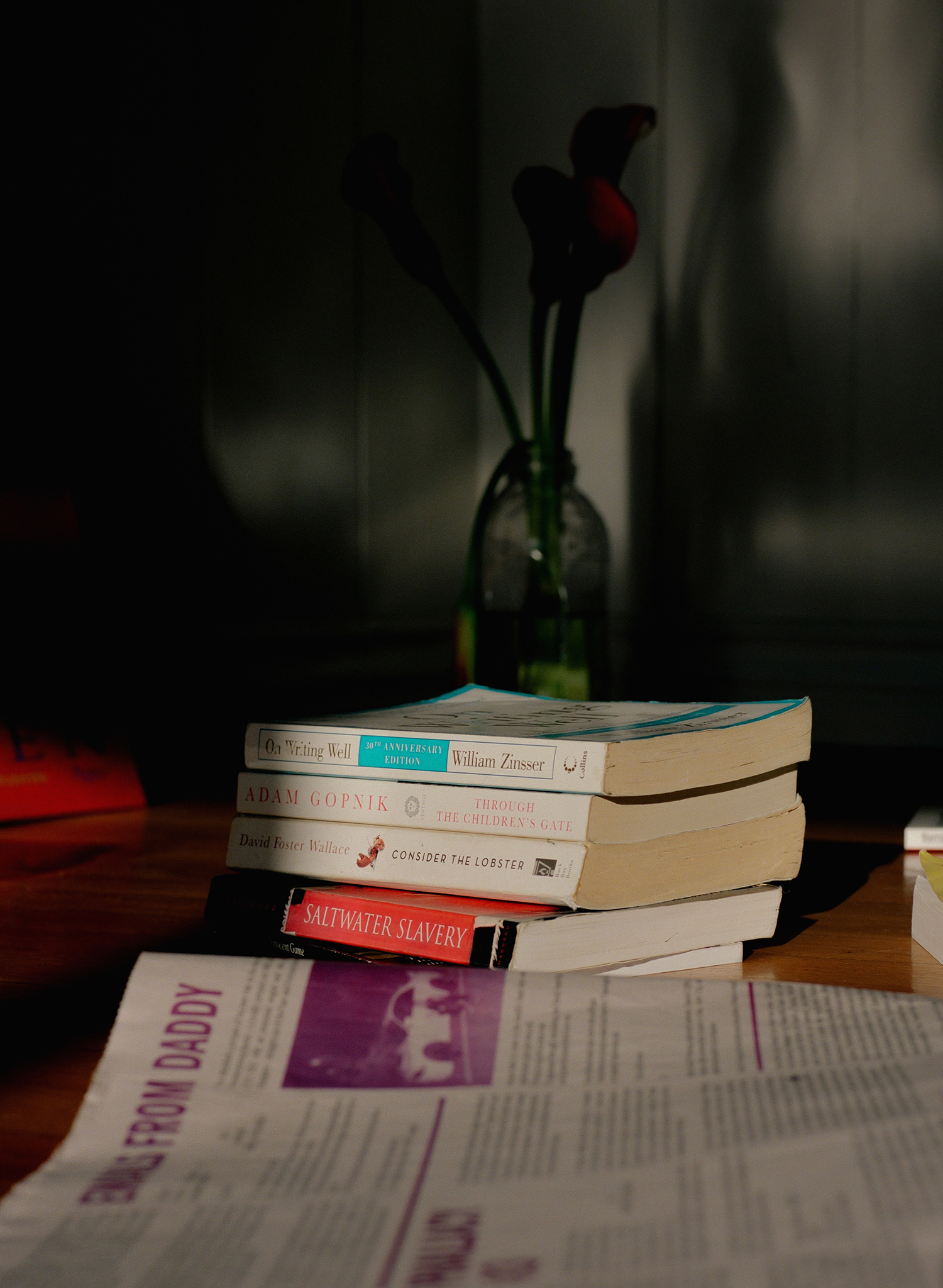

I find myself, several years into my participation on Instagram, dismayed and let down by many model-activists who I once believed might act as vital Trojan horses for critical theory. I confused representation and performance of movement-based slogans with belief. I confused hashtags, language and even “shelfies” of the finest critical texts with praxis. I pushed onwards through the feed without stopping to process that which was not immediately enjoyable or comprehensible, imagining that the models were doing the work to save the world so I wouldn’t have to read too much. I have been shallow in ways that I’m disappointed to admit. In our rapidly accelerating media landscape, I too, am learning to become quicker at suspecting smoke in mirrors, at noting precisely how dominant norms, including beauty, diversifying as they may appear, are intimately beholden to a nation’s more regressive habits of thought.

