No Beginning and No End: Megumi Shauna Arai in Conversation with Hannah Martin

When I saw a nineteenth-century chalk drawing at a museum in London last October, it reminded me of my friend Megumi Shauna Arai’s fabric paintings. I sent her a snapshot. Titled Study of Drapery, by Victorian painter Frederic Leighton, it depicted what looked like a floating, disembodied garment. “The exact inspiration for my spring show,” she texted back, explaining that these studies often left negative space or emptiness where the body belonged, in preparation for larger paintings.

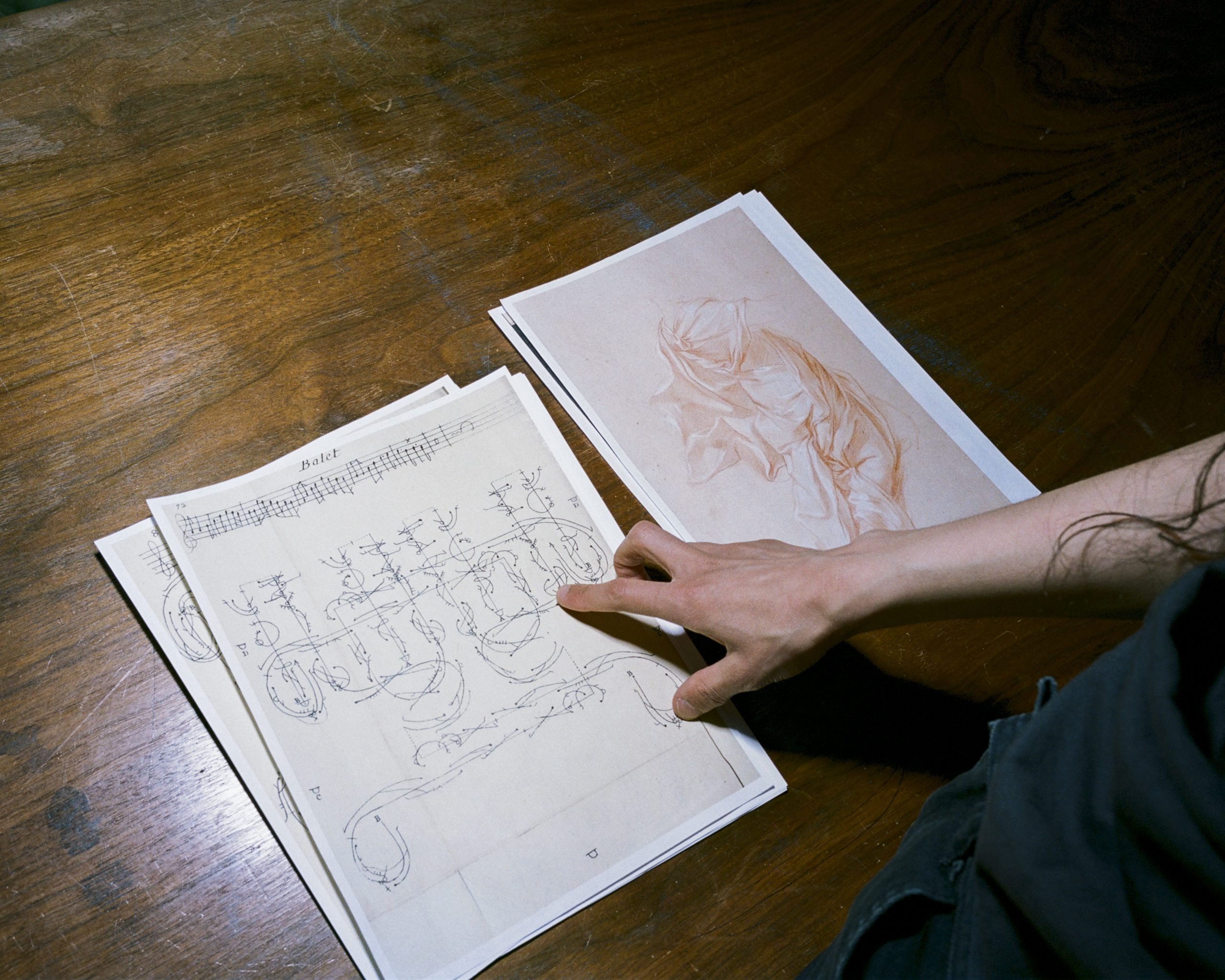

Six months later, I sat down with Megumi to dig into the details of said solo show, Immanent Infinite, which opened April 29 with Object & Thing at Makié Creative Space in New York City. We looked at books and reference imagery in her Lower East Side studio, nerding out about her influences: Aby Warburg’s concept of Pathosformel, Gilles Deleuze, contemporary feminist writers like Laura U. Marks, the Buddhist practices that inform her work and life. They all find their way into her pieces, which portray emotion and being through something we see every day, hanging on a laundry line or draped around a body: fabric in motion.

