Juliana Huxtable’s Interfertility Industrial Complex: Snatch the Calf Back and the Pursuit of Desire

“Agriculture has always been about the modification and the projection of ideal traits. We, as humans, do that amongst each other … I think it’s really funny because some people, no matter what I do, will always think of my work as autobiographical. But I think that it’s a way of removing the psychosis of what is happening. I think that’s just a way of making it ahistorical and contemporary, but I don’t think it’s actually what it’s about.” – Juliana Huxtable

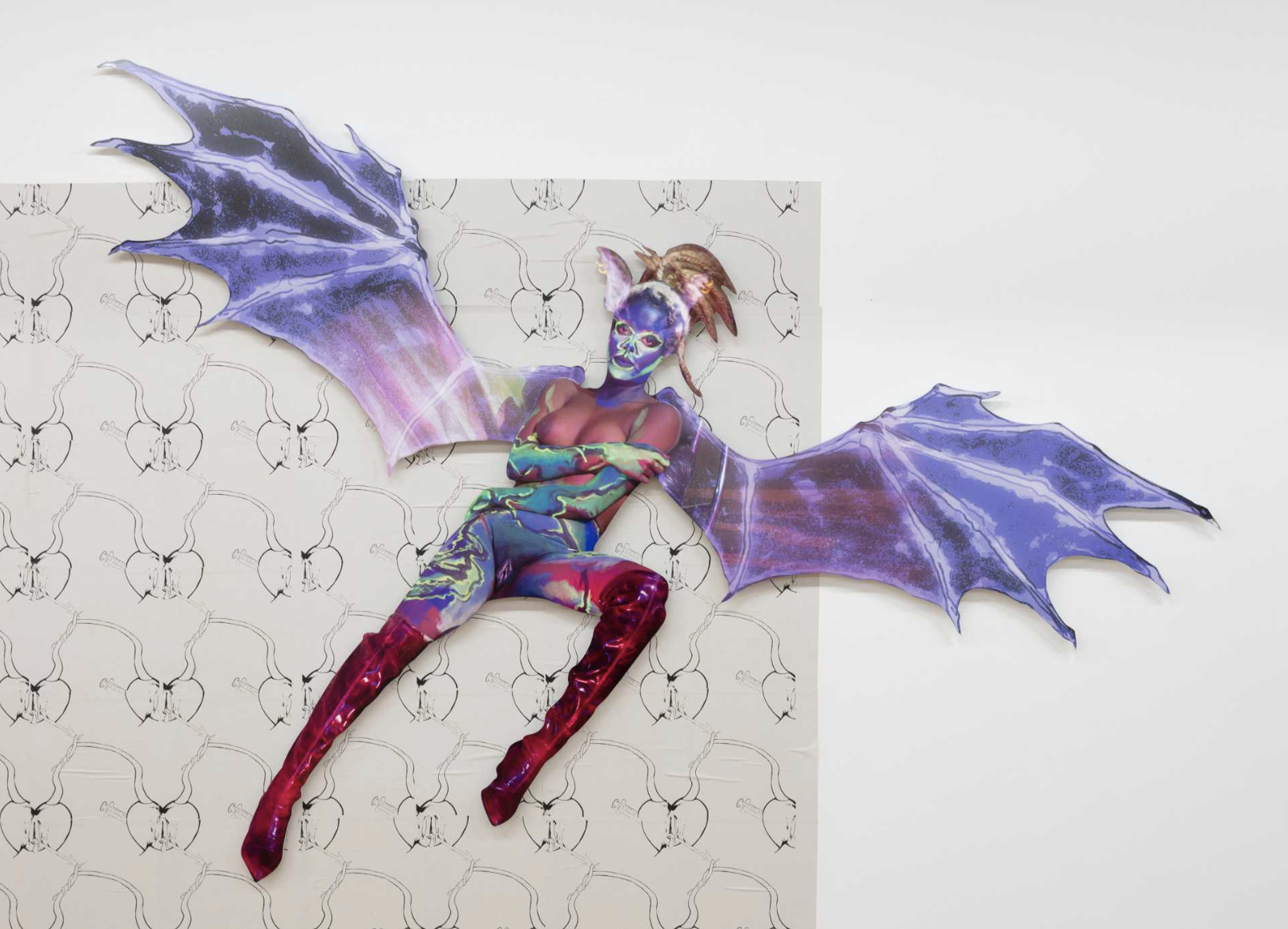

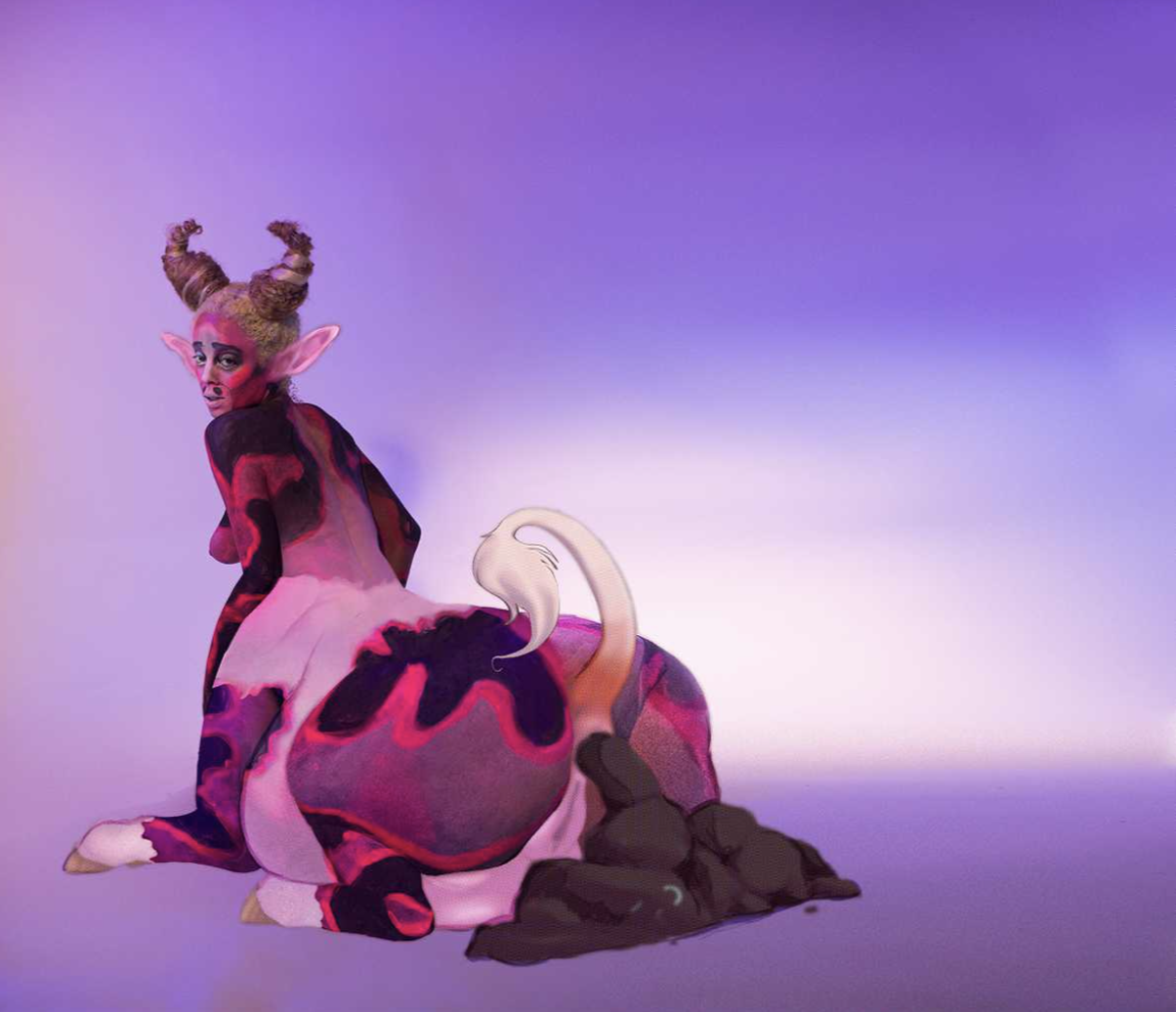

Juliana Huxtable’s exhibition Interfertility Industrial Complex 5 at Reena Spaulings Fine Art felt bleak and a bit intimidating upon entry, as though I’d walked into a space I shouldn’t be poking around in. In the center of the gallery a row of commercial bathroom stalls stood open before me, ULINE-phallic installation style, with each unit hosting discrete images, both still and moving, of hyper-sexualized beings. This base atmosphere was punctured intermittently with warm zaps of color; on the wall hung prints of neon-fuschia-hued photos showing more of these fantastic characters as they reached out in the atemporal, electric non-space of a pastel seamless studio backdrop.

