Kiyan Williams on forging your own path, community, and “Notes on Digging”

Brooklyn-based writer and entrepreneur Kiarrah L. Beverly speaks with artist Kiyan Williams about forging your own path, community, and Notes on Digging.

Kiarrah L. Beverly: It was such a pleasure working with you at Recess in Brooklyn; I wanted to bring it back home and kick this off with a shout-out to Stephanye, Camilo, and Allison for connecting us. First and foremost: What are your pronouns?

Kiyan Williams: My gender pronouns are they, them, theirs, and she, her, hers. I am a multidisciplinary artist from Newark, New Jersey who works fluidly across sculpture, performance, video, and wall works.

How has the experience of growing up in Newark, New Jersey, and coming out as a non-binary artist helped you shape your creative process and relationship to the art world?

Growing up in Newark, I had instilled in me a certain sense of courage and fearlessness, and that’s also related to being non-binary. But I grew up in a community where it wasn’t always the safest for me to be publicly queer and where there were no pre-existing models of who I could be in the world. I had to figure all of that out on my own. Part of that meant that I had to embrace the unknown and to not fear being a trailblazer. That also helped me forge a path as an artist because it gave me the courage to try new things, to experiment, to embrace ideas that were unfamiliar. All of that is still a part of my creative practice.

“My work is a reflection of my world. It’s a reflection of my experiences, my challenges, my struggles.”

You went to Stanford University in California, then came back to the east coast to complete your MFA at Columbia University in New York. How did those experiences differ for you?

Let’s see. Well, I was very different. When I was an undergrad at Stanford, I was like a sponge. I was eighteen. I moved three-thousand miles across the country to a place that was completely new to me. And I would just learn so much about my life, about the world. I took classes in history. I took art classes. I took classes in race and gender studies. I wasn’t an art major. But all of my experiences in undergrad—both in terms of my academic learning and the opportunities I had to intern with and be mentored by other artists—ultimately helped me realize that working in performance and visual art could be a real profession. And after I finished undergrad, I decided to move back to the east coast, specifically to New York, in order to cultivate my creative practice as an artist. I wanted to cultivate my artistic practice around other Black, queer, and trans people, and for me, that community was in New York City.

You’ve stated in the past that you consider your ability to be yourself at all times to be one of your greatest accomplishments; as a Black non-binary artist, why is that important to the work that you do?

My work is a reflection of my world. It’s a reflection of my experiences, my challenges, my struggles. For me, practicing, self-determination, being able to exist in the world on my own terms, allows me to bring a certain type of authenticity to my work. It allows me to present my voice and my vision with clarity and with concision such that my point of view is my point of view and it’s unique, but it’s also unwavering. I’m not going to shift that because of external forces.

