Juliana Huxtable on Crisis, Conspiracy, and Collapse

Juliana Huxtable’s first solo show, A Split During Laughter at the Rally, opened last month at Reena Spaulings Fine Art, New York. It’s rich with text and graphic works that combine and recontextualize language mined from some of the deepest rabbit holes of the conspiracist internet. The interview that follows took place at Huxtable’s Bushwick studio, and visits some of the show’s key concerns: political agency and powerlessness, the mutability of political style, and the crisis of authoritative references in the era of networked information technology.

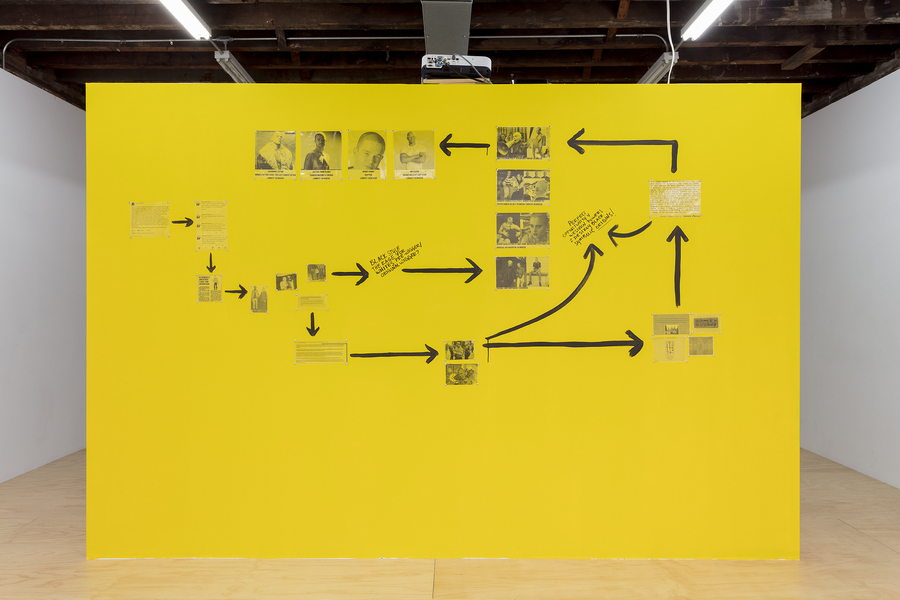

Tess Edmonson: Two pieces in the show thematize white radical appropriation of Black culture and Black aesthetics: a video, A Split During Laughter at the Rally (2017), which follows a group of post-Trump Bushwick protestors, and speculates that their protest chants appropriate rhythm from Black culture; and an untitled wall piece with a diagram charting a kind of genealogy of skinhead style, where skinheads’ appropriation of signifiers from Black pop culture gives way to skinheads’ explicitly neo-Nazi ideology. What drew you to represent these political transactions?

Juliana Huxtable: For me, cultural appropriation is a really interesting, furtive place to jump from. It’s one of the most heated debates in these micro-wars that happen online and in digital culture. I wanted to think about how to display that kind of collapse and these manic narratives. Especially thinking about the legacy of Black culture and the relationship between Black visual culture and what’s seen to be political or not.

I knew what I wanted the show to be about before Trump was even a serious candidate. I pushed the show back significantly. Part of it is specific to Trump, but the Trump aspect of it just became more topical. I think that the way that we are processing political agency and how that might be executed or enacted is really linked to questions of how we’re processing information and systems of information as well as questions of cultural production. I felt like part of the inefficacy of the way that people are processing or dialoguing around politics was thinking of it as if it’s this isolated thing. People say that young people aren’t really turning out to vote, and writing it off as if people aren’t engaged. I think people are engaged, but the ways that they’re engaging are different. The way that someone wears their hair is as politically loaded as whether or not someone votes, maybe even moreso than whether or not someone votes for Hillary or Donald or whatever.

I started thinking about whether I could map out how we’ve gotten to this point of apathy and crisis. Part of it, I think—which is why I wanted to focus a lot on information and how information is circulated—is because of a crisis of original reference. How do you operate in a world in which we don’t really have a primary source? Not that there ever has been one, but at one point there was at least the illusion that there was. I think everyone is in this sort of epistemological crisis. How do you form a political narrative grounded in what’s real?

That is essentially the starting point for our conspiracy. One of the essential cornerstones of conspiracy is that the lack of evidence, the lack of proof, is proof of something in and of itself. If no one is talking about it and we can’t find any information and there’s one original reference on aliens, it’s obviously because they’re trying to hide it from us. It’s a kind of weird logic, but I think that in the situation that we’re in right now, it’s an interesting place to think from because it’s way different than either apathy or nihilism.

The exhibition gathers together a huge range of different registers of online political discourse, which drew out, for me, parallels between methodologies of activist thought and conspiracy theory that I had never thought of. In both cases, you try to know about systems of power that you don’t have access to. You read the signs and symbols, and try to make a narrative out of it or try to fill those logical gaps. In activism, you teach yourself and your community about how to read changes in the things you can’t access; you also do that with conspiracy theories, too.

