Fuccbois, Beta Bros, Softboys, Man-Children

This summer, when I was on the brink of a new relationship, my best friend sent me a series of advisory texts. “I think that Nike Frees are a red flag,” she wrote. Then: “Inability to commit is a red flag.” And finally: “Being a misogynist is a red flag.”

These warnings weren’t random. My friend meant that the kinds of guys I’d been drawn to in the past—solitary ones who constructed their power around a studied set of tastes in art, music, and, always, sneakers—used aesthetic preferences, rather than self-awareness or emotional generosity or really any meaningful interactive quality, as proof of opposition to and superiority over stereotypical bros in equivalent positions of privilege. She meant don’t be tricked by Nikes, by an aaaaarg account, by a playlist of noise music, by a studio. She meant don’t be boring.

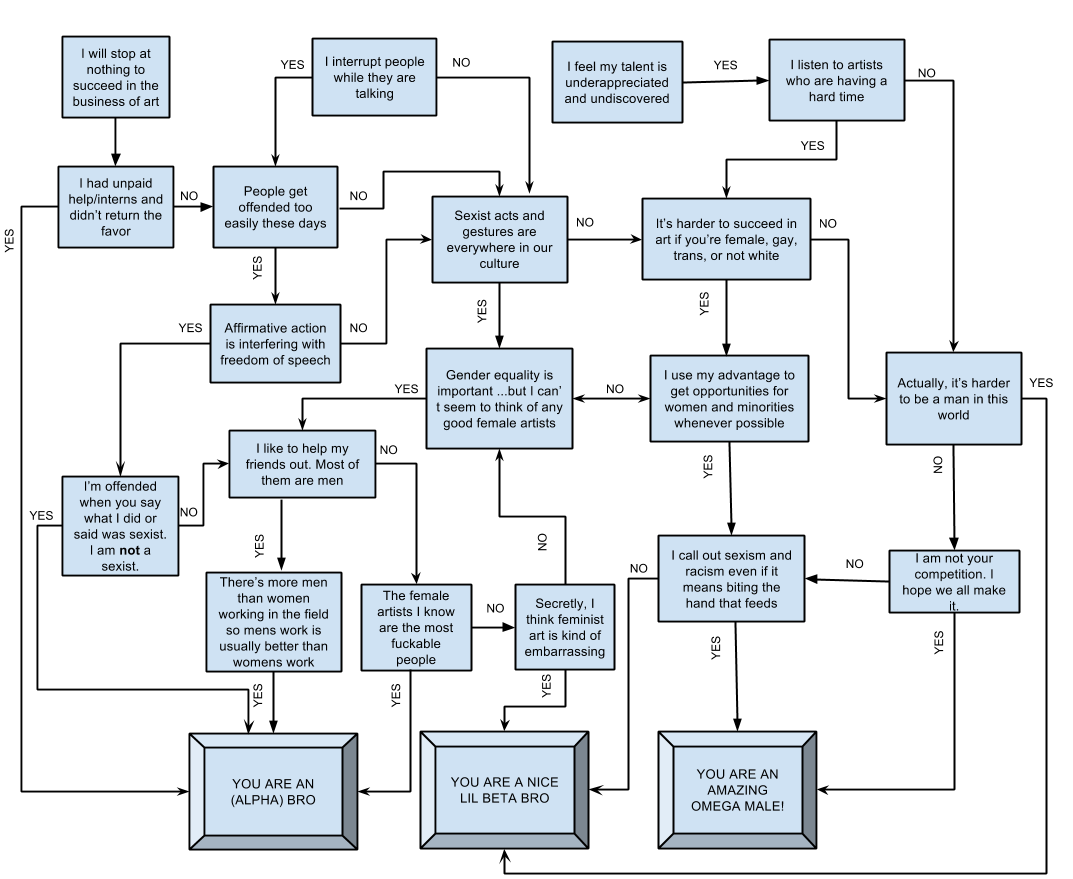

In a 2014 Rhizome interview, Ann Hirsch asked Jennifer Chan—a net artist whose practice touches on masculine tropes like cash, pizza, and bongs—to define the term “art bro.” Chan gave her response in the form of a flowchart quiz that told users whether they were an “Alpha Bro,” a “Nice Lil Beta Bro,” or an “Amazing Omega Male.” She elaborated that the alpha designation, for those who agreed with statements like “I will stop at nothing to succeed in the business of art,” referred to guys who are “shameless” and “sociopathically opportunistic.” This type of young male artist is seriously industrious. He’s got interns. Stefan Simchowitz wants to make him famous. In an Observer article from last September called “Dean Levin and the Rise of the Bro Artists,” Nate Freeman wrote, “The artists set hours, diligently, and can afford apartments in Manhattan.”

We associate this brand of rising art star with an industry sexism problem that is ancient and known. Like most systemic failures, it can be—and has often been—illustrated through the use of statistics. The centerpiece of an ARTnews special issue on “Women in the Art World,” published earlier this year, was a report called “Taking the Measure of Sexism: Facts, Figures, and Fixes.” (Ratio of men to women artists in MoMA’s permanent collection: 5 to 1. Number of advertisements, out of 73, advertising solo shows by women in the September 2014 issue of Artforum: 11. Discrepancy between the most ever paid for a deceased male artist’s work—a Francis Bacon triptych—and a deceased female artist’s work—a Georgia O’Keeffe painting—at auction: about 100 million dollars.) At the time of writing, ArtRank, the (non-parody!) website that provides “data-driven” art investment tips, listed ten male artists in its ten-person “Peaking” category. We all get the picture.