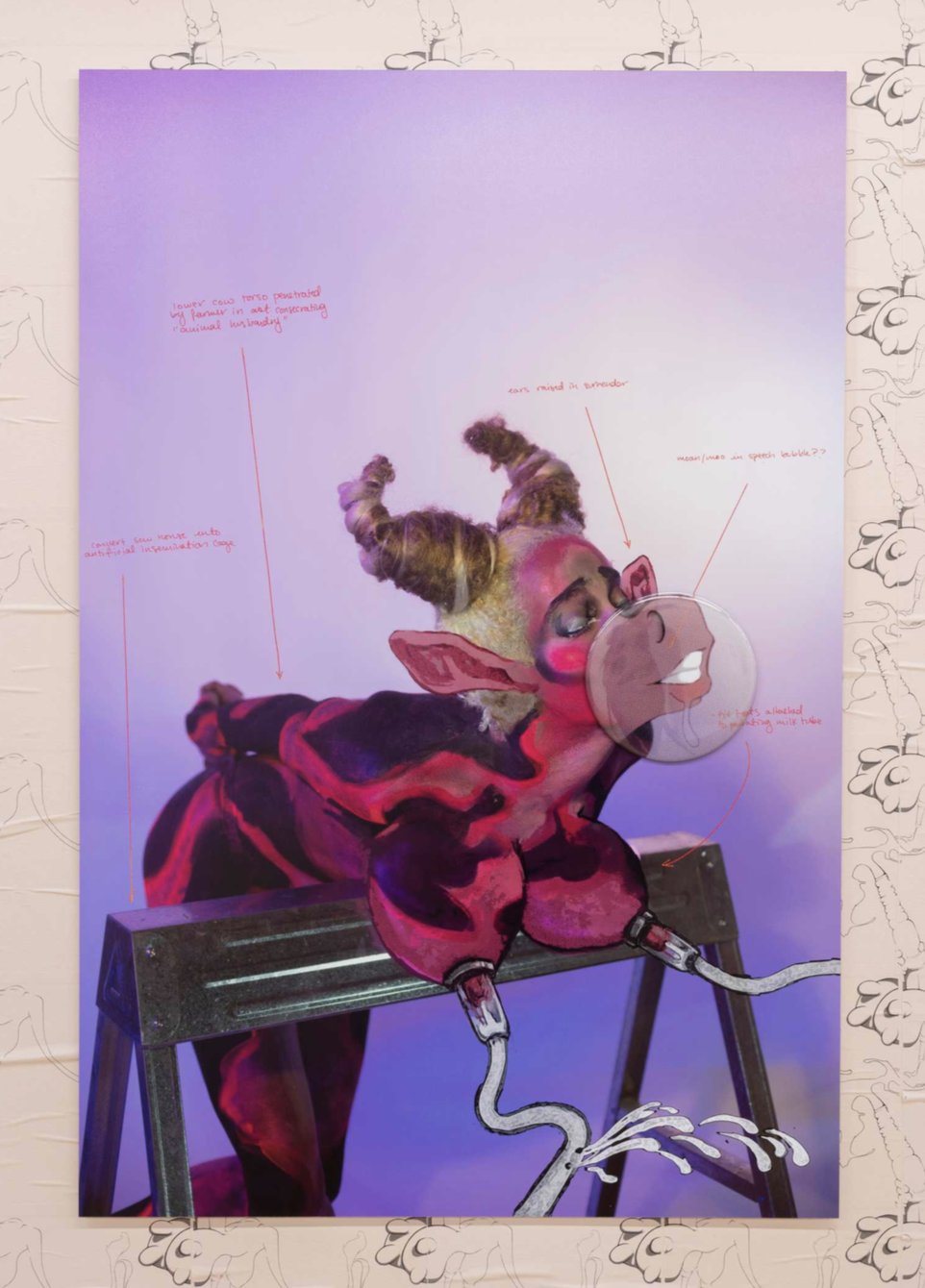

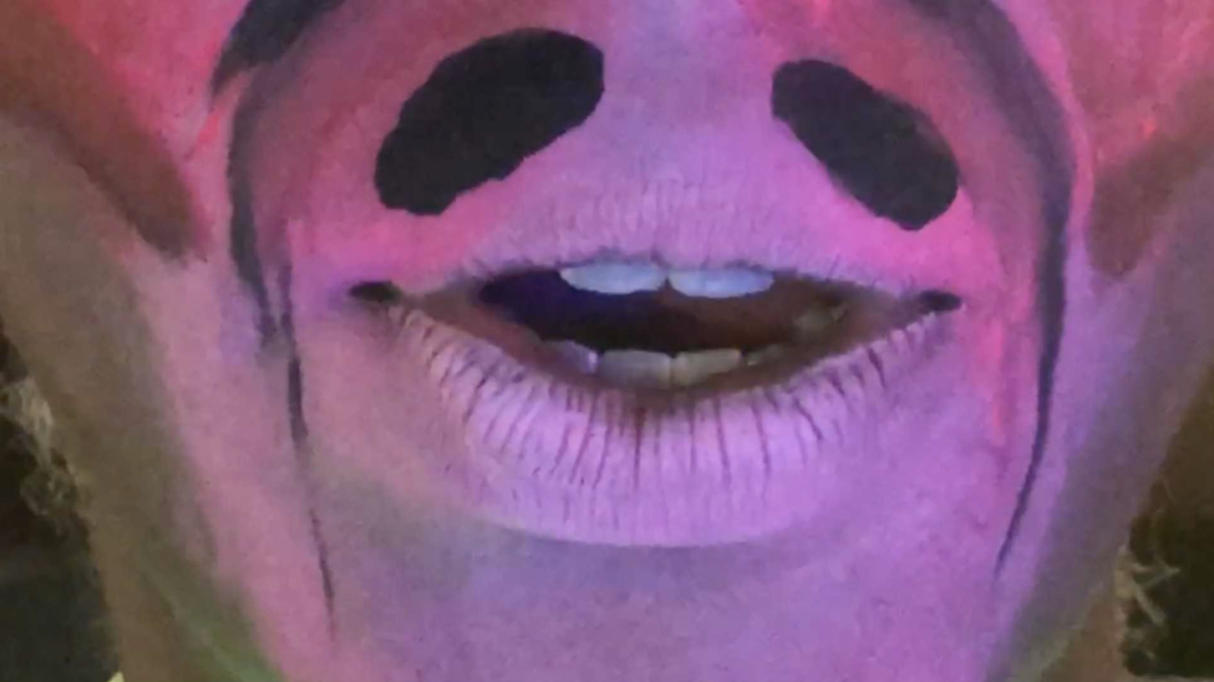

They all resemble animals. Some have multiple udders, while others have hair that curls into horns. Still others feature snouts or spots and stripes that blanket bulbous appendages, and many of these dolled up performances-of-being are accessorized by handwritten annotations. Here they are, whoever they are, trying to tell you what’s up, casting gazes of all sorts—lonely, confident, wild, hungry, in pain.

