Donetsk Through the Museum, the Monument, and the Diary

In the second feature commissioned by Laura McLean-Ferris as Topical Cream’s 2022 Editor-in-Residence, artist Julia Tcharfas reflects on her former home in Donetsk, Ukraine, through the prisms of the museum and the monument.

Long after we left my childhood apartment in Donetsk, it remained perfectly preserved, like a period room in a Soviet-era museum. My grandmother stayed on for decades as its faithful curator. The apartment had survived my family’s move abroad in 1991, my mother’s redecorating habit, and the Russian military occupation of 2014. Yesterday, however, a neighbor called to say a missile landed in the city center, shattering all the windows on our block, including those of our apartment, and filling my perfectly preserved memory with tiny shards of glass.

Memories are stubborn, persistent. I can still travel to the Donetsk of the past with incredible ease. When I do, I see a duckling wallpaper in a bedroom of unrealistic proportions, an amber-colored playground tucked into a courtyard of towering buildings, a heavenly Pushkin Boulevard with marigolds and sparrows, and a cool red marble fountain in front of my first school. I remember it all in that order, conscious of the fact that this Donetsk exists only as a montage of childhood memory.

In fact, it is the reality of Donetsk today—the separatist region of the Donetsk People’s Republic—that I cannot picture and have a hard time imagining. I thought that Google Street View might provide a window, but the image captures have not been updated since 2011. Everything looks just like it did for decades before the war, before Ukrainian independence even. It is almost as if Street View is colluding with my nostalgia, directing me only to images of the past. The late cultural theorist Svetlana Boym wrote that the nostalgic is unaware that their longing for a different place is actually a yearning for a different time: “The nostalgic desires to obliterate history and turn it into private or collective mythology, to revisit time as space, refusing to surrender to the irreversibility of time that plagues the human condition.”1 To visit my Donetsk is to turn back time in pursuit of a familiar place.

