noting the body in motion

Memories, like dreams, are models for the nervous system. They are their own archive living in the body, against the world, against the oppressive spheres, against the heavy winter skies a Berlin day sinks into, against fire the sun sets in forests and deserts, against a chanting pack of coyotes provoking divination at a distance. Memories are stored in bodies, archiving attunements, influencing dreams, charging the body politic’s output.

Bodies are memories in motion. Bodies are dreaming in passing. Bodies are archives that meander. The epigenetic make up, what we inherit ancestrally and from our mothers, is a paradigm the body is continually responding to and being shaped by. It is a model the body is filtered through. A body is an effigy for identity, intergenerational sharing, dreaming, and even grief. Bodies are archives that meander. Bodies hold memory. Bodies are memory.

My sister left when I was five. For years, we shared a bed, a room, a life. She raised me until she went away. She taught me how to brush my teeth, and she braided my hair, and she potty-trained me. She was eleven when I was born. I don’t remember her leaving. Something happens to the body when a severance occurs. A body torn apart. A rupture. A memory fractured and then unreachable. I woke up to an empty room. I was five.

For the first five years of my life, I only knew her as my mother. A girl walking in the shadow of a mother we shared. A girl in her own transforming body. A girl who bleeds. A girl, a miracle. And a mother bound by too many burdens. A mother whose pelvis bones separated twice in giving birth, whose abdomen was cut in an emergency C-section, once for my brother, a second time for me. A mother, a miracle.

The nervous system contains two subsidiary structures, the central and the peripheral. The central nervous system regulates bodily processes such as blood pressure, and the peripheral regulates sensory neurons. The latter is a somatic system that allows the body to sensate its surrounding environment through the five senses. In this way, the peripheral nervous system connects perception with action, resulting in instances of memory. One can theorize that it is in the peripheral nervous system that somatically driven responses to trauma, like the feeling upon waking up to an empty room, or body memory, reside.