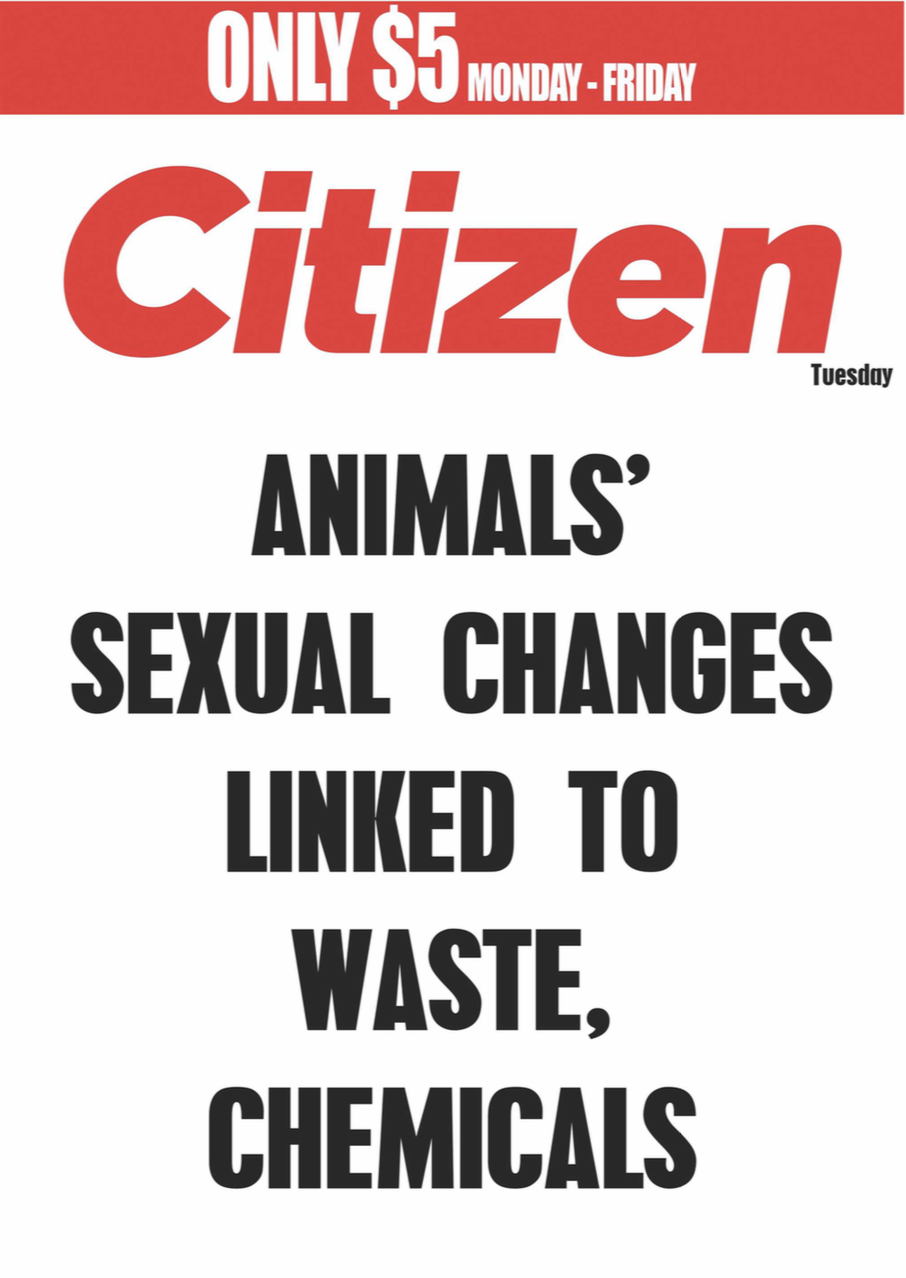

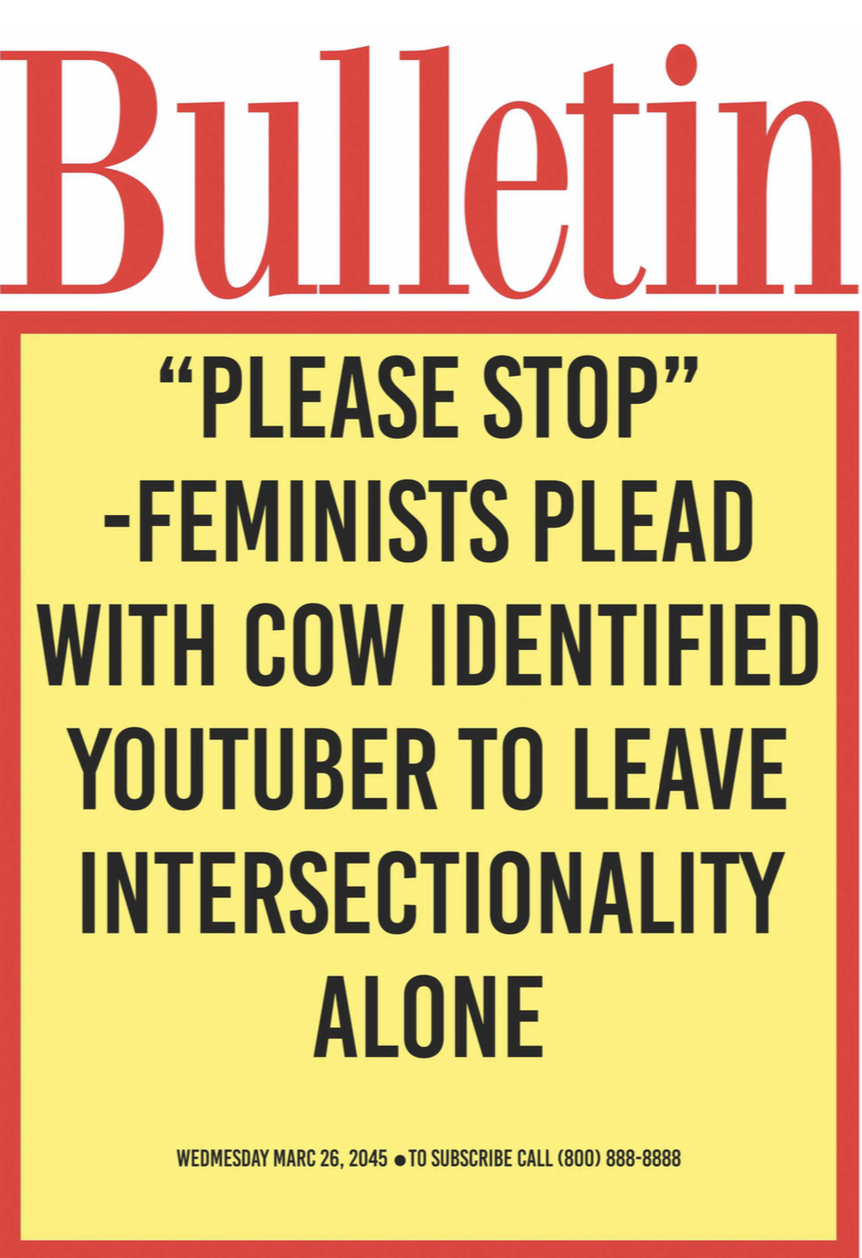

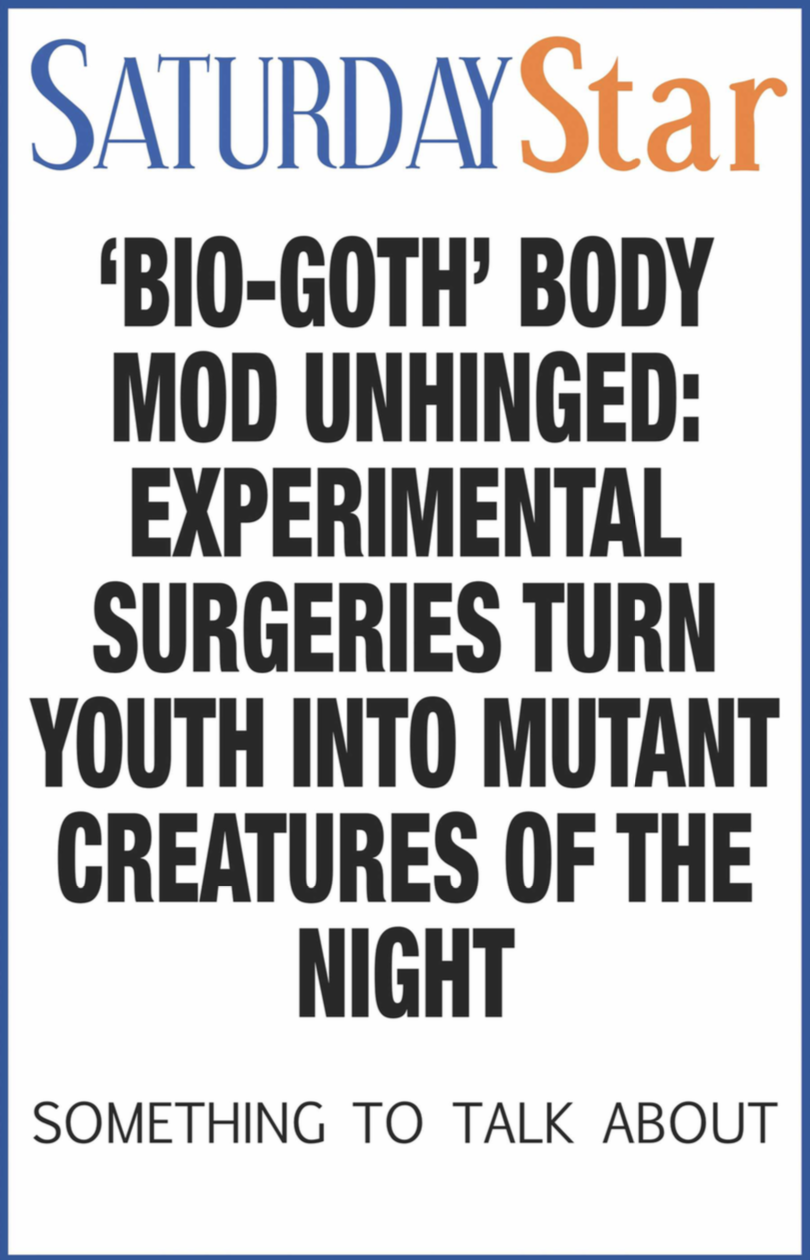

As though their beings can’t be constrained within two dimensions, the flesh of their surfaces is augmented with the addition of pinback buttons that splooge out of the image and into our space through adornment. Everything here is decorated, accentuated, and heightened, trying to communicate—extra, but with a contemporary organicness in its sensibility, like drawing one’s finger across the screen to quickly blur away a blemish in a selfie while riding the bus. Stapled directly to the wall, garish posters scream out click-bait style headlines, making my peripheral vision feel like a sidebar, and, the longer I explored, the more I began to realize that through the proliferation of information in the room, coupled with the heterogeneity of its forms, Huxtable had created a malleable, accessible, and playful vibe.

Intrigued by the multiplicity of setting, as well as the wry hacking of editorial and folklore formats, I met up with Juliana on FaceTime to talk about some of her personal experiences with industrial agriculture, and how language finds form. Selections from that conversation are included below.

We, as NYC/LA/CDMX/Euro.jpg art viewers, are conditioned to seeing anarcho-aesthetics and punk staging rituals either dominating or creeping about an exhibition’s presentation. It takes some genuine reading of the glyphic yet composite layers of Huxtable’s forms to understand what she is communicating here, and that is not because of a shortage of power on her part but, rather, is more indicative of the easily-locatable-embedded-reference ways we shape, read, and critique art and language these days.

Huxtable begins always with writing: all 2-D, 3-D, moving-image works, and their installation, emerge for her from texts she writes, and we can see the effects of this quite well in the shifting volumes within the show. In IIC:STCB, form does not feel stuck, but rather like a vessel or conduit for language, and ultimately, meaning.

