Liberation for Likes

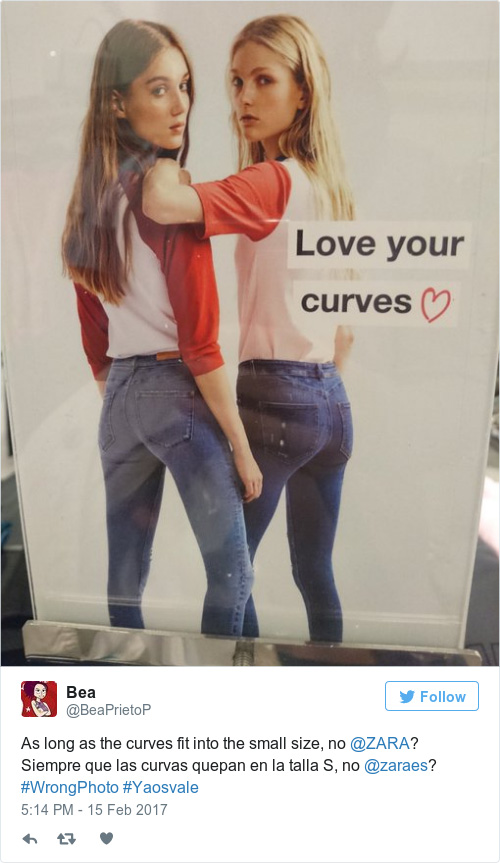

Two thin, white models glance over their shoulders, arms poised to frame their perfectly photoshopped asses. “Love your curves” the ad, one of Zara’s latest for their line of “Body Curve Jeans,” reads. The campaign is in itself an oxymoron, but that’s hardly shocking to anyone familiar with marketing tactics and the fashion industry’s tendency to warp body ideals at the expense of the average woman. Also not shocking was the internet’s reaction: widespread outrage and the denouncement of the fast fashion chain’s problematic casting.

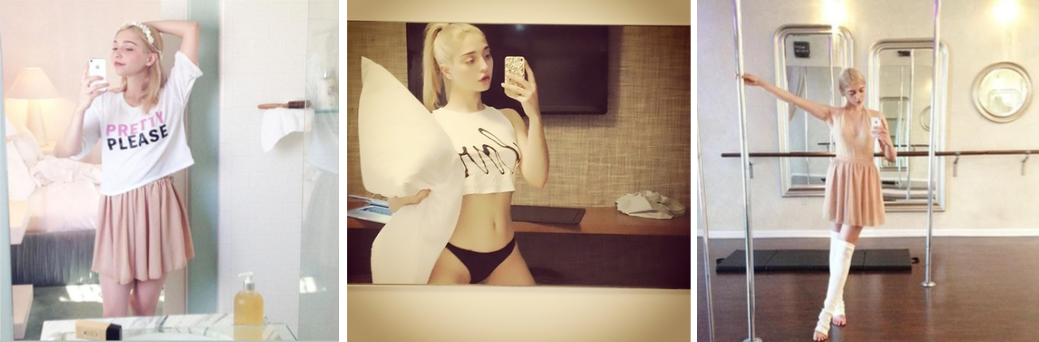

Selfies from feminist artists and activists have similarly been critiqued for their inaccurate representation of the feminine body. Once an idealized form of self-empowerment and liberation, feminist selfies have become the highly contested topic of countless new media panels and essays, resulting in repetitive, myopic discussions surrounding teen girl photography and the failures of modern feminism. Critiques of the highly visible arbiters of so-called selfie aesthetics, namely young, white, femme activists, help to identify the specific images of feminist culture that are being co-opted into the mainstream. What they are lacking, however, is that the very networks that host this content make the corporatization and deradicalization of feminist ideologies possible.

It’s easy to blame arbiters of the “female gaze” for the corporatization of the selfie politic, and even feminism as a whole. The rising popularity of teen girl photographers and their easily replicable artistry characterized by dreamy, bubblegum backdrops and colorful light filters has resulted in the homogenization of feminist imagery online. These works, popularized by selfie aesthetics and the youth culture publications that promote them, increase the visibility of “desirable” bodies and reinforce what writer and artist Aria Dean refers to in “Closing the Loop” as “the functional specificity of ‘Feminism’…exclusionary to non-white women—as well as trans, nonbinary, and disabled people.”