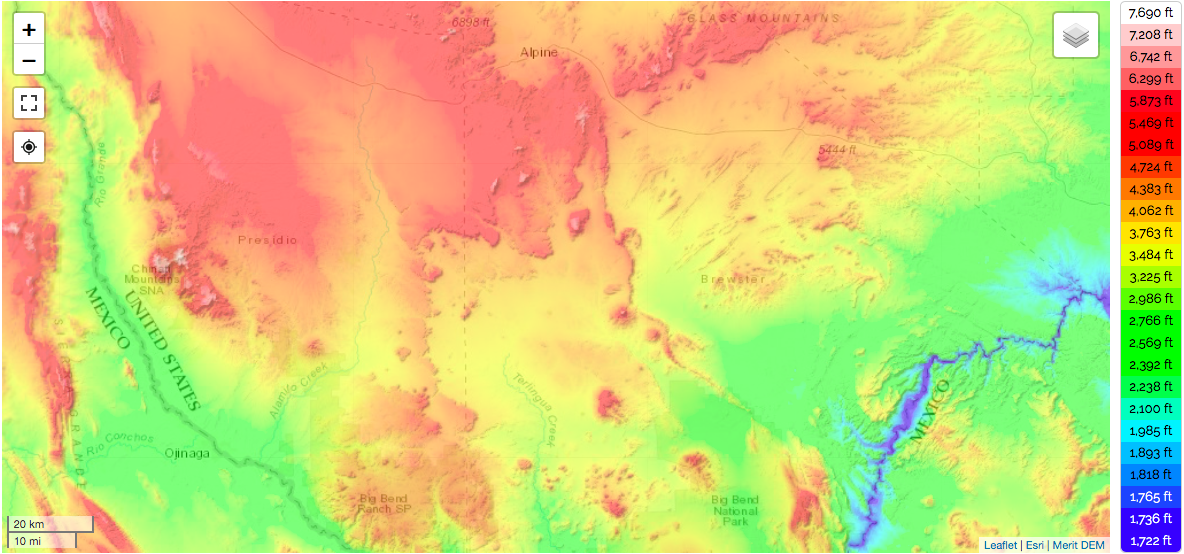

I was a child born into a desert wind, a border town, Terlingua, TX — what Gloria Anzaldúa calls “the borderlands,” where one [mestiza] is at home while also existing as a stranger. There was nobody around. Just trailers that punctuated the permeable igneous rock. Ash grays and muted reds, from crimson to chili pepper, the ground transforms everyday. Roadrunners followed the rhythm of the up-and-down highway hills, for many distances. My mama’s favorite bird. The medicine bird. The protector. The one that wards off evil. And there was that sky. Unforgiving in thunder and blitz. A rain that exhaled in release. And then the relentless dry wind, chapped lips and baked skin.

My parents told me that people drove for miles to the hospital at the announcement of my birth. My father arrived to meet me for the first time, and asked the nurse, “Who are all these people holding my daughter?” The nurse replied, “The surrounding towns!”

“I was a child born into a desert wind, a border town, Terlingua, TX — what Gloria Anzaldúa calls “the borderlands,” where one [mestiza] is at home while also existing as a stranger. There was nobody around. Just trailers that punctuated the permeable igneous rock. Ash grays and muted reds, from crimson to chili pepper, the ground transforms everyday. Roadrunners followed the rhythm of the up-and-down highway hills, for many distances. My mama’s favorite bird. The medicine bird. The protector. The one that wards off evil. And there was that sky. Unforgiving in thunder and blitz. A rain that exhaled in release. And then the relentless dry wind, chapped lips and baked skin.”

Body memory is a kind of memory that creates a corporeal narrative, a narrative the body writes when remembering or calling upon an imagination, a fantasy, or even having a dream. The body writes its own memory which creates its own story, as lived in the body. This corporeal narrative is encrypted as (body) memory which is rooted in facts, experiences, fantasies or even dreaming. Body memory is known as implicit memory, which is categorized into two different groups of memories: the emotional and the procedural.

After my sister left, my body forgot most things. The room was stripped of that feminine feeling at her departure. In the five years of sister-mother-hood I spent with her, I wore dresses, my hair in full-bodied curls, my fingernails painted. I remember crying the first time she put mascara on my eyelashes. Bodies are formed by spaces, as plastic is melted to take on the hardened shape of a bottle; the body is multiplied, transfixed, deconstructed, and reconfigured according to the spaces it dwells within or moves about. I was in a body unknown to myself. I was five.

Implicit memories differ from episodic and declarative memories, which belong to the category of explicit memories. In short, explicit memories are conscious memories that are labeled as either declarative (factual) or episodic (imaginative). Declarative memories are detailed and orderly, such as one’s grocery list or a favorite recipe: like remembering my mother’s favorite foods every time I taste red chile, because she added red chile to everything. And episodic memories are more feelings-based and dream-like, such as the retelling of a “feel-good” story; the first time a person falls in love, a graduation, weddings: like remembering the feeling of my mother’s voice soothe me into a sleep.

I started to sleep on the floor next to my mom’s side of the bed because my own room felt too big, too empty for me. Mama’s hand lowered to the end of the bed frame to hold my tiny fingers lifting above my head. Or sometimes she would sit with me in my bed, caressing my face with her finger tips. She would sing the Mockingbird song while her dainty, slim hands empathetically soothed the structure of my face until I fell asleep. Sometimes her hair would cling to my face and tickle me into a sneeze. She would say, “It just loves you so much.” Her hair, long and strong. I always looked up to it. Sometimes she would have one braid that hit below her hips. Measured my small body against her hair.

“Mom, I think I got taller,” I would confirm standing beside her like a yardstick, where her hair ravened like a river down her back. She was so petite. So beautiful. So gentle. And the ideal of what I was supposed to look like. I fantasized that I’d grow into her frame, to feather outward elegantly, to have her delicate fingers, her wide hips and curves, her slender arms and beautiful smile. To bloom accordingly.