Professional fashion and commercial models now experience pressure to share their authentic selves, and may do so out of inspiration, or, equally, competition. What may have been a moment in a model’s day, a mere professional experience of a shoot or show, now seeps into personal life with material consequences. The model’s ability to convey the performance requisite to their professional assignments is now in conversation with what the model chooses to convey outside of these assignments. Their diaristic glimpses dialogue with the viewer’s ability to buy into the model’s potential promotional performance.

With castings and day rates in the balance, how does the omnipresent documentarian reflexively impress its gaze onto the contents of the document, and before that, the world of feeling— the performed living itself? In a stream of visual information, how does a model (and their viewer) discern what is meant to be authentic and what is modeled? Will we always struggle with this awkward positioning, this looking around the corners of our body, the cumbersome strain of looking natural? Does living become a preface and context for our cardinal (paid) performances? Where does performance begin and end?

“We have adjusted the who of modeling, but should we have instead adjusted the how and to what ends of modeling? I find myself, several years into my participation on Instagram, dismayed and let down by many model-activists who I once believed might act as vital Trojan horses for critical theory. I confused representation and performance of movement-based slogans with belief. I confused hashtags, language and even “shelfies” of the finest critical texts with praxis. I pushed onwards through the feed without stopping to process that which was not immediately enjoyable or comprehensible, imagining that the models were doing the work to save the world so I wouldn’t have to read too much.”

Most seamlessly executed, a model, like any other performer, becomes completely harmonized with their role. And so, critical faculties are required of the viewer, of any person using social media, to investigate this rapidly evolving, increasingly normalized set of poses.

The seeming opportunities for authenticity and autonomy are compromised by the same technology that enables them. Socio-structurally, it’s complicated to identify where lowered barriers to distributing images and videos crosses the boundary between opportunity and responsibility. For those of us who trade in the public arena, whether modeling or not, this surveillance impedes how we live in ways we have not seen the end of and cannot yet conclude the effects of. Quantitatively, social media algorithms programmed with little to no transparency determine the distribution potential of an account or individual image. More ephemerally, interpersonal, societal and political algorithms have always determined what and who is understood to be conventionally attractive—worthy of attention, love, celebration, and positive reinforcement.

But technologically revolutionary as they may be, social media platforms were introduced into societies with longstanding aesthetic and political values. They haven’t and likely never will completely do away with the obsolete aesthetic valuations and systems of ranking bodies that were so instrumental in the founding of the Western world. Ultimately, it’s difficult to discern whether an algorithm learns to determine which models are most deserving of attention from its programmers or its users. Here again, a supposedly liberatory reclamation of aesthetic, personal, and political autonomy is manipulated and tempered by the projections of the powerful.

Successful modeling enlists —and this goes for pedagogical modeling efforts, too. Most sorts of modeling draw attention to the self but aim towards collective purpose and action. What an exquisite duality of engagement! Buy in is essential: in the premise, the execution, and the outcome. The goal of many types of modeling is for one’s skills and habituations, personal qualities and habits of character, and experiences of pleasure (if not totalizing ecstasy) to be made attainable all for the price of engaging in the call to action.

Might this also apply to habits of thought? Or is the process of acquiring thinking skills too protracted, and so, too unattractive in comparison to easier acquisitions? For instance, many prefer to use language derived from movements built on the work of critical thinking, without change in their actions.

The call to action is best suggested subtly. Why yes, a model performs on behalf of a product or a brand, but they aren’t just modeling the thing itself. They demonstrate the thing satisfying human needs, with wide eyes and satisfied grins, with heads tilted back in ecstasy, mouths slightly agape. Or, they model anticipation by looking coy, attracting a model of the opposite sex, positioned to the left of the model’s center, gazing hungrily at the center of attention. They don’t model the how-to technicalities, so much as the payoff, the endgame.

A model performs the confidence that should ostensibly be felt at experiencing the product. The model shows you how good it will feel when you acquire said thing. There is an inherent if/then speculation, an act of showing and decoding, which is most likely actionable: if you are able to perform a discrete task, you can achieve the social or attitudinal state of the model. With the exception of figure modeling (wherein the model’s purpose is to be observed, rather than seen or interpreted, and to endure rather than express) most modeling, including pedagogical modeling, is instructive.

There is artifice in making certain acts of reading look natural, or easy, or fun. I love reading, and I’m an appropriate and earnest exemplar when modeling it. But I’m aware that I’m putting on, and perhaps, overselling the likelihood of bliss, just like any other model might. But what is dissimilar about the modeling that I’ve done to teach critical thinking, is the duration, the amount of buy-in, the stability and consistency of the performance.

