“Modern is How My Mother Made Me”: The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism

In her review of The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s recent exhibition The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism, writer Darla Migan enters the installation’s ambitious narrative by way of two artworks: William Henry Johnson’s Woman in Blue (1943) and Laura Wheeler Waring’s Girl with Pomegranate (1940). In these works, Migan finds reflections of her own girlhood—of the facial features she inherited from her West African father, as well as the lessons about composure and comportment she inherited from her West Indian mother. Turning her attention to the writings of the “New Negro” intellectuals who shepherded the Harlem Renaissance, and the art they inspired in turn, she considers the myriad tropes which have imbued and dissected black identities across the transatlantic diaspora. She asks: who did this movement intend to reach or include—and did they?

— Ebony L. Haynes, 2024 EIR

Two images circulated to advertise The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (February 25–July 28, 2024): a portrait by Laura Wheeler Waring titled Girl with Pomegranate (1940) and Woman in Blue (1943) by William Henry Johnson. A Black femme appears at the center of each painting. Waring paints in a style similar to her academically trained counterparts of the period. The girl, holding a bright red-orange fruit, wears a brown dress with a broad sailor-style collar and is seated at a small desk or table. Her posture brings back memories of my mother telling me to sit up straight. Her hair is oiled and styled with a center part, her visage relaxed yet also detached from the viewer’s gaze. A small canvas behind her implies that she might also be a practicing artist and not merely a prop, like the traditional still-life objects depicted in the background.

By contrast, Johnson’s visual vernacular renders a woman in a fitted, cap sleeve midnight-blue dress, showing off her curves. She is self-empowered; her face, defined by disc-shaped eyes and full lips, takes up one-third of the canvas, perhaps inspired by a Fon mask. Like Waring’s figure, she is seated—one arm crosses her waist with the crook of the opposing elbow resting cooly over the high back of a throne-like yellow chair. Her posture is informal yet still self-regarding; it is the cool decorum of energized repose. Johnson’s impasto style carefully structures the viewer’s own play with a host of quickly made associations. For example, the picture is as flat as the woman’s nose is broad, and at first glance, the yellow chair might resemble a saxophone. We could imagine her to be a musician on a break between sets, or even the Mistress of Ceremonies at a nightclub.

I see my own girlhood and womanhood represented in each of these paintings, both within and beyond the surface of the canvases. On my face many might recognize a nose familiar to the ethnic groups of West Africa. Yet I was raised by a strict West Indian mother whose disciplining cannot be separated from its colonizing influences, albeit applied for the sake of my own self-preservation. What I glean from my own upbringing and feel as I reflect upon both Waring and Johnson’s paintings is that, regardless of how each one of us has been taught to or is inspired to live, the planetary diversity of Blackness, as well as the spectrum of Black self-understanding, cannot be disentangled from our transatlantic modernity. The transatlantic fact of our modernity means that my immigrant family in the United States must have cousins and kin spread all over Europe and the Americas, many of whom are concentrated in the American South.

I inherited my bodily features, such as my skin tone and wide flat nose, from my West African father rather than my West Indian mother. On a recent trip to Paris with my mother, I made what I thought was a casual remark about seeing my Francophone father’s West African nose on the faces of metropolitan Parisians. My remark to my mother, now a multi-decade resident of suburban Atlanta, had to do with what she thought about the sale of people from the Kingdom of Dahomey, connecting us to Black diasporans everywhere. She responded with a silent avoidant shake of her head, signaling her disinterest in this particular conversation, and we continued on our way from Charles de Gaulle to begin her first tour of the City of Lights.

“What I glean from my own upbringing and feel as I reflect upon both Waring and Johnson’s paintings is that, regardless of how each one of us has been taught to or is inspired to live, the planetary diversity of Blackness, as well as the spectrum of Black self-understanding, cannot be disentangled from our transatlantic modernity.”

In that moment I was brought back to a childhood memory: sometime just before puberty, my mother told me to put a clothespin on my nose. This would have been when I was perhaps ten or eleven, a few years after my mother’s job relocated our family to Georgia from New York. This tortuous recommendation was intended to make my nose narrower, smaller, straighter, and more aquiline like her own. Over time, comments like these—about the shape of my nose or the bounty of my breasts, as well as the length of my skirts—shamed me but did not exactly hurt, since I did not (and still do not) see what could possibly be wrong with the face or the body I have been given.

