Do You Know the Works of Sara Hornbacher?

If I focus on the thought, the memory quickly sharpens: the first time Sara Hornbacher materialized. Her tall frame was a dark imprint against an empty sky. I didn’t know then that this was a uniform, not just an off-the-cuff style option. The look was a constant for her, and functioned as a direct signifier of her interest in all things structural, architectural, systematic. She was there, quickly walking, gliding in-between concrete and aluminum in an institutional breezeway.

Hornbacher was the chair of the video department at Atlanta College of Art, her long legs in tight black nihilist leggings, with a long black t-shirt to cover bottom extremities. The look came with the permanent accessory of a black “Joan of Arc” cropped hairstyle and deep red maroon lipstick, always the same Pantone shade, the only baroque element of her uniform.

The breezeway was an architectural addition that connected the art school to the High Museum. ACA was a type of Black Mountain College, if you will. A school based in the Bible Belt that was very serious about conceptual art. The school has now been sold to and shut down by Savannah College of Art, who didn’t want to compete with a conceptual art school in their new real estate conquest of Atlanta. But, before this, Hornbacher was one of these conceptualist do-gooders, time philanthropists, tastemakers, and more importantly, taste shapers. Not only did she have style, she was good at her job. She was a sought-after educator; where else could a student go to learn about 1970s endurance films? And like those films, her stamina as an artist defies logic, with an overture that spans decades, from 1974 until now.

Hornbacher’s career began in 1974 when she chanced upon the exhibition The Projected Images at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis. The exhibition featured such canonical figures of experimental film and video as Paul Sharits, Michael Snow, and Peter Campus. It was a life-altering experience for Hornbacher, and Sharits encouraged her to come to Buffalo. At the time, Buffalo was the epicenter of Structuralist film and Sharits was teaching there at The Center for Media Studies, alongside pioneering video artists Steina and Woody Vasulka. Not only were Sharits and the Vasulkas teaching in Buffalo at this time, but CMS founder Gerald O’Grady had recruited many other artists whose work would be extremely influential in the years to come, including Hollis Frampton and Tony Conrad.

Hornbacher was initially only one of two women who enrolled in the program in 1975. CMS was an extremely male-dominated department, unlike the painting and photography departments down the road at Buffalo State University (where Cindy Sherman and Robert Longo were graduating that same year). This was partly because the pioneers of the medium were predominantly male, but also because experimental film and video were considered technical, graphic, and computer-based art forms.

