Lena Henke at Kunsthalle Zürich

Yes, I’m pregnant! This was my first introduction to German-born, New York-based artist Lena Henke’s work. The exhibition took place in 2014 at Skulpturenmuseum Glaskasten Marl (which translates to “sculpture museum, glass box of the city of Marl”). Back then, I found it odd that an up-and-coming contemporary artist-friend seemed to comply rather easily with the traditionalist mono-media politics of a museum. However, I was taken by the title, the ballsiness, the confusion. And I have learned a lot from Henke’s use of titles ever since: they are the nuanced narrative counterpart to her work’s technical daring.

Take, for instance, An Idea of Late German Sculpture; To the People of New York, Henke’s solo exhibition at Kunsthalle Zurich this spring 2018. Here too, the exhibition title performs a tongue-in-cheek vorauseilenden gehorsam, a sort of anticipatory obedience to a set of expectations swelling forth from the patriarchal association of sculpture—particularly in conjunction with Germanic tradition and the notion of a late, matured body … of work.

Big names ring a bell; big balls welcome you at the door. The show starts with two massive twin sculptures coated in bright green rubber titled Ayşe Erkmen’s Endless Knee—Erkmen being a Berlin-based Turkish artist, sculpture teacher, and exception in her male-dominated field. One of the irregular spheres sits on the floor, the other atop a shelf. While this mode of display suggests the fate of many artworks in the museum, these sculptures are not willing to be shelved. Rather, they look like they are fresh from production.

To produce this pair of sculptures, Henke completed an extensive residency at the Swiss Kunstgiesserei Sitterwerk, a foundry famous for, as well as among, top-notch sculptors. The foundry’s clients tend to drop off a sketch, and trust the facility to do “the rest.” Then the artist shines at the opening. There’s nothing unusual, let alone unethical, about art production companies, which have mushroomed with the maturing of conceptual art. But the exceptionality of Henke’s hands-on involvement, working the facilities, investing her very self, provokes meditation on how art’s break from the artisanal sits with the “idea of late German sculpture” of the show’s title. Henke further underscores her own bodily investment in her choice to scale Ayşe Erkmen’s Endless Knee (according to Le Corbusier’s Modulor standard) to her height of 1.829 meters.

With Mom (after Henri Laurens), a sculpture in a series of smaller-scale busts cast in bright purple, the artist goes a step further in restituting the body to the work by including her family’s faces as portraits—or rather, portraits of the family as artists. And here too, by way of the titles, Henke references male artists, sculptors, and stonemasons like Henri Laurens (1885–1954), the Cubist and Orientalist, whose elongated flattened portraits resemble disembodied African masks. The bodily concerns of Mom (after Henri Laurens), to some degree, seem an attempt to reconcile the male lineage of deformation with matriarchal matters.

Resting her case, the bust sits on the second step of a white abstracted staircase. The staircase-support is a sculpture in its own right, modestly forming a stage-prop-like middleground between white cube wall and Cubist bust, and thereby also providing an infrastructure which intrigues. The steps are a part of a series of white abstracted pedestal-sculptures, designed to elevate as well as to echo the show’s idea of kinship. Archetypical architecture on the one hand, sculptural syntax on the other, they form a late descendant in the genealogy of the plinth.

