Michele Abeles’s Turbocharged Economy of Mimicry

Michele Abeles’s critically acclaimed exhibition October featured photographs of manufactured death and mayhem. Images of robotic apparitions donning peasant-core looks cool enough to pass for Vaquera models, tombstones, and other dollar store object d’art hung in the Chinatown-based gallery 47 Canal from August to September of 2020. Of course, when the artist shot this series during the previous autumn, she couldn’t have known that her upcoming exhibition of front-yard satirical theater would coincide with a once-in-a-hundred-year plague. Bad timing, right? A circumstance of Monty Python-level gallows humor. Or maybe a way to lighten the mood. Macabre humor is, after all, often the only touchstone that remains after a tragedy of that scale. (Can you name any songs from 1665 that aren’t “Ring Around the Rosey”?)

Turbo is Abeles’s inaugural post-Covid effort in our currently post-photography world (contemporary photography being just another victim of the pandemic). In this mega-viral era, characterized by remote interactions and heightened isolation, not every artist has the bandwidth to keep the concept of bemused and benevolent inquisition at the forefront of their practice.

But Abeles’s Turbo delves into this space without trepidation. In 2024, the practice of working exclusively in the medium of photography feels especially timely. Millions in advertising dollars have been spent by corporate behemoths to convince us that we are “all photographers now,” and have been for over a decade. Maybe it’s somewhat like the old adage of the philistine who gazes upon a masterwork of abstraction, unmoved, and whose only reaction is to grumble, “my child could do that.” What Abeles makes very clear with Turbo is that, even if we are “all photographers now,” and have been for a decade: No, you can’t do that. But she can, and does.

Abeles’s vision in Turbo offers a reinterpretation of delicious wholesomeness, incredibly welcome in our current moment. The title itself seems to recall a painfully saccharine animated Disney character’s name while simultaneously offering a subversive dig at outdated accelerationist movements. This exhibition gives priority to tenderness, care, and fortitude as opposed to the latter’s self-actualizing focus on blight, dilapidation, and scorched earth human carelessness. Abeles’s investment in tenderness has a sophisticatedly comfortable, anarchistic quality that penetrates the complete set of prints, and swiftly avoids nostalgia.

“Abeles’s investment in tenderness has a sophisticatedly comfortable, anarchistic quality that penetrates the complete set of prints, and swiftly avoids nostalgia.”

