Digi-Feminism

Filmmaker Yasmin Geurts talks about the moniker “Digi-Feminism” and her project of interviewing female artists from around the internet who are using their image as a tool of rebellion.

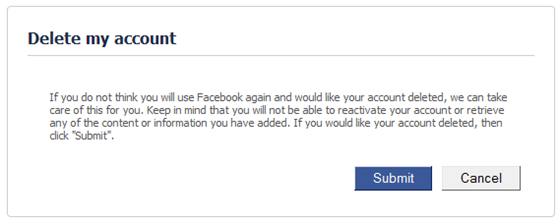

Like a contemporary Ophelia, I began this past year in an apathetic haze, drifting through an illness that left me bedridden and surrounded by flowers. With paralyzing chronic pain, I was unable to create; there weren’t many options for entertainment. Luckily Gilmore Girls had been added to my Netflix queue to keep me semi-entertained. After a month crawled by, I developed major depression. For weeks I compulsively scrolled through various social media platforms, triggering some obsessive neurosis I usually keep in the back of my closet. Through my thumb’s manic affair with my iPhone, I happened on a growing corner of the art world. Like a burgeoning multicellular organism, artists like May Waver, Nancy Leticia, Signe Pierce, Sadaf H Nava, Claudia Maté, Bunny Rodgers, Alexandra Marzella, Junglepussy, Leah Schrager, Anne Hirsch, Erin Grant, and Juliana Huxtable tumbled into my news feed. As an artist frustratingly hesitant to delve into facing my own identity, this inspired a curiosity for more; I found a moniker coined “Digi-feminism”, a millennial-fueled transmigration towards the fifth wave. Stemming from Net Art, the community uses an assortment of digital mediums such as video, poetry, and photography, usually adopting the selfie as one of the tools for reclaiming the female image. The artists take a break from traditional methods by sourcing an actualized transmission of the self, allowing the analysis of existential themes. Not to mention, there is also a myriad of pseudonymous artists who possess the ability to escape counteractive exposure or harassment through binary resurrection. By simply clicking “OK” after “Are you sure you would like to delete your account?” an artist can potentially be reborn.

Body Anxiety is an online exhibition curated by Leah Schrager and Jennifer Chan. The exhibition changes the way we publicize artwork by utilizing a symbiosis with tech. The two put together a group of twenty-one artists who predominantly use their own image, or an adaptation of it, within their approach. The artists in Body Anxiety broadcast and manipulate their own form, defining the substantiality of their artwork, and creating the conceptual impact that every piece has been free from the influence of a man’s hands. The artists channel intuition and cultivate their self-expression, despite the underlying concerns of becoming dehumanized at the whims of the internet’s overwhelming problem with sexism.

Individuals who suffer from discrimination still struggle with the unease of being scrutinized for displaying the intimacies of their work publicly. It’s something web culture doesn’t frequently talk about, but many of us go under fictitious identities to explore anonymity. My favorite reference is the avatar, functioning elusively with semi-organic features mirrored by program-generated enhancements. Claudia Maté is an experimental digital artist and adept web developer living in London. Maté is a prime example of someone advancing the avatar, or cyborg in her artwork. She recently had one of her creatures installed for the Björk exhibition at MoMA.

When Leah Schrager and I arranged a time to speak, it ended up being an early Thursday morning. Dancing around time differences, I snuck away from an intensive meditation retreat in Santa Cruz. Feeling predictably introspective, and sleep-deprived as a result of a sawdust-filled mattress, I perceived my own youthful social awkwardness. In addition to being the co-curator of Body Anxiety, Schrager is a full-time graduate student and works a day job as the Naked Therapist. When I reached her she had just finished grocery shopping in NY, which, depending on the floor you live on, can be just as exhilarating as being at an Equinox Tae Bo class wearing ten-pound ankle weights. Both a little worn and semi-unprepared, we started the conversation off with Leah’s inquisition about my own work—she attempted to search for a website but couldn’t find any evidence of my existence. She then asked if my name was under a different alias. I opened up and admitted that I’ve been changing my heading frequently. Trying to remain free from family judgment and the eyes of an online stalker, no identity has really stuck yet. She became inspired to lift off into our brief conversation from there.

“When dealing with women and their images, one can so easily move from commercial to art, or to pornography from art. I personally just started sharing my work under my real name in 2014. It was a long process of negotiating and dealing with questions of online trust, including some personal anxiety. Many female artists I know use an alternate identity; it’s a common theme that comes up within this community.”

Leah Schrager

Feminism is a nonlinear journey, burrowing into hibernation after each wave to emerge famished and inspired. Pragmatically, as an innovative group of individuals, these artists utilize new technologies to refine their approach. Feminist net artists are reclaiming their image so that eventually, their voices will be heard without judgment based on sex or identity. Erin Grant, an NYU graduate, filmmaker, and performance artist, has a realist view on the social structure of modern-day feminism. She observes counterintuitive influences mainstream media has depicted about current feminist archetypes, and rejects them by letting her body speak through her cinematography and performance art.

While viewing Erin’s piece, titled I Lose Myself Because I Can, I was filled with a bare nostalgia I’ve experienced facing my own femininity against the strength of an ocean tide. Nothing feels more human than letting your body and mind get swept away by the source of all creation—on the edge of land and water, half in control of your own form but still being pushed and carried by natural forces. There was an inherent dynamic through the artist’s vulnerability as the gentle yet aggressive waves methodically pushed against her. While there were moments of defenselessness, struggling to keep her head above tide, there were nonlinear glimpses of enlightenment while the artist offered herself to creation. The movement seemed to generate a sense of blessing through the act of surrendering one’s body to its own innate desire for expression. This was reminiscent of uploading artwork online and letting the media currents carry it away. The piece remains tethered to the creators, thrashing against granules of perceptions. The incorporeal idea becoming its own identity, crawling out of the internet, molded into its own unique cultivated evolution.

“Women are told in many different—both literal and contextual, and often I think subconscious—ways that their selves are not valuable and that their selves don’t have inherent worth. Even before female artists are to make anything, we are inundated with messages that tell us that our bodies and our thoughts and our feelings and our ideas and our words—are not worth as much—are not worth anything. In that sense, I think for a woman to make work about finding worth in herself is rebellion. When a woman’s work is invalidated because it includes her body, I mean that’s violence to the self. I think everyone wants to be seen, I think everyone wants to be recognized, and I think everyone wants to be validated. I think that is a human impulse. I don’t know what there is to do besides to keep using my body on my own terms. And I’m trying as hard as I can not to be afraid that it will be dismissed and I hope that I never reach a day where I stop fighting—for myself.”

Erin Grant