(Im)possible Baby Case 01: TWO MOMS

With advances in science and technology, the sociobiological implications of sexual orientation have given way to ethical and political exhaustion. The historical anxieties of biopolitics notwithstanding, any attempt at determining the root of homosexuality in innate traits or behavioral characteristics rubs up against the eternal tragedy of science as every step toward inflexible truth meets frustrating inconsistencies. The question concerning same-sex attraction (a paradigm of this paradox) has outlived its usefulness and its response remains inaccessible. Catherine Malabou’s current work on the recent discoveries in epigenetics (the study of how experience alters the genetic code) and the way new information concerning genes affects our perception of biological life raises further challenges to science’s ceaseless self-involvement with the “hard” data it generates.

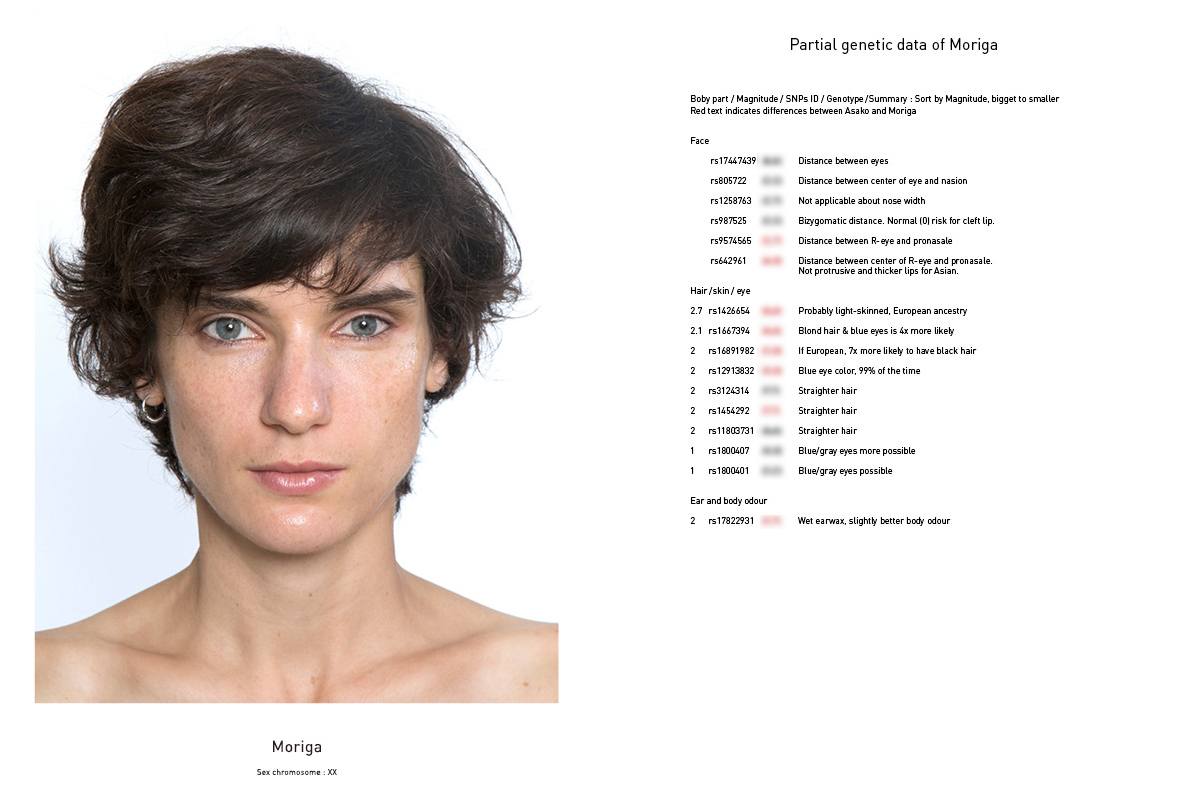

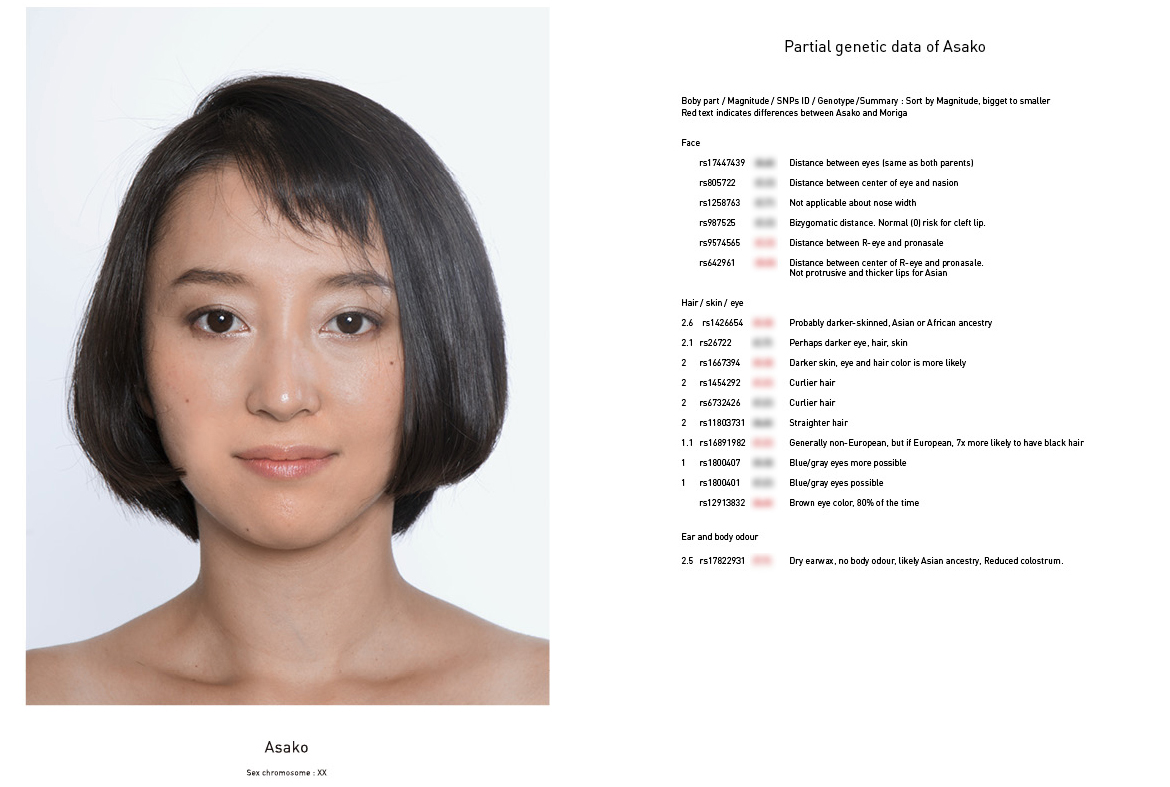

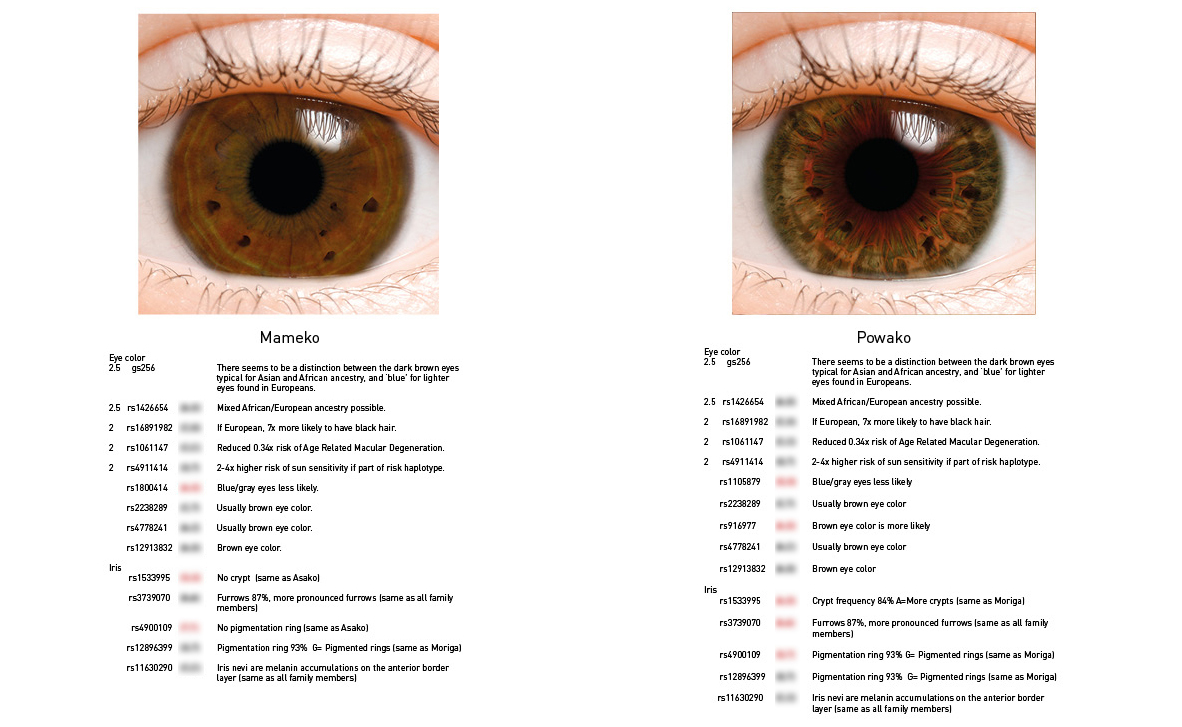

A recent project by Ai Hasegawa, a researcher at MIT Media Lab, entitled (Im)possible Baby, shows how the feedback loop of scientific “progress” tries to channel itself most productively in a niche market. A purely speculative production, (Im)possible Baby employs existing software and scientific data to stimulate public discourse on the cultural and ethical weight of emerging biotechnologies that could eventually allow same-sex couples to have their own, genetically related children. The project takes the DNA of two homosexual women using 23andMe, a privatized genetic information acquisition service that provides personal genetic reports through home saliva-gathering kits. The information obtained from these kits is then interpreted using SNPedia, an online index of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) existing in the human genome. From there a software is used to cross-reference the women’s data with the index to generate an individualized report about her genetic attributes like propensity to disease based on the presence of specific SNPs in her genome.

Hasegawa combines both phenotype and genotype data to construct a photo album of the family and their hypothetical dynamic. As she demonstrates in the above breakfast scene, “daughter Mameko sniffs coriander and makes a disgusted expression. She possesses gene rs72921001 (C;C) which makes her more likely to think coriander tastes like soap. Daughter Powako eats an asparagus and looks at the viewer in mischief. She possesses gene rs4481887 (A;G) which makes her more likely to smell the metabolites in her current meal later in her urine.”¹