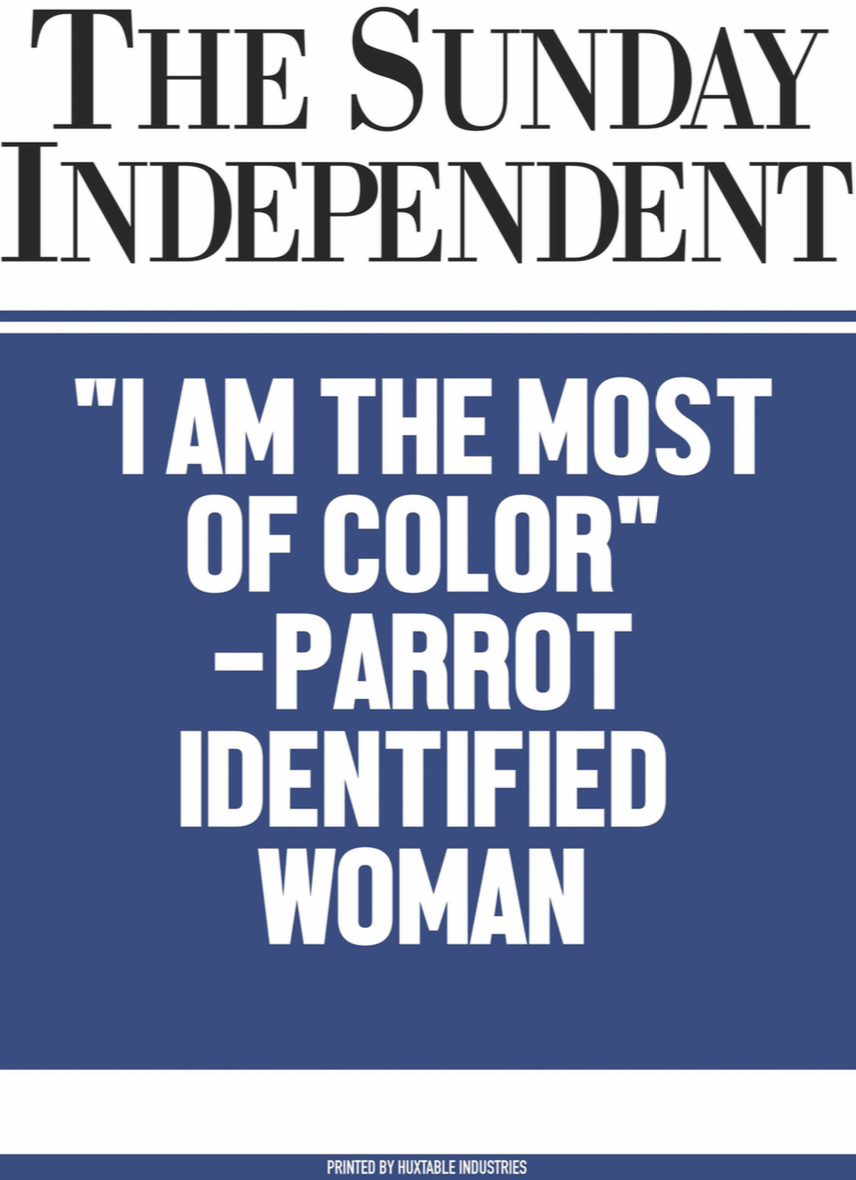

While the punk stylings of the show do indeed serve as a wise subcultural-appropriation perversion, they also are the most organic format for Huxtable’s artistic language. Recently, text on clothing has gone from fashion’s last resort to a main means of signification. Similarly, wheat-pasted posters are no longer footnotes on the city’s pages but are now installed by expensive advertising teams for high-end retailers selling hype-luxury hybrid wares. However saturated we are with these forms, they retain functionality because the message remains captured in bold-face, legible fonts. Confusingly, in spite of both their ubiquity and elevation, these forms still register as “sub-cultural.” Traditionally punk modes of design and visual communication will indeed keep reappearing, precisely because of their sexy efficacy, and Huxtable has chosen them for this reason. A fuccboi may approach on the sidewalk, and no matter how much we don’t want to extrapolate what his hoodie is blasting in sans serif, we can’t wire our brains to just not read it.

In previous exhibitions, Huxtable had taken a strategic, essayistic approach to visual forms born of her writings. In IIC:STCB, pages upon pages of notes began to transform into more opinionated, subjective formats; a narrative was developing, and a story was going to be told. As Huxtable puts it, in this show, the “Texas really came out.”

This past summer, Huxtable visited her hometown of Bryan–College Station, Texas, which, as she explains, is a “psycho, super conservative small town, but with the ability to amplify and perform with the scale and magnitude of a Texas football college.” The town is home to Texas A&M (which stands for Agriculture and Mechanics), and is one lens through which the fable in IIC:STCB can be seen: a culture shaped by NFFA, Hearne High School, high achievers, the Bible, raising livestock, rodeos, and cowboy hats. It is a place that holds itself up as a moral ideal, where any minor transgression against family values is sure to be confronted with Super-Sized gusto. This is a place where, as Huxtable describes, you enthusiastically labor to design, for instance, a machine for McDonald’s to more efficiently grind meat. Here in Bryan–College Station, the scaling of mutilation and its performance is so vast, it renders as white noise. No wonder a third nipple seems shocking.

