In Excess of Speech

Is speech ever really free? In Western ideology, the concept of “free speech” has historically had a definition at once too narrow and too loose, with boundaries and implications that apply to some but not to others. Here, writer Zoë Hopkins draws from two moments in history—one artistic, one cultural—to call into question the false freedoms of any speech. Hopkins probes these two “historical scenes of muteness,” as she calls them, to argue that acts of binding and silencing can expose, or even upturn, the interests of those who hold political, economic, and socio-cultural “power.”

— Ebony L. Haynes, 2024 EIR

“In the beginning there were no words.”

– Toni Morrison, Beloved

⁂

If everything that my flesh knows could be given in language, would the bubble that holds my lexicon swell to the point of bursting? Would my dictionary collapse under its own weight? Would I ever again feel the free fall of wordlessness?

I don’t know. All I know is that there is so much to be silent about, that I cannot imagine living in a body that can comfortably and completely inhabit language, that so much of the matter that lives in my bones cannot be uttered or signified. This inheritance is an obnoxiously loud one, and it is always stealing my tongue from me.

⁂

We tend to think of the practice of “silencing” as a foreclosure of speech that is either inflicted on the silenced subject or intentionally instigated by them (e.g. refusing to snitch to the police). But then there is the silence already given in language itself, the silence that begs us to stretch—or entirely reconfigure—the definitive scaffoldings on which the modern concept of censorship is built: the irreducible silence imposed on our tongues and on our psyches by the weight of the past and the accretion of catastrophe therein. The catastrophes that precipitate this arrest and cessation of speech antecede the very idea of “free speech” and then obliterate it. They make the ground of language open up, fall out, and give into failure.

When faced with the incomprehensibly violent historical forces that have made blackness, language ineluctably freezes and then evaporates; signification can only buckle and break. It is from this zone of what cannot be said that blackness will always haunt (“free”) speech and so, too, silence: articulation meets an impossible challenge when confronted with the unspeakable brutality and terror of enslavement and its wake, of anti-black modernity and its continual procession into new frontiers of cruelty.1

“But then there is the silence already given in language itself, the silence that begs us to stretch—or entirely reconfigure—the definitive scaffoldings on which the modern concept of censorship are built: the irreducible silence imposed on our tongues and on our psyches by the weight of the past and the accretion of catastrophe therein.”

The shadow of these unspeakable matters lies beneath language and dismantles the West’s ideological aspiration toward “free” speech. We can trace the shape of this shadow in two historical scenes of muteness that unfolded in close succession at the edge between the 1960s and ’70s: the first in Chicago, during the 1969 trial of Black Panther party co-founder Bobby Seale, and the second on a New York City bus during Adrian Piper’s 1970 performance of Catalysis IV.