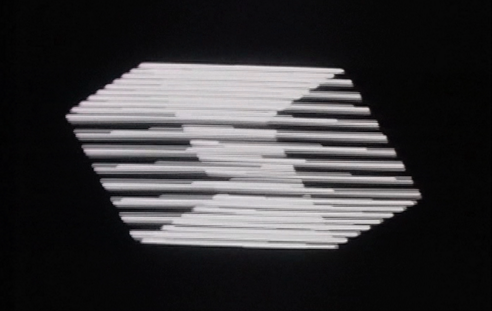

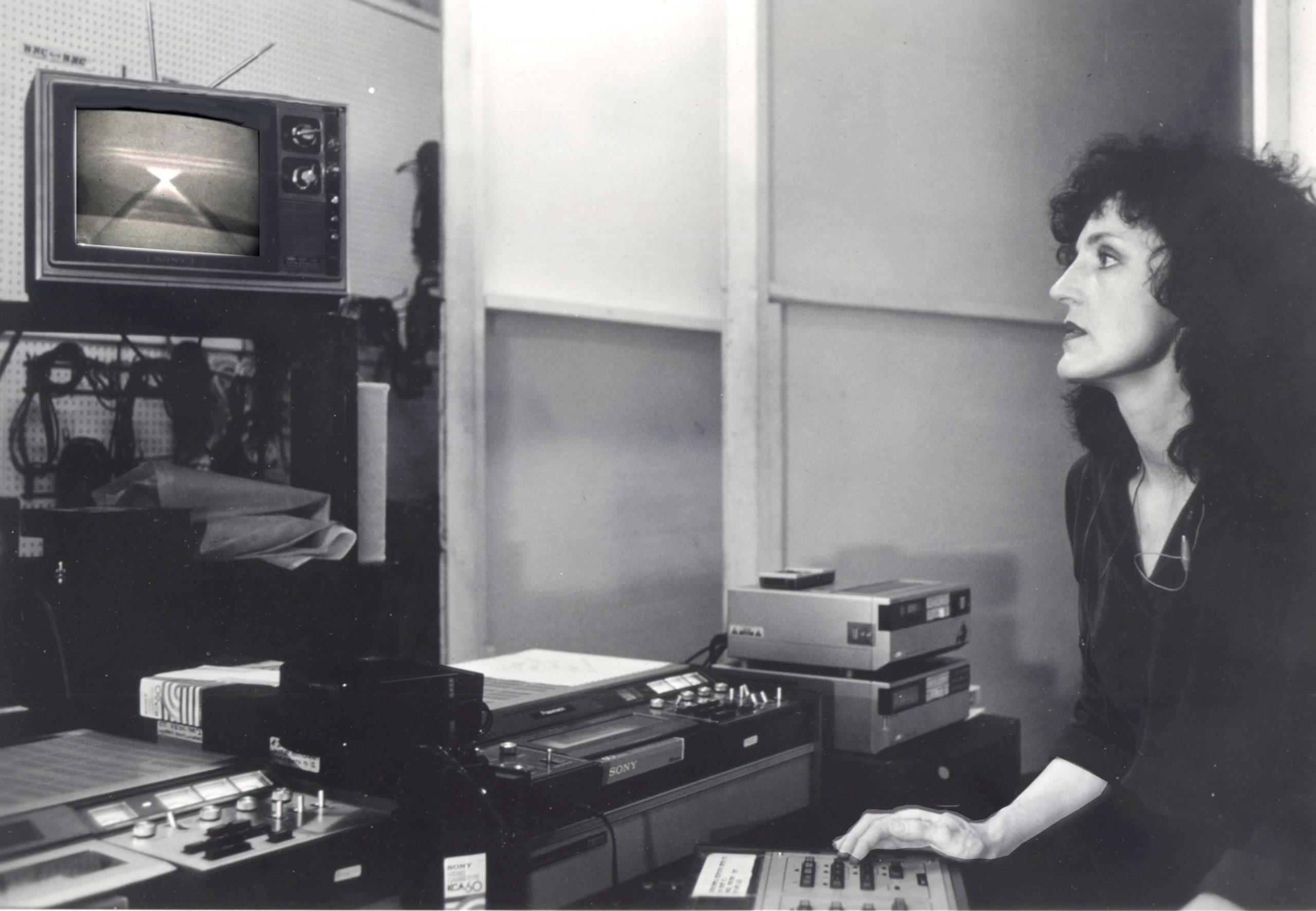

Still, the possibilities were boundless and exciting. While still enrolled at CMS in 1976, Hornbacher completed her first residency at the Experimental Television Center (ETC) in Owego, New York. ETC not only provided space for video artists to work, but the institution also developed much-needed hardware and software as the limits of the media were pushed. ETC was a key foundation in the history of video art, and provided a technical, social, and creative base for the artist to work. Hornbacher was one of the leading artists to take a technical as well as creative approach to the medium. Her work reconfigured electronic abstraction and questioned what an “electronic image” could be.

In 1980, Hornbacher spent an entire year immersed in making her own work at ETC and then moved to New York City in 1981. Hornbacher was a first-generation artist using electronic image processing as an emerging medium. Shortly after settling into her new life in the city, Hornbacher was included in the exhibition Video: Abstraction and Image Processing at Anthology Film Archives and Themes in Image-Processing II at The Kitchen. Around this time, in addition to her practice, she was working in the television industry and helping to shape the landscape of video art. She was the guest editor for the first CAA Art Journal issue on Video (1985) and curated two compilations of experimental work showcasing her peers’ work, each several hours long, for Art Music, The Kitchen, and The American Film Institute. Her first solo exhibition in New York, Engendered Species, was mounted at New Math Gallery in the East Village in 1985.