How does one raise a Black girl child, given the legacies of dishonor our mothers have been subjected to for centuries? How was my mother raised by my grandmother, and she by her own mother (who I only heard remembered as Granny)? When my family made the move down South in the 1990s, my parents had no close relatives there. Thus, I was raised between multiple sites of interconnected yet disparate Black worlds. Certainly, I now understand that my mother, like most Black mothers, raised her children from the knowledge of the ongoing horrors of our racialized modernity. But rearing me on her own Caribbean heritage, and later doing her best to raise her children as a single divorced mother, her ways often felt odd or old-fashioned to me, a teenager growing up at the millennial turn in the ATL.

⁂

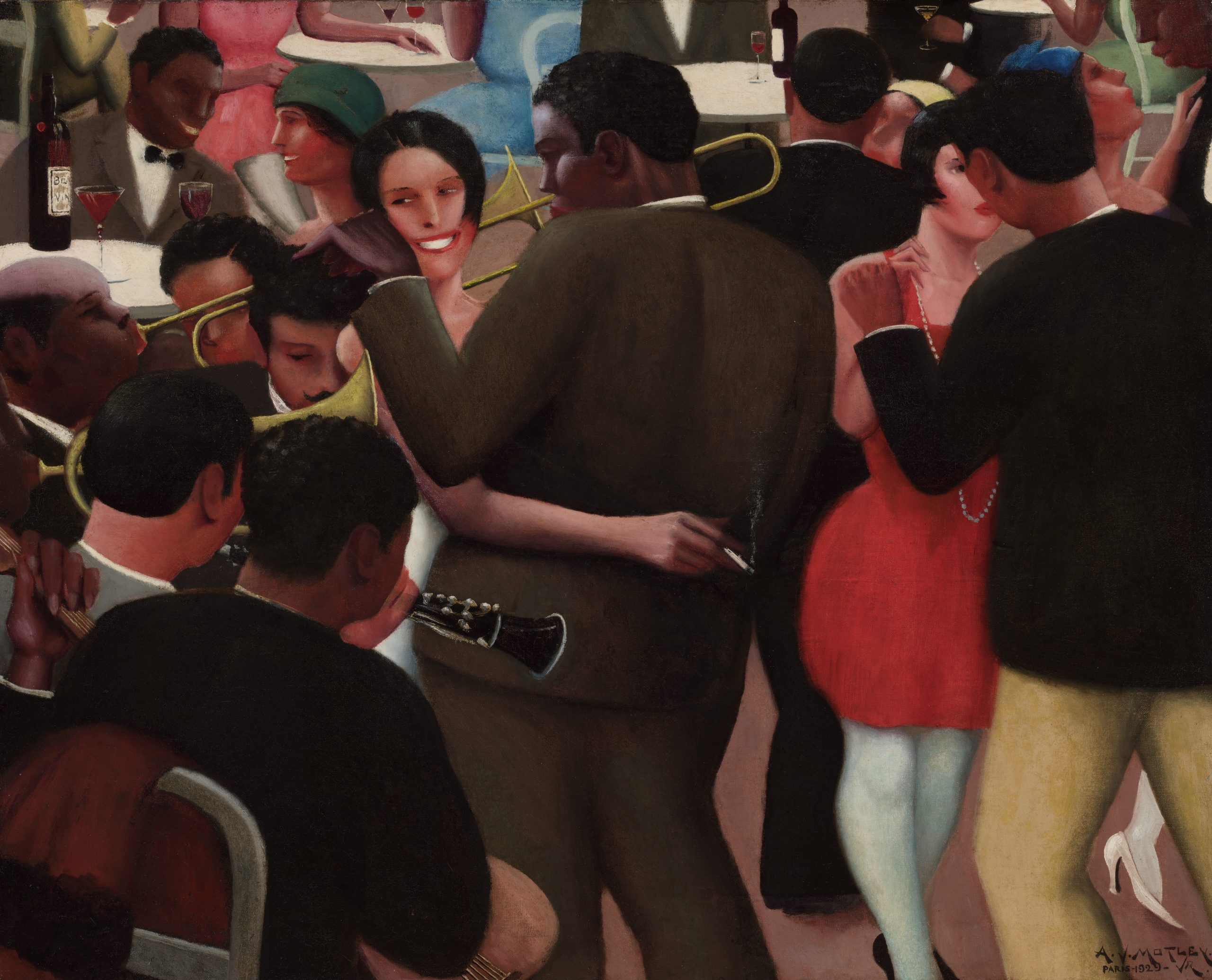

These two artworks in their connotative roles might help us understand the multiplicity of modernist cultural aesthetics at work in structuring the exhibition. While Johnson’s Woman in Blue was used to promote the exhibition on banners, MTA marquees all over the city, and the MET’s website, the face of Waring’s girl sat peacefully shining in multiples just at the entry to the galleries, displayed in a pyramid shape. To my mind, Waring’s depictions of girls across the exhibition represent the internal-looking gaze of the institution. It is a gaze similar to my mother’s, which reflected her dreams of raising me to become a European-style cosmopolitan, gleaned from her own understanding of ways of life closer to that of Black Caribbeans expatriating to France earlier in the twentieth century. See, for example, Archibald J. Motley’s 1929 painting Blues, depicting Black Caribbean expats at a café in Paris, a city that would later welcome Josephine Baker and James Baldwin.

Dr. Denise Murrell, the curator of The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism, explains that this exhibition is the first to center African American contributions to the development of international art movements writ large. As slavery was slowly abolished across the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries by France, Britain, and finally the United States, millions of African-descended peoples crisscrossed the Americas and Europe to destinations of their own choosing to pursue livelihoods that created the cosmopolitan culture of modern life. The play between the styles of the two painters deployed to advertise the exhibition denotes the three fundamental criteria underlying how the exhibition operates vis-a-vis qualification for, convention within, and correction to the canon of modern art. In part, the “Renaissance” or idea of re-birthing the Negro after slavery in the United States was a modernist project, and the Harlem Renaissance (centered between 1920–1940) is one period in which Negroes theorized themselves in a way that would once and for all beget the flourishing of Black people everywhere.