Both declarative memory and episodic memory belong to the category of explicit memory, which is established more consciously. Implicit memories, however, are located on the other end of the consciousness spectrum. When locating these types of memories, the least amount of consciousness is activated. Emotional memories are corporeally illustrated through physical sensation. And procedural memories draw from this physical sensation and create or are a part of the corporeal narrative, a story of memories wrapped within the body, which can be exposed in dreams, a form of intergenerational sharing.

“And like memories, as the body is an archive of memories, one that holds the intergenerational make-up of our mothers, our ancestors, it also holds space for dreaming, invites our ancestors to visitations and prophecy, and protection. Dreams we choose to share with our future ancestors, as a form of resistance and sacred-sharing.”

Dreams are a bridge between physical and spiritual reality. They have prophetic power, transformative insight. Dreams, for me, are models to follow for foresight, caution, for divination, for rooting or even moving away from something. Dreams are sacred. And like memories, as the body is an archive of memories, one that holds the intergenerational make-up of our mothers, our ancestors, it also holds space for dreaming, invites our ancestors to visitations and prophecy, and protection. Dreams we choose to share with our future ancestors, as a form of resistance and sacred-sharing.

I don’t remember most things between the ages of six and ten. I can only recall some moments of feeling or affect. In my sister’s absence, I felt the world with closed eyes, eyelashes to cheekbones, hands out and navigating. I started wearing my brother’s clothes. Oversized shirts and baggy pants. It just felt right. I would open their wardrobe and dig until I found something that felt like home, something that didn’t cling to my body, didn’t ask me to be like the magazines, but just left me alone. There was one shirt I often returned to, a ‘Sting’ shirt with a large bee on the front, colored in army green. When I look at the pictures from that time, I feel a sense of comfort being braided into me, through me.

The first kind of procedural memory is learned motor actions, which is associated with physical skills, such as biking or ballet dancing. When I was younger, I took ballet classes and was scolded by the teacher for having legs that were ‘too strong.’ She often told me to glide with my toes, not with my legs. She told me I needed to stick to biking, not ballet, but I did both. I wanted to be dainty like mama, but have the fierceness I felt necessary to move through the world feeling different, or alone.

The next kind of procedural memory is known as emergency response, which is also known as fight or flight or survival mode. The person experiencing this memory is forced to rearticulate the threat (to fly, or flee the situation). Maybe this was my turning to my brother’s clothes. Maybe this was forgetting nearly four years of my childhood. I did have a best friend named Stephen. We were the same age. He lived two houses down from me. We built mud forts and played in the streams. I was leaning into a framelessness from the gendered body, and more into feeling a sense of togetherness or bestfriendship, like returning to mud to forget the body. A kind of bestfriendship that was missing between my sister’s absence and the idealization yet estrangement I felt with mama.The one who everyone said looked like Cher. The one who I could not match.

The third category is referred to using the following terms: approach or avoidance, or attraction, or repulsion. The third category of terms are indicated through movement. These movements are processes of the body. Mama and I cleaned the house together. She would blast Cher on the stereo and we would dance, sweeping floors and dusting. Me in my baggy clothes and her, swaying behind her long hair, like a curtain before her face, with her smile, shouting, “Do you believe in life after love?” I wanted to be more like her. To dance more like her. My tiny frame floating in my brother’s clothes, moving my hips back and forth, watching my hair swing like mama’s. A small figure, outlined in “boyhood.”

One’s patterns of movement hinge on their navigation around or within memories. The person may avoid certain smells that remind them of an ex-partner for example; they retract. On the other hand, a person may be attracted to and, then approach scents that remind them of someone they miss.

Mama’s favorite scent was lilac. Her favorite color, purple. But she told me that when she was younger, she always wore patchouli and sandalwood. I started wearing both in high school. When I traveled to Panama in 2006, I bought a small bottle of sandalwood. I still have it today, and wear it in the summer so my pores soak it in mid-summer heat, and I feel closer to mama.

