Changing Cityscapes and the Romance of Bureaucracy: An Interview with Maha Maamoun

Maha Maamoun is a Cairo-based Egyptian artist, curator, and publisher. By playfully and intuitively making images and videos that weave together footage ranging from found YouTube clips of the aftermath of the Egyptian revolution to excerpts from bootleg copies of popular 1950s Egyptian films, she shares stories about common visual culture from an uncommon perspective. One recurring theme within her practice is nature, specifically how it’s seen and interacted with from within the dense metropolitan context of Cairo. Her film Shooting Stars Remind Me of Eavesdroppers (2013), for example, functions as a visual study of the flora and fauna in a public park, soundtracked by a couple’s intimate conversation over a picnic, while her photographic series Cairoscapes (2003), discussed in this interview, investigates the role of (artificial) nature within urban space.

When I called Maamoun, it was the first time we had connected since seeing each other in Cairo in 2016.

Isis Awad: I’d like to talk about Cairoscapes, the first series of photographs you ever exhibited.

Maha Maamoun: This year is actually the 20th anniversary of that project, which is very dear to me. I was taken by other interests since then—one project led to another that engaged the political situation in Egypt—but now that the political horizon is so closed off, I am drawn back to the less overtly political.

How did the series initially begin?

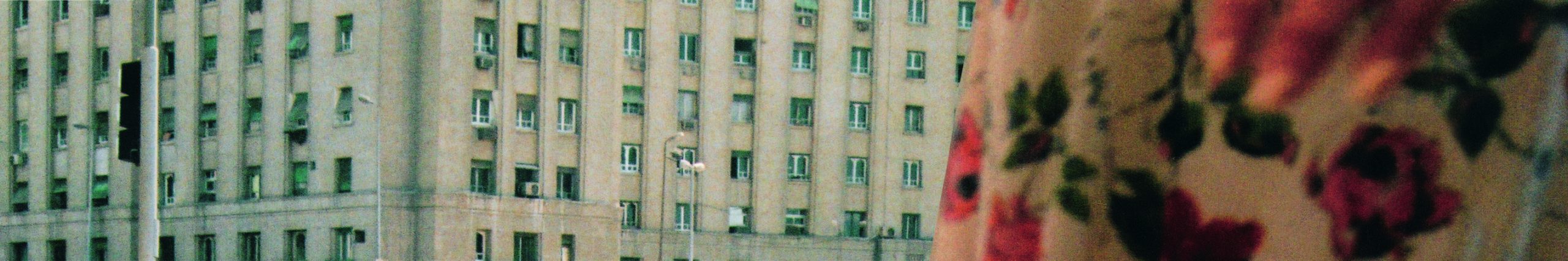

The motivation behind Cairoscapes was trying to find a place to breathe in the city. I’ve lived in Cairo most of my life, and all of my studies and work have been in Downtown Cairo. I was thinking, if there’s no nature in the city and one has to leave to find it, maybe we can mentally trick ourselves into seeing nature. Artificial nature substitutes natural nature all the time. So, I would choose a busy location in the city, for example the heart of Downtown, near the Mogamma el Tahrir, and wait for hours until someone wearing a floral fabric passed by and then take a photo. Those photos became Cairoscapes. There’s something meditative about trying to isolate the (artificial) nature within all the hustle and bustle. You don’t get the sense from these images that there’s a very crowded city all around.

Is the Mogamma still there today?

It’s still there, but it no longer functions as the bastion of Egyptian bureaucracy. It’s empty now.

How important is it for you that the cultural context of Cairoscapes translates to audiences who are unfamiliar with the city?

In some projects translation is more necessary than others. With Cairoscapes, I didn’t feel the need to explain a certain context, because even the Mogamma, as a brutalist building constructed in 1949, is recognizable as an icon of bureaucracy. So, it has equally relevant connotations for anyone. In terms of form, the images also reference a tradition of landscape photography, but in reality, they only capture a fragment of the whole. So apart from a commentary on nature, Cairoscapes was also a commentary on my place and perspective in the city as a pedestrian seeing things at eye level.