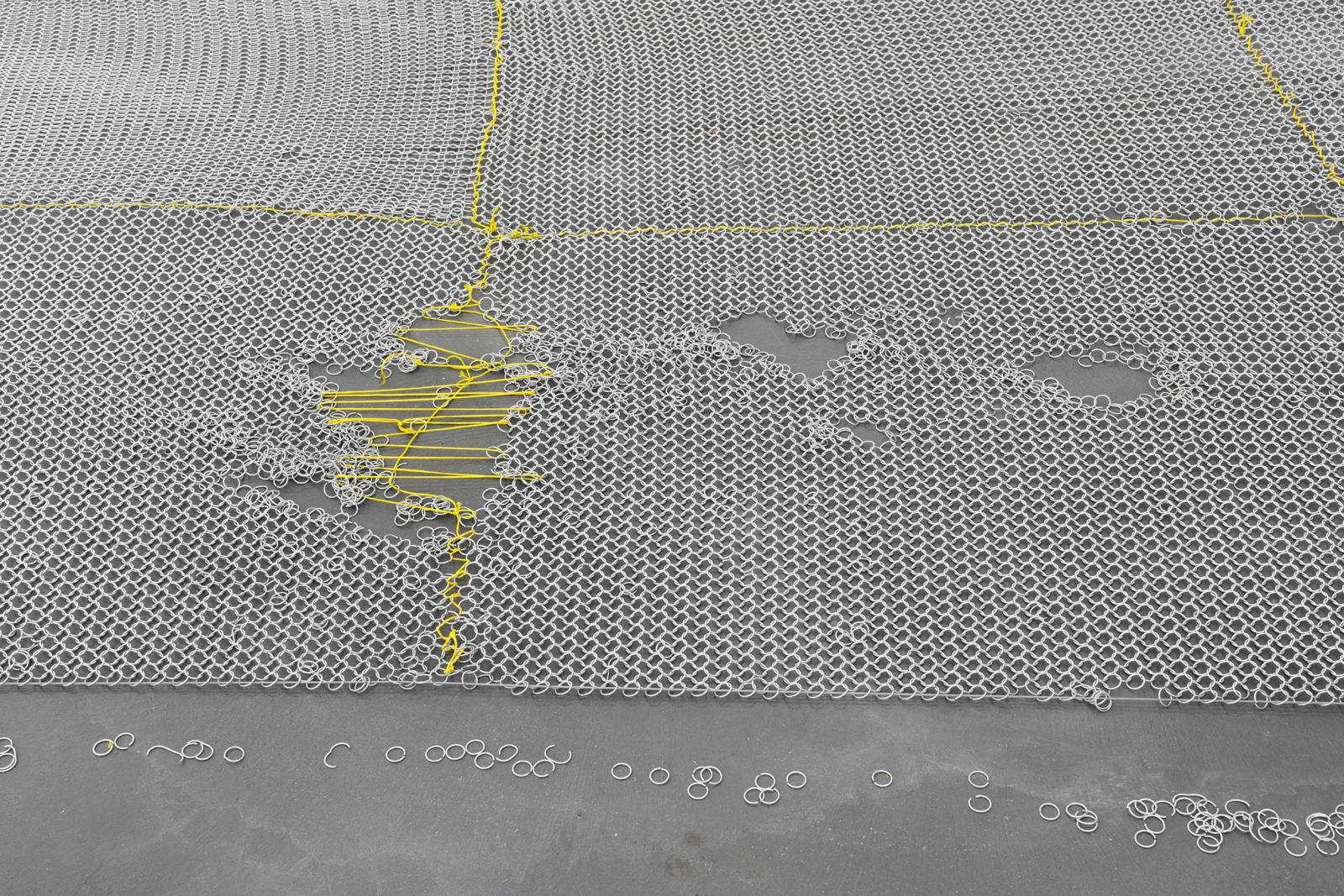

Vulnerable in the Moment of Control is the show’s most apparent juxtaposition of the paternal Modernist vocabulary of sculpture with contemporary feminist practice. It is a juxtaposition as movement, which according to guest exhibition curator Fabrice Stroun, reperforms the double bind of mobility: the sculptural requirement of perception in motion as well as personal development in the sense of social mobility. It further demonstrates, I would add, the two-fold nature of political mobilization: for the personal remains the political always. The work references psychoanalyst Wilhelm Reich’s notion of “character armor” which Henke transposes to a web of hand-knitted patches of metal rings—a feminism of steel versus stitch. A kinetic piece: the chainmail seems to creep back and forth on the gray concrete floor—like a crushed serpent. Or like the moment you realize the run in your shirt just when you were trying to look “serious.” It’s that sense of creeping dysfunctionality that truly nuances Henke’s works’ tight technicality and critically twists the narrative of “the People of New York” with the “Idea of Late German Sculpture.”

Julia Moritz is a curator, critic, and mom based in Zurich and Berlin.