Conflict (Process): Alisa Baremboym

Alisa Baremboym met up with artist Tova Carlin to discuss her current show, Conflict (process), at 47 Canal in New York. Below is what precipitated from their conversation about the works in the show and their effect on the viewer.

Conflict is incompatibility. Is it possible to have a clear definition of it? The brain wants to compartmentalize as a method of dissolving conflict. At the same time, we seek connections to assuage our fears of uncertainty. The initial process of conflict is dormant, undefined, until a connection is made that ignites it. When we are presented with an account of conflict, particularly in the form of a written statement, the mechanics of parsing the opposing sides appear as a well-oiled machine. This ostensibly unbiased account expresses incompatibility in abstract terms in order to sidestep actual friction. A synonym of conflict is “war,” a word whose English root comes from the Frankish-German “to confuse.” Conflict in this show is present in the tension of materials, often within a single work, as well as the initial perception of the idea of conflict stemming from an expectation based on the show’s title. The language around this idea of conflict is also interesting because of how something is perceived once it is solidified by language.

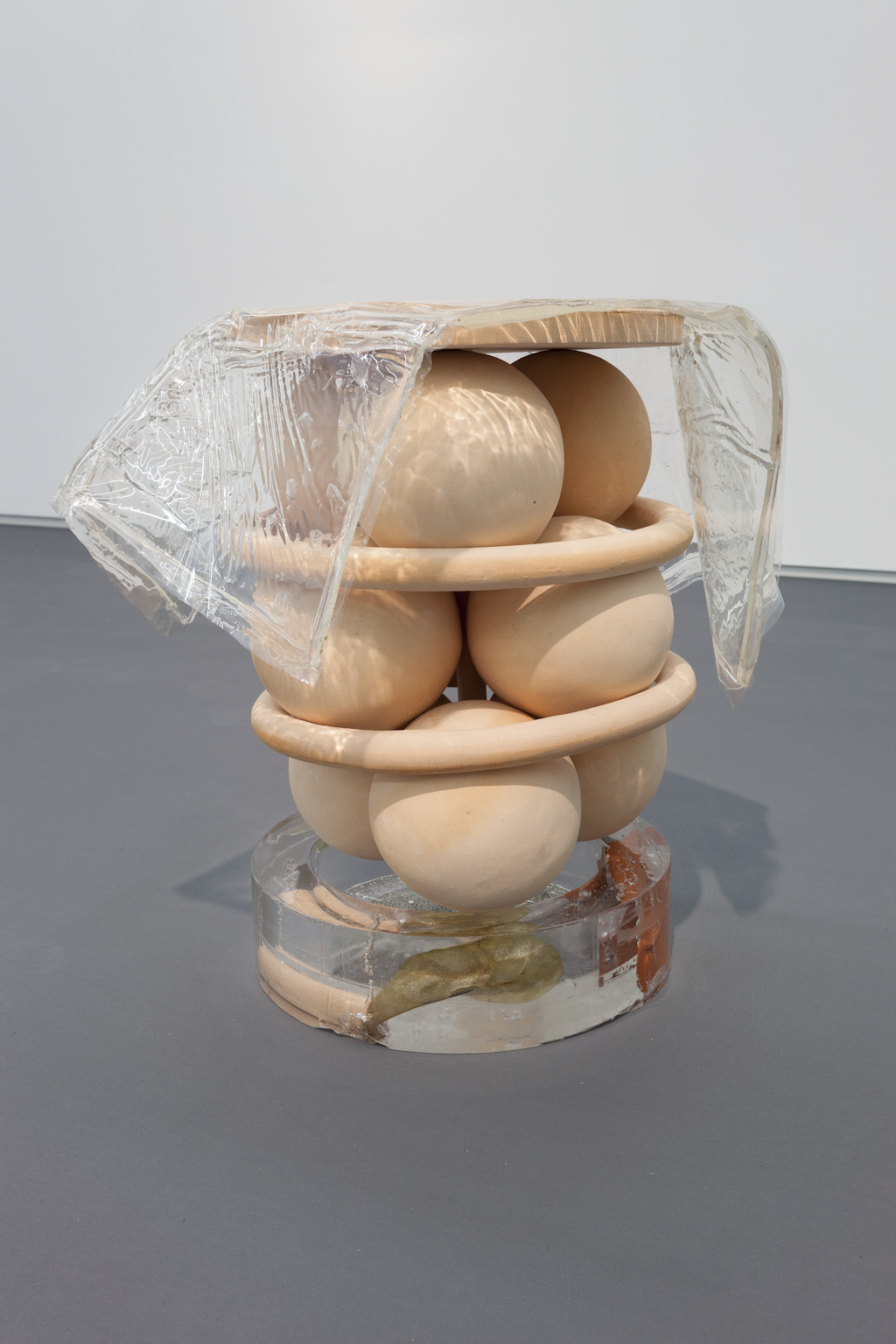

When entering the show, grapeshots are seen scattered throughout the space. They are antecedents to modern weaponry. Their mechanics form the basis for shrapnel shells, though they operate at shorter range. The power of dispersion at close range and the physics of attack in relation to the body highlight the unresolved tension between body and machine, and the point at which the two intersect. Grapeshots are meant to cause lethal harm in intimate detonation scenarios; you necessarily have a more personal relationship to the target. Within the confines of the gallery space, the viewer is never out of range of the grapeshots, which are made of a material and on a scale that narrows the gap between us and them.

Two grapeshots rest in the constructed window bays and push out against stretched liquid vinyl, a material I chose for its filtering of daylight into the interior gallery space. I had windows extended into the gallery in order to highlight the presence of the outside world, while buffering it and keeping it at bay. The black pipes function in a similar way—they allude to the world and its mechanics beyond the immediate environs. The pipes also relate to my earlier suspension works, which create a parasitic relationship to the architecture they occupy.