The last time I was in Cairo, in 2016, the laws governing photography in public spaces were extremely oppressive and it seems like they have become even stricter now. How has this impacted your practice?

Photographing in the street was never easy, and now it’s even more difficult. I’d really hesitate to take out my camera anywhere in public today. Also, what little nature that existed when I did this project in 2003 has diminished significantly … The city’s expansion through construction has maybe quadrupled. It’s a much tougher city now, exteriorly. So, I’ve been asking myself: Where is respite in the city now and how do I want to connect to it? What is the substitute for nature now? Basically, what would Cairoscapes look like today?

It makes me sad to know that the Mogamma is just an empty shell now. I think there was something romantic about that place, and bureaucracy in general, that now feels lost as most of these processes are moving online. To me, romance encapsulates the highs and the lows, the pain and the reward. It’s similar to the process of moving through bureaucracy to get something done, don’t you think?

Let’s go along with this metaphor … You go to a bureaucratic office and there are many people that you have to interact with, so you’re very self-aware. You’re also desperate and worrying about how you’ll come across and if you’ll say the right thing for them to help. There’s anticipation and waiting—a lot of waiting—and you have to be cool and patient about it.

There’s a sense of courtship.

Yes, you don’t really want to argue right away either, because you’re the weaker half of this relationship. You’re the one who needs something, and you get mixed signals… And yes, all that is changing now with everything centralizing online.

You dealt with a lot of that when making your series The Subduer (2017), didn’t you?