“Agriculture was everywhere in Texas. I remember my class would take a trip to a farm every week with the intention of ‘raising an animal.’ At the end of the year, this animal would then be sold at the County Livestock Show, and everyone would participate in that process.”

Bearing witness to the simultaneous terror and joy of producing these animals, while still being a developing human-animal oneself, is no insignificant experience. Huxtable does not simply re-present the horrors of the current state of food production, though; in IIC:STCB we find her splashing in the puddles of this industry’s waste, highlighting the contradiction of ethics in raising an animal as something which is touted as simultaneously natural and exceptional; of the earth, and also of Capital.

In IIC:STCB, we find a free play between function and ornament, pleasure and terror. Orifices and appendages multiply, and indeed, why not? If our bodies are being augmented by GMOs, vitamins, and prescriptions, while produce and livestock are being bred of shockingly small gene pools to endlessly encourage “ideal traits” in the marketplace, why not then push further to really accommodate desire? Think about the hygiene of your energy. If you’re eating a cheeseburger, is your body not only working to digest the nutrients in the sandwich, but also the souls of the various cattle it’s ground of, and various beings these cattle once ate? What about the trauma of the insertion of the farmer’s fist into the cow’s anus to determine pregnancy? What about the trauma of the calf during the spectacle of its own sale at a state fair? And, of course, how do these traumas affect production? If the cow is unhappy, symptomatically, the milk will show its suffering. While PTSD may be the main ingredient in most of our food, we’ve certainly shown an ability in the last century to adapt and process these traumas digestively, cellularly, and emotionally, however dysfunctionally. As such, could one not implant and perhaps work to develop the spirit of a parrot into their own psyche, as one of Huxtable’s creations suggests?

Let’s return to that row of grey metal bathroom stalls in the middle of the room. Within the center stall, a monitor is affixed to the rear wall, at eye level, above where a toilet or urinal would typically be placed. A close crop of a face painted to look like a Technicolor cow speaks slowly with a classically “story-time” seductive drawl.