It’s easy to articulate and condemn misogyny when it’s institutional or financial, and much harder when it’s interpersonal, because you run the risk of sounding petty, and probably also scorned. In other words, the Alpha Bro is a much more obvious target than the Beta, who, Chan explains to Hirsch, “may be polite and eloquent but he tip-toes around being a bro; he feels entitled … to the accomplishments of art bros and schmoozes with who [he] perceive[s] to be art power while crying bitter tears of rejection.”

You may resent the Alpha’s status or dislike his work, but there’s no denying that he’s highly productive. But the Beta, despite self-identifying as an artist, forms his connection to art mostly through consumption. He goes to the right openings, reads the right criticism, browses the right websites, wears the right sneakers, but doesn’t show anyone his work. A female artist wrote to me in an email about her experience, five years ago in New York, of “dorky, angry white guys streaming down from Columbia University, immigrating back from their stint at Staedl,” “circle jerking each other to the tune of French theory” and “giggling about 4chan.”

Their handsome heirs, she wrote, “all got nice studios and well-appointed apartments before they had even made a single artwork. … Their scuffed-up Nikes were the new New Balances! This was the birth of the art fuccboi. There was a uniform to put on, a vernacular to pick up. I swear it’s like there’s some underground black-book we women have never seen for how to style oneself into a straight white male artist. I guess it’s called the Internet, lol.” The uniform is specific enough so as to be completely neutral; the vernacular is canned and, frankly, super boring. The problem is that self-styling, here, is self-definition through the expression of taste, aesthetics, and cultural consumption instead of through work, values, and—most importantly from my perspective—interpersonal relationships.

In a recent article for Medium, “Have You Encountered the Softboy?”, Alan Hanson defines the titular character in sentence-long paragraphs: “He has some art to show you” directly precedes “The Softboy does not necessarily have a soft body. In fact he is often wiry and angular.” Much like in the case of my friend’s back-to-back texts about Nikes and commitment, there is no non-sequitur here.

Let me explain. I grew up in a downtown Manhattan neighborhood famous for having been gentrified by artists, went to a private secondary school in Brooklyn that literally called its gym department “Recreational Arts,” and attended an elite university with a prestigious graduate art program. In all of these contexts, moneyed though they were, status was performed through film, art, music, and literary preferences, rather than car, bag, and watch displays. Class maintenance was more creative than material or physical. So I have always been around popular boys who weren’t jocks. Like pretty much every other straight girl in my orbit, I’ve often pined for them and occasionally dated them. When I Instagrammed a screenshot of the Nike Frees conversation, two women commented in quick succession: “I really disagree dude frees are hot” and “Frees are a green light for me.” Our gaze toward these boys is lusty. They’ve had traditional sexual and emotional power over me and over my friends, and yet, I’ve often seen them map their social alienation onto the facts of not being muscular, not liking sports, not wanting to work in finance, and having sometimes been mistaken as gay. I’m not saying that gender norms can’t be anxiety-inducing for straight white boys or men. The thing is, speaking on a general level, I’ve never seen these guys be anything other than affirmed, centered, and rewarded—sexually and otherwise—for embodying their brand of masculinity.

When a (very muscular and very emotionally engaged!) male friend first sent me the Softboy article, I told him it’d be helpful for a piece I was writing about despondent art boys. He wrote back, “They get laid too much.” As my friend, the writer Tracy Jeanne Rosenthal, put it while we were lounging horizontally during a heat wave, “It’s erotic capital that uses cultural capital to hoist itself up.” When I emailed Ann Hirsch, the artist who interviewed Chan, about Beta Bros, she responded, “They’re like the nerds of the art world, right? Who think that just because they are a guy they are entitled to the hottest girl in school? So translated … they think they’re entitled to artistic success, even if they suck, just because they’re a guy.”

Or they feel entitled to both the hottest girl in school and artistic success. It’s not a coincidence that the Softboy, as well as the original and viral “Man-Child” that Moira Weigel and Mal Ahern gifted us in The New Inquiry, are defined both by their literary and aesthetic predilections and by their poor treatment of women. From the first article: “[The Softboy] hasn’t texted you back for a reason; he was not blowing you off. He’s had a Weird Day. Or maybe He’s Trying to Figure Some Shit Out.” From the second: “The Man-Child won’t break up with you, but will simply stop calling. He doesn’t want to seem like an asshole.” As the artist Lisa Jo wrote to me, “Why hide behind crocodile tears and self-pity as a way not to text a girl back? If you’re not that into me, why not just say so?”

It’s a commodification of the avant-garde wherein people’s understanding of themselves as countercultural is rooted not in their beliefs or in how they treat people, but in what they choose to consume. These guys use art as a kind of reflective armor that protects them from having to engage intellectually or intimately in ways that make themselves vulnerable, and also from having to look critically at their own behaviors. But a well-educated straight white guy expressing his interest in Fluxus or Dada or Happenings to assert his difference from and superiority to well-educated straight white guys who like football strips those revolutionary art movements of their politics and, as in all instances of appropriation, renders them tools for the visibility and profit—sexual and social if not financial—of the people who already have our attention. So it’s probably not surprising that these artists often make work that is neither freaky nor prophetic nor beautiful, but derivate, bland, or even non-existent.

It’s not inherently radical or oppositional or punk or even interesting to have good taste. It even seems fair to say that claiming superiority based on taste is good old-fashioned classism. What is revolutionary is a straight man who can be masculine, confident, desired, and still honest, self-aware, and engaged. Besides, it’s cooler to go to therapy than to Documenta.

Emily Rappaport is a Los Angeles-based writer who has lived and worked in New York, New Haven, Portland, and Mexico City. She is reverent of the Sisterhood. Her work has appeared in ARTnews, Flash Art, Terremoto, and Artsy.