On my tenth birthday, my sister reappeared. I believe she was in and out before that, but I cannot remember those exact details. I just feel it in my body. Like a rush of cold wind on top of a Colorado mountain. We have a picture together of that day, five years later. She’s sitting in the passenger seat of her car door, red-lipped, white scrunchie with a pony right on top, smiling. I am sitting on her lap, unbearably happy, comfortable, home again, wearing an oversized purple t-shirt and baggy jeans, a mouth full of teeth fighting for space to shine. Untouchable warmth.

Both avoidance and approaching gestures against / towards something in relation to a memory are often unconscious signals coming from within the body.

These memories are known as or applied to the notion of body memory, because they are contingent upon the body’s experience in the world, and often are exposed in unison with trauma.

“After spreading her ashes, my oldest brother walked down into the river. I, of course, followed. My feet pushing through branches and mountain mud, sinking into deep earth and reaching the water. It glistened, and I wanted her grace to hit me in my chest like an arrow. Wading in the river, I cleansed myself in the river and I let mama wash over me, braiding her memory, her grace, into me.”

When mama got sick with dementia, I was in grad school. And then, I was living in Seattle. My sister called me, “Tiara, you have to come back home now.” After a twenty-plus-hour bus ride from Seattle to Denver, I arrived at a house full of my siblings, their partners, their kids, and mama. Still her petite frame, still her long beautiful hair, but different.

I danced. A lot. The only way I was able to hold space for her or myself, or my sister, was to dance. In the midst of starting my PhD, I was dancing during the day, holding mama’s hands tight and laughing (grieving) with her. How perhaps the distortion of my body, in these moments, to lurch against or with the feeling of her becoming in contrast to my grieving. Her sorcery, transforming. My legacy, shapeshifting. My sister and I braided her hair. We sang to her. And we danced with her. My sister, her caretaker, her nurse, her everything.

Procedural memories are held and charged within the corporeal memory archive. And so they are illustrated as unconscious sensations in response to these memories or feelings, such as dreams.

My mama passed on December 24, 2020 at 2:22 AM, after six years of battling dementia. The suffering she experienced was only a chip of the pain I could endure at witnessing her journey. A loss my siblings and I sunk with and into. The last time I saw her was in October of 2019. I was kneeling next to her bed at the memory care clinic, gazing at her hands. I listened to her breath. I held her hands and I grieved.

June 2021, my siblings and I hiked her ashes up Longs Peak. It was mama’s wish, her sorcery, her legacy to root there. We hiked until we heard the water, the right water, the waterfall. My sister initiated a tobacco ceremony, a ceremony of gratitude, receiving and release. We all had our time with mama. After spreading her ashes, my oldest brother walked down into the river. I, of course, followed. My feet pushing through branches and mountain mud, sinking into deep earth and reaching the water. It glistened, and I wanted her grace to hit me in my chest like an arrow. Wading in the river, I cleansed myself in the river and I let mama wash over me, braiding her memory, her grace, into me.

One month after mama passed, I started dreaming about her. I had this dream and I wrote about it to my tarot reader, my divination sister. I returned to my email to find it:

My partner and I were at my abuela’s casa. I was still grieving. We were holding each other, laying on the couch in a separate room. I, crying in my partner’s arms, said, “I will never take a moment for granted with you. I will touch you and hold you and love you any chance I have because mama is gone and I regret not holding her hand enough or combing her long black hair, or holding her in the kitchen when she taught me to dance and to cook, to bake and to exhale.”

The television was on silent but the pictures lit up the room. It felt like 2 AM. I rose from the couch after saying this and walked into the kitchen and mama was there. And I, hysterical, exclaimed to her, “Mama, how are you here? I am so happy to see you.” She was sitting on a barstool at the kitchen island. Only the skylight, full with the moon, lit up the space.

The television was on silent but the pictures lit up the room. It felt like 2 AM. I rose from the couch after saying this and walked into the kitchen and mama was there. And I, hysterical, exclaimed to her, “Mama, how are you here? I am so happy to see you.” She was sitting on a barstool at the kitchen island. Only the skylight, full with the moon, lit up the space.

