Canadian Art Institutions and Diasporic Indigenous Histories: A Case for Dissenting Voices

In keeping with this year’s focus on asking writers to respond to the various ways censorship manifests in the art world, our second commissioned text is by Sarah Edo, an emerging writer and curator based in Toronto, Canada. Edo’s piece is inspired by recent events at the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO), Toronto’s second largest museum, and among the largest in North America. She uses the controversy surrounding the recent departure of Anishinabe curator Wanda Nanibush—the museum’s first curator of Indigenous art—as a point of entry into a broader historical read of how Indigenous voices have been presented, supported, and silenced in Canadian institutions.

At the core of Edo’s argument is the belief that museums and art institutions are most effective when they treat exhibitions as spaces for discourse, conversation, and dissent—both inside and outside of the institutional walls. With solidarity between Canada’s Palestinian diaspora and its First Nations population serving as a backdrop, Edo starts in 2023 and takes us back to 1988 to consider the weight and influence of political activism in the arts. The Indigenous voices that Edo weaves together are myriad, from institutional curators such as Wanda Nanibush and Taqralik Partridge, to Palestinian-Canadian artists such as Rehab Nazzal, to the Lubicon Lake Cree activists who protested the landmark Glenbow Museum exhibition The Spirit Sings. Edo’s research presents several throughlines for consideration, exploring how Canadian institutions’ presentation of work by Palestinian and First Nations voices has been shaped by the legacy of colonialism, ongoing cultural insensitivities, the reality of illegal occupation, and the still ever-present threat of censorship and removal.

— Ebony L. Haynes, 2024 EIR

For those of us living in the belly of the empire, what time is it on the clock of the world? I borrow this question from writer adrienne maree brown, who borrows it from philosopher Grace Lee Boggs, to ask in earnest: are we at a political tipping point in the arts, and further, what is required of us in this present moment? While art institutions pride themselves on leading progressive conversations globally, now more than ever, we are witnessing heightening contradictions and the iron grip of censorship, conservatism, and repression across the field.

Since October 7th, 2023, there has been a notable increase in public political consciousness about Western imperialism and the ways in which it sustains genocidal and colonial violence across the Global South. The demands for and against a liberated Palestine, in particular, within the global, social, and contemporary arts landscape expose the political positions of institutions and the people embedded within them. While there have always been waves of political uprisings that reveal mainstream society’s orientation toward unfreedom, the urgency and scale at which the past ten months have ushered in clear political demands that confront institutions, corporations, and governmental entities is staggering.