⁂

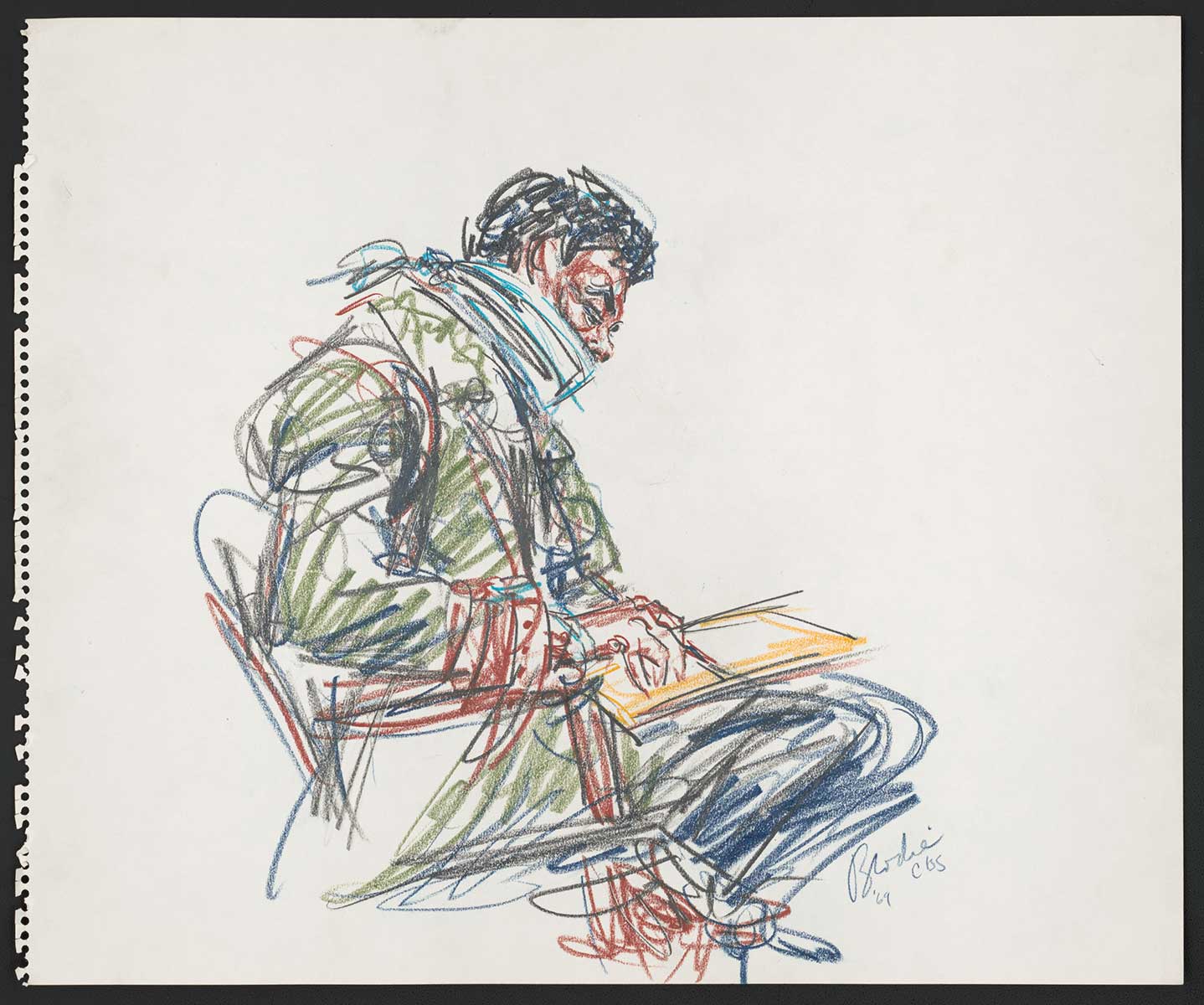

Consider a sketch by courtroom artist Howard Brodie picturing a moment in Seale’s trial. The Panther is rendered in a rush of green, blue, and brown crayon on white paper. The area between his neck and nose is covered by a turquoise gag. His feet and hands are strapped—no, chained—to the legs and arms of the chair. His arms stretch against this apparatus of constraint as he attempts to take notes on a legal pad in his lap. The chains that bind his feet and hands appear to be rendered in the same shade of reddish-brown as his face, as if his very embodiment cannot be conceptualized outside of his being strapped to that chair, fixed and fettered in space.

Here is what sits in the moment that led to this image: Seale—being the clarion trumpeter of justice he was—had loudly struggled against the nefarious design of juridical racism in general and his trial in particular (he had requested a continuance due to the fact that his lawyer couldn’t be at the trial, but the request was denied without reason). Julius Hoffman, the presiding judge, called upon the court marshal to “deal with [Seale] as he should be dealt with in these circumstances,” and ten minutes later, he emerged from an anteroom, limbs and lips restrained.

It goes practically without saying that the trial of Bobby Seale was part of a project insidiously engineered to keep certain black mouths shut: there is no shortage of things to say about the brutal lengths that American intelligence agencies went to in their ardent endeavors to silence the Panthers and other radical groups, killing some and imprisoning others. This image in particular readily lends itself to a reading within the threads of discourse that unfurl around the history of censorship during the Black Power movement: if there is any metonymic symbol of the censored voice it is the gagged mouth. The cloth covering Seale’s lips in that courtroom is a par excellence signifier of the perverse impossibility of “free speech” under the unfreedoms of American empire and its juridical elaborations.