The tone of the speaker (which reverberates with a chilling seductiveness at a pleasingly mild volume throughout the entire gallery) tells us to lean against the stall and tune in. It lets you know you’re going to be entertained, so, in spite of the humiliation of standing in an open bathroom stall, it’s safe to just follow along. Performatively sharing folk-lore or fable, where language is both lesson and entertainment, has a significant history and precedent in the American South (indeed, Huxtable notes that during her development of the exhibition she read Toni Morrison’s Beloved, which famously has extreme moments of bestiality, as well as a focus on oral tradition) and its mobilization in this monologue introduces IIC:STCB as a fictional space from the jump. This leads us to inquire, who are these lit beings imaged in these photos? Are they for sale and, and if so, what exactly is being sold? Is it themselves, wholly? Or do they have a specific product or service to offer? The viewer is left to wonder, as Huxtable eschews the fast-read of these stalls as sex booth, an idea she admits was at the genesis of this piece, as a way to locate the characters and their function. However, as her project developed, she began to coax out the structure’s synonym with the cages and stalls in which livestock are raised, and paralleled that concept of penned-in discomfort with the commonly accepted less-than-comfortable setting of the public bathroom as a site to relieve oneself—sexually or digestively. A banally scatological reminder of our corporeality, maybe your stomach grumbles a little as you listen to the tale of a family of farmers unfurl.

What is happening to our bodies as a result of industrial agriculture and its technological developments? How much of this is indeed related to consummating desire and developing identity? Just as one can specialty-shop and fine-tune eating habits if one wants people to know one lifts, bro, one’s body is continually augmented by invisible stranger-dangers, such as fluoride in tap water, hormones in milk, second-hand smoke, BPA in Tupperware, pesticides, fertilizers—basically everything, everywhere. In this exhibition, Huxtable chose not to isolate certain injustices and finger-wag at one singular industry and the viewer’s relationship to it. Rather, she takes up perhaps the most commonly digested space for expression and the canny espousal of ideologies: the editorial. In IIC:STCB we see two forms of editorial: the Daily Mail, New York Post-style headline in the posters, and the Dazed, “thick, quarterly-publication”-style fashion editorial. Just as the characters in her works assert themselves as bold new beings, they are subsumed into larger informative contexts. What to make of this sexy new kind of bat on a “WEMSDAY”?

It is in these editorial details, such as the publication date of “WEMSDAY MARC 26, 2045,” or the concept of a stiletto heel of a shoe being digitally altered into an impossibly walkable horn, that Huxtable throws us into the fantastic. She mobilizes techniques of dystopian science fiction (settings and forms are similar to the known present but eerily skewed), to assert that this pile-up of pleasure principles is not a warning, but rather a fanciful beckoning, because what we’re dealing with is not actually dystopian but historical. Interspecies desire, and the consummation of that desire, has certainly always existed. What Huxtable found prescient to comment upon through this show is the rage with which so many people respond to contemporary technological developments in body modification that in turn give way to hyperbolic, and what she sees as truly Romantic, developments in human identity.

“Being enabled by new technology doesn’t mean the dynamic is new, it’s just evolved. Specifically, with the questions of identity and desire surrounding the human-animal encounter … Yes, there are specific possibilities that are enabled by this technology, but the technology doesn’t actually mean that this dynamic, this core set of things that are being expressed through this new possibility is contemporary, totally ahistorical and has no precedent. That means that trans species’ identity would cease to exist.”

Take, for example, the annotated figure in BAT 1, which shows us that a mall-goth is today a purchasable identity and one you can purchase fast. The twenty-first century has clung to significations from the previous one, while simultaneously embracing their mutability. Anyone can get a goth look (pale goth, Victorian goth, Tribal goth, cybergoth, hippie goth, traditional goth—you can even take a quiz to see which one you are) but, just as quickly as you can have this look shipped to your door, you can also leave it behind. So, hands in the air to those who choose to mutilate and modify, to those who go full bat ear, and connect it to the “wing of [their] post-punk eye[liner].” Could the multiplication of vaginas potentially satisfy those unable to conceive? Or would it just be way more fun in foreplay? Perhaps, with a multiplicity of organs, they could become liberated from their use value? Who knows, but it’s a hell of a lot more romantic to consider than a velvet choker from Fashion Nova.

“There’s nothing Romantic or passionate about buying an on-trend piece, but to give yourself new ears, is really, quite Romantic, be it subcultural identity, or personal identity. … The real Romantics, the new-new Romantics, are actually the people that are committed to body modification. That gesture is about Romantic submission to a weird ideal, an ideal way of being in the world, an ideal way of structuring identity in a way that piercing, tattoos, plugs, can be seen as a move away from the frivolousness of just fashion, in the face of countercultural signifiers in that way being totally ephemeral.”

Parallels between industrial agriculture as breeding to refine genetics so that a few ideal traits can be infinitely replicated, and a current crop of gallery artists severing identity politics from history, as both industries (agriculture and culture) are cornering markets through ahistorical approaches, can indeed be drawn through Huxtable’s blatant refusal to neatly address timely questions.

As we grow up and develop our personal identities, it is often the local legends and folklore of our home-town culture that guide our decisions as to whether we follow the course or break the mold. Are you going to seriously read the pamphlet the nurse gave you in health class, or are you going to cut it up to make a flyer for your basement show? Huxtable’s exhibition offers her audience a vivid chance to revisit this culture and lore, and unpack the misconceptions and myths that still today ooze into our definitions of ourselves, our desires, and our drives.

Whitney Claflin is an artist and writer living in Brooklyn, New York.