NEO-BODIES Breaks Down Prescriptive Notions of Coding Our External World

Here’s an image of a woman in a designer trench wearing a Seth Price FDIC-printed T-shirt. Her hair is down, clear skin, red lips parted to reveal good dental hygiene. The image is cropped above her mouth, her identity protected or at least not on the table in this social media equation. The setting is urban, there’s vegetation in the frame, could be Paris 4e or midtown NYC with a Phoebe Philo Céline vibe. She’s a particular woman,1 yet in this case—staging her own “Fuck Seth Price”-style meta quotation of what she appears to be—stands as 2016’s iteration of the Manhattanite female archetype; simultaneously forty years old and twenty-eight, penning personality profiles for Vanity Fair, Interview, Fantastic Man. You take her to be someone with cleanly waxed everythings and an Adderall prescription in her purse … who carries a purse, who owns multiple pairs of the kind of shoes that require taking cabs; who, when you say hello, smells like perfume, gum, alcohol, and dry cleaning. You get the sense that she’s in control of the intensities that run through her.

Every age has its own recipe of this body-subject (which might be taken as a kind of general ideal today)—as bodies are never precipitated out of a non-place. Neither are they ever merely the product of biology. They come into being, rather, as the net sum of one’s ideation-of-self plus coding-of-external-world. As Deleuze understood it, regarding the subject who refuses the sign of food, “Anorexia is a history of politics.” 2 To reject food as a sign, one must first give this food-sign a certain sign value. And the same could be said not only of other deprivation-based relations—the vegans and orthorexics who read their bodies as pure and the world as toxic—but also of those that are looking to “gain,” “bulk,” or “build,” those who code the world as abundant, their bodies exceptionally depleted. To set oneself in relation to this spectrum of need and self-reliance—the limits of what the body requires and of what the world can offer or is asking us to consume—is to draw borders, to build walls, and to designate regulated points of exchange. Per Deleuze again, “There is politics as soon as there is a continuum of intensities.”3

1. TOXIC

Feeling sluggish, the exec books a five-day cleanse. She reads through the BluePrint® profiles, settling on Excavation®: “a high-intensity level [cleanse] designed to flood your body with chlorophyll, restore alkaline balance, and dig deep.” For $325 she will have a work-week state of exception, allowing her cells the time to expel toxins as she segregates herself, her needs, her sleeping and eating cycles from her social and professional peers. Through this program of organic solids cold-pressed into liquids, she will be protected from pesticides and GMOs, but also from the social burden of interfacing with waiters, check-out clerks, and others she would normally come in contact with in order to eat. On the cleanse, food is simple, containing compatible ingredients that together form a palette of purity: green, white, and clear. There is no fusion, no ethnic branding, and everything is sourced from gardens and greenhouses far from the systemic edge. Divided into several bottles per day, the regimen is taken in doses, like Suboxone, each one calming the body’s central nervous system as the previous serving wears off. But not only is this a matter of regulating brain chemistry; also, in this, the food-capital relation is regulated, too. As the rules of this plan prohibit external eating, no additional money is spent on meals; so after transferring the initial fee, the cleanse is just there, ready for consumption. However, the juice’s “detoxifying” properties differentiate its sign value from “food” alone. Rather, it is coded as a substance of incalculable value, not unlike art, in its ability to allow one to interface with the world as separate from it, and superior to it: the juicing exec as Kierkegaardian aesthete, making the world a better place through her good-citizen investment in self-maintenance and newfound higher awareness of how little she actually needs.

2. CELLULAR CLEANSE

There has been a popular shift over the past decade or two in our understanding of the body’s functions and how we intervene in its processes. Perhaps nowhere is this more pronounced than via the (US American) pharmaceutical industry, which has produced a chemical fix for every micro imbalance for which a metric exists. Compare this, for a moment, to the practice of allowing the body to heal itself (from consumption, as it were) aided only by bedrest by the sea, or via the age-old cure of bloodletting, wherein the humours flow until stasis is restored. Bodies now are less mysterious vessels than aggregations of cells—cells that are at risk, we’re told, of being overloaded by “xenobiotics,” synthetically produced (or other external) chemicals that, given their molecular structure, plug into the receptors intended for those the body naturally generates. According to this image, sickness is caused by an onslaught of free radicals occupying the root of one’s life force. Further, the body is hereby placed at risk of dispersion into the (impure) world, wherein ostensibly it doesn’t stand a chance of surviving. To protect against these threats, pharmaceutical companies and their corporate naturopath counterparts (who, even if they manufacture and brand their products differently, tend to conceptualize sickness similarly) provide not “health care” but “cellular support.” “Flood your body with chlorophyll, restore alkaline balance, and dig deep.” The path to health, to transhumanism is (via the) molecular.