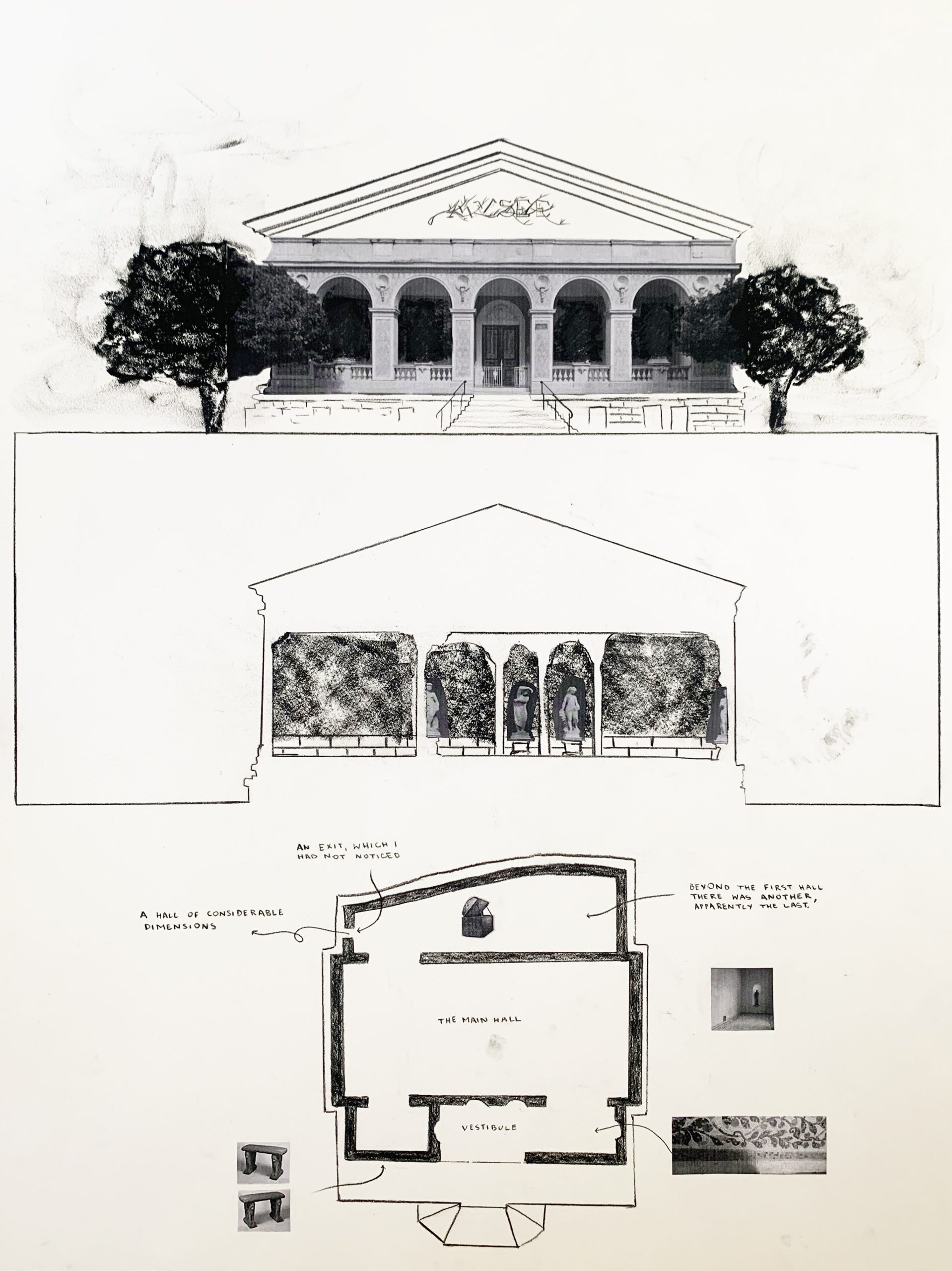

In search of such a spatiotemporal portal, I came across the perils of a nostalgic crossing. I found the irreparable irreversibility at the center of Vladimir Nabokov’s short story, “The Visit to the Museum,” written in 1963 and published in Esquire magazine, with a mysterious heading: “The exile’s lament confuses Time (the beloved past) with Space (the forbidden homeland).”2 In the story, the narrator gets lost in a regional museum somewhere in France, finding himself in a nightmarish maze of infinitely spreading galleries. At first glance, there is nothing unusual about the bits of history on display: the fossils, skulls, an ancient sarcophagus, and prehistoric vases. But the space soon becomes disorienting, chaotic, sprawling. The dummy soldiers, gigantic sculpture, oriental fabrics, a whale, a steam machine, greenhouses filled with hydrangeas, creeks and babbling brooks, laboratories, and yet more unfinished galleries seem to close in around the narrator.

Finally, in a dark room with a coat rack, he finds himself opening a door to a theater, only to emerge outside amidst a “splendidly counterfeit fog.” Looking around, he perceives a familiar scene and immediately realizes, “irrevocably,” where he was transported. Somewhere on the bank of the Neva River in Saint Petersburg—only now it was Leningrad. The museum had delivered him not to the Russia he remembered but to a new Russia beyond his comprehension. In a panic, the narrator begins to shed “all the integument of exile,” the papers and contents of his pockets, including his clothes. Naked in the snow, he is instantly arrested.

In Nabokov’s essay, I see my own attempts to find a way home through the museum. I have burrowed through archives and collections in search of untranslated treasures to stick in the vitrines of my artworks. I clung to jobs that allowed me to speak in Russian: finding parts for the stalled Ferris wheel in Pripyat or translating space biologist tapes. I helped museums mount exhibitions on cosmonauts and Cosmism and bygone biospheres. But I realize that I have stopped short of crossing the portal. I fear that what awaits me on the other side is not only some new horrific version of Donetsk, but with it, a certain loss of identity. In his opposition to the totalitarian Soviet rule, Nabokov gave up all ties to his homeland, including writing in Russian.

My family left the Soviet Union when I was nine. We spent three years in Poland and ultimately landed in Los Angeles in 1994. Shortly after all that, my father returned to live and work in Kyiv. My mother followed him in 2009. I got to live in Donetsk again for a few months when I visited my grandmother shortly after the loss of my grandfather in 2008, staying in the apartment of my childhood, everything in its place—even the ducklings on the wallpaper.

A young guy came to install the internet in the apartment when I arrived. Our brief conversation has been replaying in my mind these days. We spoke about how things changed and didn’t change, and he talked a lot about loss. He felt that when Ukraine broke from the Soviet Union, some history got lost in the transaction. Seemingly overnight, Ukraine began to erect new museums, stage new programs, build new monuments, enforce a new primary language. Ukraine, which had little political sovereignty for most of its history, always divided between empires, was resurrecting its centuries-old culture. The internet installer’s personal memories became splintered by two national mythologies.

I worry that as an émigré, I too got stuck in a historical anomaly like the internet installer. I worry that in my head I return to the wrong place. That people my age in Ukraine have a fading memory of the Soviet Union, while for me it is my only memory of home. I worry I missed my chance to learn Ukrainian, and therefore my chance to think or dream in Ukrainian. I worry I am missing time. I worry I am trapped in the museum.