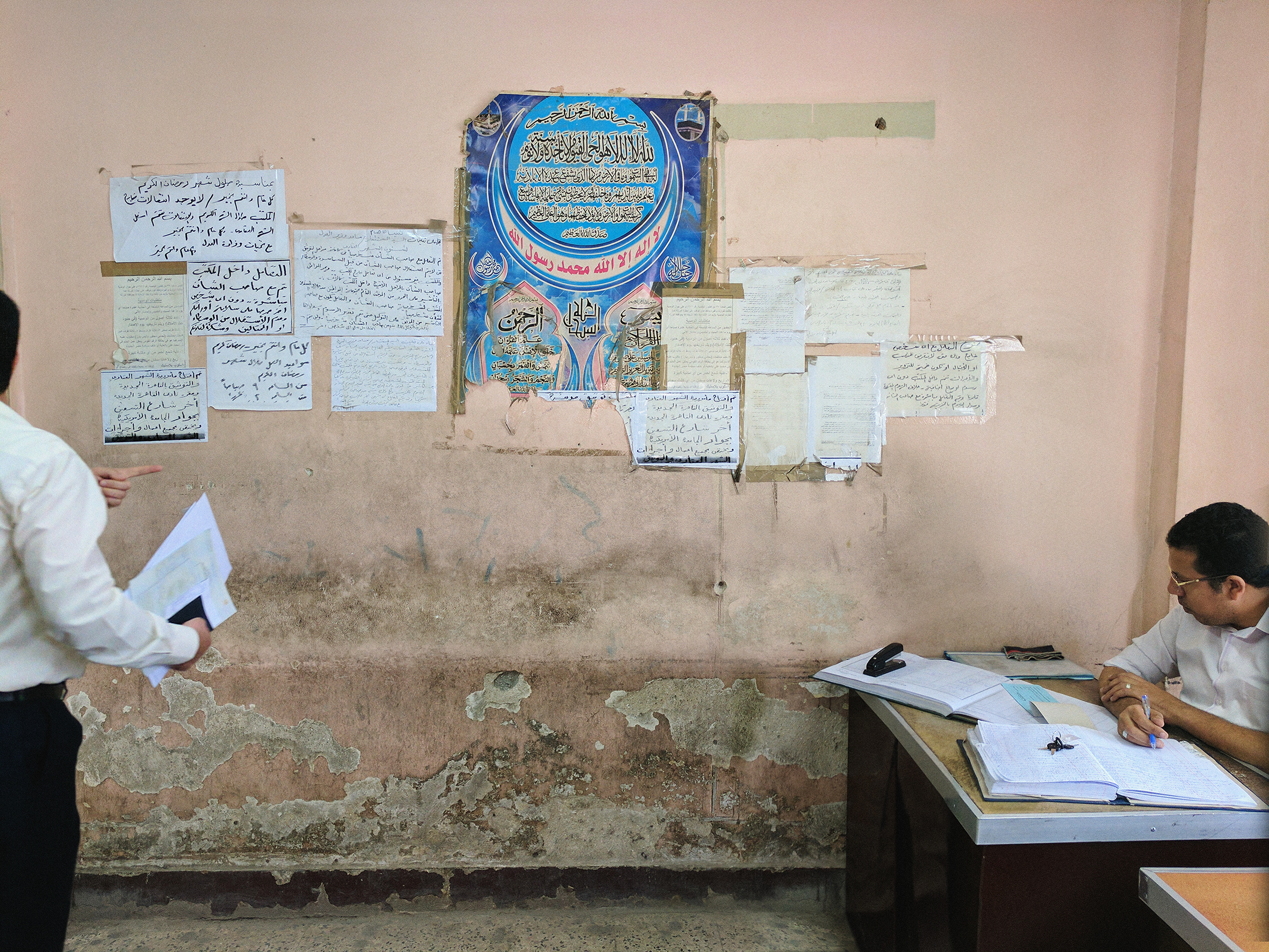

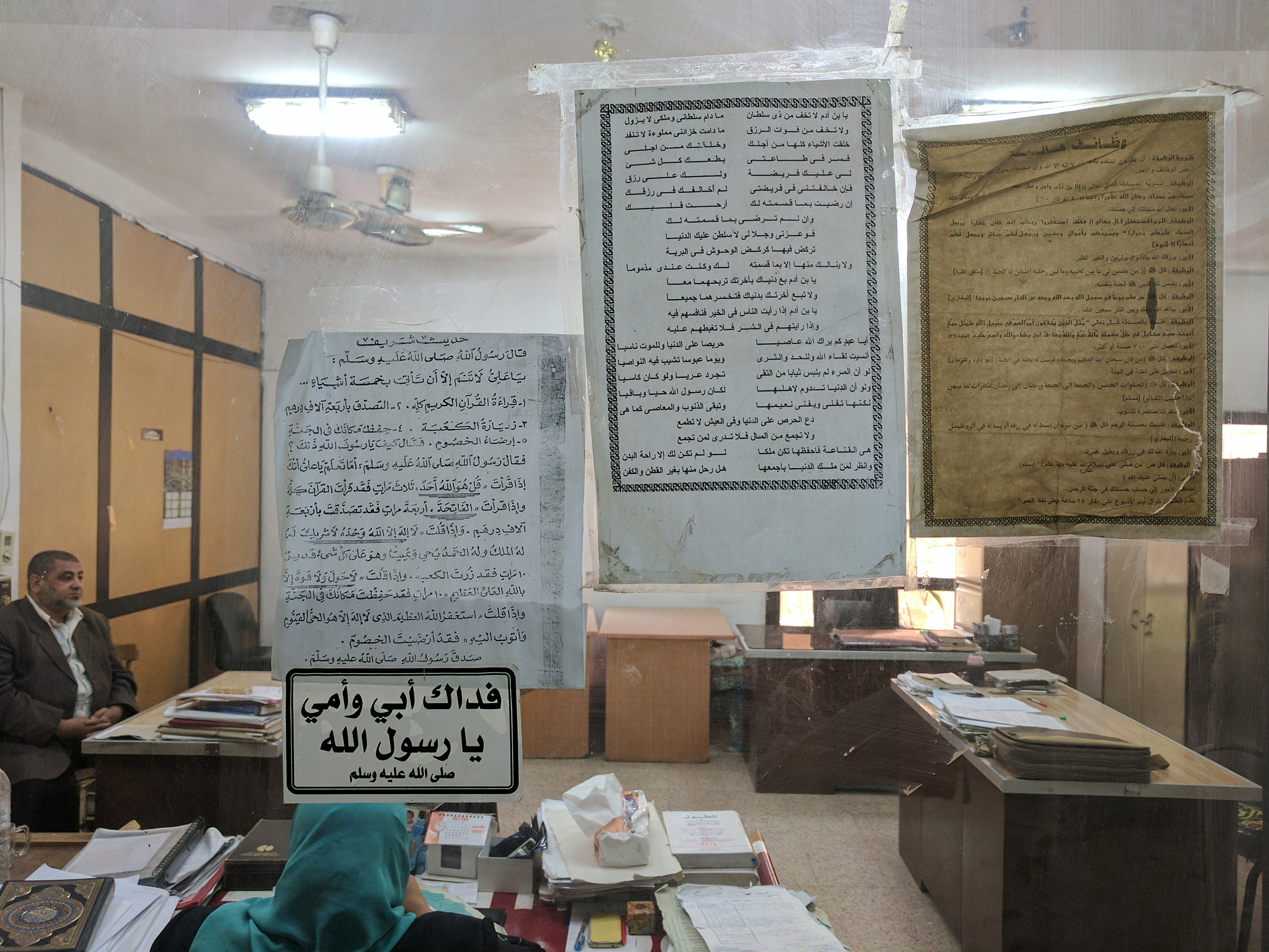

With The Subduer series, I focused on notary offices, which, in Egypt, are a function of the government. When I was working on the series, I was actually trying to obtain power of attorney for my father because he was very ill. So I had to go through the motions myself. While waiting at one of the offices, I noticed a lot of A4 papers with different texts on the walls. Half of them were giving administrative instructions, while the other half were motivational words of wisdom and prayers. There were prayers that you commonly see, but then there were other ones that were at odds with the context: notary offices are all about the exchange of property, but there were a lot of prayers focused on the immateriality and higher meaning of life, or on being patient and suppressing anger.

I felt like these prayers were equally functional instructions, like the administrative ones, for the emotional management of people in the offices. They were put up by the state employees, who are also in a very tough position, having to do their job in less-than-perfect conditions and dealing with a lot of frustration. I felt like these prayers were trying to help manage the anger that can burst out at any moment in these offices.

And to bring it back to nature: after going through all these levels and finally reaching the director’s office to get the final stamp on my paper, instead of instructions and prayers, he had reproductions of nature and landscapes on the walls.

Like reaching Nirvana. Now that these habitats you documented are even more inaccessible, and these bureaucratic offices are all physically changing or no longer there, do you think you will explore different ways of art-making?