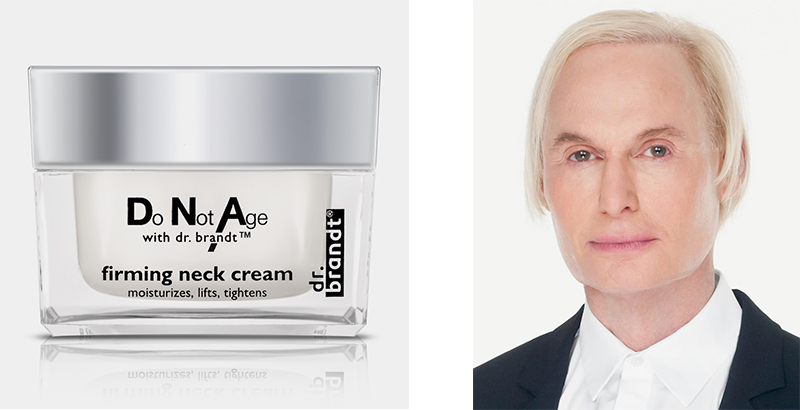

Recent trends in plastic surgery follow this same logic. Appearing in a short video introducing a new treatment his practice was offering shortly before his death last year, the New York dermatologist Fredric Brandt spoke of the benefits of injectable face filler as an alternative to the conventional cut-and-sew facelift. The body on its own will over time become corrupted, he explains. But decay can be stymied through “cellular nourishment and cleansing”; the face is rejuvenated and preserved through certain carefully administered foreign agents, namely: botulinum toxin, hyaluronic acids, and biosynthetic polymers. Perhaps this can help to explain why Caitlyn Jenner’s female-coded face and body, when it was unveiled, seemed somehow anachronistic despite the very current gender conversations to which it spoke. Not only was her physique crafted more in the image of a Baywatch-era Pamela Anderson (optimized for the male gaze) than, say, an empowered female post-Riot Grrrl, but her face, having decidedly been shaped by use of scalpel, recalled the striated, analogue processes of the pre-screenspace ’80s, a time when there was still an ideological outside and inside: the body as object to be externally adorned and costumed in Cartier and Lacroix. Now change is supposed to be gradual, the process smooth, like a background app refresh happening via zeros and ones, from the inside out rather than through mechanical intervention from the outside in.

3. BODY COMBAT

“Fitness is literally in our blood,” reads the Les Mills® “About us” page on the international fitness brand’s site. With names such as “Grit Plyo,” “Body Attack,” and “Body Combat,” the massively popular, high-intensity workout routines promise body transformation through sweat and pain, activating “fuel-hungry” muscle cells. First-timers to the program will soon find themselves to be “Les Mills addicts,” the site explains, “craving [their next session’s] neurochemical release.” Perhaps not contradictorily, the marketing copy pitches the program as essential to “achiev[ing] more at your desk.” And herein is Foucault’s “cultivation of the self”—or Socrates’s art of epimeleia heautou4—playing out in post-millennial terms.

“Taking care of oneself” has nearly always been a requirement in civil society, and certain status has always been accorded to individuals whose fitness level is high. What’s interesting here, though, is the current emphasis on intensity: one doesn’t sign up for a class, but for “boot camp,” as though a neoliberal soldier training for that moment in the boardroom when the jacket comes off and the sculpted upper arms are revealed: “I am a master of self-care,” that taut skin between armpit and shoulder says.