“This image in particular readily lends itself to a reading within the threads of discourse that unfurl around the history of censorship during the Black Power movement: if there is any metonymic symbol of the censored voice it is the gagged mouth. The cloth covering Seale’s lips in that courtroom is a par excellence signifier of the perverse impossibility of “free speech” under the unfreedoms of American empire and its juridical elaborations.”

But there is something in the picture that beckons us to a place deeper and denser than what the political imaginary of “free speech” can hold: writhing underneath the surface of the gagging is the binding. The chains. The history of bound captivity which is indexed in that metal around Seale’s limbs, and which travels from the hold of the ship to the chain gang to the contemporary carceral state. There is a co-constitutive relationship between the trampled voice and the chained body, a bind between the binding and the gagging, which led Judge Hoffman (who is but one embodiment of the larger, even more vicious entirety of racism’s political schema) to apprehend Seale’s right to utterance as utterly violable, or more fundamentally, not given as a right at all.

The spectacle of Seale bound and gagged in the courtroom is, in other words, an inherited one: a summary of a longue-durée of spectacles wherein blackness—bound and immobilized—was produced outside of the zone of political freedom and sovereignty in which the architecture of “free” speech is built. What becomes of “free” speech when you are speaking from chains, when the chains have already rendered you mute?

As Black feminist theorist Hortense Spillers illuminates in “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book,” when African bodies were chained together in the holds of slave ships crossing the Atlantic, they became black flesh, an indistinguishable, racialized, and commodified mass voided of “any hint or suggestion of a dimension of ethics, of relatedness between human personality and its anatomical features” signifying “total objectification, as the entire captive community becomes a living laboratory.”2 Along with the transformation from body to flesh came a transformation at the very core of communicative and semiotic order: flesh does not speak, rather, it is always-already spoken for by “layers of attenuated meanings … assigned by a particular historical order,”3 namely the orderings of enslavement and racialization. The Middle Passage inculcates a grammar of being in which blackness cannot speak for itself: the sign of the black human is rendered incoherent, muffled, buried beneath a set of fixed meanings that are externally imposed and enfleshed by white supremacy.

“The spectacle of Seale bound and gagged in the courtroom is, in other words, an inherited one: a summary of a longue-durée of spectacles wherein blackness—bound and immobilized—was produced outside of the zone of political freedom and sovereignty in which the architecture of “free” speech is built.”

The grammar that Spillers writes of is complicated—but ultimately thrown into sharp relief—by a certain fact that we don’t see in the courtroom sketch (listen to the image, though, and perhaps you can hear it)4: the gag that the court marshal initially wrapped around Seale’s mouth was too thin. It fell short of its purpose, and his voice, albeit muffled, could be heard calling out: “I want my right to speak on behalf of my constitutional rights.” Then the court marshal simply came back with binding tape, several thick layers of which were used to re-guarantee Seale’s silence. The image of this moment projected in my mind’s eye is a crushing one: here is Seale, going to war with this endeavor to silence him, crying out repeatedly and with everything he had in pursuit of the right to speak. Then bound even tighter. A bound spectacle of muted flesh.

The drawing of Seale gives way to a chasm, an uncrossable gulf—wide with senselessness— between Seale bound to his chair and the judge seated on his bench, a void into which meaning is swallowed up and evaporated. For Seale, his vocal attestation to his supposed right to speak was an extension of his fiery commitment to struggle. For the judge, these words could not signify with any coherent meaning. They were a mere disturbance to the proceedings of the law. Pure noise. Incommensurable with the dialectics of recognition. Received by the judge as bound flesh, Seale certainly had no “right to speak” in court. His muted flesh could neither speak nor be spoken about: it is the unspoken and unspeakable rule around which governs that courtroom, which governs American governance itself. His fleshiness was, in Spillers’s words, “the primary narrative,” the narrative by which all the discourse in that room was determined.5

So, we end up in a bind between the words that Seale was prevented from speaking, the regime of unspeakable terror that produced this foreclosure of speech by fixing blackness outside of the right to speak for itself, and the resulting unintelligibility of a black person who insists—in the face of this very regime—on being free. The hurriedly drawn surface of this image of Seale tells of a man denied his right to free speech. But when we cut into its core and linger there, we must also face that Seale never had the right to speak. So too must we face the unspeakable machinations that subtend this non-vocality, those centuries of manufactured abjection that made Seale’s gagged mouth possible and which nullify the discourse of “free” speech.