At its core, Hasegawa’s project isn’t all that speculative. Designer babies were first created in 1989 via pre-implantation genetic diagnosis (PDG) allowing scientists to swap “naturally” occurring DNA sequences with synthetic ones to alter the sex of an embryo. PDG is a recent component of assisted reproductive technology that has resulted in vitro fertilization and cryopreservation, among other biotechnological advancements. Altogether, existing dependence on assisted reproductive technologies casts new light onto perceptions of the tabula rasa.

As a component of its invocation of ethical discourse, the project emphasizes an existing trend to privatize well-being through science and technology. Initially, PDG procedures were designed to ensure basic, safe human development. Mitochondrial donations, to take one example, acted as a preemptive measure against passing on genetically-inherited mitochondrial diseases to offspring. But the science behind these procedures, developed under the auspices of medicine, is no longer limited to necessity. In tandem with the increasing availability of cosmetic surgeries, the ethical permissibility of assisted reproductive technologies falls flat in the face of market demand, real and potential. Although data is divided as to whether there is a significant income gap between same- and opposite-sex couples, the conversion of non-medical science into luxury services is gaining significant traction by the sheer existence of a demographic that is willing to pay enough for what it wants. And while the fictive children’s physical and behavioral similarities to their parents could make talk of the gay agenda actually provocative, such a face-value focus concerning the project deflects from its gesture toward shaping the human race via the desire for a genetic extension.