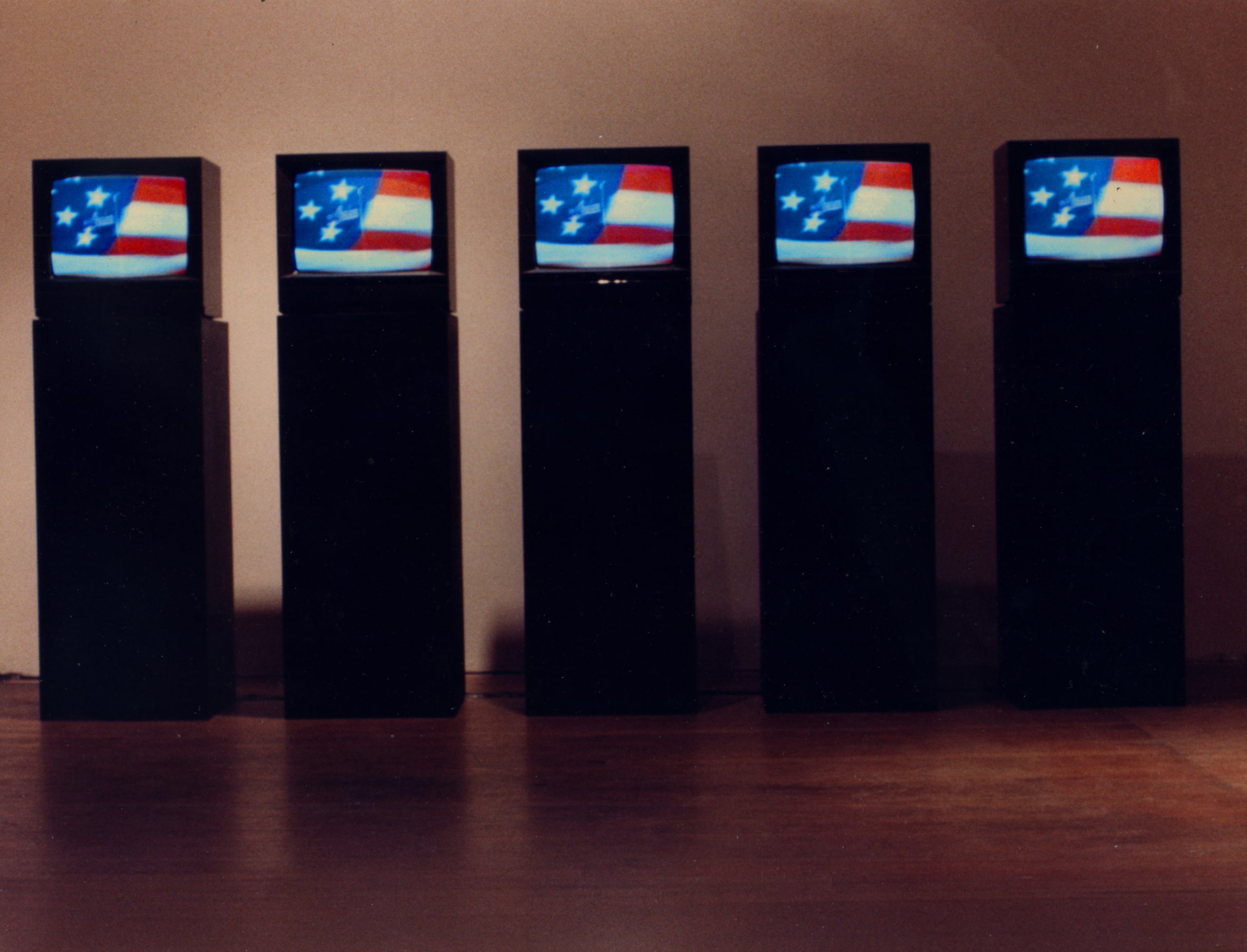

In 1986, interest in Hornbacher’s work grew. Quickly after, she executed an “electronic environment,” as she called it, for PostMasters Gallery. In 1989, she was included in the Whitney Museum exhibition Image World: Art and Media Culture. The survey was the first of its kind in many ways and prioritized artists who were critiquing mass media in their practice.

Hornbacher cemented her reputation as a pioneer of video art herself, separate from her teachers like the Vasulkas at CMS, when she represented The United States at The Fourth Annual Australian Video Festival in Sydney, Australia, which produced a monograph titled Scan + A. The conference that year was focused on Marshall McLuhan, whose work greatly inspired Hornbacher.

Hornbacher’s tenure in New York City lasted from 1981 to 1994, after which she moved to Atlanta to chair the video department of Atlanta College of Art. Her son Scott Hornbacher stayed behind in New York and held onto the family apartment in Tribeca and worked in film. He went on to executive produce the New York-based series The Sopranos, until finally settling in Los Angeles where he became the executive producer of Mad Men, and directed nine episodes.

Since 1974, Hornbacher has continued to explore and expand the parameters of site-specific installations, using aspects of electronic imaging. She’s also taught many generations of video and visual art students, including myself. Her single-channel videotapes, lenticulars, and sculptural works have had an impact on many generations of filmmakers and contemporary artists.

Lyndsy Welgos is the founder and director of Topical Cream 501c3.