Lena Henke: Heartbreak Highway

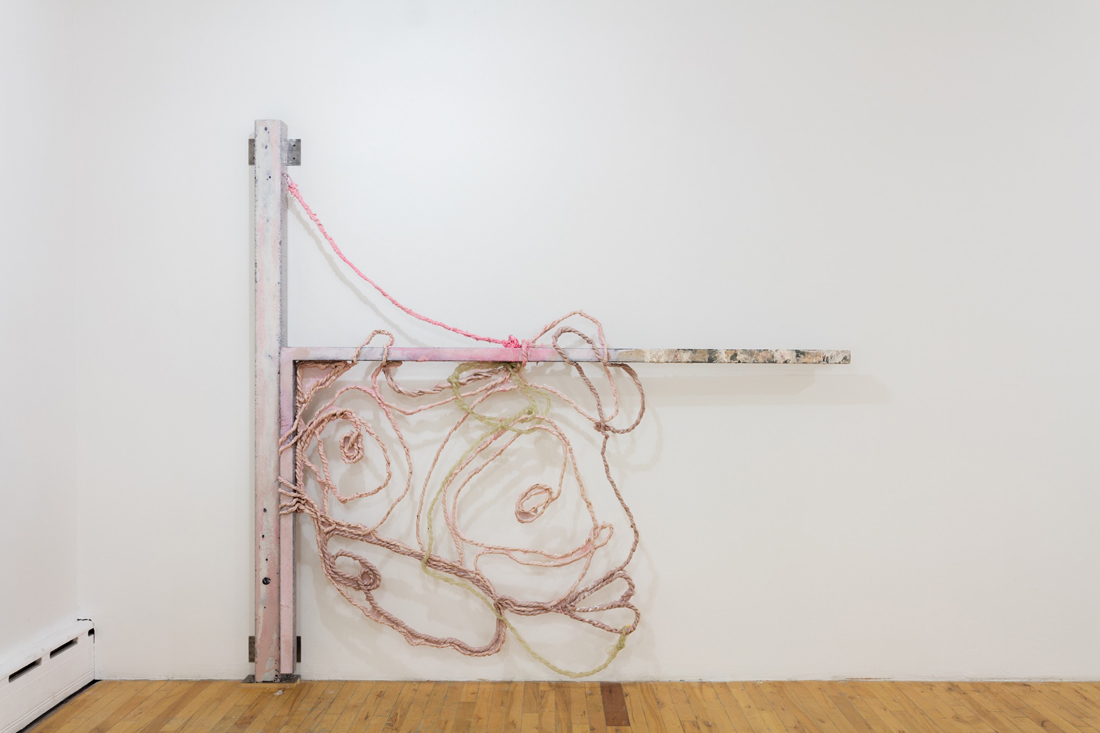

Lena Henke placed an ornate, bright red gate at the threshold to Heartbreak Highway at Real Fine Arts. Decorative tendrils suggesting ropes or braids, which seemed to loosely outline a feminine hairstyle, hung from a central bar that was blocking the gallery doorway when I arrived at the space, though the gate easily swung open when pushed. This work, Gridlock Sam and his partner (2016), was named for the New York cab driver turned transport engineer Sam Schwartz, who popularized the term “gridlock,” and introduces an exhibition that summons messy flows and movements—a kind of unlocking of grids.

Heartbreak Highway features porcelain sculptures of horses’ feet, glazed in creamy architectural speckles suggesting brickwork, contrasting with shiny smacks of dark lacquer around the hoof. As the shoe curves up and becomes a horse’s foot or leg, the forms become over-voluptuous and feminine, robust yet awkward. Two more movable gates are placed at the rear of the gallery, these ones ballet-ribbon shades of pink and peach, which outline the shape of a horse’s face and a girl’s face. Two of the horseshoe sculptures point slightly inward to face one another like a pair of large clumpy patent school shoes worn by a hesitant child.