By scaffolding the exhibition according to the intellectual history of its leaders, Murrell broadens the historical grounding of the New Negro Movement. The New Negro was theorized to organize the ideals of a collective self-respect, including but not limited to rebuking all policing by white society in its horrific attempt to maintain the protocols of the plantation. The founding philosopher of the New Negro Movement, Dr. Alain Locke, inherited, imbibed, imbued, rescinded, and rejected an expansive philosophical terrain in order to lead, and organized a Black-led Reconstruction during the early waves of the Great Migration. Locke, author of The New Negro, a multi-disciplinary anthology of Black cultural forms, and William Edward Burghardt (W.E.B.) Du Bois, an activist and founding researcher in the emerging discipline of sociology, debated the diverse aesthetics of the movement, reflecting an idea of the Negro who happened to have become planetary by virtue of the labor that created the modern world.

In the lecture-essay “Criteria for Negro Art” (1926), a perennial favorite if not also a manifesto of the New Negro art, Du Bois writes:

Thus all Art is propaganda and ever must be, despite the wailing of the purists. I stand in utter shamelessness and say that whatever art I have for writing has been used always for propaganda for gaining the right of black folk to love and enjoy. I do not care a damn for any art that is not used for propaganda. But I do care when propaganda is confined to one side while the other is stripped and silent.1

Du Bois’s essay raises the question: what could it mean to change this world such that respect for humanity could be recognized by way of Black people simply being themselves, without the burdens of appearing under the conditions of a white gaze all too eager to misconstrue our being?

⁂

The exhibition begins in a gallery titled “The Thinkers.” Portraits of Alain Locke, W.E.B. Du Bois, two of the New Negro Movement’s great theorists, are hung with a vitrine in which a poem by Langston Hughes on lynching is paired with an illustration by Jacob Lawrence. The illustration, titled One Way Ticket, shows the practical action of families moving out of the South to escape escalating and legally sanctioned white terrorism, which had been unleashed to control and subordinate the newly freed men, women, and children. Hughes writes:

Who Lynch and run,

Who are scared of me

And me of them.