If the goals of modeling are predominantly prescriptive and the act of modeling is ever expanding, we ought to get clear on what is being asked of us as viewers, and potentially even as models ourselves. Why do models perform for imagery to be shared and distributed, and towards which ends? And since all performances are inherently political—they utilize capital as their medium to make with or move through, as space, time, currency, or all three, capital that is distributed per political systems, per adherence to social norms, — we should update our understandings of what modeling might mean and what it might offer.

Most modeling is not in service of one’s own most pressing beliefs. So what are the political implications of corporations enlisting specific cohorts to engage the masses, toward ends of discrete consumptive behaviors? I intend not to criticize any sector of modeling or any one model, but rather to encourage that we must become curious about this increasingly democratized and distributed practice. We might become so curious that we evolve the potential power of this enormously influential, increasingly regular act. We might ask: Is this act promotional or expressive? If promotional, what is the product, service, event, lifestyle, or trend that is being promoted? If expressive, what is the thing that is being expressed and why, and how do material investments and profits operate around this expressive act?

“If the goals of modeling are predominantly prescriptive and the act of modeling is ever expanding, we ought to get clear on what is being asked of us as viewers, and potentially even as models ourselves.”

Perhaps we owe a more patient vow of respect to models in our midst. We might consider what emotions and embodied experiences are being performed and by whom. We might notice sartorial touches and what they are meant to convey, both historically and in each visual context. We might begin to slow down and notice the scenery, and props and hair and makeup, contemplating the traditions, and inspirations, deepening our appreciation and knowledge for the historicity, meaning and textuality of images, their total composition and the details therein.

Where our current platforms urge hasty and automatic consumption, I suggest that we need to slow down.

My primary inclination, to inspect the act, the art, and the vocation of modeling is philosophical and strategic: in a world full of beauty, what must we beautify? What behaviors must we model and how will we glamourize the most necessary behavioral changes so that we might make more freedom and justice for all?

My secondary inclinations, to remind myself to slow down and think critically about modeling are linguistic (etymological), erotic, psychological, sociological, evolutionary, and analytic. The linguistic impulse is the primary conceptual framework of the piece before you. How is it that this word, “modeling,” which means so much, has become so specific in popular usage? What social and political and economic forces conspired to supplant the one definition for the many? What consequences and opportunities have emerged?

“Where our current platforms urge hasty and automatic consumption, I suggest that we need to slow down. My primary inclination, to inspect the act, the art, and the vocation of modeling is philosophical and strategic: in a world full of beauty, what must we beautify? What behaviors must we model and how will we glamourize the most necessary behavioral changes so that we might make more freedom and justice for all?”

The erotic impulse is born of my experience: that taking time to notice increases pleasure. The ways that we process stimuli or opt to engage in delighting our non visual senses encourages aggrandized lingering. For example, when we first endeavor to eat, both sight and smell prompt the palate and stimulate the salivary glands; we chew our food, rather than swallowing it whole—there is a digestive instinct to break down the mass before swallowing, and this requisite durational effort leaves us with time to relate to the bite’s texture. Mouth feel affects our impression of flavor, which will come in stages: we first smell dominant frontal notes which give way to richer mid-palate flavors.

We may also experience multiple stages of tasting in one bite, in part having to do with how long each composite ingredient takes to break down, and the positions of said ingredients in our mouths. Seeing, on the contrary, is our most automatic sense. We have language and logic, concepts of organization, analysis, and valuation for most things we see. Putting the experience of less dominant senses into words, much less comparing/contrasting or building systems of logic around them, is a creatively enticing, elusive, and imprecise endeavor.

Might we gain more pleasure if we savored images slowly, considered them patiently? Might we feel more pleasure if we learned to describe images with vulnerability, with of a description that grasps or hints at, rather than references what’s readily observable, what’s conceptually fixed, of predetermined value? One might take inspiration from games and pastimes built solely off the thrill of this nuanced communication: the card game Taboo, and the more contemporary Heads Up. We play games of gesture without language like Charades and illustration without language—Pictionary—which model diverse methods of non-verbal communication.

I speculate that the reward of describing images is an augmented sensitivity, and further that clarity of communication prevents harm. Consider the problem of racial identifiers: Black is not the color of the thing it refers to. There’s great, contested ethnic and cultural variety to what might phenotypically, or visually, produce this identification, and so ultimately, the identifier rings hollow and ineffective.