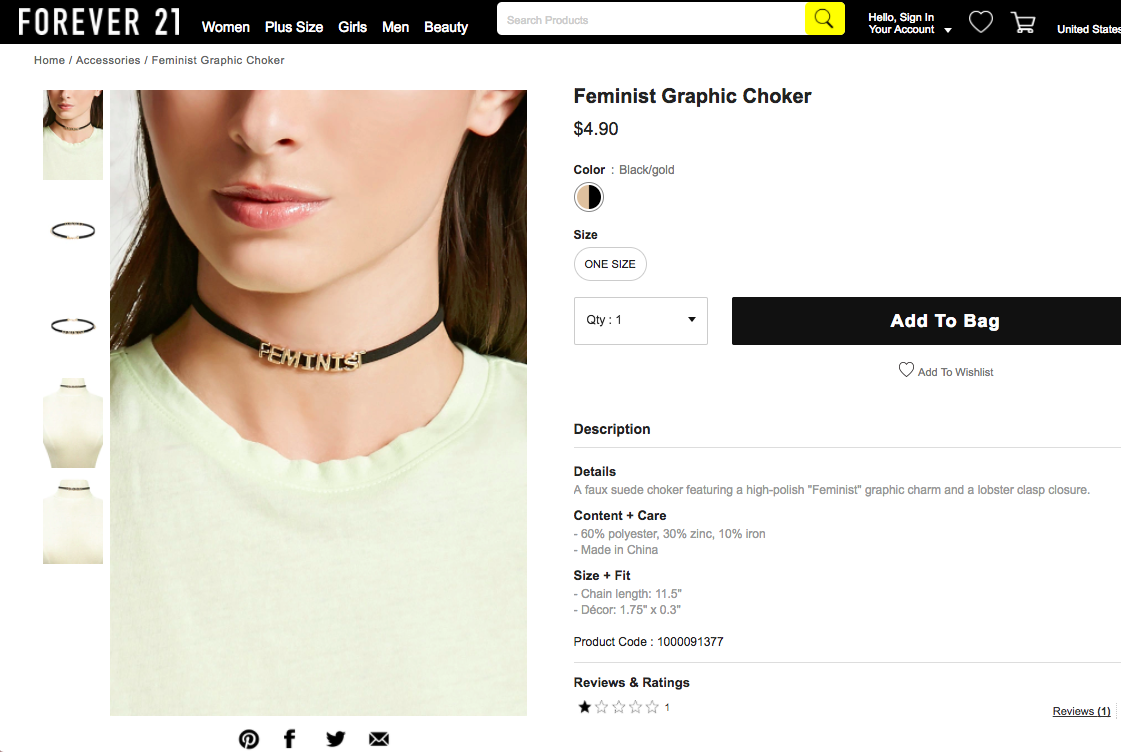

On Instagram, the proliferation of #empowerment via popularized accounts featuring emoji-covered nipples and anti-censorship commentary has contributed to the trickle-up of “selfie aesthetics” into the corporate mindset. Easily replicable, accessible imagery gains traction while hashtags and data-mining encourage tastemakers like Pantone to adopt gender-neutral aesthetics. Corporations use words like “equality” to cater to Generation Z, transforming pink and blue mood boards into “feminist” ideologies that can be purchased at Forever 21.

The rise of this consumer-oriented feminism is the result of what Jessa Crispin, author of the controversial manifesto I am Not a Feminist, sees as a rebranding of radical ideology into a universal form of identification for “all women.” Crispin cites celebrity endorsement of feminist identity and the resulting pacification of feminist ideology as contributing factors for the expansion of the movement into a generic form of white, privileged, feminism—or what might be referred to as “Pussy Hat Politics.”

But how did we get here?