⁂

In the summer of 1970, less than a year after Seale was bound and gagged before the court in Chicago, a twenty-two-year-old Adrian Piper got on the bus in New York City with a towel stuffed in her mouth, cheeks bulged out to accommodate this strange addition of matter. This activation—Catalysis IV—was part of a broader body of work collectively titled Catalysis, a series of public performances in which the artist engaged in unusual, shocking, and seemingly absurd acts of self-transformation aimed at testing and then shattering the limits of normative comportment and rational engagement with others.

Piper titled her performances Catalysis to illuminate, in her words, how “the work is a catalytic agent… promot[ing] a change in another entity (the viewer) without undergoing any permanent change itself.”6 Stated otherwise, the sheer abrasive force of her unyielding presence as she publicly performed acts completely foreign to the fabric of normativity was meant to instigate new terms of engagement between herself and those she encountered during the performance, to shock people into a more rigorous attention to the metaphysical contours which hold our relation to and alienation from each other. Imagine beholding the overstated weirdness of this spectacle. Imagine not knowing it was a performance. Imagine what kind of questions it might spark for you about who she was and why her body was configured that way. None of this could be overlooked or passively received, all of it solicits a reckoning with Piper’s presence.

“Stated otherwise, the sheer abrasive force of her unyielding presence as she publicly performed acts completely foreign to the fabric of normativity was meant to instigate new terms of engagement between herself and those she encountered during the performance, to shock people into a more rigorous attention to the metaphysical contours which hold our relation to and alienation from each other.”

In particular, spectators could not ignore the streak of violence—however absurd—in Catalysis IV: though Piper does not wear an expression of pain or discomfort in the photographic documentation of the performance, her filled mouth is a kind of self-inflicted metaphysical wound, an injuring of her own ability to speak. In an interview with Lucy Lippard, Piper underlines this dimension of the performance, framing the Catalysis performances as an intentional violation of her corporeal coherence: “You know, here I am, or was, ‘violating my body’; I was making it public. I was turning myself into an object.”7

There’s a disarming willingness to forgo the conventional markers of selfhood in Piper’s claim here, a disavowal that starts with the body and ends with subjectivity itself. The “violation” of Piper’s body not only catalyzes the shock and awe of the public, it also catalyzes a shift in her whole ontological schema: a shift from the position of the subject to that of the object. Piper gives this concept a more elaborate framing in Talking to Myself: The Ongoing Autobiography of an Art Object, a series of writings published alongside the Catalysis performances. As the title suggests, the text makes the case for the (performance) artist as not only generative of the art object, but as ontologically equivalent to the art object itself.

In Catalysis IV, it is Piper’s muteness that buttresses her self-objectification: her intentional foreclosure of speech renders her inaccessible and opaque, withholding her (or she withholds herself, rather) from the conventions of inter-subjective communication and from attendant apparatuses of social interpretability and legibility. In this refusal to occupy the kind discursive space that is imagined as commensurate with subjectivity, she encases herself in the category of objecthood. Thus, in the single fell-swoop of the stuffed/silenced mouth, Piper gives herself over to and for the spectator as an art object precisely by withholding—from this same spectator—access to her subjectivity as an artist. She conveys her objecthood in and through impenetrable, mute presence.

The spectacularity of Piper’s muteness, then, cannot be read separately from the internal metaphysical transformation she undergoes: from the performer to the very thing being performed. As she writes in Talking to Myself, “… now I become identical with the artwork … as an art object, I want to simply look outside myself and see the effect of my existence on the world at large.”8 By making her into an artwork, the corporeal “violation” that is Piper’s stuffed mouth—that is her muteness—brings the art object into the material world, into the throes of relation, and into the artist’s enfleshed relation to the world. An artwork qua artist is an artwork unfettered from the ideal of the pure and transcendental—that hermetically sealed zone where art is lodged and held apart by Western metaphysics. By identifying with the muteness of (art) objecthood, Piper executes what we might think of as a liberation of the art object, unfurling the fullness of its capacity to live and act “in relation to the rest of the world.”9

“It is Piper’s muteness that buttresses her self-objectification: her intentional foreclosure of speech renders her inaccessible and opaque, withholding her (or she withholds herself, rather) from the conventions of inter-subjective communication and from attendant apparatuses of social interpretability and legibility.”