My psychological, sociological, and evolutionary concerns around the volume of visual information we take in, their conceptual load, all bleed into one another. There are more images created and distributed and at greater distances and more instantaneously than ever before. Consuming hundreds and thousands of images is an increasingly normal practice for a large and growing sector of our global population. Like many social media users, parents, scientists, and Luddites, I fear that the speed of technological innovation dramatically outpaces study about social media’s psychological and cultural effects: What happens to the brain when exposed to so much visual and social information? I fear that there are not yet well-honed and widespread best practices for safe and affirming usage.

“Perhaps more of us are modeling, and more frequently and promotionally than we think—laying groundwork for an eventual purchase, unbeknownst to us. Our success on these platforms is more and more socially and professionally consequential, and determinative of political, financial, environmental, and biological outcomes. While we share the same airwaves, we do not share the same resources toward gaining attention or virality. We do not all have professional hair and makeup and lighting and art direction. We do not all have the same styling, and like it or not, we do not all possess the same conventionally recognized beauty.”

I’m especially disturbed by the legislative lag, the lack of government oversight that permits a galling latitude for tech companies. Their popularity is more encompassing and addicting, and consequential to global politics, than any other product or service that might have been regulated before them. Their addicting quality is in large part perfected by the algorithms, which organize photos and videos in precisely the most effective way to keep you on the platform for longer, and prime you to buy from their malls and vendors. It is this exact formula, this proprietary blend of algorithmic manipulations, around which big tech maintains such impenetrable secrecy.

I’m here reminded of the role of the model: to seduce the mind into a charmed and attracted state whereby a behavioral suggestion, typically to pay for a service or good, can be readily acted upon. It is their prioritization, not their mere juxtaposition with the day to day, that is of concern. Models, paying advertisers, and professional imagery experts are interspersed among more casual, or amateurish offerings of livelihood—intimate and personal relations collapsed and evaluated back-to-back, all vying for our approval. Moreover a vast number of parties all compete for feed prioritization: our colleagues, friends, and loved ones compete with needed dialogue around values and politics, which is up against helpful, curated information amalgamation, alongside professional and/or community-vetted health and lifestyle expertise, next to access to corporate and independent journalism, infinite types of information carousels, and finally, models, both in ads, or in their private lives. The for-profit feed increasingly leads us to a point of sale. Is it not quite likely that the algorithm wants us wanting? Isn’t it conceivable that every post is prioritized per its likelihood to prime us for purchase?

Perhaps more of us are modeling, and more frequently and promotionally than we think—laying groundwork for an eventual purchase, unbeknownst to us. Our success on these platforms is more and more socially and professionally consequential, and determinative of political, financial, environmental, and biological outcomes. While we share the same airwaves, we do not share the same resources toward gaining attention or virality. We do not all have professional hair and makeup and lighting and art direction. We do not all have the same styling, and like it or not, we do not all possess the same conventionally recognized beauty.

My tertiary instincts are baser, more personal, less noble and intellectualized. I suppose I’ll summon bravery and confess them as a means to lay down my burden and triumph over shame, as a model of vulnerability, rather than avoidance or internalization—for the vast majority of times I bear my most honest thoughts in writing, I am joined by comrades of sense and sensibility: I fear that I am frequently unphotogenic. I feel betrayed by my posture, I know I should exercise more and eat less, I want to run and hide, and give up, and every so often I do. I shrink my aspirations to share myself in public performance, the performance of self as a public figure with just under sixty-thousand followers, the performance of thinking feels so difficult to sell anyways, what with such quick and facile viewer payoff, just a swipe away. I’m not sure if I’m cute enough to get people’s attention to get my point across. [With regard to the process of essay, I frequently found myself shrinking away. You should know as you read that this essay comes submitted at a very late hour months after it was promised. I begged for the most stringent critique from my editor. I am aware of the tendency to try to live within the space of my writing, and this is a comfort that gives too much slack to the rigor of the argument. I confess this magnetism to alert you to efforts to avoid it.]

