Decolonizing Time as Healing

Time has never felt like the truth. Not here, not in the U.S., where we still spring forward, fall back. Not in my high school U.S. history class, where the bad isms were deemed a thing of the past, not a bedmate to the ills of the present. In the American South, slave owners were once fascinated with clocks, buying pocket watches by the dozen; laborers and slaves were forbidden to own watches themselves, and the master clock was literal. The legal dissolution of slavery was dubious, and enabled it to continue in various incarnations; the broad internalization of colonized perceptions of time was permanent.

Some folks say that history stays in your blood—that our genes carry memory, that the womb is a carrier for past anxiety and joy, and that a grandmother’s trauma might’ve colored the shades of your mood. Others say the idea that history can poison you is troubling at best, mostly racist, and wholly inaccurate in any case—true, but even if I don’t hold my family’s pain, I still think, hope, pray they are with me, somewhere in my veins. These days, every calendar starts with an origin story: in the Christian year 2000, it was 1420 in the Muslim calendar, 2543 in the Buddhist calendar, 5760 in the Jewish calendar. Your god plus sunset equals time.

My understanding of time as a colonial construct, maybe obstruction, has ascended in tandem with a desire to know the past, to know my ancestors whose history begins somewhere aquatic, before we had legs. I’ve paid more attention, too, to the art that deconstructs and disavows Eurocentric time and suggests some other perception. To the artists—mostly women—whose work invites a timeless idea: the past stays with you, and the past is future, and the present is already past. If we can shift one, we can listen to another.

In September, at Basilica SoundScape in Hudson, New York, I wandered into one of the venue’s rookish alcoves, an empty room where a video by Tabita Rezaire was screening, projected cold and small onto the stone. It was noisy out there (maybe Lightning Bolt was performing, at that point in the night). I couldn’t hear a thing, but I could read Rezaire’s words: “Honor your womb with divine orgasms. Honor your womb with dance.” Rezaire makes dream-like videos, moving collages. Here, her heart becomes a uterus, her dances become a trance. Images recalling ancient history are rendered spinning and pink: a blinking pyramid shines like a Blingee. She twerks, masturbates over layers of flouncy filigrees, meditates. She invites you to do it, too: Heal your womb, heal your future. She is the High Priestess of the Rider-Waite tarot deck, layered and inviting, wise, clitoral (see the High Priestess’s hat). Rezaire is the Goddess archetype, or maybe the Maiden. Margaret Carrigan at Hyperallergic writes: “Rezaire’s digital photo collages of herself as the archetypal maiden … offer a timeless vision of the divine feminine. And by timeless I don’t mean classic, but literally without a fixed time.”