A quiet attack is launched through Piper’s self-objectification, a mutilation not only of the boundaries between artist and artwork, but also of the boundaries around subject and object that hold modern Western metaphysics together. She refuses the violent romance of the subject, renounces the putative authority of its knowledge, and insists instead on the knowing object. She is not only performing objecthood, but sourcing her power from objecthood: it is as an object—a mute presence observed and absorbed by others—that she molds her environment and what she can do in it, it is as an object that she enters the world of verbs. Thus it is through objecthood that she comes to know those who encounter her in the theater of her performance, and additionally, comes to know how and why her presence affects these spectators.

There is, in my view, a black ethos in Piper’s recalcitrant valorization of the power of objecthood, in this dis-arrangement of the subject and its presumed correlation with Knowing and Being. As Fred Moten writes in the oft-cited opening lines of his book In the Break, “the history of blackness is a testament to the fact that objects can and do resist.”10 For Moten, this resistance of the object is a performance of the object: it lives in gestures, arrangements of the body, in utterances and their withholding.

A reading of Catalysis that follows Moten might conclude that Piper performs not only as an object, but as a black object that resists. Notwithstanding Piper’s racial ambiguity, and even her ability to pass as white, when she insists that she is “turning [her]self into an object,” the white supremacist machinations that have grafted objecthood onto blackness cannot be evacuated from the frame of our attention. The towel in Piper’s mouth calls attention to these histories, to the rift they have constructed between blackness and agency. But it is not the equation of blackness (or her black self) with objecthood Piper is rebelling against: rather, her performance is a disavowal of the regulative powers that subtend this category, a refusal of the very idea that subjecthood signifies a place in the world while objecthood signifies the lack of such a position. She is not performing subjugation, rather, she is performing her resistance to the world and its logos, to the ordering of objecthood and subjecthood therein. Finally, in claiming the mantle of the object for herself, Piper—as mute as she may be—is also able to name and speak for herself, and thus, crucially, to contravene the grammatical and semiotic orderings which Spillers reads in “Mama’s Baby.”

⁂

We can’t know whether Piper had seen that image of Seale bound and gagged up in that courtroom a year prior (although it’s not unlikely that she did, given the magnitude of Seale’s trial). But the kinship between these two moments—between Piper’s stuffed mouth and Seale’s gagged one—begs a reading of one in the context of the other. When we look at the spectacle of Piper’s performed muteness and see the residues of Seale’s brutally enforced muteness on the courtroom floor, Piper’s performance shifts into a different register. The coerced foreclosure of speech in the theater of the courtroom becomes bound up with the volitional foreclosure of speech in the theater of the public art performance.

Can anything bridge the anxious gap between these two spectacles of muteness? How is Piper’s silent articulation of her right to opacity recast when we think about the silencing of Seale’s articulation months prior? On what grounds does the racialized artist “speak” when all speech is anteceded, determined, and circumscribed by the metaphysical precepts of black flesh that led to Seale’s gagging?

“When we look at the spectacle of Piper’s performed muteness and see the residues of Seale’s brutally enforced muteness on the courtroom floor, Piper’s performance shifts into a different register. The coerced foreclosure of speech in the theater of the courtroom becomes bound up with the volitional foreclosure of speech in the theater of the public art performance.”

There is a world of obvious and irreconcilable difference between Piper’s gagged mouth and that of Bobby Seale’s, and I won’t take up space by elaborating the basics of this differentiation between an activist who has been gagged by a state and an artist who has gagged herself. Instead, I want to attend to the more subtle differences that structure this juxtaposition. For one, there is a semiotic question of form and shape: the full stuffedness of Piper’s mouth takes on a shape of a profusion, signifying abundance, while the gagging of Seale’s mouth bears the shape of absence, signifying deletion or negativity. In this sense, Piper’s muteness appears as an excessive extension of her corporeality, while Seale’s corporeality is reduced to his bound muteness, his lack of being.11 Stated otherwise, what Piper is performing is not merely muteness, but the transmutation of a lack into an affordance, a wearing and superimposing of privation as a sign of excess on her own body.

