“Dreamlands” at the Whitney Hums with Conceptual Fiction

Since the release of the iPhone 3GS in 2009, video documentation has become an integral part of the body politic. Cinematic entertainment is not confined to the theater or the living room but rather engulfs the masses in an obsessive-compulsive documentation of “reality.”

The Whitney’s newest and most technically complex group show, Dreamlands: Immersive Cinema and Art, 1905 to 2016, delves into the history of film, and traces its evolution from early experimental cinematic trickery to technological mass consumption. The title of the exhibition is inspired by H.P. Lovecraft’s science-fiction world “The Dreamlands,” which is described as a mirror image of human beings’ waking consciousness. The exhibition creates an immersive environment blending contemporary multichannel installations with Disney studio paper sketches from the 1940s Fantasia. Curator Chrissie Isles brings together a group of some fifty-one artists utilizing modes of installation and technological advancements to construct an extrasensory experience that calls on the viewer to put down their smartphone and be an active participant.

In Anthony McCall’s Line Describing a Cone (1973), a large white semi-circle of projected light is gradually drawn onto a black wall and illuminated by a cloudy mist. The cone-like shape of the light projection cuts through the blackened room, becoming sculptural and disorienting the viewer’s groundings.

On the opposite end of the spectrum, Trisha Baga’s Flatlands (2010) is reminiscent of recent, but not current, stylistic tendencies. Honoring the cut-and-paste, DIY, retrofit culture of the early aughts, participants don 3D paper glasses to view the installation. A dislodged disco ball is placed in front of the screen, projecting little white squares of the film onto the walls and floors of the space, giving us a sense of nostalgia for electroclash art and parties of the past.

Alex Da Corte and Jayson Musson’s collaboration, Easternsports (2014), is another aughts throwback. The Matthew Barney-style installation internalizes hues of bubblegum pink and chartreuse. The four-wall installation creates a comfortable “living room space” with high-design geometric patterned flooring, complete with orange-scented diffusers.

Dreamlands hums with auditory overlays, as the typically white walls of the museum’s fifth-floor exhibition space are transformed into a black box video arcade. The exhibition jumps between varied mediums and formats, from the classic cartoon animation of Mathias Poledna’s Imitation of Life (2013) to Lynn Hershman Leeson’s artificial intelligence bot, DiNA (2004–06). Isles displays an acute knowledge of the evolution of film, and more specifically the complexity of our modern-day interaction with film and technology. Toward the end of the exhibition, the artworks begin to take on new forms of intelligence; as their technical complexity evolves, so too does their subject matter. In these works, the existence of ubiquitous surveillance is paired with the intrinsic impulse to capture, replicate, and consume. The longer one looks, the more the works on display provoke a consideration of the body’s relationship to technology. The question becomes less about entertainment value and the artist’s self-expression and turns toward questions about how you are being watched, and who you are watching.

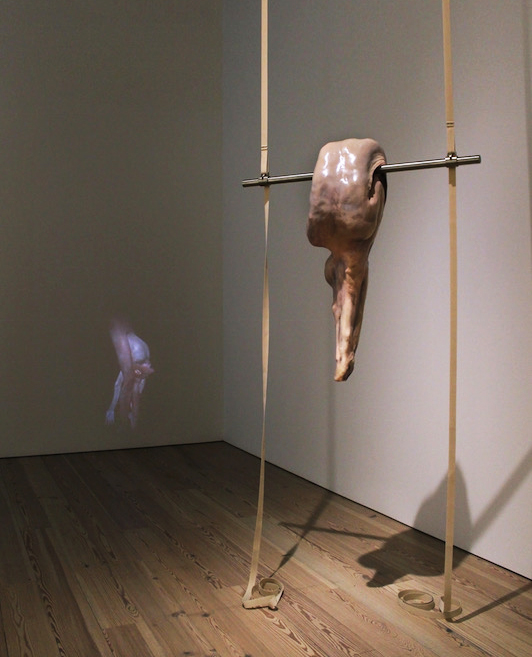

The human form is distilled into a distorted prop in Ivana Bašić’s SOMA (2013), which is presented in two parts. A hand-modeled sculpture of Bašić’s body, which has been manipulated and distorted, is rendered almost indistinguishable. The fleshy form is suspended in the air, its contorted form hanging motionless from two white harness straps attached to the ceiling. The mold’s wax and oil paint composite imply the fragility of the human bod,y as both materials give the form a kind of impermanence. Behind the form, a digital animation of Bašić’s body bends and swivels around itself with disturbingly unnatural flexibility. These distortions suggest a limitlessness, creating a sense for the viewer that, through these manipulations, Bašić’s body becomes nearly immortal. In the same room, Hershman Leeson’s Room of One’s Own (1990–93), which is based on Thomas Edison’s Kinetograph, invites the viewer to peer into a miniature bedroom where a video of a woman plays on a background screen, and a mini TV in a corner of the room displays the viewer’s own eye back to them. In each of these works, the interaction of the body and technology is called into question, examining both our interaction with technology as well as its role in upending the body into a cyborg-like existence.

Hito Stereyl’s Factory of the Sun (2015) veers from the theatrical interventions seen earlier in the exhibition to a further examination of YouTube and self-documentation as a stadium sport. The installation is a motion capture grid, a liminal cyber existence of the twenty-first century. The gallery is transformed into a boundless black gridded space, closely resembling the Star Trek Holodeck. The instinct to absorb the recorded lives of others and the fan fiction of the everyday experience are both at play in this work. Scenes of YouTube stars with their friends, fans, and participants are juxtaposed with narratives of personal experience, mock news, and drones, oscillating between varying modes of reality, a critique of technology that is at once chillingly exploitative and puzzlingly entertaining.

Frances Bodomo’s Afronauts (2014) creates a much-needed moment of reconciliation with the cinematic form. The film is a black-and-white homage to the 1960s ad-hoc Zambian space program and creates a moment of narrative nostalgia that feels unusually foreign in an exhibition that includes works that much predate it. Bodomo’s traditional film speaks to an incessant desire to look back, with a curiosity and longing for what persists despite the increasingly rapid developments of technology in the twenty-first century. This would seem an essential theme of the entire exhibition—the impulse to look back, to record, to document and save, in tandem with the inevitability of progression.

Dreamlands succeeds as a critique of the dialogue which can be had, but often is not, between film and technology. It falls short in providing the historical narrative that its subtitle, “1905 to 2016,” suggests. Instead, much like our modern computation of information, Dreamlands feels at times hectic and convoluted and at other times extremely meditative. Without the more typical graduating timeline, where cinematic and cultural movements are clearly signified, Dreamlands presents a data dump of film happenings; the exhibition gives you all of the information at once. The presentation of film and cinema is however a refreshing departure from the almost numbingly retracted experience of consuming the moving image in the twenty-first century.

Yelena Keller is a New York-based contributing writer for Topical Cream from Oakland, California.