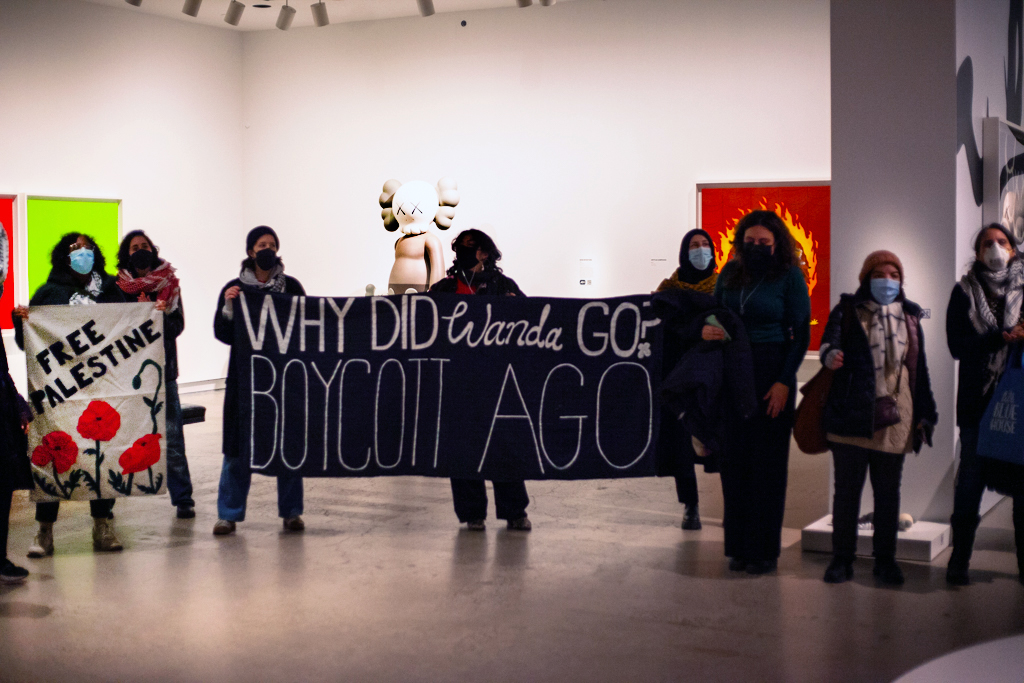

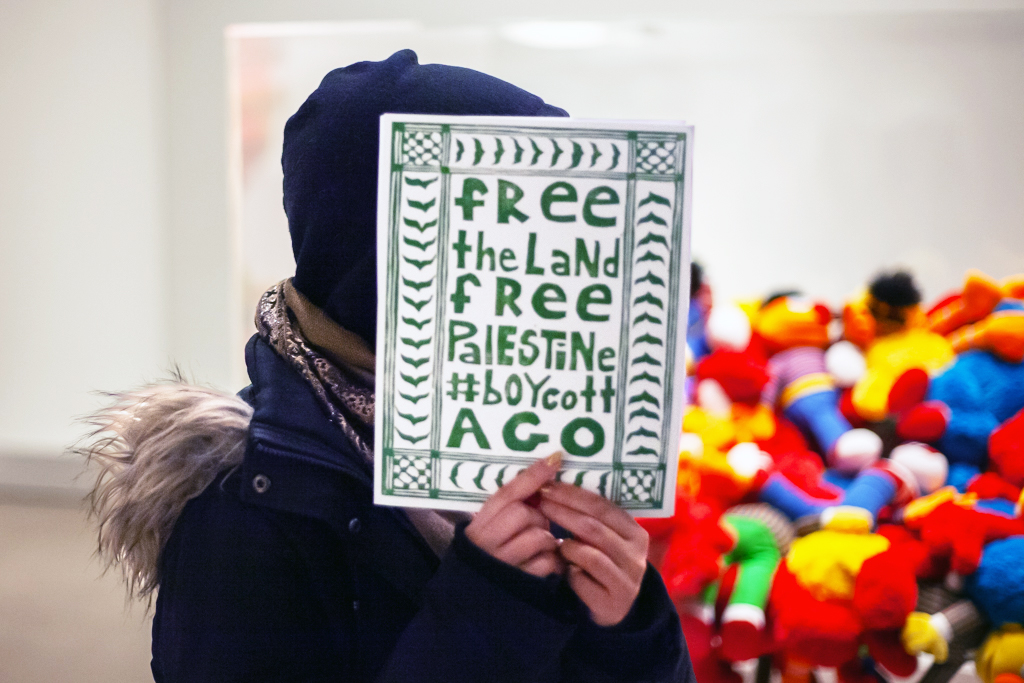

For nearly one year, like many metropolitan cities, Toronto has seen recurring protests and calls to action demanding change in policy from both the Canadian government and private corporations that have been actively supporting or silently complicit in Israel’s officially ruled illegal occupation of Palestine and the continued aggressive attacks in Gaza.1 Art institutions have certainly not been exempt from the public’s pressure and demands for accountability, especially in regard to their sources of corporate funding, which often have financial ties to weapons manufacturing companies.2 While most art institutions were facing external scrutiny for either remaining silent or releasing blanket statements about the war in Gaza, November 2023 saw a turning point in Toronto’s art activism, when protests erupted after speculations spread on social media that Wanda Nanibush, the inaugural Curator of Indigenous Art at one of Canada’s largest museums, the Art Gallery of Ontario’s (AGO), had suddenly departed from the museum.3

“Art institutions have certainly not been exempt from the public’s pressure and demands for accountability, especially in regard to their sources of corporate funding, which often have financial ties to weapons manufacturing companies.”