And you [my tarot card reader] appeared in the doorway, with joy and such a smile to see us together. You said you pulled a couple of tarot cards for me. And you were holding them up right and facing me, in your palms. You said, “Look, you have two pentacles. One is the ace of pentacles and the other is three of pentacles.” And after you said this, I looked back to my mama and I inhaled all I could in, and I woke up wailing in my partner’s arms.

And now, a year after her passing, I yearn for her to enter my dreams all the time, for dances, hand-holding, and to receive more of her. That beauty. That gentleness. That grace. How, even now, as I sit writing, holding part of her braid, which smells exactly like mama, in my hand, I still ache to be more like her.

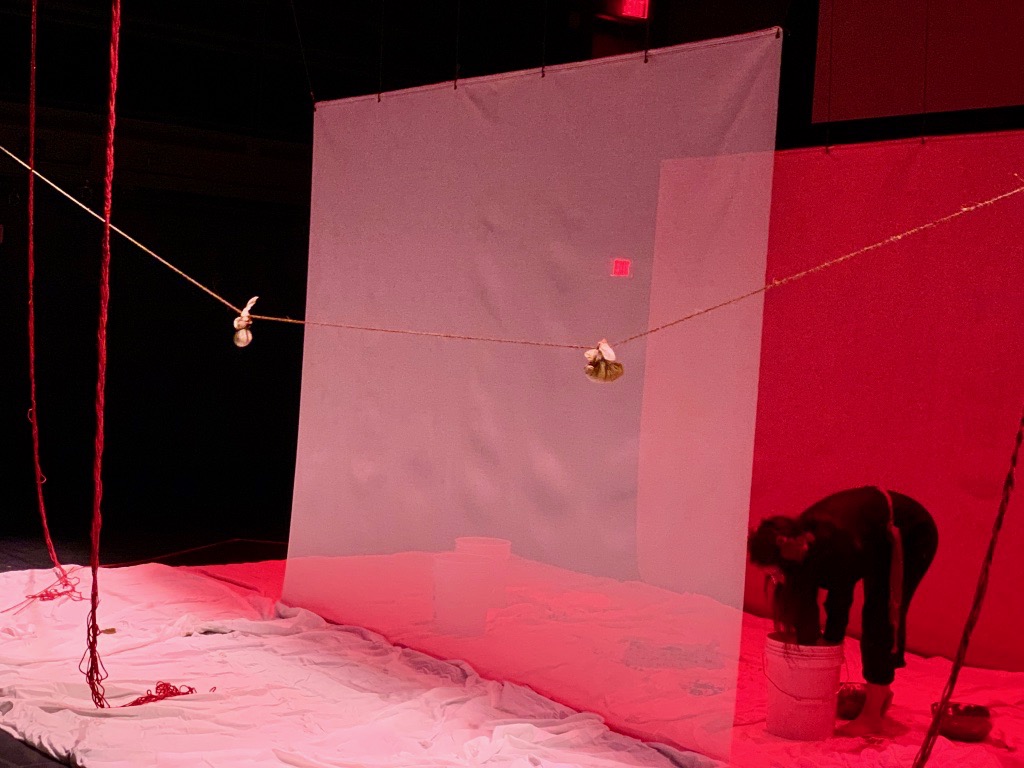

Tiara Roxanne (PhD) is an Indigenous mestiza based in Berlin. As a scholar and researcher, her practice investigates the encounter between the Indigenous Body and AI by interrogating colonial structures embedded within machine learning systems. In her performance art, with her body at the center, she works between the digital and the material using textile. Currently her work is mediated through the color red. Tiara has presented her work at Images Festival (Toronto), Squeaky Wheel Film and Media Art Center (NY), Trinity Square Video (Toronto), SOAS (London), SLU (Madrid), Transmediale (Berlin), Duke University (NC), European Media Art Festival (Osnabrück), re:publica (Berlin), University of Applied Arts (Vienna), Tech Open Air (Berlin), Zurich University of the Arts (Zurich), AMOQA (Athens), CTM (Berlin), among others.