The spheres, rings, and plates of the grapeshots are hand-modeled, rather than poured into molds. This tactility pulls them away from their origins as industrially manufactured objects; they are rendered in fleshy porous ceramic, a material that mimics the properties of skin and creates an illusion of softness. The spheres have initially attractive and later repulsive qualities. They embody a buoyancy, and the rings seem to barely hold them together. The resin bases are embedded with remnants of ceramic rings and pieces of silk gauze with printed images of drains, industrial shrink-wrapping machines, images of objects impressed into clay, and other bits of ceramic hardware. The bases then hold these fossilized remains of past detonations, a released manifestation of the ceramic shrapnel on top. The centers of the bases hold a soft emollient gel. This gel embodies the possibility of interaction, in this case between the gel and the porous ceramic. In my past works, I’ve used the hydrocarbon gel as an active substance that soaks into the porous ceramic clay bodies and stains them with the petroleum-based mineral oil that is part of the constitution of the gelled emollient.

The uterus is also made of un-vitrified (porous) ceramic; I think of it as sitting like a sink in the steel ramp. It is scorched black, the burn of the process of conflict. It functions as a landscape in the installation. The ramp uses the implication of gravity to provide a visual form of contraceptive. This object’s ominous material qualities also invert the enticing simplicity of biological logic, it is a sort of clinical cross-section taken out of its medical context. The grapeshots perform the reverse visual operation, luring with their modern formal geometry and unnerving with their reveal of lethal utility. There is a cycle of logic that restrains each object from being taken at face value. A subtle confusion occurs in the association of the material properties with the symbolic properties of the uterus and the grapeshot. Each object contains its own polarity.

The space is charged with this polarizing energy. If the uterus is generative, and the grapeshots are destructive, in the same room they pose an initial moment of conceptual opposition, but when taken together as objects with conflicting properties, they begin to approach each other in visual effect. It is a process of perceived conflict that unfolds and shifts when each of the sculptural elements in the show is considered autonomously and in relation to its own inherent logic.

Alisa Baremboym is an artist based in New York. She will be in a show at Glasgow Sculpture Studios as part of the Glasgow International in 2016, and is currently participating in a group show at Künstlerhaus KM—, Austria. In 2014, her work has been included in the Taipei Biennial, Taiwan; Hessel Museum Bard CCS, Annandale-on-Hudson; UCCA, Beijing; Beaux-arts de Paris, Paris; Fridericianum, Kassel; MoMA PS1, Queens; Sculpture Center, Long Island City; as well as in numerous other group exhibitions. This is her second exhibition at 47 Canal.