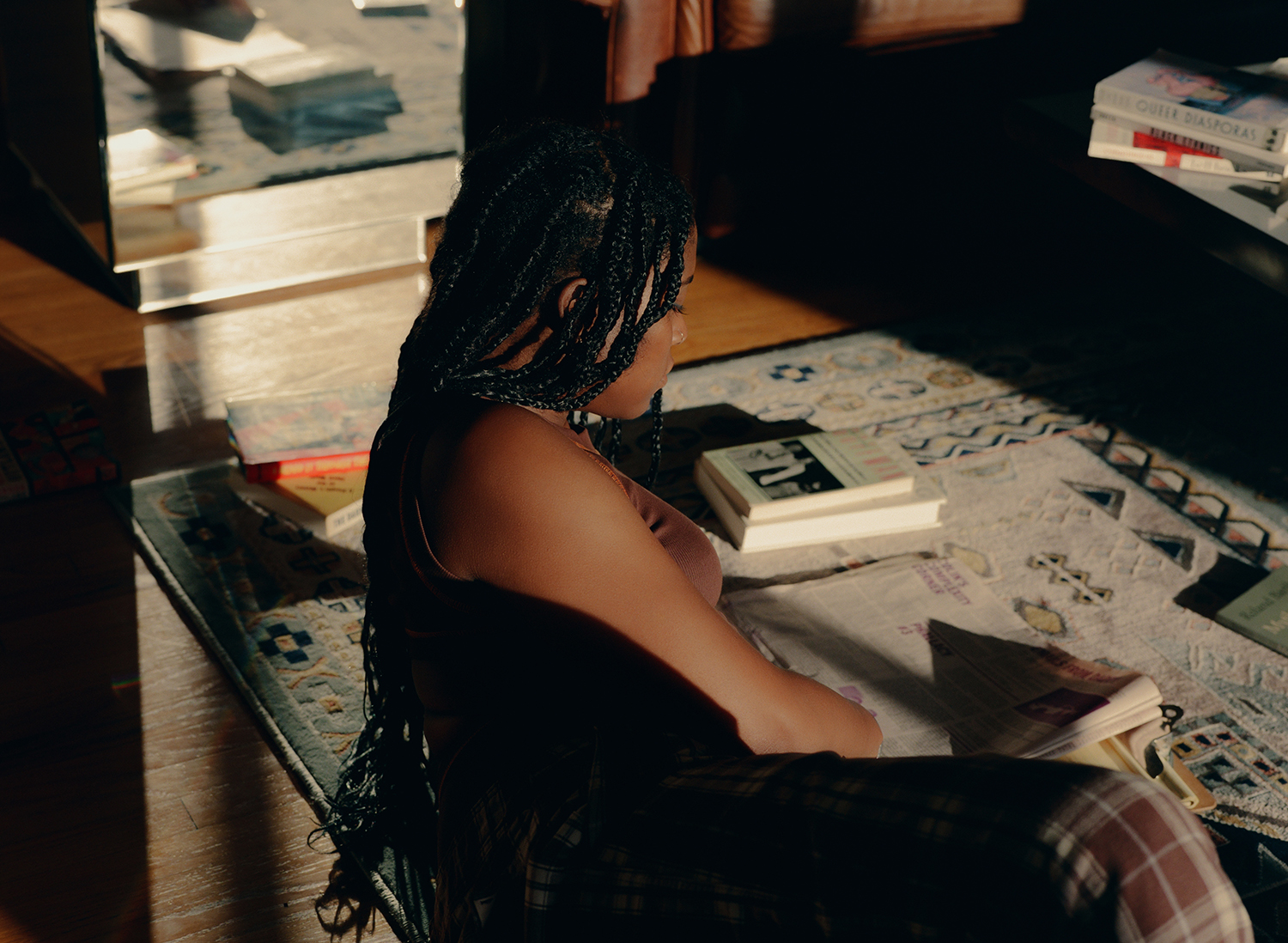

In my day to day, this set of concerns is material, administrative, egotistical, and vain. I recently added some long kanekalon braids to my natural hair and thereafter received several invitations to model for brands and companies (commercial), as well as a collection of less formal Instagram modeling opportunities. I am alarmed by this simple trick of visibility, how adding length, volume and style contributed to a more easily legible beauty— so legible in fact, that it should be called upon to promote goods and services!

At the onset of Pride month, I confronted my image on multiple wheat pastes throughout the city where I live. I also confronted the knowledge that I do not know how many people have seen it or judged me. The experience was exciting and disorienting, and made me self-conscious. I don’t quite recognize myself in these formats, nor do I think that I should. Do I really look like that? I thought I was cuter. Seeing a less cute version of myself, enlarged and widely distributed for a national wheat paste campaign stokes feelings of shame and failure at underperforming, I had a regretful, almost trapped feeling of a lack of control.

I’ll admit that commercial modeling is not the creative practice closest to my heart. I am conscious of the fact that I have participated in this game that feels unwieldy and unfair. I’m looking for “get rich quick” schemes, and it has everything to do with a commission to make an art film which will show at a prestigious biennial in the winter, a film which my producer and I cannot make with the funds I’ve been allotted. And the shape of my bank account now has everything to do with the life path I’ve chosen, far less profitable than the peers with whom I graduated. I didn’t accept all of the offers to model. I turned one down because there was some language I couldn’t quite square away with my beliefs. But as complex as capitalism is, as is every act of modeling within it, I can’t say this latest round even compares to the least ethical modeling work I’ve done. I modeled for a brand that utilizes deeply unethical labor practices, ones that I was fully aware of, in part because at the time, I was a full time artist, with no regularly paying job, and I needed to pay my rent, but I’m not sure if that excuse is good enough.