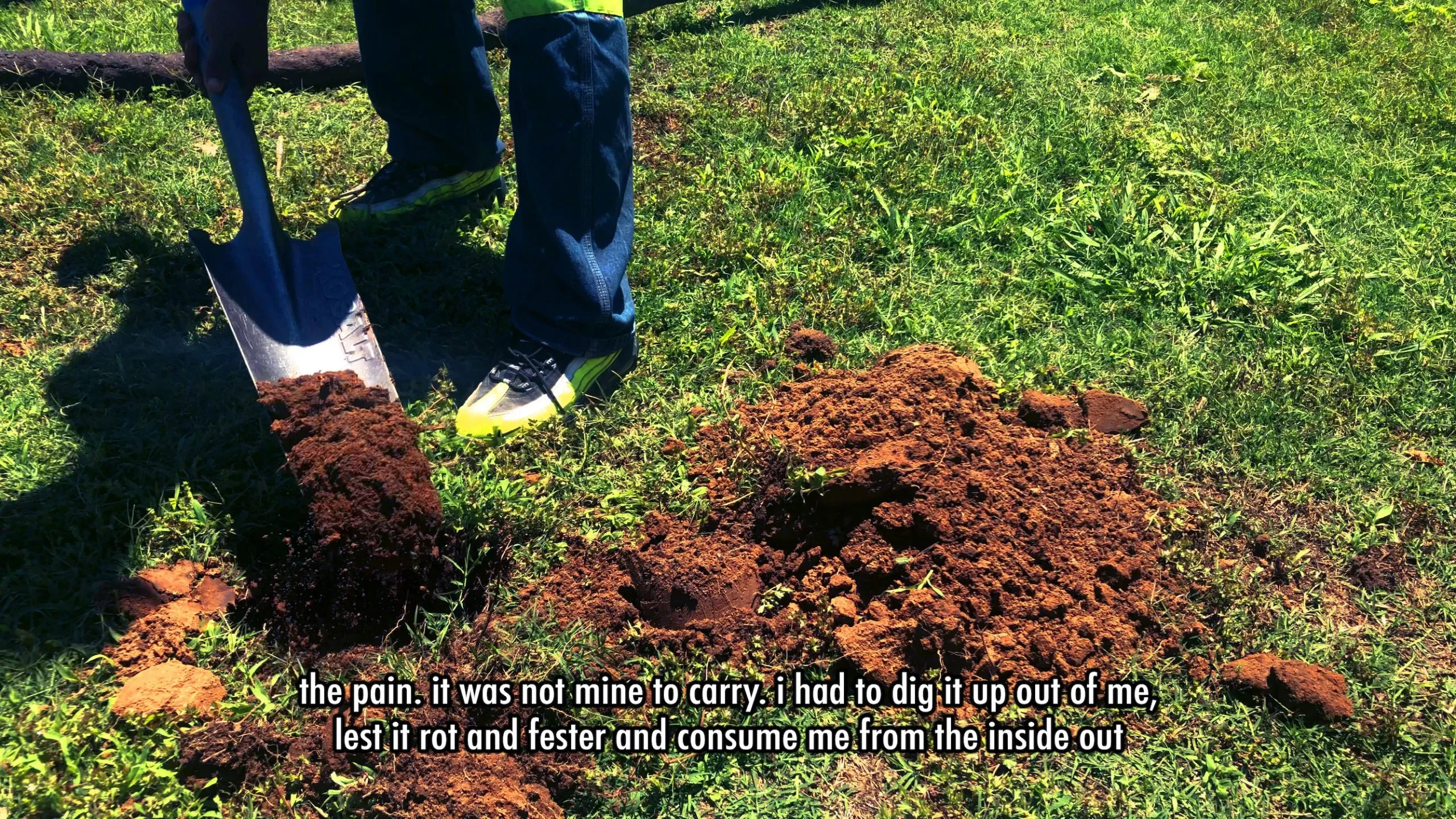

Your video Notes on Digging, which premiered at The Shed last year, has been described as “transforming your need to dig in and make art out of the earth into a ritual of care.” Can you talk a little about that piece?

I created Notes on Digging when I was living in Richmond, Virginia. I had been doing a lot of research on the history of the slave trade in Richmond specifically. I was making Reaching Towards Warmer Suns (2020), a public art work to memorialize and commemorate the lives of enslaved Black people who were kidnapped and brought to Richmond, Virginia. During the process of making that public sculpture, the pandemic started. For most of that time, much of the world was in quarantine. I made that sculpture during quarantine and what it revealed to me was that being in nature and working with the earth was a way to work through the feelings of isolation that we were all experiencing. Also, working with earth, being in nature, going on hikes, and going on walks was a way for me to process both the recent trauma brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic and the historical and ongoing trauma that Black people in America experience.

Working with you at Recess on the project something else (Variations on Americana) (2020) was an amazing experience. Helping you fry the American flag for the piece “Flag Fry” was something I will never forget. You’ve shown me we can fry more than a pork chop. In a sense, I can say—I got down and dirty for my country. What was the concept behind frying the American flag and what was the message you wanted to convey?

Exactly. No, totally. I got the idea of the flag fry during the summer of 2020, when there were uprisings across the country and across the globe against anti-Black violence. I wanted to extend the tradition of Black American artists who have appropriated and manipulated the American flag in order to reveal or critique structural and systemic inequality. I was also thinking about cooking as a way to transform materials through a kind of chemical process in which you take something and you manipulate it by seasoning it, frying it, baking it, et cetera, in order to transform it into something different or edible.

“I was also thinking about cooking as a way to transform materials through a kind of chemical process in which you take something and you manipulate it by seasoning it, frying it, baking it, et cetera, in order to transform it into something different or edible.”

But I was specifically interested in the method of frying, because when you fry something, you change the texture, the skin, the coating of it. I started to fry flags and I was really attracted visually to these bubbles that would form on top and the way the flags would char in different places. That kind of became a metaphor for the distress that was happening in America. America was like this boiling, kind of festering, charred thing. I wanted to stage an intervention into the sort of romanticized, idealized notion of America as the land of the free and the home of the brave, which we all know is more myth than it is fact or more ideal than it is reality. And so frying the flag, distorting it, manipulating it, was a way for me to communicate that.

How did you find out about Recess?

I found out about Recess through previous artists who did sessions there, who were friends and mentors of mine. I went to a session by the artist Jacolby Satterwhite back when Recess was still in Soho. Then I remember being really engaged in sessions by Black Art Incubator and Sable Elyse Smith. What I appreciated about all of those Recess sessions was how they catalyzed and brought in community around an idea. I really appreciated that element of social practice—that ability to be with people as a kind of collaborative, a collective art-making experience.

Like a lot of events in the world, my session at Recess was impacted by the pandemic. I’m so grateful to have worked with the team at Recess in order to reimagine what my session could be, not only to fit my individual needs during that time, but also to imagine ways to contribute to the collective well-being of my community of artists in New York. I used the studio as a rudimentary space where I could just work through ideas, and I ended up changing the name of my session because I wanted to respond to the necessary changes that were happening in the art world. Following critiques about the art world’s elitism, its anti-Black racism, and transphobia, I wanted to make a space that was more accessible, more equitable, and safer for non-white, non-cishet people. I had to do something else because the world was something else and needed to be something else.

“Following critiques about the art world’s elitism, its anti-Black racism, and transphobia, I wanted to make a space that was more accessible, more equitable, and safer for non-white, non-cishet people.”

What is one piece of advice you would give to other LGBTQIA+ millennials?

This is a question that I think about often. I would say my advice would be to listen to your intuition and your internal voice. And by that, I mean that if you know your life, and you know your experiences, then you know what you need in order to thrive, in order to be whole, feel loved, and feel supported. Don’t be afraid to listen to that voice because the world will try to diminish and silence that voice. Don’t be afraid to ask for help, even though that can often be really challenging because of shame and fear. Though there are people who may not want to help you, there will be at least one person who wants to help and support you.

What is one piece of advice you would give your younger self?

You know what? When I was young, I was already self-determined, I was already a self-advocate. So instead of advice, I would want to give appreciation to my younger self because I had to figure out lots of things as a kid. I had to navigate a lot of unsafe situations alone. I had to be fiercely independent and had to do a lot of stuff on my own that typically people would do with the help of parents or a community. So instead of giving myself a piece of advice, I’m going to give my younger self a shout-out and say, “Mama, you did that.” You did your thing. You did what you needed to do for yourself. Don’t be ashamed of any of the decisions you made that you did out of survival, because you did it out of self-love. Period.

Kiarrah L. Beverly is a twenty-seven-year-old mother, writer, and business owner born and raised in Brooklyn, New York. This feature was published in collaboration with Assembly at Recess.

All photographs by Lyndsy Welgos.