Hannah Martin: We’ve been discussing this show in bits and pieces for a while, but I’m excited to really get into it. What is the essential idea behind this new body of work?

Megumi Shauna Arai: Simply put, it’s about the relationship between fabric and movement. There are three main types of work in the show: an ongoing series of large, folded silk pieces, a series of textile resist paintings, and two video pieces, created in collaboration with a dance artist, that are presented as a prologue and epilogue, a bit like in a piece of literature. Each one is an iteration or a translation of the next, creating a sort of circle. So there’s no beginning or end.

You had a kind of epiphany at the Uffizi while at a residency in Italy two Septembers ago. Can you retell that story for dramatic effect?

I’m not Christian. I’m mixed. Growing up non-white and part-Jewish in the United States, I felt like a lot of Judeo-Christian stuff was shoved down my throat. The canon of art history replicates this, too—there’s so much Christian iconography in the Old Master paintings. As a working artist, I’ve always wanted to think about everything other than that. But when I took the obligatory walk through the Uffizi while in Tuscany with my partner, Josiah, I found myself standing in front of some of these paintings and I was just like, “this is undeniably moving me. I can’t stop looking at this. I’m having so many emotions.” I was shocked. Something about Botticelli in particular, the way that he painted drapery off the body, the folds and movement of fabric: my jaw was just like—boom—on the ground.

There was a small special exhibition about Aby Warberg’s work on movement and Renaissance painting. He coined the term Pathosformel, which is, essentially, an emotionally charged visual trope, like the representation of movement in the folds of fabric. This was a major “aha!” moment for me. I had already started working with folded silk in 2022 and I really wanted to capture this emotive quality of fabric in motion. I was like, “man, this is what I’ve been trying to talk about,” these emotions that are welling up inside of me when I look at these painted depictions of folded fabric.

I remember seeing you after that trip. It had really crystallized something for you. So much of Warburg’s writing focuses on a body being in that garment. But in your work, the body is usually absent. How do you reconcile that?

Reading about Warburg sent me on a deep dive of looking at the representation of fabric in Old Master paintings. It’s a character in itself; it represents a vast spectrum of states of being and emotion. Before painting, these artists would engage in a practice of drawing the folded fabric first.

Without the body.

Folded fabric was often the most complex to paint. Some art historians argue that this was one of the earliest forms of abstraction in the western tradition. It was also a place of freedom, where artists could be the most creative.

When we first met in 2020, patchwork was a big part—or should I say, a more visible part—of your practice.

Textile—and patchwork specifically—is ingrained in this communal practice, sitting together slowly working and talking. In so many cultures, it’s the glue of a community. Patchwork and quilting are also early examples of abstraction, whether you’re looking at boro from Japan or Gee’s Bend quilts.

In this show, you’re incorporating and abstracting dance notations. Can you tell me a little more about this?

During my library residency last summer at the Cooper Hewitt, I spent a lot of time with the first edition of Denis Diderot’s Encyclopédie. What blew my mind was the choreography section—these symbols that were part of a notation system called Beauchamp-Feuillet, which was, essentially, a Baroque-era dance notation. They were translating movement into symbols in order to create dance.

They were taking movement and turning it into symbology. How does this connect back to your thinking around abstraction?