I pick up my life

And take it away

On a one-way ticket—

Gone up North, Gone out West,

Gone!2

In the context of literal escape from lynching mobs, the New Negro took up agency where he could and moved away from the predatory situation of the post-Civil War “New South.” By arguing for the beauty and pride of Black people, the idea of the New Negro not only acted as a form of psychological self-defense, but also offered a cultural vision of the past, present, and future, born out of necessity to counter the rage now engulfing the defeated whites of the secession states. For hundreds of years, planter-class whites wrongly imagined themselves as genteel; they had convinced themselves they were doing the Lord’s work to “care for” the Negro.

“By arguing for the beauty and pride of Black people, the idea of the New Negro not only acted as a form of psychological self-defense, but also offered a cultural vision of the past, present, and future, born out of necessity to counter the rage now engulfing the defeated whites of the secession states.”

The formal organization of and visibility of the Ku Klux Klan became the most prominent example of the white planter-class and their descendants’ (ongoing) attempt to maintain the old order in the “New South.” In Aspects of Negro Life: From Slavery to Reconstruction (1934) (on loan from the New York Public Library’s Schomburg Center for Research on Black Culture), the panoramic history painter Aaron Douglas depicts a monumental re-telling of where we have been and where we are going, offering a factual American genealogy that counters white fantasies of civility.

The painting returns us to the immediate aftermath of the U.S. Civil War (1861–1865). As triumphant Union soldiers depart the South back to the North, Douglas centers a Black leader, surrounded by celebrants, who points the way out beyond the cotton fields. Yet we also see the Klan. One member brandishes a Billy club or a sword held up high—in a resentful mob just like the Klan members marching on the capitol in Nashville, Tennessee today. To depict Negroes as even having a history is already to philosophically reposition our people as having a self-consciousness, not only partaking in judging the world, but also capable of self-assessment and autonomous self-direction. To be shown, as Douglas masterfully does, as free to create a new way of life is to announce a countervailing truth and rebuke the lies taught, learned, and repeated in order to justify slavery. This is the moment which marks the United States’s entrée into modernity.

⁂

Yet the boundaries of the exhibition stretch far beyond the borders of the American North and South. Du Bois and Locke understood that the Negro was always already cosmopolitan, or at least should be understood as international (of the Americas, Europe, and Africa) by way of the very conditions of this aggrieved and hopeful population’s unholy formation. It is simply inaccurate to center Paris as a “finishing school” for Black people, as a place where African-Americans expatriated to during the 1910s and 1920s in order to simply familiarize themselves with the advances of European modernity. As Dr. Lewis Gordon reminds us, “people in Paris [were also] studying the intellectual and artistic production of African-Americans, it’s a two-way flow.”3

In Du Bois’s reconfiguration of nineteenth-century Romantic-era theories of race, all of the artistic contributions of “the Negro race” worked as a whole, complete unto itself, albeit with many parts. This is why in the United States artists hailing from Midwest and West coast cities, like Chicago and Oakland, could be as much at home taking up aesthetics familiar to Ethiopia and Egypt as they were influenced by Southern kin. The photographer James Van Der Zee, who would “bling out” his work by drawing on his negatives to add rays of light to his prints, captured something of this mystical feeling of pride that many Black people continue to feel and share with one another around the world, even when meeting for the first time. In The Barefoot Prophet (1928), a rare self-portrait, the artist sits barefoot in a high-backed, finely carved wooden chair in rapt contemplation. On his desk sits a candelabra illuminating a study. With a cane in one hand, we can imagine the artist preparing to take a stroll in between reading the book at his elbow—an activity punishable by maiming only a generation earlier. In the rapid changes to ways of life captured by the shift from agrarian to industrial economies, this portrait of Van Der Zee in his study works to individualize and complicate the image of the many ways Black people brought about modernity.

In Blues Legacies and Black Feminism,4 Angela Davis posits that the Blues is an emotionally poignant genre directly arising from the separation between Black couples in the aftermath of slavery. Black men, in particular, were the first to move—often leaving the South ahead of their families in pursuit of employment. Between the federal government’s low-wage Reconstruction-era sharecropping scheme (which meant many families never left the plantations from which they had just been emancipated) and hiring discrimination which worked hand-in-hand with new vagrancy laws and legally sanctioned lynch mobs in “sundown towns,” the necessity of migration after slavery wrenched families apart over and over again. Davis posits that the conditions of precarious labor following the legal abolition of slavery profoundly shaped the aesthetic formations of African Americans.