The question of what we do, given the inefficacy of the tools and sets of information we’re given, is where the racial element I was trying to navigate comes in. I think that a conspiracist’s mode of thinking is kind of inherent to the Black experience. It’s really clearly illustrated by the Black American political legacy where, based on the history of America, you know that these structures are obviously mediated against you. And now we have the language to describe that. What, at one point, was someone being paranoid about the idea of slavery being enacted in the prison-industrial complex is now a language we can use.

In order to have that language, it took people being like, “I know that this is true. Nothing around me is verifying this. None of the encyclopedias, none of my history books, none of the news reports, nothing around me is verifying what I ultimately know to be true. I know that this is literally slavery in a different form. I am not given the possibility to navigate that, based on the systems that are laid out in front of me. I’m going to take the leap of faith and insist on that and create languages surrounding that. I don’t have the information, resources, or infrastructure that will verify my instinct. I’m just going to insist on it.” It’s not the same thing as a conspiracist’s way of thinking, but I think it’s similar. Something about the idea of conspiracy was kind of inherently Black to me in that sense.

There’s a series of posters in the show, where different things you’ve sourced from the internet are all kind of amalgamated into a single political graphic, despite their different ideologies. There’s one piece, for example, The Feminist Scam (2017), that has text on the top describing how women’s high school basketball is a scheme that makes its players gay, and below, there’s text that says, “the feminist scam: intersectionality, Cointelpro, female masculinity and the destruction of the Afrikan family.” On top of this are buttons that say “misandrists united” and “cross-dressers for Christ.” The presentation flattens these different sources that you’re taking from, in the same way that the internet flattens the different discourses they belong to.

For The Feminist Scam piece, the starting point is this whole strain of thought coming from a place of wanting Black liberation. You have the Black feminists—which isn’t a singular movement, but you can say there’s a larger ideology there, which takes intersectionality as a starting point. It’s also pushing a lot of prison reform that influences Black men. Then you simultaneously have this strain of naturalist Black liberation concepts, pejoratively called “hotep.” They have twisted the narrative where now, all of a sudden, the white culture’s exploitation of Black people is actually the imposition of an effeminized homosexual agenda that seeks to effeminize Black men and masculinize Black women. Black feminism is actually a secret plot to undo the advancement of the Black race, which is all cinched around biological reproduction tied to very legitimate claims of emasculation, genocide, and legacies of rape. It’s starting from a very legitimate point, but then you end up at, “kill all gay people, all Black feminists are the devil.” I find myself watching these videos, and I can understand where they’re coming from even though they want to burn me alive.

Maybe instead of just writing this all off as conspiracist trash—not that I would want to indulge these people because a lot of them are just homophobes and misogynists—but thinking through that logic and entering that space is, to me, a conversation that’s much more relevant to how Black people are thinking about questions of Black liberation and questions of Black politics. Now everything is being read as a secret white homosexual agenda. Navigating the conspiracies … it all kind of collapses. They all collapse into each other at different points. Maybe I want to push to that collapse point, like, “let’s try and over-identify with it and push it all in.”

How did you decide on the graphic and typographic elements to represent the language in the show?

I was thinking about the contemporary failure or crisis of the countercultural aesthetic. What is a leftist aesthetic? How can I look at something and, based on what the visual signifiers are, know that it is for or against a certain thing?

I got really fascinated with Emory Douglas in terms of what’s informed my idea of what is political imagery. I look at Communist Party, Working Party, Black Panthers posters, and I’m like, “this is something that has very clear political aim.” I would just assume by virtue of how it’s presented that it’s leftist. I think that the legacy of things like that has influenced and lingered in ways that I wasn’t even privy to until I started going into the conspiracy rabbit holes because all of those papers are coming from a sense of being oppressed politically, being misrepresented politically, being pushed out for whatever reason. What’s interesting about a lot of conspiracist agents, thinkers, whatever, is that they have a similar view of themselves. You have an InfoWars person who literally feels like everything around them is designed to suppress, control, and emasculate every aspect of their existence. The language that they use and the indignance that they feel is very similar to a late-sixties radical politics. Those aesthetics and that language have even bled into conspiracist culture.

I think explicitly confronting how paranoia manifests into these weird conspiracists’ political fantasies, you learn a lot. Conspiracy theory is all-consuming, to a certain degree. Once you start, it implies this total logic. Each conspiracy has its own tenets that repeat themselves. Ultimately it’s kind of viral in a weird way.

Paranoia also makes you receptive to the mutability of the symbols around you, which is I think one of the things that’s really radical about it. Obviously, people choose to stop using that logic at a certain point. The skinhead piece was this opportunity to be like, “how can we apply this mode of thinking if I’m staring a white Nazi in the face?” Everything is unstable in that sort of mindset. You immediately have to start backtracking. “What is missing from this picture? What does that absence suggest? What is real in this situation, and what should I take or not take for granted??” I had just thrown these things out as premises because I thought it would be cool, just in a playful way, to construct the logic for this show. I didn’t know the history of skinheads. I didn’t know that they came from rude boys and it was white people in Britain hanging out with Jamaican immigrants. Not that that narrative is a literal arc. But it was totally accidental.

Tess Edmonson is a writer based in New York. She is associate editor of Flash Art and assistant editor of art-agenda.