Transhumanist dreams aside, the curators of future generations are not the guarantors of ideological analogues. When asked about Hasegawa’s project, Japanese researcher Tomohiro Kono claimed it ethical to elongate life but unethical to create it, fearing the manufacture of a generation born without consent (as if anybody with heterosexual parents asks to be born). In 2004, Kono and his team of researchers created the first bi-maternal mouse. According to Kono, the goal of the study was to “discover why sperm and eggs were required for developments in mammals,”² rather than to develop a method by which same-sex human couples could conceive children. But in his take on Hasegawa’s project, Kono overlooks the naked truth (which hits close to the delusion that arises out of popular theories on accelerationism)—that technology cannot do the thinking for us. The inability to create or assert full control over a human brain means that even if the modern Prometheus defies the laws of nature, she still isn’t the midwife to sentient automata.

The role technology will continue to play in influencing the human genome remains as inconclusive as the science it seeks to uncover. As it stands, (Im)possible Baby relies on the fallible interpretation of genetic data by computer software, and can yield unpredictable results. The gene editing process involved in crafting designer babies has already shown to be imprecise, resulting in off-target mutations, and an unknown fraction of the data generated by 23andMe can be incorrectly interpreted in the laboratory. Our increasing dependency on mechanical analyses fails as a means of bypassing the margins of error.

If this project signals a future with a contradiction we’re not already accustomed to, it is one concerned with overcoming our ideas of what it means to evolve independently of organic reproductive processes. From a naive evolutionary standpoint, homosexuality is a dysgenic trait, meaning that it is ultimately disadvantageous for the promulgation of a species. Hasegawa’s project, however, overturns the understanding of evolution but lingers on the disquieting urge to capitalize on what was previously seen as a biological setback.

Arshy Azizi is a cultural critic interrogating the intersection of sexuality and technology, interested in the increasing influence of aesthetic theory and phenomenology on transhumanism.

NOTES

1. Ai Hasegawa, “(Im)possible Baby, Case 01: Asako & Moriga,” last modified August 2015, https://aihasegawa.info/impossible-baby-case-01-asako-moriga.

2. “Mouse Made to Reproduce Without Sperm,” National Geographic News, April 21, 2004, http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2004/04/0421_040421_whoneedsmales.