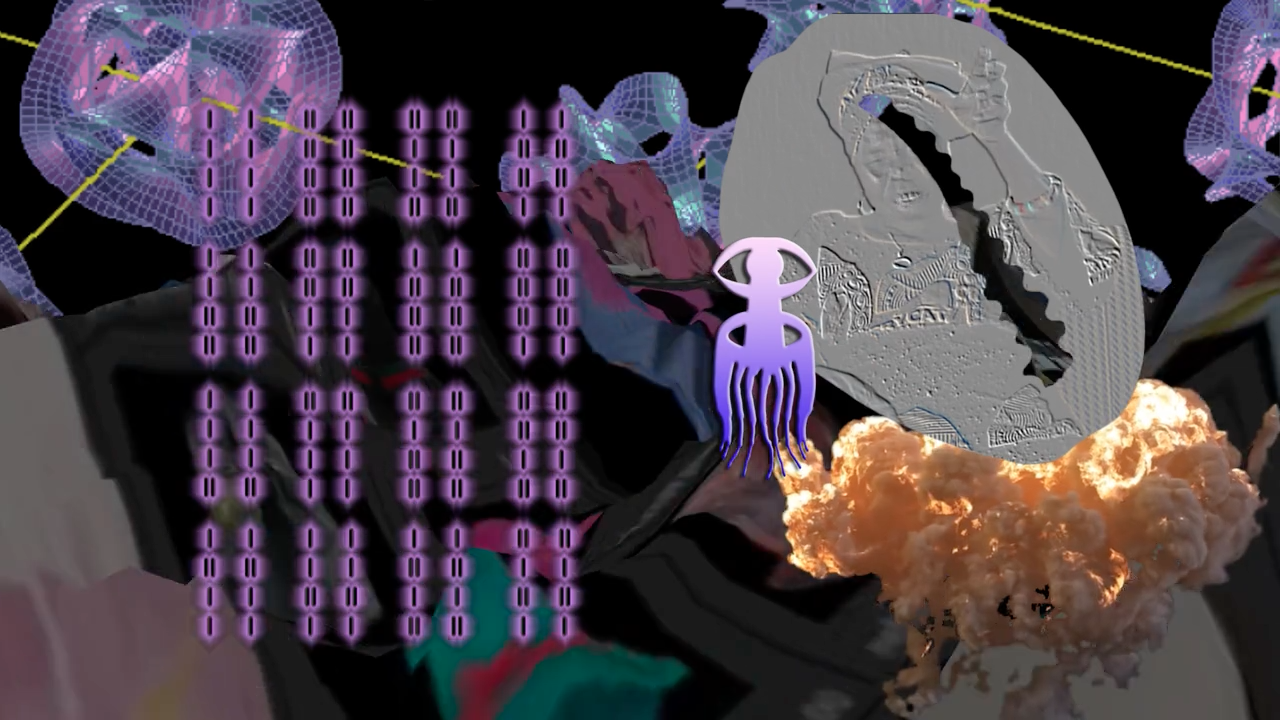

Rezaire has a healing practice; if it’s separate from her artwork, the two filter through each other. Her public performances often incorporate healing circles—she’s a certified yoga instructor—and videos like Peaceful Warrior (2016) offer instruction on how to live in a “world where we are not affected, ssssscared, hurt … Where we do not care about white supremacy, homophobia, transphobia, fat-phobia, misogyny, patriarchy, ableism, ageism.” She hisses her esses, like a snake; step one in becoming a peaceful warrior is engaging in decolonial self-care. A digital snake appears, many-headed and slithering. Purple text: ANCIENT FUTURE. “We shall invoke the power of the sssserpent, and connect with our ancestral knowledge.” A zap. She moves from an etheric portal realm to a world of hieroglyphics.

In an interview with Rhizome, Rezaire explains, “Our soul bodies contain the whole of the universe, the whole of space-time. We are literally made of space-time.” The record of stardust is a tab in our DNA—a reference point to the cosmos. If we can tap into that, Rezaire implies, we can meet our ancestors, travel backward or forward in time.

My friend Jamilah Sabur is an artist, and she spends lots of time toiling on the internet, reading about the peripheries and triangulations of every subject she’s become entrenched in. She told me about the Aymara, for whom the future lies behind, the past ahead. The future is at their back. Elysia Crampton, the musician, producer, and poet, is Aymara; she dedicated her self-titled album, released in 2018, to Ofelia—who, she says in an interview with TANK Magazine, “was one of the mariposas, or butterflies, who forever altered the costume China Supay in the 1960s and 1970s, the Aymara femme devil performed by queer and trans bodies in the street festivities, which, though now formally Christianized, can be traced back to before the conquest.” Ofelia and her friend removed the mask once worn with the costume, unhidden.

I asked Crampton about time and the Aymara over email. “We’re often told those that live in the past are sick, insane, or addicts living outside of reality,” she wrote me. “But physics and neuroscience even teach that what is experienced as the present or ‘being in the here and now’ is really the past—there is a lag between sensory perception and interaction. Perhaps that lag is part of a more fundamental cut or fracturing that opens up to grace or providence.”