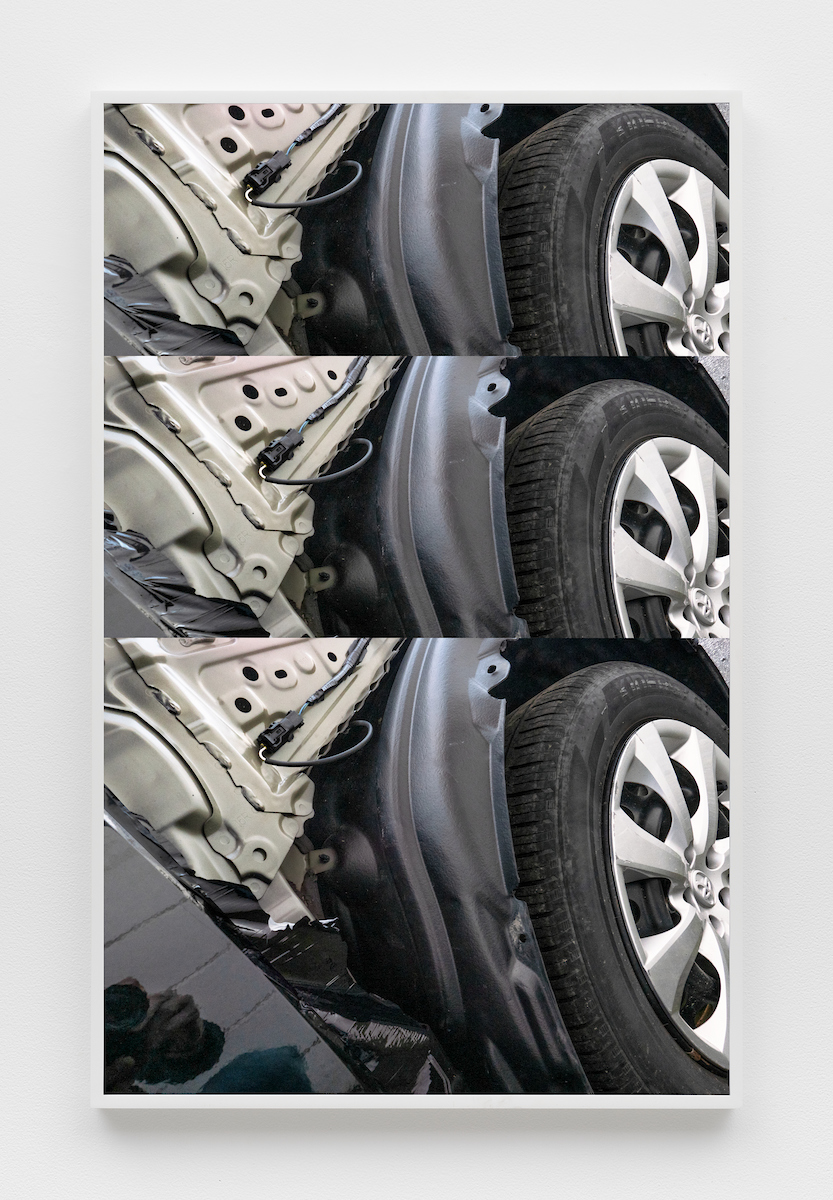

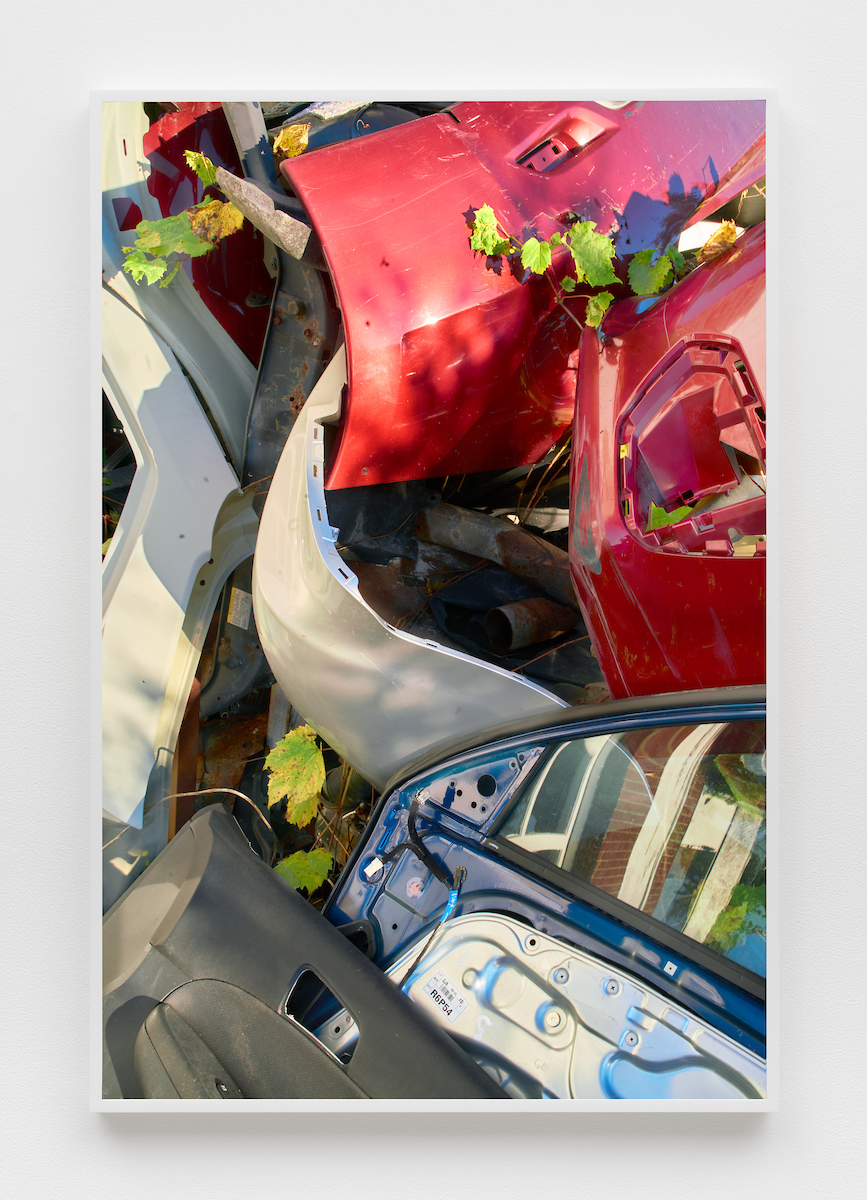

The majority of the show consists of beautifully printed disembodied car parts, most of which are affixed with modified chrome frames. As with the images in October, these images are haunted—but in this instance by actual, not manufactured, decay. These works dialogue with the bygone optimism of American car culture preluding its environmental reckoning—harkening back to the decades before we truly understood the environmental impact of the automobile industry, especially on future generations. Pieces like 300 Billion Words feature a once brilliantly painted crushed Sedan left in a pile, half-gone to its great reward. The prominent choice of cherry red in Abeles’s prints is no “accident” a but deliberate invocation of deeply entrenched cultural rhetoric.