I’ve learned that if I prioritize beautification, adding elements to my appearance that more comfortably and conventionally situate my visage within that which reads as feminine and pretty, I stand to gain money to support my art. And the likelihood is that if I can make some more time to practice flawless posing, and maybe add a little makeup, that I can increase the regularity with which I can raise this sort of capital. It is not lost on me that if I were not as conventionally cute as I am, I would not have the money to fund my film: capital makes more capital, and although I realize there are plenty of ways that people make money to make art, this one feels especially unfair, and especially tempting.

Through this most recent experimentation, I’ve grown an awareness of how I would like to model and how I would not like to model. I consider the precise instances where consent felt insufficient, where there were points of tension in my performance; I remember the flattery of being asked alongside the risk of embarrassment balanced with the possible boon of augmented social, professional, and real capital. In the future, I would like to be involved in processes where I have more direction, control, and final say over how my image is used. I would like to smile. I wish to create images that are imagined by me, performed by me, and approved by me, but the fact that I’ve closed the funding gap for my first solo film reminds me of the eternally uncomfortable negotiation. Which artists and public figures among us could be truly said to have complete control over their image?

While we know that models are artists, we don’t often acknowledge the inverse misfortune: that all artists would do well to be models these days. The rules of the algorithm are opaque and yet obvious here: show your face, and frequently, if you’d like more attention for your artwork. Our genetically predetermined countenance has always determined our access to get the means to make art, and in the social media era, there is the persistent temptation of our work being potentially seen at any given moment, if only the channels are warmed well enough.

The greatest equalizer in my own creative career has been visual-based social media. Without the backing of an art school or journalistic degree, and somewhat unsure what good either of them might do, I have been unexpectedly successful in utilizing images to draw attention to my creative practice. To feed and ingest what my algorithm brings to my attention has been confusing and revealing. Merely by calling up an image, whether for approval or assault, engagement increases popularity. This clickbaited-ness, this popularity that plays as quality of seeming approval, is effectively an anti-quality control.

“While we know that models are artists, we don’t often acknowledge the inverse misfortune: that all artists would do well to be models these days. The rules of the algorithm are opaque and yet obvious here: show your face, and frequently, if you’d like more attention for your artwork. Our genetically predetermined countenance has always determined our access to get the means to make art, and in the social media era, there is the persistent temptation of our work being potentially seen at any given moment, if only the channels are warmed well enough.”

In this landscape, a more intentional and deeper conversation with what images are brought to our attention and why, and to what end, is a powerful balk against subliminal commercial, political, and social programming. But to divest models and the art of modeling from playing a role in a potentially more liberating performance would be a grave miscarriage of the power of the well-composed image and the well-poised model. There is reason for both caution and optimism where the act of modeling is concerned. There is a need for analysis, especially around costs, profits, demonstrated values and actions, and desired outcomes.

As an artist who uses their body, their visage, their physical performance, I am drawn to the format while being frustrated by its norms. I am invited by the opportunity but frustrated by my lack of ability to assert authorship. On the one hand, a well-performed self is an art form. On the other hand, the investment in my physical upkeep, to signify a willingness to be seen and achieve regard as worthy of being seen, is costly, where time and money are concerned. The arrangement winds my mind into exhausting probabilities: how much weight should I lose to attract attention to the argument I am making? Would plastic surgery or a filter help me to further distribute my ideas?

And of course, there is the more precisely maddening inquiry: how much more or less effective would the art I’m making, born in part from the distance between my body and the ideal Black female form (if there can be said to be one), be in a more idealized body?

In my practice, the performance of the work is part of the work. However, this is not the case for many artists. The pressure of having to show up and perform as an artist, or having to model artistry and the artistic lifestyle is untenable, distracting, and sometimes desecrates the messages of the work itself. And should I fail to show up with a well-executed focus on my physicality, how will this slant the acknowledgment or criticism of my work?

Having gained a following in part based on my own image, but certainly via multiple other visualized gestures, I now carry a blue check beside my name on Instagram. I daily consider the guilt of belongingness in this corrupted system. I meditate on the problem with the perceived democracy of this platform, combined with the invisible sorting hand, an opaque value system ordering what is to be seen and what is to be shadowed. I question the “verified” status, with little to no transparent vetting process, the lack of clear means for the everyday person to ascend to this designation. The check gives a sense of note, of record, the impression of authority, which condones all of the actions I make as a result of my online popularity and status. While I’ve worked to give a different sort of self-performance than the typical modeled one, the idea that the power to distribute information widely with certitude can be gained primarily via impressive photos is deeply troubling.

