Carmen Winant Talks The Womyn’s Lands Project of the ’70s and ’80s, Eros Magazine, and Her Most Recent Exhibition “Togethering” in Brooklyn with Jessica Caroline

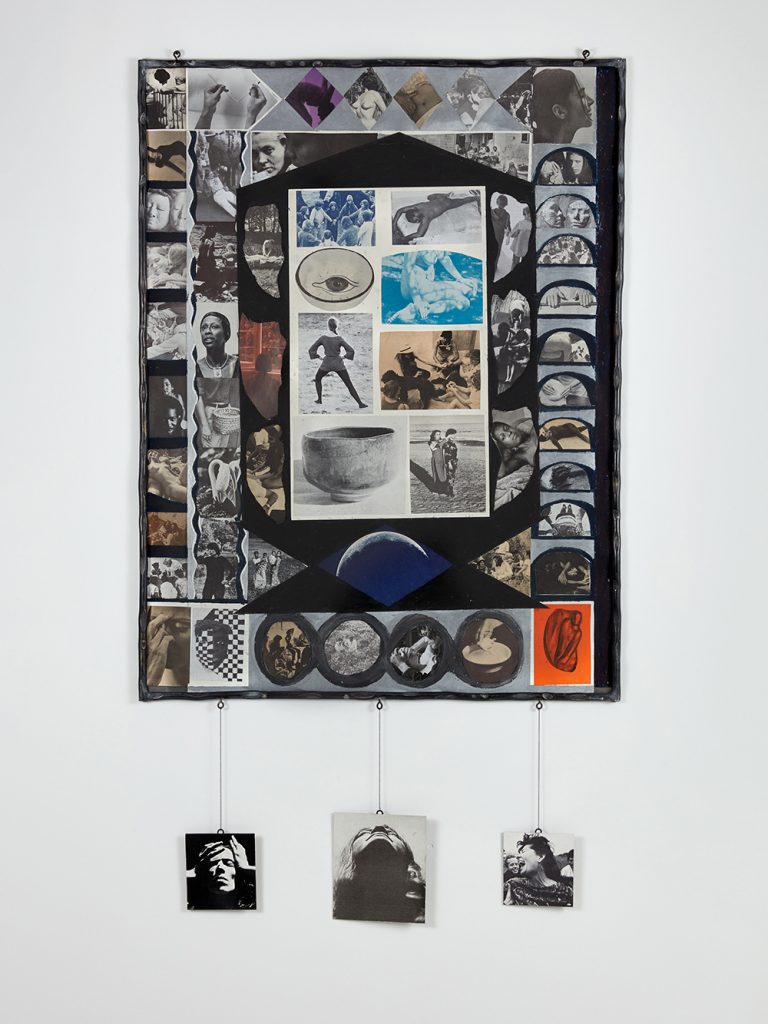

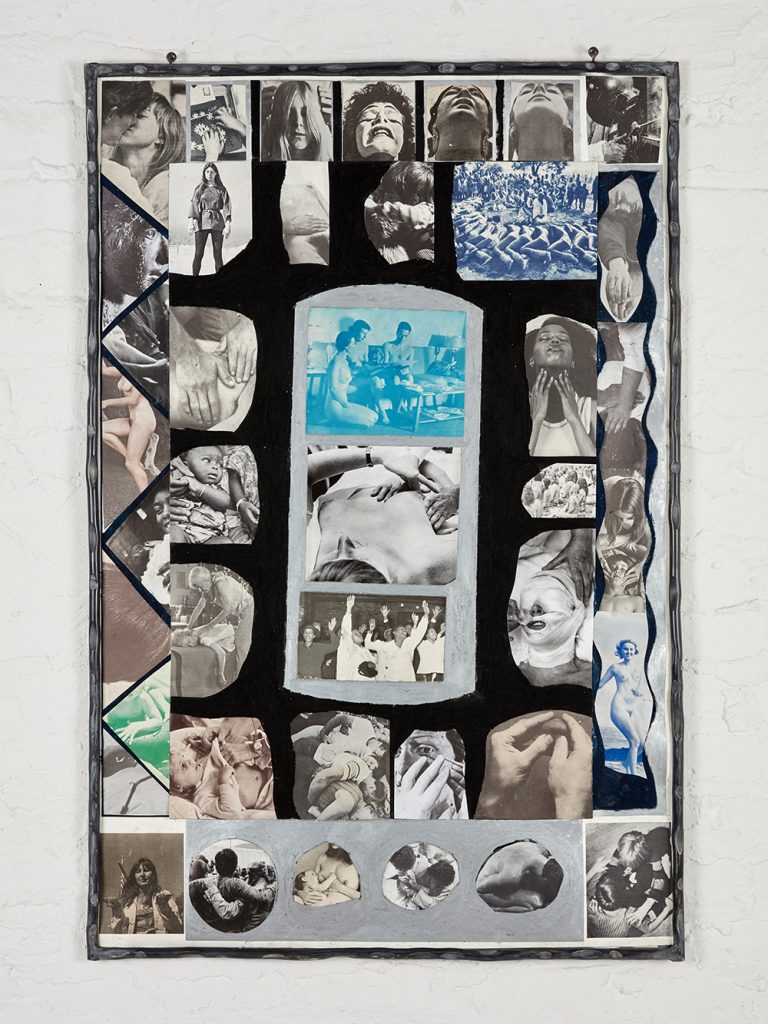

Carmen Winant has carved out a trajectory for herself as an alchemist of archival materials. Her most recent exhibition, Togethering at Fortnight Institute in Brooklyn, conjures generative nodes of signification, in which bodies coexist in various states of repose, threshold, solidarity, and surrender. These collaged inventories are a continuation of earlier work, including an installation titled My Birth at the Museum of Modern Art in 2018, which included over two thousand graphic images of women in stages of labor, and Looking Forward To Being Attacked (2018) at SculptureCenter, featuring images of women engaged in self-defense exercises. There are fragments of unease throughout this work, as well as an insistence that not all is well. Winant’s assemblages, simultaneously reductive yet expansive maps of humanity, lean into spirituality without the promise of transcendence.