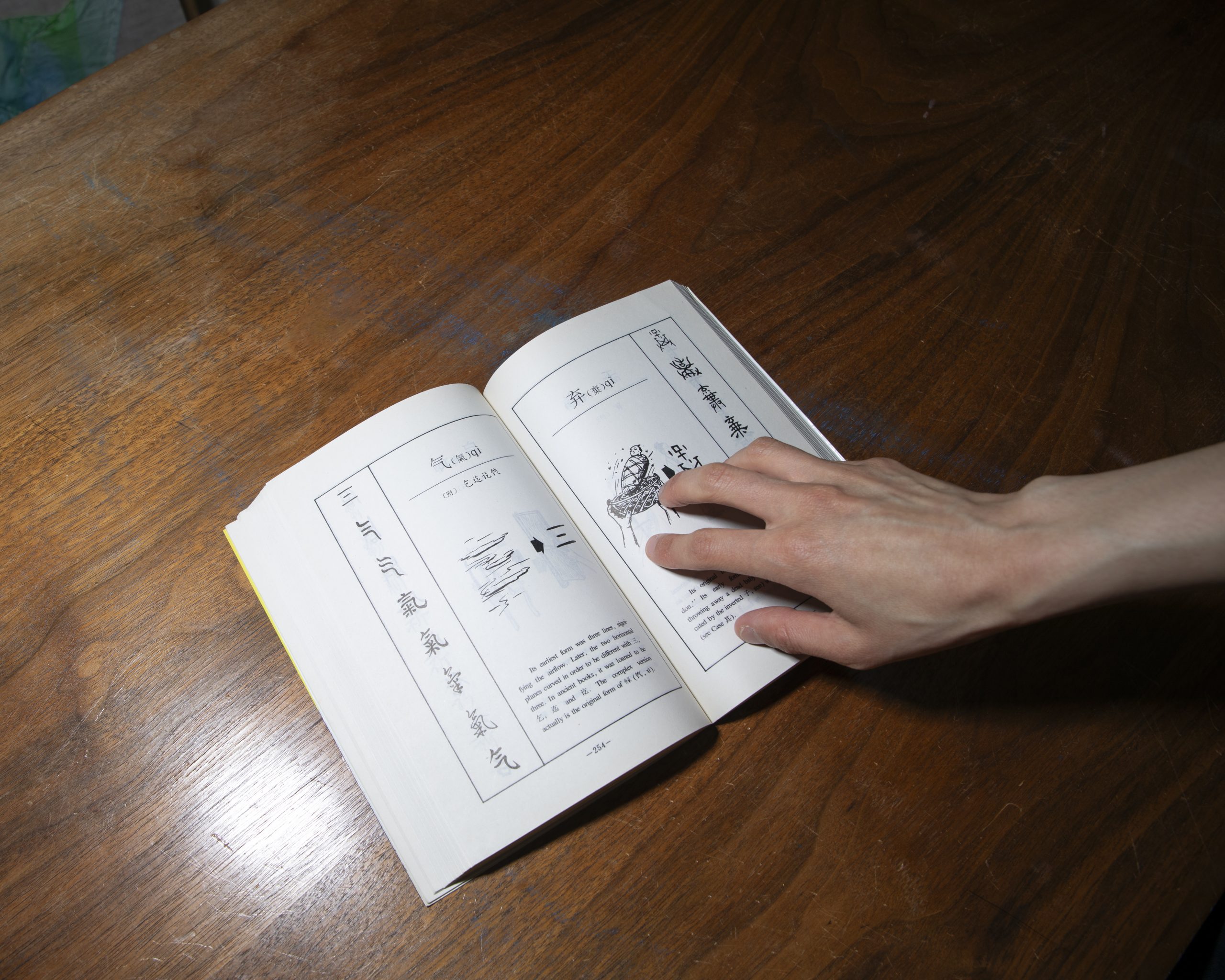

I’m very interested in a history of abstraction that was happening hundreds of years before Abstract Expressionism. Abstraction was not a western invention. And these symbols from the dance notations were reminiscent of Islamic and East Asian calligraphic traditions. So this other series of work is inspired by both dance notation, and the origins of Japanese calligraphic text, specifically Oracle Bone Script, which is the earliest known form of Chinese writing, and other Chinese pictograms. The examples that were most inspiring to me were actually drawings of movement.