Nanibush was heralded for being the first Anishinaabe curator at the AGO, where she stewarded exhibitions and retrospectives of various Indigenous visual and performance artists, such as Robert Houle, Rebecca Belmore, and Rita Letendre. Her curatorial appointment at the AGO marked an important moment for the museum, as it coincided with the launch of the Indigenous and Canadian Art department. While Nanibush never commented on the reason for her departure, speculations about censorship arose after the leaking of a letter written by the members of the Canadian Israel Friends of Museum, addressed to Stephan Jost, the CEO of AGO, which targeted Nanibush and characterized her pro-Palestinian personal political views as “inflammatory, inaccurate rants against Israel.”4

The letter insisted that AGO adopt the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) definition of antisemitism, which would essentially foreclose any criticisms or interrogation of the state of Israel by equating those criticisms with antisemitic rhetoric. Nanibush’s abrupt departure from the AGO, followed soon after by Taqralik Partridge, the only other Indigenous curator at the museum, has been cause for widespread criticism and concern among Canadian art communities. In addition to the on-site demonstrations that have occurred both within and outside the AGO, many esteemed arts leaders have expressed their disappointment over this decision online, with over 3,500 artists, curators, and cultural workers signing a letter committing to boycott the museum.5 In a public letter released on January 17, 2024, the Indigenous Curatorial Collective contends that the AGO’s decision to dismiss Nanibush is “an incredible step backward that is so damaging, not only to the Indigenous arts community, but other racialized arts communities as well.”6 The Collective urged that in order to regrow relations with their community, the AGO would need to release Nanibush from any legal obligations, such as an NDA, that might prevent her from speaking about her dismissal. Non-disclosure agreements (NDA) are confidentiality contracts commonly used in arts institutions, which prevent both current and former employees from sharing information about their work. In some cases, an NDA is used to protect intellectual and trade property, but in other instances, it can be an oppressive tool that limits any critique or circulation of knowledge about unjust labor practices and conditions. Furthermore, after months of protests targeted at the museum and its censorship practices, over four hundred AGO workers launched a historic month-long strike, addressing the pay inequity and precarious working conditions for part-time workers at the museum. During the strike, it was revealed that the AGO Foundation paid Jost over $390,000 in consulting fees in addition to his annual salary of $406,000.7

The symbolic violence of an Indigenous curator being silenced for speaking out against the illegal occupation of Palestine is cruelly ironic, yet unsurprising, given the museum’s commitment to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Report, a mandate that purports to acknowledge and rectify the historical injustices experienced by the Indigenous population in Canada through the adoption of reconciliation practices. In her essay The State is a Man, Kahnawà:ke Mohawk scholar Audra Simpson reminds us that Canada often thinks itself to be an exception to the colonial legacy of racism and white supremacy because of the recognition and reconciliation efforts made toward Indigenous peoples, when in actuality, “Canada is simply a settler society whose multicultural, liberal and democratic structure and performance of governance seeks and ongoing ‘settling’ of this land.”8 If in the words of Jost, “the AGO remains fundamentally and fully committed to showing, acquiring and programming Indigenous art, voices, and stories,”9 while simultaneously censoring an Indigenous curator for speaking about the sovereignty of Palestinians, then the commitment to the commission report remains severely compromised.

“In her essay ‘The State is a Man,’ Kahnawà:ke Mohawk scholar Audra Simpson reminds us that Canada often thinks itself to be an exception to the colonial legacy of racism and white supremacy because of the recognition and reconciliation efforts made toward Indigenous peoples, when in actuality, ‘Canada is simply a settler society whose multicultural, liberal and democratic structure and performance of governance seeks and ongoing “settling” of this land.’”