This is also the reason why sociological studies carried out by Davis’s predecessor Du Bois and presented in his touring Exhibit of American Negroes on display at the 1900 Paris International (see the recent exhibition Deconstructing Power: W. E. B. Du Bois at the 1900 World’s Fair at the Cooper Design Museum in NY, December 9, 2022-May 29, 2023) remains so important to recognizing how modernity was made. There is no civilizing mission that could compare with the innovations brought about in the struggle to overcome the fantasies of Euro-supremacy. However, while the New Negro movement upheld the democratic ideal of affirming the dignity of Black people across classes and continents, it also relied on the leadership of Harlem’s philanthropists and the socialites who organized the first exhibitions of Negro art. Du Bois recognized this special leadership class in the phrase the “Talented Tenth,” espousing the call to develop the capabilities of the best among us. He saw each of us living authentically in our respective roles across our complicated and uneven modernity, working together to uplift the race.

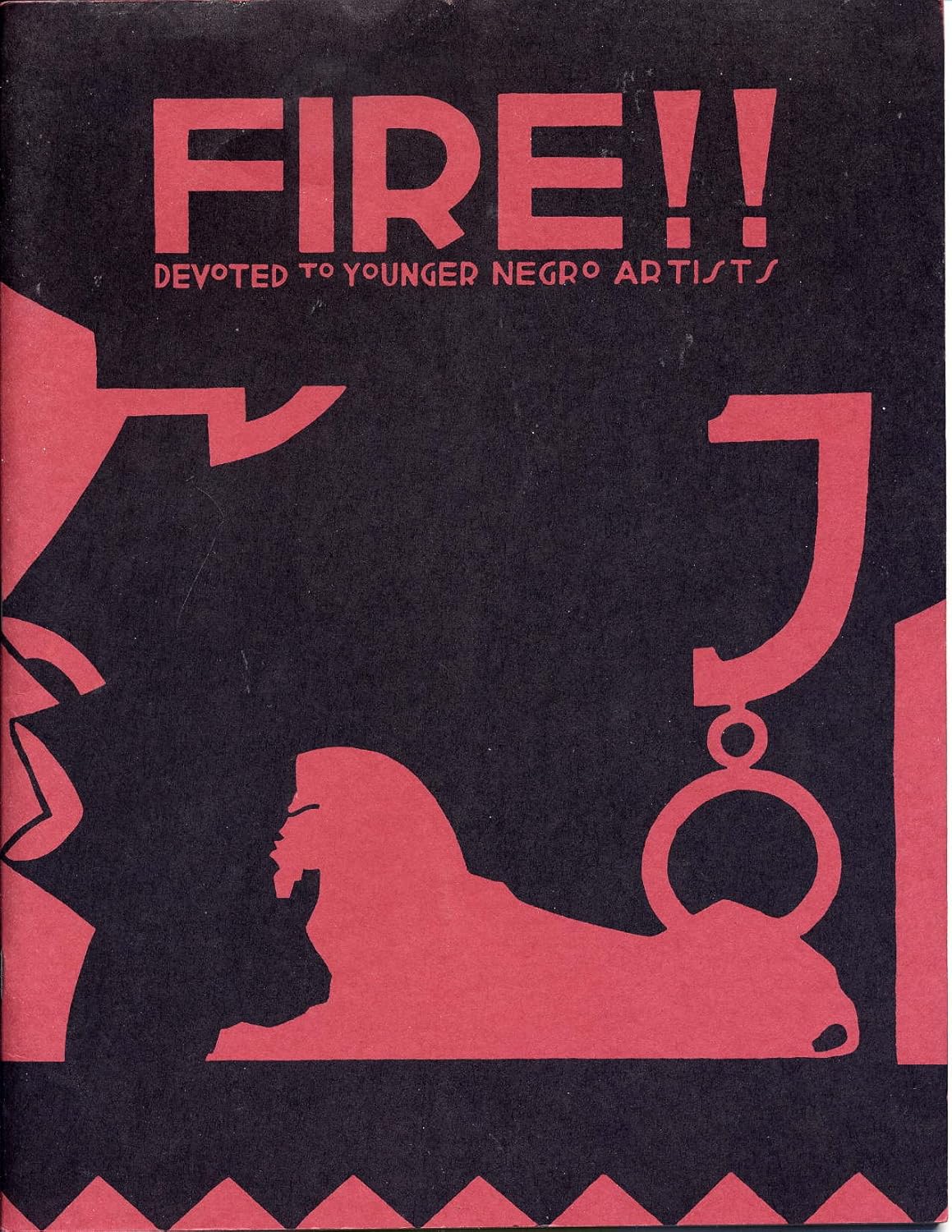

And yet, Du Bois’s “Talented Tenth” does not describe every member of the community who worked under the banner of the New Negro movement. For example, Zora Neale Hurston dramatized the story of heartbreak of a Black woman who knows she cannot compete with her man’s light-skinned lover in the play Color Struck (1926), first published in the African-American literary magazine Fire!!. Although the play was published in print, no theater, in Harlem or otherwise, would produce the play set in Jane Crow Florida.

It is only recently that I have come to realize that the internalized standards of beauty that my mother imparted to me reflected her fear for my perceived attractiveness as a woman in this world. When I look at Meta Warrick Fuller’s In Memory of Mary Turner as a Silent Protest Against Mob Violence (1919), which honors the life of a Black pregnant woman who was lynched, I think of the artist Mary Elizabeth Enoch Baxter’s Consecration to Mary (2021), a multipart photographic work that connects the ongoing histories of abuse faced by Black children to “adultification bias,” and specifically the abuse of Black girls by the white American artist Thomas Eakins. Now, I deeply appreciate my own mother’s fears for how I might survive in this country when I consider the grief felt by the children Black mother like Sonya Massey, who was murdered by the police, or that of Tamika Price, the mother of Breonna Taylor. In her own way, my mother merely expressed her concern over my capacity to find some relative security in the peace of a family she had wanted for both of us all along.