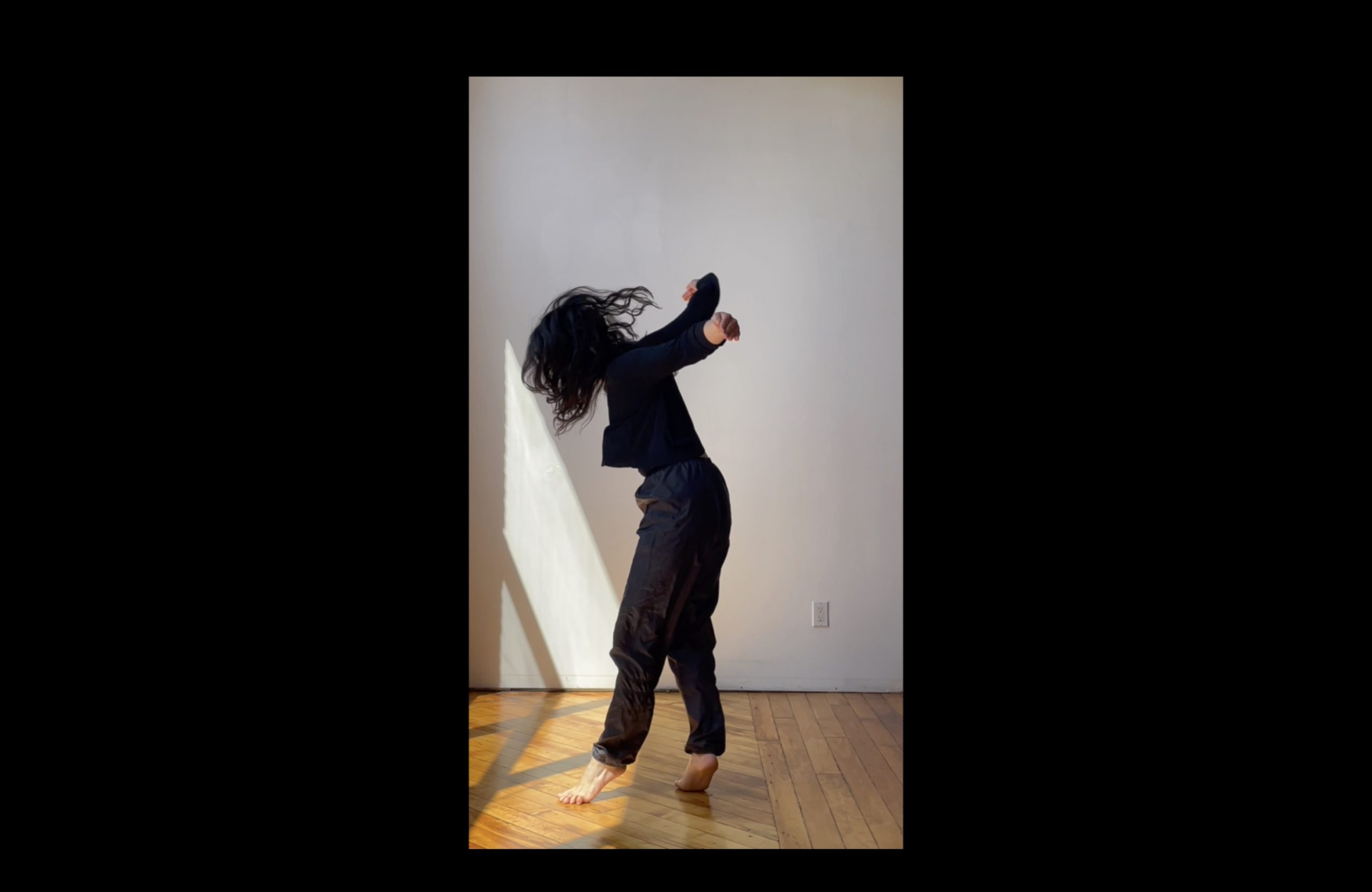

You introduce an actual human body into the mix with these video works, where you collaborate with dancer Ayano Elson. How did that unfold?

She has interpreted the three works that are inspired by dance notation. Essentially, she’s dancing the paintings in repetition over and over again. We walked through and created a map of how I wanted to film, the rhythm, how we would proceed. She did not see the work until the day of—it was an improvisatory translation.

What was she wearing?

The most nondescript black outfit. The whole point is that it’s just the body. Elsewhere in the show, fabric and movement is present, but the body is absent; in the video, the body is present, but the expression of the folded fabric is absent.

What is it about folded fabric that has such a hold on you?

There is something about the way that fabric folds that is a way of thinking about life. It’s essentially metaphysics through folded fabric. (Laughs.) It’s nonlinear, it’s fluid. Everything that is unseen or unknowable on the surface is actually what makes the surface.

“There is something about the way that fabric folds that is a way of thinking about life. It’s essentially metaphysics through folded fabric. It’s nonlinear, it’s fluid. Everything that is unseen or unknowable on the surface is actually what makes the surface.”

This book you’re reading feels pretty relevant to those ideas: Laura U. Marks’s The Fold: From Your Body to the Cosmos.

So much of continental philosophy is devoid of day-to-day living, breathing life. She really makes Deleuze more relatable to the real world. I’ve always been interested in metaphysics. It’s actually what I first went to Bennington to study, but I was very discouraged and overwhelmed by being in a room and a department that was all white men. But the more I make things, the more I can choose to do that learning and reading that has always interested me, and include it in my work. I’m thinking about folds as a critical way of engaging with the world: it’s always in a state of becoming. And that really connects back to me being a Buddhist.

What does your Buddhism practice look like these days?