Stills and snapshots, coupled with socio-political utterances and hashtags, prioritized in part based on human-programmed and machine-learned adherence to quality and beauty, too often mock the real processes of social and political awareness, community building and co-learning, and world re-fashioning. Too infrequently are we privy to the process by which one acquires such knowledge. Too infrequently do we understand how an individual has integrated the meaning of the oft- captioned “Black Lives Matter” into their livelihood, and too infrequently do we see this conviction play out into real life. It is far more easily hashtagged than done, to create an interpersonal discipline and materially consequential habit that enhances the lives of Black people so that they feel that they matter. There is too frequently an inherent discrepancy between the entities for whom we model, and the marginalized people whom we seek to defend. We take jobs for companies that have failed to abide by ethical manufacturing practices; we model in brands that have sordid histories for which they remain unaccountable, and we proudly tag the threads of the designer who was recently embroiled in this or that racist design or depiction.

“… The model who can and will popularize critical thinking is rare, but not impossible.”

What results is a confused populous: one that misunderstands the interaction between what we stand for and how we perform and for whom, one that learns to acquire social capital from the language of movements, without a clear understanding of the history of organized individual and collective efforts to arrive at such declarations. This populous misunderstands how one might independently arrive at such beliefs, via proof, or study or argumentation, or reasoning and logic.

Only a precise combination of the positionality, and the democratized habit, the juxtaposition, the access, the investment, and the transparency of modeled thought or direct action, enables real social advancement from the popularity of modeling. That is, the model who can and will popularize critical thinking is rare, but not impossible.

The role of the model and the role of the independent artist are seemingly at odds, but not hopelessly so. The independent artist aims to free their unique and particular voice and distribute their work. That work might be at odds with that which is meant to pacify, soothe, beautify, or conscript, but instead might be uneasy, complicated, or non-instantaneous. That work is, all the same, submitted to the feed with the risk of being overlooked or deprioritized. Artists, in all circumstances, as models and those refusing to act as such, are in a tricky position, one that is increasingly challenging to hold as rents rise and the standards for appearing in public life (or for being considered worthy of attention) are increasingly physical and expensive.

It seems the charge of artists and critical thinkers is to disrupt images, official narratives, and the justifications of power manifesting as physical or stylistic prowess that all maintain the status quo.

We enjoy models. We need models. The model is an artist in their own right, and the artist is a model. But we must inspect the politics of these acts.

We need new models for new pleasures in new ways. For all the new ethnicities and new body shapes (though I’m so glad to see these worlds expanding daily), there is deep neoliberal trickery at play. For all of those gorgeous, smiling, ecstatic, and exalted models, there are many extremely ugly things that are being sold: factory workers who are paid slave wages, a textile waste crisis that is offloaded to other countries so that the West can continue consuming at breakneck pace, technology and jewelry that depend on dangerous mining or child labor, human workers expected to work like machines in fields to produce even the most supposedly ethical of our foods. This understanding, the act of supporting this sort of economy, cannot bring ecstasy, that deep erotic fulfillment, that singularity of self and satisfaction to the model as their moment of hashtagging #BlackLivesMatter.

We need new models for new habits. If we wish to see a less fascist world, we’ll need models for the discrete actions that give way to that world, and we’ll need to see these new models living in some measure of proximity to ecstasy—real ecstasy contextualized in environments and sets that illustrate the world of our dreams as well.

This means an ecstasy that does not depend on ignorance of the supply chain, or temporary celebration of some community who has recently revealed themself as not just an oppressed minority, but also a captive consumer base.

We need models for what it looks like to engage in a deep conversation. We need models for what it looks like to clear a day, irrespective of the pressures of what could more flashily earned or achieved or performed in twenty-four hours. (We need to see the model choosing a different kind of deep mental work over portraying the work of earning, socializing for fun and jockeying for positions in a coveted social strata, or the very basic “I’m wearing this designer outfit to this party with these fellow celebrities.”) We need to see models take the time to hold two texts together, relishing in the pleasure of juxtaposition, navigating with their own experience and thought and relevant knowledge of how to compromise or synthesize what becomes of the contrast. We need models for what happens when these conclusions are uneasy, when we must pursue even more study, and more cleared days and more books strewn about, notes at the ready, post-its flagging places to revisit. We need models for how to make sense of what is read, the notes we took, the marginalia, the conceptual maps. We need models getting on interactive video, or IG Live, engaging with community about what they just read, co-processing with other models, say, artists and intellectuals of different professional fields.

