Emilie Gossiaux’s “After Image” at False Flag

In 2012, artist Emilie Gossiaux (b. 1989) was involved in a near-fatal bicycle accident that caused her to lose her vision. Formerly a painter, the artist was forced to adapt to new ways of understanding, relating to, and rendering the world around her. In the years following the accident, Gossiaux transitioned to more tactile forms of expression—working predominantly in the realms of sculpture and performance. Now, with her latest series of works, Gossiaux returns to drawing and painting, informed by a keen sculptural sensibility of space, texture, and scale.

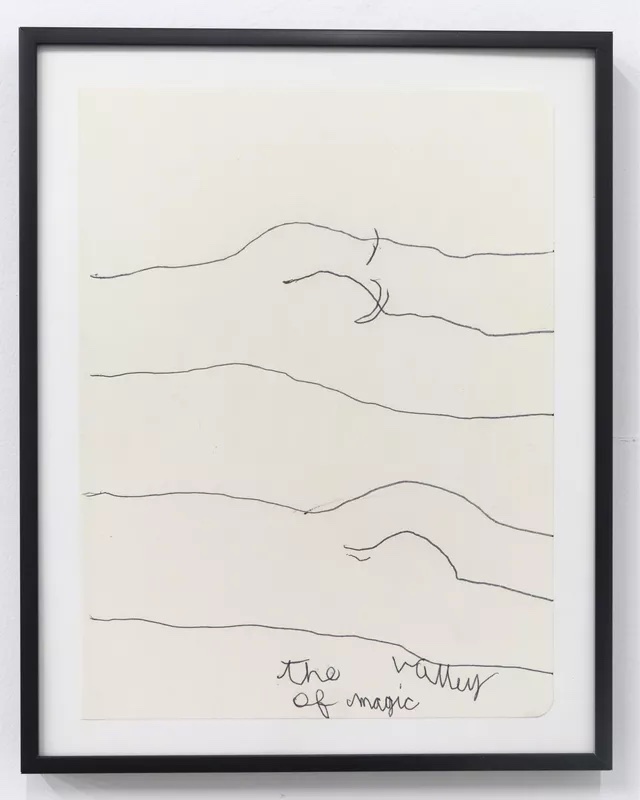

I met with Gossiaux on the occasion of her first solo show, After Image, at the recently repositioned Long Island City gallery False Flag. Sitting beside her in the center of the space, I am struck by the delicacy and depth of the works surrounding us. Oscillating between figuration and abstraction, Gossiaux explores the impressions that linger beyond a visual image, demonstrating a unique sensitivity to touch in both the literal and abstract sense. Narratively, After Image is an ode to the physical body, reveling in the physical and spoken relationships between people. Gossiaux deftly, almost daringly, traverses an array of textures, scales, and materials—ranging from ink on paper to paint on a fitted bedsheet—with a tangible immediacy that is at once light and playful as well as deeply sensual.

Gossiaux’s voice is soft and measured as she describes her practice, her hands gesturing gracefully as she speaks. She explains how in the past year she became increasingly inspired by textiles and has since accrued a sizable collection of fabrics sourced from thrift stores or donated by friends. The paintings in her Bleed-Through series—a series of large-scale paintings on unstretched fabric—were the result of experimentation. She began by pinning a carefully selected fabric to the wall and painting directly onto it, only to find out later that the paint had bled through onto the wall behind. “I could feel the painting so much more on the wall because the remnants of the paint were so much more tactile,” she said. In this way, Gossiaux uses the body as a reference point to understand the physical impressions of memory, dreams, and desire. Emulating the way that our memories and fantasies tend to linger and morph over time, Gossiaux’s works materialize and resonate in a realm beyond the immediate—they are what remains “after image.”

Jillian Billard: Right now we’re sitting in the center of your show, After Image, at False Flag Gallery in Long Island City. I thought we’d begin with your background. Can you talk a bit about your early life, where you’re from, and how you came to art as a form of expression?

Emilie Gossiaux: I’m originally from New Orleans. I think I started drawing when I was about five. I was the shy kid at school, so I was always sitting by myself and drawing in my sketchbook. For high school, I went to this really great specialized art school called NOCCA [the New Orleans Center for Creative Arts]. I went there for two years—my freshman and sophomore years—and then in 2005 Hurricane Katrina hit, so I was relocated to another school in West Palm Beach, Florida.

You mentioned that you are majoring in sculpture for your MFA at Yale. I’m interested to hear how that has informed the works in this show—most of which are paintings and drawings with sculptural aspects. In your first years at Cooper Union, you were focused primarily on painting and drawing, is that correct? Before we get into discussing your most recent works, I was wondering if you could talk a bit about making the transition from painting to sculpture some years back.

I transitioned fully into sculpture when I took a couple of years off after losing my vision. I wanted to work with a more tactile medium, so I began experimenting with ceramics and paper maché. I found that ceramic was a really great material to work with because it’s so free—it can be abstract or representational—and it’s wonderful for working with your hands. The medium is so forgiving, it felt a lot like painting to me.

When I went to Yale, I had to break away from that because they don’t have ceramic facilities. I was comfortable with that though. I felt like I needed to force myself to get out of my comfort zone. So that’s actually been really productive for me. In breaking away from this shell that I’ve created for myself with ceramics, I also wanted to venture back into painting again.