I meditate. I need meditation because I am not serene. My Buddhist-leaning spirituality and Zen predilection has been there a long time. I got sober in 2010. In getting there, it really helped me to think of something greater than myself. I needed to expand my perspective, to think about the world or existence through geologic time, not just seeing what can be a very immediate and small world and life in the twenty-first century capitalist grind.

So how does all of that translate into your actual process of making? How do you bottle that and also organize it all so that you can ultimately create your work?

Really, it’s about holding both the order and chaos at the same time, and just really intuitively being led by those two energies. I would say I’m the most ordered mess ever. I generally do have a pretty distinct plan in my mind. I have a roadmap, but then I allow myself to really just run off the road.

Recently, I’ve been thinking a lot about how being slow in general is becoming an almost radical act. Your process is very repetitive and slow—a lot of days you’re just stitching in total silence. You don’t even have a window in here. Do you think of it as a durational practice?

I’ve always been this way. When I was younger, it was something I actually kind of hated about myself. But then as an adult, I became more aware that society’s emphasis on productivity is tied to capitalism. As the years have gone by, I’ve come to really love this about myself. It’s a way of moving through the world that I really believe in.

You’re a self-taught artist. How did you first start practicing?

I always wanted to make things. We lived on the outskirts of Tokyo when I was nine years old. Every week I would ride my bike across the river to take lessons with a private oil painting teacher at her really serene house, with a beautiful garden full of roses. She made me draw lines forever. It took me months to even be allowed to hold a paintbrush.

I’ve also always been obsessed with fiber. As a teenager, I got a spinning wheel for my birthday. I would buy giant bags of washed and carded roving. There was no rhyme or reason or end product: I was just obsessed with the experience of having this soft, beautiful material that I would hold and slowly feed into this rotating, rolling, spinning wheel. It really soothed me. I’ve always moved through the world and processed information, knowledge, ideas, and experiences through being a maker.

You’ve been able to develop work without a lot of the prescriptions that come along with going to art school. How do you think that has influenced your practice?

I see it as a superpower. When I had the opportunity to go back to school, I purposely chose to study sociology instead of art. I am very interested in cultural theory and how individuals are affected by these larger systems and histories.

How does social practice fit into that?

Teaching and community-oriented artmaking has always brought me such a sense of joy and purpose. My studio practice can be really isolating. I’m sitting here doing repetitive motions in silence. So it’s about creating a space where people can come and make together. I had a residency with the Lower Manhattan Cultural Council, where I was stitching and doing patchwork with elders in the East Village. I get to learn so much from the people who show up. I really believe everyone’s an artist.

The idea of “beginner’s mind” is a core tenet of Zen. How does that approach find its way into your work?

It’s related to coming back to the breath, coming back to the present moment. You’re letting go of ego or needing to be an expert. In a lot of ways, it’s about shedding all of the habits and structures we think we need to be a well-functioning person in the twenty-first century. A sense of awe comes as a result of a beginner’s mind. I’m so happy I get to live this way. If I am drawn to something, I just go for it. I just learn it. I put myself in positions to be in conversations and to read and to think. I’m always a beginner.

Immanent Infinite is on view at 109 Thompson Street through May 10. Special thanks to Object & Thing.

Megumi Shauna Arai (b. 1989) lives and works in New York City. Her work has been included in recent exhibitions: Group Shop Show, Bridget Donahue Gallery (2024); Summer Arrangement: Object & Thing at LongHouse (2023); The Third Kind, Management Gallery (2023); Object & Thing at Madoo: Megumi Shauna Arai and Frances Palmer (2022); At The Noyes House: Blum & Poe, Mendes Wood DM and Object & Thing (2020); Lore: Reimagined, Wing Luke Museum (2018); and Midst, Jacob Lawrence Gallery (2018). Recent residencies include Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Library; Headlands Center for the Arts, and Lower Manhattan Cultural Council. Alternative pedagogy teaching collaboration includes Field Meridians, an art-based urban ecology curriculum in Brooklyn, The Museum of Modern Art public program Family Festival: Another World, and The Mothership, an eco-feminist art and ecology center founded by Yto Barrada in Tangier, Morocco.

Hannah Martin is a New York-based editor and writer with a focus on modern and contemporary design, art, and architecture. She is the senior design editor at Architectural Digest and is the author of Nicola L.: Life and Art, the first comprehensive monograph about the pioneering French artist, published in 2023 by Apartamento.

Banner image: Megumi Shauna Arai in her Lower East Side studio with This Skein Becoming, 2025. Photograph by OK McCausland.