Consistent with fears of body permeability, neither is contemporary fitness confined to the gym. As a thousand think pieces must already exist on “control society” themes in body-tracking wearable tech, it suffices, here, to say that these bracelets operate not only to aid the wearer in tabulating their literal every step, but also in the act of demonstrating this awareness to others. The hedge fund manager reaches across the table at lunch for the sparkling water, flashing his Fitbit to the client after placing his order for steak frites; these calories are being consumed for you; in the cab back downtown he will be logging in the estimated nutritional intake of his meal, calibrating his workout plan for that night. Though something of a misnomer in the particular habitus invoked here, the use of wearable tech also implies the valuing of a “life outside of work”—a claim that is compromised when one considers that the evidence of succeeding in this “non-work” realm (e.g., the cut physique, the tan lines of outdoor leisure) is certainly as powerful an accessory in a corporate office context as any sartorial object that could be bought in the boutique. Cue Mark Zuckerberg speaking to his shareholders, his in-progress biceps filling out the circumference of his grey tee sleeve.

4. WHITE CASTLE

With this body/world landscape as backdrop, it’s tempting to accord extra meaning to Telfar’s recent, post-NYFW parties, which he held in a Midtown Manhattan White Castle. Video clips from the parties show not only platters full of the American burger chain’s fries and its “sliders” (which the green juice set may code as “toxic,” but technically offer a more efficient nutritional profile than BluePrint’s Cashew Milk, a staple of its Excavation cleanse)5—it also shows something that, in the context of this text, can best be described as liberated bodies: tattooed hands (i.e., hands permanently marked with the memory of a certain moment, rather than Fitbit’s perpetual surveillance of every second lived) holding jumbo cups of fountain soda and vodka; young millennial bodies, slender and a little soft, shaped by a diet of Tumblr, Haribo, and Xanax. The aforementioned bourgeois criteria—the (self) control, and coding of the self as contaminated by the external world, and fear of dispersion into it, of mixing with it—is, here, disavowed.

The recent emphasis on casting—particularly of less conventional, even comparatively unusual faces and bodies—among the more innovative fashion labels active now might be related here. With modeling firms such as Eva Gödel’s Tomorrow Is Another Day in Germany,6 or Lumpen agency in Russia, there is a growing demand in the industry for bodies that are beautiful without conforming (or precisely because they do not conform) to the same politics that produce the BluePrint body. One could say that the Lumpen runway model, like Marx’s lumpen, is one that resists isolation, individualism, competition. And indeed, its attraction lies, to at least some degree, in its sign value of non-competition. Also, there is the evocation of a vaguely post- Chernobyl, Soviet-era communism—a beauty that suggests a different place along the spectrum of self and outside world; bodies that aren’t threatened by toxins, but rather could even be seen as products of that contamination. This subject’s beauty cannot be reduced to an over-abundance of chlorophyll-enriched cells.

In a special formulation of “power to the people” meets “fuck the man,” the Telfar x White Castle double-marketing hack was more than just a successful exercise in commixing worlds. Perhaps the franchise manager put it best as he closed out the evening with a toast to Telfar and the last of the party’s crowd: “Tonight we stormed the castle walls.”

Caroline Busta is the editor-in-chief of Texte zur Kunst. Based in Berlin since 2014, she was previously an associate editor of Artforum magazine, and from 2006 to 2008, co-director of Miguel Abreu Gallery in New York. She has lectured and published catalogue essays on the work of artists such as Merlin Carpenter, Bernadette Corporation, and Bjarne Melgaard.

This essay first appeared in Texte zur Kunst, No. 102 (June 2016), “Fashion.”

NOTES

1. Photo is of Stephanie LaCava, whose forthcoming novella Superrational tells the story of a female cosmopolitan of the ilk described here.

2. Giles Deleuze and Claire Parnet, Dialogues, trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Barbara Habberjam (Columbia University Press: New York, 2002), 111.

3. Ibid.

4. Michel Foucault, “Cultivation of the Self,” in The History of Sexuality, Vol. 3: The Care of the Self, trans. Robert Hurley (Pantheon Books: New York, 1986), 43.

5. A White Castle Original Slider has 7 grams of protein, 6 grams of fat, and 1 gram of sugar for its 140 calories, thus technically offering a more efficient nutritional profile than a bottle of BluePrint’s Excavation cleanse Cashew Milk, which, for 300 calories, delivers 7 grams of protein, 19 grams of fat, and 21 grams of sugar.

6. The cover of Texte zur Kunst, No. 102 (in which this article first appeared) features Tomorrow Is Another Day model Roman Ole.