I’m now at a very important junction. All my previous work dealt with how we negotiate the public sphere—how it can be suffocating and how we can carve out spaces for ourselves. But now, because of the political situation we are in, which is the toughest I have ever experienced, there’s much less room for self-expression, political opinion, or engagement with questions of citizenship. Freedoms have been diminishing since 2013, and I do not have the ability, energy, or willingness to engage with the risks now entailed [with addressing such topics]. So, for the past few years, I have been engaging with the public through Kayfa ta, the publishing initiative I co-founded with Ala Younis. With that, I have also been wondering if I have to completely change the DNA of my work.

But you know, DNA is always changing anyway. It continues to gather information from our bodies, experiences, and environments. So, maybe your work was never set in stone to begin with.

True. Maybe that just makes it even clearer to me that I have to consistently question where I am in relation to the context I’m in. In Cairo, many artistic conversations and productions are now happening in private spaces. There is the sense that like-minded people need to huddle together, with private spaces offering more flexibility and security: you don’t have to negotiate with anyone or risk any kind of dangerous exposure. So maybe something is changing in our collective DNA. Maybe the question is no longer “how do we engage with the country that is shaped by its politics,” because that has become a very treacherous area, but rather, “where are our thoughts and feelings taking us? How do we nurture them in conversation with each other?”

Isis Awad is a curator, writer, and poet from Cairo, based in New York. She is the Founding Director of Executive Care*, a nonprofit art organization serving queer and trans artists of color from performance and nightlife communities through exhibitions, publishing, and parties.