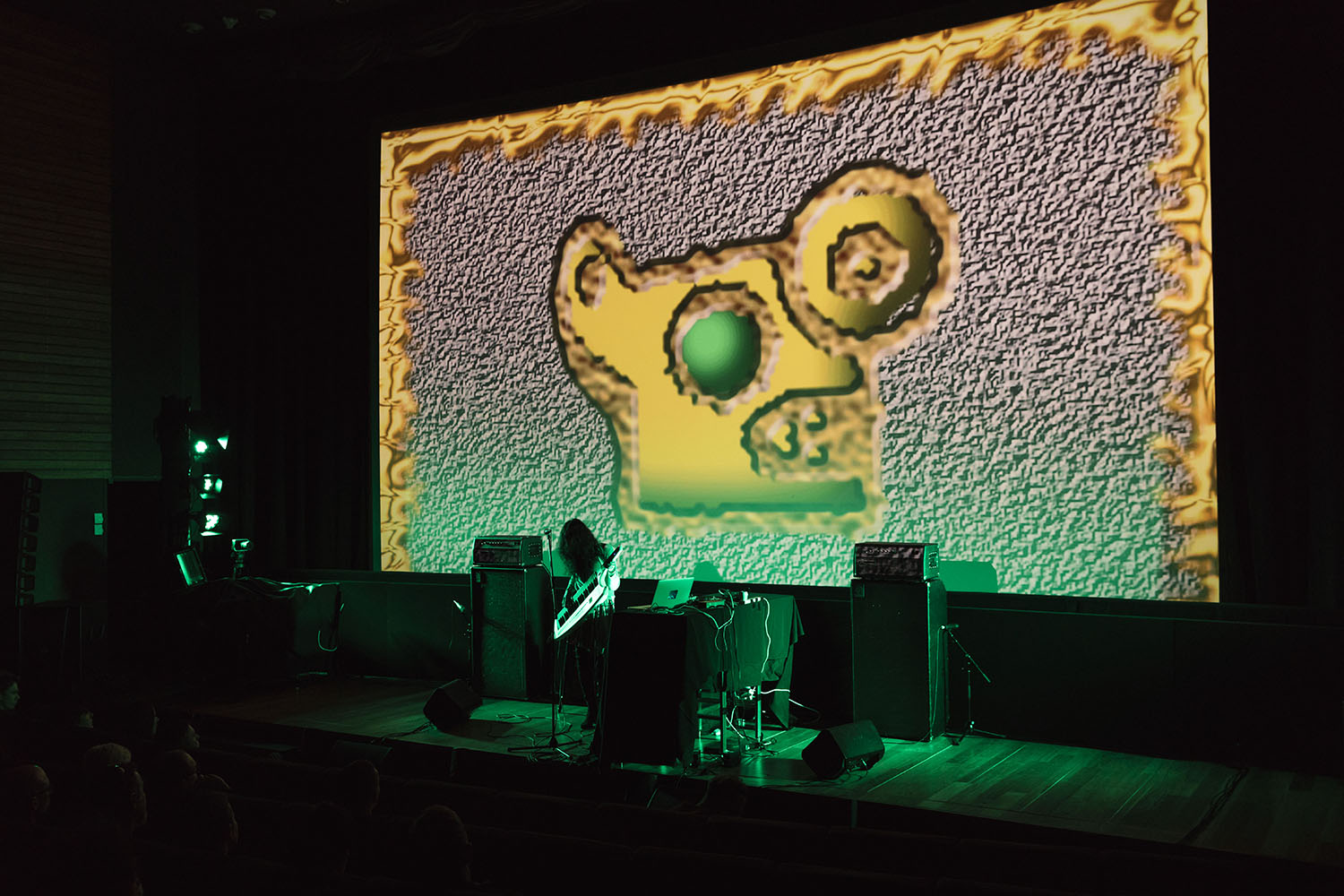

I’d long thought my body was its own, but maybe a sort of carrier, and that its presence was present. That what I felt now was now. Crampton is in the business of cosmic unearthing. She uproots unviolently—turning over a rock to see its other side, the layers it contains. Her music sounds like everything distilled. One song from American Drift is all glottic, clicking gun noises, keys so high they sing like flutes or cardinals, strings that feel impending. Something like Shannon’s “Let the Music Play,” but over and over. Reverberated voices, elongated and tinny. A rumbling cyclical, like kantu rhythms, and cosmic, like stars’ explosions, which have occurred in a time-space so removed from our own they still look intact to our gaze. The song enfolds you. Perfect, it’s called “Wing.”

I asked her about uncovering the history in her own body. “Is there such a thing as ‘my own body?’” she replied. “What I love about biology and physics studies is that, like our daily spiritual walk, they tug at our fabric—fracturing the animal and history’s self, el caporal, the overseer, self-governance as a mark of existence or sanity. We feel the vacuum that composes us and that we hold, respiratory chamber braided with ecology, nothingness that isn’t nothingness, our nothingness haunting ‘itselfness.’”