This observation around the morphology of absence/presence thrusts us back into the theater of interpersonal relations in which each spectacle is involved. Piper’s towel protrudes outward into the public sphere, into the orderings of sociality to which her performance was addressed, or more accurately, which her performance disrupted. Seale, meanwhile, was silenced because his voice was a disturbance to the ruthless orderings of the court, because it is not supposed within his purview (the purview of flesh) to disrupt the juridical machinations which produce and police the distinction between fleshy object and embodied subject. Put simply: while both Piper and Seale enacted some kind of disruption, for Piper, self-imposed muteness was the cause of the disruption, while for Seale, externally imposed muteness was the consequence of disruption. Piper’s performed silence and self-objectification was, in this sense, a flipping of the script from which anti-blackness and its laws unfurl. Designed to disturb the conceits of the subject and its domain of normative sociality, her blackness, her black objecthood, the black muteness of her objecthood, stage a mutinous disarrangement of the American grammars of flesh and body, object and subject.

Piper brings the unspeakable, unspoken matter of her objecthood—fleshy and black—into the open, into the performed terrain of art. She inhabits, unrepentantly, the obdurate swell of her silence, the antinomian bloat of all that is signified when the social falls away and yields to immediate presence, when the freedom to speak gives way to the freedom to decline speech, to buck against interpellation, to refuse to fall in line with subjecthood. Or: she refuses to refuse her objecthood. She clings to its spectacularity, stuffs herself with its amplitude, lets it puff up and spill out from her. She is art because of her flesh, not in spite of it. She is mute, and hers is a muteness that exceeds the question of speech.

Zoë Hopkins is a writer and critic based in New York. She is currently working on her MA in modern and contemporary art at Columbia University, where she researches conceptual art of the black diaspora. Her writing has been published in The New York Times, Frieze Magazine, The Brooklyn Rail, ArtReview, Jupiter Magazine, and Hyperallergic, as well as several exhibition catalogs.

NOTES

1. Here, I am indebted to the work of thinkers and writers including Saidiya Hartman, Jared Sexton, and Toni Morrison, whose speech “Unspeakable Things Unspoken: The Afro-American Presence in American Literature” has helped me think the term “unspeakable.” See: Toni Morrison, “Unspeakable Things Unspoken: The Afro-American Presence in American Literature,” Michigan Quarterly Review, August 6, 2019, https://sites.lsa.umich.edu/mqr/2019/08/unspeakable-things-unspoken-the-afro-american-presence-in-american-literature/.

2. Hortense Spillers, “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe: An American Grammar Book,” Diacritics 17, no. 2 (1987): 68.

3. Spillers, “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe”: 65.

4. See Tina Campt, Listening to Images (Durham: Duke University Press, 2017).

5. Spillers, “Mama’s Baby, Papa’s Maybe”: 67.

6. Adrian Piper, “Talking to Myself: The Ongoing Autobiography of an Art Object” in Out of Order, Out of Sight (Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 1996), 32.

7. Lucy Lippard and Adrian Piper, “Catalysis: An Interview with Adrian Piper,” TDR: The Drama Review 16, no. 1 (1972): 78. https://doi.org/10.2307/1144734.

8. Piper, “Talking to Myself,” 34.

9. Piper, “Talking to Myself,” 42.

10. Fred Moten, In the Break: The Aesthetics of the Black Radical Tradition (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2003), 1.

11. The phrase “lack of being” (manquer à etre) is borrowed here from Lacan, who says in his writings on Freud: “Desire is a relation of being to lack. The lack is the lack of being properly speaking. It isn’t the lack of this or that, but the lack of being whereby the being exists.” Jacques Lacan, The Ego in Freud’s Theory and in the Technique of Psychoanalysis, 1954-1955, ed. Jacques-Alain Miller, trans. Sylvana Tomaselli (New York, N.Y: W.W. Norton & Company, 1991), 223.