I spoke to Winant about her inspiration for Togethering at Fortnight Institute in September 2020.

Jessica Caroline: Could you talk about your chosen title?

Carmen Winant: The title comes from a word invented by lesbian separatists in the 1970s and ’80s. The project that I was working on before this one, Notes on Fundamental Joy, was centered on the womyn’s lands of the Pacific Northwest.

Much of my own exploration was centered on how these women used certain tools at hand—photography and language itself—to create new systems of sight and worth outside of, and beyond, patriarchy. They took new surnames (Hillwoman, Mountaingrove, Freedom, etc.), invented new words like herstory and moonstration, and created verbs like “visioning” and “togethering.” I was really struck by that last word in particular, which implies that being together was an active state in this way, you know? It isn’t something that happens to us, we become and inhabit it. The work is not “about” the womyn’s lands, but it does obliquely come from and reference back to that source: awakening through each other.

You made it clear in your artist statement that you are coming to this body of work from a secular point of view. Through these transcultural and transhistorical points of view, you appear to be divining a cosmic entanglement of ecstatic sentiments that are estranged from their original context, yet familiar in their emotive essence. Can you speak to the cosmological and spiritual aspects of your work?

On my studio wall hangs a page ripped from a book, picturing a group of women making mandalas. I don’t know if it’s a consciousness-raising group or what; I vaguely remember that it is from a book on healing. I love the image and the few small ones beneath it: close-ups of the mandalas themselves. I’ve often thought about using the image as a reference somehow, but I never knew how. I was worried that it would feel too New Age to pull from them and that the reference might feel too specific. For the reasons you suggest, it seemed like a way, as a secular person with a secular view of the world, to approach a subject matter that called up something ineffable between us, something like energy. The mandalas are really good at this, creating physical expressions of some profound internal order, something that resembles the cosmos.

This exhibition can be viewed as an extension of your photographic installations My Birth (2018), Looking Forward to Being Attacked (2018), and Pictures of Women Working (2017). In this installation, you leave out the text so that the images float freely without context. Tell me a little more about that choice.

Yes, most simply put, I am interested in deconstructing the implicit value hierarchy between images and text. We read words as doing the “real” work, captioning or holding up the image, proffering explanation. I want to strip away the explanation. Or rather, I want images to behave as their own kind of explanation. When I do use text—as with My Birth, the book—I wanted to create a kind of inverse scenario, in which images can hold information and text can be read as an image. Likewise in Notes, the essay ran across the bottom of all the pages as a single line—a kind of low-lying landscape.

Many images struck me as familiar and unrecognizable. You have included an iconic image of a biracial couple from a photo essay by Ralph M. Hattersley Jr. featured in Ralph Ginzburg’s Eros magazine. These images were the subject of a freedom-of-speech trial that saw Ginzburg imprisoned in 1972 under charges of “obscenity.” I’m curious as to why you chose the profile image of the couple, and why you chose the form of a handshape that dangles from a collage.

Yes, good eye! I bought four issues of Eros magazine some years ago, in a bookstore that was going out of business in Indiana; they were in perfect condition. I generally try to avoid using familiar images or figures, but in some cases, I can’t resist.

Your work is constantly bringing the viewer back to the erotics of touch, making us aware of your own hand as an interface—a toolmaker as much as a sense-maker—transmitter and receiver. There is a reckoning at stake beyond solitary creation, reaching beyond the self. How much is the tactile process of cutting and pasting seemingly unrelated or disconnected signifiers important for you, and how do you consider the analog process of image-making, cutting, juxtaposing to be significant?

I find myself wanting to draw work closer to feeling—which is not a new idea. The show I mentioned, at 14a, began by watching my young son trace the outline of his own hand, over and over, and considering the way that we feel our bodies together—constantly, together—and in relation to the world. What are the contours, the bleeds?

There are a lot of ways to address what you are asking. Yes, the fact that I touch every image—that I rip out and cut them and handle them, sometimes for years at a time—has something to do with both what is in the images and the ways in which the images then, subsequently, touch each other. I am touching photographs touched by many hands before my own; that history is inscribed upon them and alludes to an invisible transmission between us. It is all part of the exercise of togethering.

We’re at a moment in time where togetherness is fraught, where competing values and material interests are at stake. The two-party system has left many voters disenfranchised between a rock and a hard place. To what extent do you allow for activism and politics to enter into your work?

My artwork is a channel for my politics—for my feminist consciousness—and not the other way around. I do struggle with the potential of art-making as an effective political force. I don’t want to flatten experience into metaphor, package it cleanly for a press release. So this is a hard question for me to answer. That is to say: I don’t struggle with the decision to make work about and through my values, but I do struggle with its relative potential impact. I generally find that it is in conversations like these ones, as well as countless conversations with students—my own and other peoples’—that some hard work is done.

I believe in the power of the radical, alloyed group. I believed in it when it came to women’s liberation, I believed in it when it came to Occupy, I believe in it now, when it comes to Black Lives Matter. None of this is ever perfect, of course. Movements lose their way for so many reasons, radicality can be co-opted by consumerism, and solidarity can reveal itself to be something symbolic rather than actionable. But ultimately, being together in this way has such emancipatory promise. It is how we survive and also how we build our world.

Jessica Caroline is a freelance writer/poet/performer currently based in New York.