The hollow forms of the hoof sculptures suggest buildings, however, several plastic milk containers create a kind of hybrid model home, made of junk and animal bodies. Messy, feminized forms, they suggest families—mothers and daughters in particular. The semi-opaque plastic of the milk bottle can be seen to describe a rudimentary model shelter or a doll’s house, while the milk is suggestive of mothering (as well as being the classic example of abjection as described in Julia Kristeva’s writing: “‘I feel like vomiting the mother,’ she writes as her lips touch the skin on some milk.”1) Several sculptures have vagina forms in them, crevices or cleavages with coins pushed into them as though into a slot in a laundrette. Burgeoning female sexuality, the girlish passion that young girls can have for horses, psychoanalysis, the gendered labor of cleaning and mothering—such themes are present in Henke’s exhibition as dredged issues, which have returned to us from the twentieth century like trash from a riverbed that has remade itself.

In New York, trash does return in such a way. Down at Dead Horse Bay in Brooklyn workers used to grind and melt down horse bones into glue, but today mid-century garbage regularly washes onto the shore, leaking from below the water’s surface. In 1926, the infamous city planner Robert Moses joined Barren Island in the bay to the rest of the Brooklyn landmass using sand and landfill waste. The connecting landmass is now leaking and seeps old waste into the surrounding water. The sound of chiming glass can be heard when waves hit the shore. Henke’s sculptures are amalgam, mutant forms that suggest a reconstituted world, a trash world, a ghost world, a female world that oozes beneath New York like a subconscience.

A brutal line from Moses himself was used as a kind of epigraph to Heartbreak Highway in the press release; he describes developing in an overbuilt metropolis as akin to hacking with a “meat ax.” In light of his words, it’s possible to see the horse feet in the exhibition as violently dismembered. Indeed, the figure of Moses appears as a kind of bête noir in the exhibition. As well as touching associatively on his sloppy work at Dead Horse Bay, Heartbreak Highway stages a face-off with one of Moses’s most notorious works of butchery, the Brooklyn-Queens-Expressway (BQE), which tore through the surrounding neighborhood and today casts a towering shadow over Real Fine Arts’s space. Against the curlicues and contours of Henke’s works, Moses’s approach expresses extreme-edge rationality—a form of power that bulldozes through the world in straight lines—yet Henke extracts elements of wild surrealism at the center of this masculine vision, the leak that persists.

In Umberto Eco’s theory of the ”Open Work,” he describes artwork that speaks in a language of confusion, instability, and reconstituted parts as a form of social commitment or protest. The artist implicates herself by transforming the formal language into something unstable so as not to carry the sense of an orderly, coherent universe which cannot speak to a world in full crisis. “The moment an artist realizes that the system of communication at her disposal is extraneous to the historical situation she wants to depict, she must also understand that the only way she will be able to solve her problem is through the invention of new formal structures that will embody that situation and become its model.”2 Henke blocked out the windows of the gallery so that the BQE could not be seen, and in its place installed alcoves with small Lazy Susans, on which her ceramics were displayed. The spinning discs had four names each, which changed at different angles of rotation—Eugene, Barb, Joe, Ada, and so on—suggesting a neighborhood family around a dinner table in the early part of the twentieth century. This unstable work has no fixed position because certain ghosts do not rest, they transmogrify.

Henke’s models are irrational, animal, and sexualized, but is there anything rational about the BQE or the glass and steel towers erected all over the city in their hard phallic lines? The grid maintains its power overground, while beneath, the city’s subconscious expels new forms.

Laura McLean-Ferris is a writer and curator based in New York. She is adjunct curator at Swiss Institute and regularly writes essays, criticism, and interviews for Artforum, ArtReview, Art-Agenda, frieze, Mousse, Rhizome, and Flash Art International.

NOTES

1. Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror (Columbia University Press, New York, 1982), 56.

2. Umberto Eco, “Form as Social Commitment” in The Open Work, trans. Anna Cancogni (Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1989), 157.