“We need new models for new habits. If we wish to see a less fascist world, we’ll need models for the discrete actions that give way to that world, and we’ll need to see these new models living in some measure of proximity to ecstasy—real ecstasy contextualized in environments and sets that illustrate the world of our dreams as well.”

We need models for how to develop one’s own theory and praxis, models who contribute an adequate portion of their earnings to mutual aid campaigns. We need models for public service within the collapse of social institutions, and frankly, we need them to look good: just as good as the girls who are selling us stuff. And to that end, professionals concerned with beauty and art, artists, including commercial artists, or creators worth their salt, stylists, HMUAs, creative directors, set designers, who would consider themselves anti-fascist might begin to think deeply about how their skills are being applied: toward a more or less ethical world. There is a neoconservative modeling movement that takes place on the knees of every blonde Fox News correspondent, strategically posed behind a desk with no frontal—a conscious and clever decision from showrunners and network executives. No doubt, the right is deeply invested in making sure that their messages are modeled, and made up—that the grift is well glamorized. And as much as the worlds of fashion and art and beauty would like to see themselves as progressive, we fail to bring the creative strengths of our trades to bear on behalf of our beliefs.

We need models who take us on months-long or even years-long journeys, holding our hand as they demonstrate how they are learning about abolition or Black liberation movements, how they are inspecting and relating and talking back to the easy hashtags.

We need models who narrate how they’re updating their professional practice to align more fully with their politics.

We need models who are boycotting problematic brands with questionable ethics.

We need models applying themselves to non-profit work, applying their explicit talent to make cool to habits like reading, debating, and community service.

“Anti-fascism, for all its overlap with anti-materialism, needn’t resist beauty. Certainly, these spaces and their champions must be mindful of many deeper levels of what makes something beautiful (perhaps, that people were paid a living wage to make it). But why not don our best vintage, with a few ethically manufactured inclusions, put on our eyeliner not tested by animals, and make the movement sexy? As sexy, as erotic, as playful, and therefore, as meaningful, as possible. ”

We need models posed wretched and utterly discomforted at the pain of reading through George Jackson’s Blood in My Eye, describing how they will abstain from this year’s Victoria’s Secret Fashion Show as a protest against prison labor. We need models who are well-studied, well-read, utilizing their feats of beauty, composure and grace to relay ideas that are poorly tolerated when advocated by those comelier among us.

Anti-fascism, for all its overlap with anti-materialism, needn’t resist beauty. Certainly, these spaces and their champions must be mindful of many deeper levels of what makes something beautiful (perhaps, that people were paid a living wage to make it). But why not don our best vintage, with a few ethically manufactured inclusions, put on our eyeliner not tested by animals, and make the movement sexy? As sexy, as erotic, as playful, and therefore, as meaningful, as possible.

We need models who take on leadership in their fields of expertise (beauty, grace and glamour) to wrest the vocabulary of aesthetic gestures from their employers and appropriate them towards more mindful and ethical products and practices.

We need models who advocate for an idea of beauty that is not just performed by a more diverse array of bodies, but one that is rooted in the world that made the thing, in the politics of the product. We need models brave enough to test their strengths, making long-term consistent and concerted efforts to integrate our understanding of pleasure and ecstasy in deeper values. To invest wholeheartedly as they might in creating beautiful images for their portfolio in service of careerism, as for the movements they believe in.

We need models to think transparently and critically about how their bodies and performances are utilized. What if we were aesthetically stimulated by the joy of others not suffering in producing the things we wear and own? What if we took pleasure in not causing others pain the world over when buying our smartphones and diamonds? We need models that martial all of that sex and sensuality that paid off in the underwear campaign, to do the same for anti-fascist sentiments. We need models who will leverage their specific gifts to make anti-fascism sensual, erotic, and a place of pleasure. To recognize that their beauty is aesthetic power is moral power—and that in redefining what beauty looks like, we change the models of morals we might adopt. We find ourselves in an odd and inviting entanglement with modeling: the moment whereby our bodies rest or work or think or sell at the touch of fingertips, we are so frequently seeing and seen, the opportunity to be desired and desiring, at once, the chance at ecstasy.

But what is to come of it? We might buy a new this or that, but we might also begin to see remodelings, modelings that aim to coerce us towards our more noble ambitions of selfhood.

We need models for thinking and acting as our higher selves, not just our cooler and better dressed selves—our more literate, ethical, and intellectual selves as well.

We give life to a new idea and breathe easier in our new world where such togetherness and logic and the pleasure of its aftermath are infinitely possible.