***

In Donetsk, time ran slower than in the rest of Ukraine. People there were not quick to take down old monuments or erect new ones. The streets were filled with aggrieved ghosts of another era. On the dangers of nostalgia, Boym warned, “In extreme cases, it can create a phantom homeland, for the sake of which one is ready to die or kill.”3 In 2014, pro-Russian protests began to haunt Eastern Ukraine. Armed and occupied by the military, they set in motion a historical reenactment with deadly consequences. Eight years into the war, Donetsk’s corroded memory was used as a vile pretense for a gruesome full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Here in the anxious present, I find my memories of Donetsk no longer serve me to understand what is going on at the other end of the portal. To make sense of the madness, I turn to cinema, to literature, and to the young artists that live in Ukraine.

Sergei Loznitsa’s 2018 film Donbass (named after the joint territory of the two separatist People’s Republics of Donetsk and Luhansk) provided a surreal glimpse into the everyday violence of Eastern Ukraine under the Russian occupation. Loznitsa is well known for his immersive, unnarrated archival documentaries exploring Soviet and post-Soviet history that wash over the screen like disembodied memories. In Donbass, however, Loznitsa can only enter the occupied territories through fiction and short stories belonging to propagandists, petty corrupt officials, predatory gangster police, unmarked soldiers, people living in underground bunkers, and other dead souls. The grim reality on the ground is stitched together with snippets of life full of confusion, national myth, and distorted lies.

The attempt to capture Donbass in both its realism and its folly is echoed in Yevgenia Belorusets’s recently translated collection of short stories, Lucky Breaks (2022). Belorusets has an abiding concern for the lives and stories of Eastern Ukrainians. Many of her short stories are set in Donbass or feature the region’s refugees in Ukraine. The stories begin after the 2014 occupation and are littered with a sense of historical confusion, misremembered time, and rewritten plots. Her characters are manicurists, amateur astrologists, a florist from Donetsk who joins some group of partisans and whose shop is retrofitted to store propaganda, a barista who names coffees after her dreams, a woman who moves into the memory of a recently refurbished apartment after it is destroyed.

In a short story called “March 8: The Woman Who Could Not Walk,” one of Belorusets’s characters gets stuck on a grey granite bench, gradually fusing with it. She finds herself on what used to be the Square of the October Revolution and is now the Maidan Independence Square, as a body and memory turning to granite: “I am a living monument … a monument that is soft, unstable, and wobbly …”4 Fixed in place, the human monument seems unsure of her message. People hardly notice, mourn, remember, or celebrate her fate. A passerby casually tosses a bouquet of flowers at her feet. Daily life, historical events, and the afternoon breeze come and go.

Belorusets is now writing a day-by-day war diary from Kyiv on the pages of Artforum and ISOLARII. In a coincidentally matching dated entry, “DAY 13 (TUESDAY, MARCH 8): “THE NIGHT IS STILL YOUNG”,” she describes the emptied and fortified Kyiv surrounded by war as “a city without a present, with only a past and a future.”5 She is joined by dozens of artists, art historians, and curators all over Ukraine publishing daily wartime diary entries of eyewitness accounts and lived memories. Unlike the mythology of the monument, the diary gives voice, agency, plurality, immediacy to the Ukrainian artists and their experiences. “We are still here,” they echo. They are reclaiming their history: “soft, unstable, and wobbly.”

Julia Tcharfas (born 1982, Donetsk, Ukraine) is an artist based in Los Angeles. Her research draws on materials from modern scientific and technological folklore and takes the form of archives and exhibitions. Tcharfas is the founder of Before Present project space in Pasadena and has exhibited work in Magic Hour, Twentynine Palms; the Swiss Institute, New York; Project 1049, Gstaad; and Transformation Marathon, Serpentine Gallery, London. A profile about her practice has been featured in the Swiss Institute’s SI: Visions video series.

NOTES

1. Svetlana Boym, The Future of Nostalgia (Basic Books, New York, 2001), 19.

2. Vladimir Nabokov, “The Visit to the Museum,” Esquire, March 1, 1963, 111.

3. Boym, xvi.

4. Yevgenia Belorusets, “March 8: The Woman Who Could Not Walk,” in Lucky Breaks (New Directions, 2022), 19.

5. Yevgenia Belorusets, “Letters from Kyiv: A wartime diary by Yevgenia Belorusets,” Artforum, March 8, 2022,

https://www.artforum.com/slant/a-wartime-diary-by-yevgenia-belorusets-88035.