Bessie Smith’s era, as described by Davis, reminds me of something that photographer Ming Smith said in an artist talk I attended last year: although many assume otherwise, Blues has been the core inspiration for her lens practice, not Jazz. Through Blues, the American nation-state’s uncontested contribution to modernity and a genre perhaps only possible by way of uplifting the range of emotion felt by working Black women, Bessie Smith has inspired artists across all genres of American music and beyond. I feel her poetry in a recent work by tarah douglas, untitled (come meridian and meridian come) (2024). The installation obscures the juiciness of a pomegranate hidden in plain sight behind a deep rouge velvet curtain, which is only opened at times desired by the artist. I am so proud to be Black from multiple sites, to have grown up in the United States by way of immigrants like my mother who blessed me with so many ways of being Black. From her and her and her, I take pleasure in being my own kind of Blue-black woman, as unfazed as a girl happy with her pomegranate.

Darla Migan, Ph.D., is a philosopher, critic, and curator. She has published reviews on solo exhibitions by Faith Ringgold, Abigail DeVille, Tau Lewis, Julie Mehretu, Wangechi Mutu, Akeem Smith, and Stacy Lynn Waddell. Since completing her dissertation on the Harlemite Dr. Adrian Margaret Smith Piper, her research has expanded to include the shifting conditions of global art markets. She is an alumnus of the Independent Study Program at the Whitney Museum of American Art, a recipient of an Andy Warhol Arts Writers Grant, and a recipient of the Rabkin Prize in arts journalism. Dr. Migan curates the experimental art gallery Variable Terms and teaches the open online course Philosophy for Artists.

NOTES

1. W.E.B. Du Bois, “Criteria for Negro Art,” The Crisis, no. 32 (October 1926): 290-297.

2. Langston Hughes, One Way Ticket, with illustrations by Jacob Lawrence (New York: Alfred Knopf, 1949), 62.

3. Black Abstraction | Black Existentialism Roundtable held at the Institute for Fine Arts April 16, 2024 in conjunction with the exhibition Americans in Paris: Artists Working in Postwar France,1946–1962 at Grey Gallery (March 2, 2024–July 20, 2024).

4. Angela Y. Davis, Blues Legacies and Black Feminism: Gertrude “Ma” Rainey, Bessie Smith, and Billie Holiday (New York: Pantheon Books, 1998).