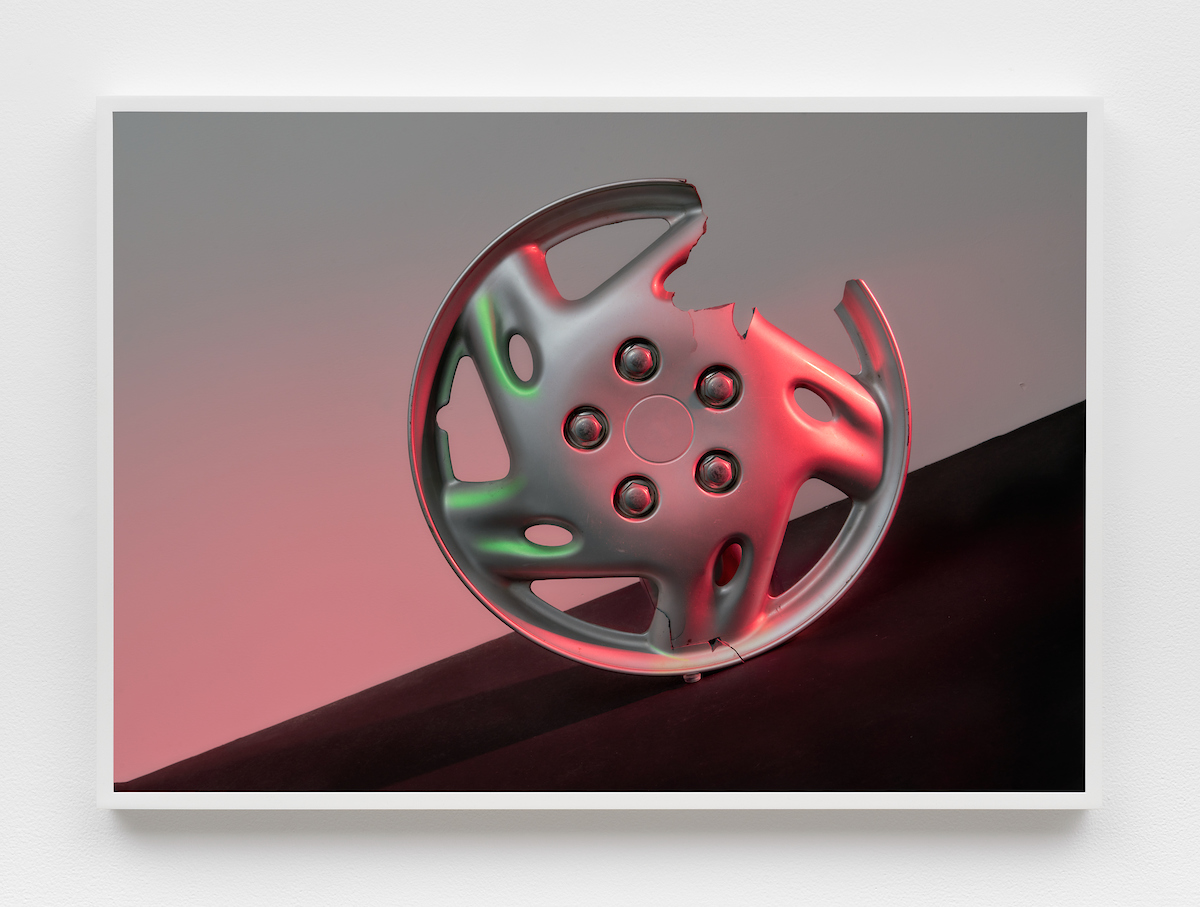

One of the most potent representations of cherry red’s cultural cachet in American car and youth culture can be found in the music video for Van Halen’s 1984 song “Panama,” a sex-positive anthem in which the lyrics declare cars and bodies as synonymous. Abeles’s strangely anatomized auto abstractions can be connected to endless varieties of entertainment, yet are completely devoid of human touch. Days of Thunder offers us a gray souped-up hubcap from an economy car—a clever riff on the ubiquitous commercial glamor shot. Another object of desire on its own. One could argue that this piece is reinterpreted flatly, for a materials-obsessed artist like Abeles who appears in no way to be grieving the loss of these beauties and the middle-class suburbia in which they once roamed.

In Turbo, automotive images are sharply contrasted with another smaller but potentially more aerodynamic roomie in the gallery: Bill, Abby, and Ruby parrots. While birds have often been a dynamic subject in photography (just think of Heji Shin’s Cocks series), these rescued avians are the undeniable headliners of the exhibition. Abeles’s portrayal of these birds is marked by a sharp presentation imbued with spirited closeness. Take, for example, Bill (2024). The bird gives a standoffish, Tony Sopranoesque puffed chest, full of attitude, while looking the viewer directly in the eye. I almost wondered, “Do I owe this bird money?” Never mind their dangling gold chain—only some call it a “parrot bell.” The parrot’s handlers recently discovered that Bill is actually a girl, but the name still seems appropriate. Conversely, Ruby (2024) leans in clear-eyed with bright red quaff, full of curiosity, undaunted even as Abeles’s lens creeps incredibly close. Interestingly, there isn’t a word in the English language to describe an animal’s own “humanity.”

During her research for the exhibition, Abeles became interested in the concept of “parroting,” a psychological term which mostly applies to social media behavior, defined by Google’s Gemini as “the blind reposting or sharing of content without critical analysis or value addition.” And, at its core, the act of producing a photograph is indeed a form of mimicry, which the artist acknowledges. The capturing of images from the empirical world, interpreting them, and presenting them back to that world to get a reaction or even a reward is a process strikingly akin to the parrot’s mimicry. Especially since we have such little understanding of the world we are mimicking our way through at any given moment.

Turbo reinterprets commercial fields of understanding, as well as our connection to the natural world and our delusions of grandeur, socially, historically, and personally. No tricks here, only treats.

Lyndsy Welgos is a New York-based artist and the founder and Executive Director of Topical Cream. Welgos is known for her portraits of female-identifying artists, which have been published widely, including in The New York Times, Vanity Fair, Vogue, The New Yorker, among many others.