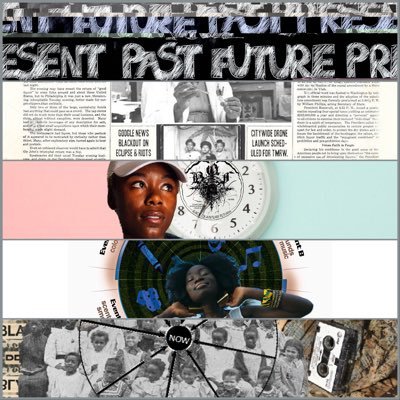

The collective Black Quantum Futurism tug, too, at the fabric, though the one they stretch is the velvet of space. A database of their projects looks like a map; at its center, there’s the shape of electrons around a nucleus. Moor Mother (Camae Ayewa, a designer, photographer, and musician) and her partner Rasheedah Phillips (a writer, lawyer, and advocate) started the duo, they explain in a statement, as “a new approach to living and experiencing reality by way of the manipulation of space-time in order to see possible futures … This vision and practice derives its facets, tenets, and qualities from quantum physics and Black/African cultural traditions of consciousness, time, and space.” They are artists and activists both: in 2016, they created the Community Futures Lab in North Philadelphia, a rapidly-gentrifying area, to offer housing resource workshops and zine-making classes. A year later, at Project: Time Capsule, a performative reading, songs and poems became mythic rituals about time, space, and the freedom from both.

On a linear, Eurocentric, white-centric timeline, Black Quantum Futurism have purported, black history is made to look thin, minor—a movement here, a protest there. Truth is, every movement was born long ago, and their impacts stretch into the future, like echoes. That’s healing: remembering the dense, limitless truth of a people. Moor Mother’s “Time Travel Meditation on Ritual” asks:

How do we prepare to die, prepare to leave?

How do we participate in our own beginning?

When do we collect our past things?

Those things lingering around in our minds

[…]

Which way is home?

How do I get to the beginning?

Only my memory remembers the past

[…]

Can’t use they clock

Never seems to be working

Always 2 minutes past

or a quarter till

These minutes and seconds

disappear and reappear with each step who is collecting

on this invisible currency?

On their website, a song accompanies the meditation. Its rhythm and samples move in a circle. Quantum physics complicates linearity and “communities.” Phillips has written, “The linear time scale was developed alongside institutions of imperialism, colonialism, oppression, slavery.” Nothing more scientific or biological, really, than knowing the truth of your history.

The atemporality of this particular phase in my life—in our collective life, maybe?—has become a kind of memeable joke: “2018 already almost over,” read one, at the end of January 2018; when this year’s January ended, another meme said, “January was a tough year, but we made it.” I thought it was the way adulthood had settled over my life like a heavy blanket, stripping the day of its nuance. Then, my father, who teaches college freshmen, told me that for the past year, his students—who were usually bored by the passage of time, how it dragged—felt it was passing too quickly. “Friday already?” they’d say, when years before, it couldn’t come soon enough.

This feels new to me, this time compression. But it isn’t, really. Every time I’ve thrown some sort of tantrum, felt my anger—at the world, at myself—rising in my temples, my mother says to me, “That’s that Cora gene,” referring to a Spanish colonizer from whom we are allegedly, distantly descended. Hardly anybody on her own mother’s side looks Spanish; they are mostly Afro-Caribbean. It’s not Cora stoking my anger, is it? It’s his cruelty. I’ve Googled him, but can’t find a thing. I’d have to talk to him myself, in dreams. In the previously mentioned Rhizome interview, Rezaire explained: “I believe healing starts with being in conversation with darkness, as in what is not exposed, outside of our knowing. Facing our fears, going where it hurts, revealing the words … Healing is birthing a different state of being and birthing is always painful. This is also true of spiritual growth.” I pray, sometimes, that when the beaches completely erode, the clocks drown first.

Monica Uszerowicz is a writer based in Miami, Florida. She has contributed to Hyperallergic, BOMB, The Los Angeles Review of Books, Cultured, Hazlitt, and elsewhere.