In her 2013 lecture “The Limits of the Web in an Age of Communicative Capitalism,” author and academic Jodi Dean states that the structure of networked platforms like Facebook and Instagram has contributed to cyclical conversations that dominate online political discourse and activism. She argues that technology fetishism encourages active participation in social media—the completion of unpaid “visual labour”—that solidifies neoliberalism via the circulation of inexorable images that hold little meaning or value. Content is shared across social media platforms in an attempt to facilitate political activism but instead creates a capitalist sounding board that encourages repetition rather than meaningful responses between users.

The failure of networked activism to promote nuanced debate has resulted in the creation of ephemeral, pseudo-political communities online—particularly when it comes to feminism. Like-minded women foster #freethenipple discourse in an attempt to subvert the male gaze, but so-called feminist selfies become little more than myopic representations of current beauty standards: repetitive images that reinforce hegemonic narratives of beauty.

What’s more, the “attention economy” ensures that online art, and in particular, selfie feminism, is created in accordance with what is seen as desirable within the network. Teenage girls subconsciously take selfies in the style of their internet-famous peers in an attempt to earn likes while artists self-objectify to reverse the male gaze. Networks shrink according to algorithmic structures, reflecting both individuals’ consumptive needs and “woke” aesthetics—generating more likes and thus collecting more data. User preferences are then mined, extracted, and sold to corporations that inevitably profit off targeted advertising purchased from these very networks.

Users look inward, neglecting their role in the creation of these online echo chambers, and thus failing to realize their own exploitation at the hands of corporate networks. “Ordinary people ‘share’ while elite network presences generate unprecedented fortunes,” says futurist Jaron Lanier in Who Owns the Future?. “Trinkets tossed into the crowd spread illusions and false hopes that the emerging information economy is benefiting the majority of those who provide the information that drives it.”

What’s more, utopian narratives that identify social networks as democratizing forces—for example, the notion that Instagram increases the visibility of bodies that are usually marginalized by mainstream media—though not entirely false, have ignored the reality that these networks promote accessible content, and use the labor of average users to do so. Algorithms boost the ranking of already-popular accounts, increasing the number of followers awarded to well-known users who are then able to monetize their online fame. This means, for example, that insta-famous photographers like Petra Collins and Mayan Toledano are able to win big money campaigns with companies like Urban Outfitters, Gucci, and Adidas, while their followers are left posting bedroom selfies to an unresponsive crowd.

For the average user then, rewards come in the form of a few likes, followers, or the increasingly evasive notion of self-empowerment (a reward that might be more of an expectation than a reality). These small wins encourage users to continue engaging with the platform, while the promise of online popularity keeps them hooked. Privacy policies, along with the tendency of left-leaning users to police each other’s content for PC-related fouls, ensure that users self-censor online, further diminishing community diversity and thus limiting the possibility of uninhibited activism.

In their book Inventing the Future: Postcapitalism and a World Without Work, Nick Srnicek and Alex Williams argue that because social media is “premised on the maintenance of an online identity, ‘politics’ tend towards the self-presentation of moral purity.” Users are ultimately concerned with self-representation and because of this, fail to create the conditions for “real” political change. As a result, “politics comes to be about feelings of empowerment masking an absence of strategic gains.”

The gains that are made as a result of networked activism are often misperceived as a win for online communities when they only benefit a select few. Adidas putting women of color and girls without makeup in advertisements is hardly revolutionary. What’s more, the adoption of Dove-esque marketing tactics and the employment of terms like empowerment and real beauty™ are little more than a ploy for profits in the name of “collective womanhood,” a reflection of the corporate inclination to promote fantasies of community and acceptance as a means of co-opting liberal consumer ideology.

“Once assimilation becomes a possibility,” says Crispin in an interview with Jezebel, “You kind of abandon your principles because it’s much easier to just enter the system than destroy it.” For activists, good intentions might supplant feelings of guilt, but our participation in exploitative economies means that we are complicit—even if we don’t have thousands of followers.

Taylore Scarabelli is a New York-based writer and photographer whose work focuses on fashion, feminism, and technology. She has written for Bullett, Dazed, Flaunt, Nylon, Under the Influence, and You Do You, amongst others.