It seems that your understanding of sculpture and ceramics has carried over into these painted works. It’s evident that you have such a keen sensibility of texture, material, and space. Would you say that you’ve become more receptive to material and texture since losing your vision?

Yes, definitely. Feeling things with my hands is the way that I interpret seeing and understanding the world around me. I’ve found alternative ways to develop my work in a more tactile sense using a variety of methods and tools, like stencils and tape and cutouts. Right now I’m experimenting with batik wax again.

Even when I was a painter, though, I never liked painting straight on canvas. I would always do something to alter the canvas, like layer it in wax or something. I never used strictly painterly techniques. For example, sometimes I would create this plastic surface on top of a canvas by layering tons of oil paint to create this super smooth surface, and then I would draw on it with ballpoint pen or nail polish to create this sheen. Sometimes I would layer plaster over styrofoam and paint on top of that surface, almost like a fresco painting. I don’t know what it is—the canvas just felt like it wasn’t enough of an object to me. So I’ve always been really interested in material and texture, even before I lost my vision. It’s just a language that I understand.

Could you talk a bit about your process of making the works for this show? I’m particularly interested in the repetition of figurative imagery. There are the small-scale sketches on paper that are narratively mirrored in the large-scale painted works on fabric. Do most of your works begin as a sketch?

I’ll usually start with a drawing and then I’ll go to a thrift store, or ask my friends to donate some sort of tapestry or cloth. Sometimes the material will give me an idea. Once I touch the cloth, I think about the moment that I want to paint on it. I think about the color, the pattern, and the texture. I come up with an image or a color. I’m always inspired by the material of the fabric. Once I’ve chosen a fabric, I scan a drawing from my sketchbook into my computer and have it enlarged and printed.

I’ve read a bit about this device you would use when you were beginning to get back into drawing after losing your vision—I believe it’s activated through your tongue. Could you explain how this works, and is this still a part of your practice?

The device is called a BrainPort. Basically, there are these tiny little electrodes that shock your tongue. The term they use is “sensory substitution.” So instead of using your vision to see, you’re using your other senses like your sense of touch. It kind of looks like a pair of sunglasses with a camera attached to the bridge of the nose. There’s a wire that’s attached to this tongue piece that sits on your tongue. The camera translates these tiny little pixels in really low resolution onto your tongue, and the tongue piece has these tiny little electrodes that shock your tongue. So it literally draws an image, whatever the camera sees, onto your tongue. If I’m looking at the word “moon,” it would literally feel like you’re tracing the word onto your tongue. You can’t see color with it; you can only see light and shadow. If you imagine that you’re in this completely dark room with all of these tiny lights barely making out a shape, that’s kind of how it communicates. It’s like a low-graphic video game.

I don’t draw with it that much anymore. I used it from 2012–2013. I was part of a trial at the very beginning. That was before I started making art again after my accident. So it was a really important tool for me. I felt like I could be myself and draw again. But since then I’ve come up with new techniques, and have adapted to just using my hands and fingers to draw.

Could you talk a bit about the dreams and memories that inspired After Image?

A lot of them come from desire and eroticism. This whole body of work started with the island and the sunset paintings. Those were inspired by a dream I had about Titanic—but instead of being lost in the Arctic Ocean, it was in a tropical ocean, so I was surrounded by water, and in the distance, I saw a sunset. There was an island beach that I was trying to float toward, and Jack was there. [Laughs.] For some reason, I have these recurring dreams about Titanic—I think because it was such a huge part of understanding romance and trauma and my own desires.

I’m fascinated by the way you’ve materialized Venus (2018), which references Sandro Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus (1486) from your memory. It feels very intimate, as though you’ve traced your personal relationship to the work, and goes deeper than just looking and seeing. These elements of feeling, touch, and embodiment seem integral to your work—not just literally in terms of texture, but also figuratively, in the representation of sensual relationships between people. Is this a recent development?

I think that I’ve become way more inspired by my relationships with people, and by communicating with people around me. That’s become a really huge part of my connection to the world. I get so much information from other people about what they see, and I love talking with people about their ideas. That has been super impactful on my practice. Before I used to sit on the Internet and look at things all the time, you know, and now it’s all about communicating and talking. I think going to galleries and asking people, “hey, can I touch your stuff?” [Laughs.] has been really amazing, too, because it’s allowed me to interact with people more.

This is your first solo exhibition, and it’s also the inaugural show of this gallery space, is that correct? How did you connect with False Flag?

It’s been really great working with Alex [Heffesse] and John [Huddleson]. We’ve known each other for many years now—we met way back in 2012. At that time Alex was working as an architect, and John was into studio fabrication. I was sharing a space with this artist whom Alex and John were working for. We all broke away from that space at the same time and reconnected when Alex and John came up with this idea for running a gallery space. So I knew them when they first opened their gallery in the last location.

Do you plan on working with False Flag again?

I have some work to do for False Flag—they’re going to be in Miami for Art Basel and they’re going to show my work for that. I’m also going to be in Scotland in August for a drawing residency. Until then, I’m just going to be working in the studio.

Jillian Billard is a writer, editor, and poet based in Brooklyn, New York. Her writings on contemporary art have been published by Artspace and Ravelin Magazine.