Over the past year, the rate by which both Palestinian and non-Palestinians artists who have drawn attention to Gaza and the illegal occupation of Palestine, have been censored is cause for grave concern, yet this is far from a recent phenomenon.10 This moment of heightened repression is a part of a long tradition of silencing narratives from and within Palestine. Nearly ten years ago, Palestinian-Canadian artist Rehab Nazzal was the target of censorship when her solo exhibition Invisible (2014) opened at the Karsh-Masson Gallery in Ottawa, Ontario. The exhibition, comprised of video installations and photographic prints, explored the obscured narratives of human rights violations in occupied Palestine. She incorporated her family’s archives, sharing deeply traumatic stories of injustice and inconsolable grief. Mourning (2012) tells the story of how her brother, Khalid, was extra-judicially assassinated by an unidentified murderer in Athens in 1986. The film shows footage of her brother’s funeral and the massive protest that broke out after the identity of his killer was left undisclosed, and Israel refused to let her brother be buried at home. Growing up under occupation in Palestine, Nazzal directly speaks to the devastating effects of dispossession, expulsion, and the controlling, destructive, and punitive measures of the military occupation. Unfortunately, shortly after the opening, Rafael Barak, the Israeli ambassador to Canada, attempted to censor the exhibition and flag the work as “glorified terrorism.” According to the artist, Barak rallied conservative lobby groups and even tried pressuring the mayor of Ottawa to investigate the juried art selection process.11 While the ambassador was unsuccessful in censoring Nazzal’s exhibition, these attempts to silence and intimidate the artist’s work is ultimately part of a greater endeavor to stifle information about severe human rights violations in Palestine.

Here, I am compelled to think with Reesa Greenberg about the political and transformative possibilities of the exhibition sites. In her 1995 essay, “The Exhibition as Discursive Event,” she encourages readers to consider the exhibition as a discursive event, and as an expression of “the oral rather than the written; the social rather than the individual; the poetic rather than the predictable.”12 Art historian Diana Nemiroff further contextualizes Nazzal’s work within the realm of public space, and the complexity of holding divergent political discourse through public art programming. Nemiroff evokes Greenberg’s prompt: what would it mean to evaluate the success of an exhibition not through its aesthetic value, but through how much discussion it generates, and to what effect. In Nazzal’s case, the exhibition was a catalyst for a broader discussion about artistic freedom of expression and the suppression of public discourse about the resistance against military occupation and the ongoing struggle for Palestine’s liberation. For Nazzal, this exhibition also exposed her to the Canadian mainstream media and the pervasive prejudices undergirding Arab representation in the West since the 9/11 attacks.

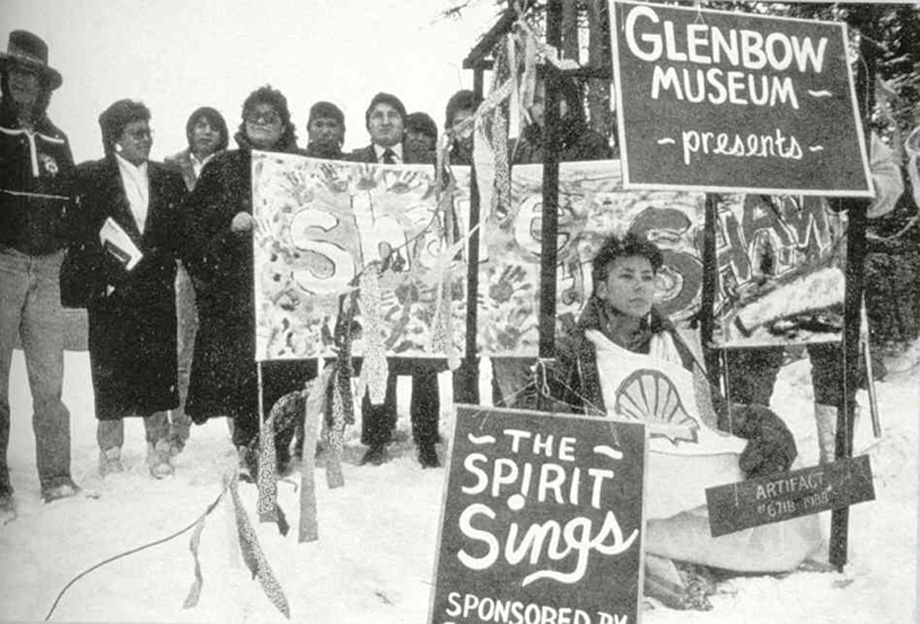

Three decades before Nazzal’s Invisible, the Glenbow Museum in Calgary, Alberta opened an exhibition that was celebrated as much as it was critiqued. The Spirit Sings: Artistic Tradition of Canada’s First People featured over 650 First Nations and Inuit objects and artifacts drawn from public and private collections. Launched during the 1988 Winter Olympics in Calgary, the exhibition was meant to “provide a platform to educate Canadians about Indigenous cultures and heritages.”13

However, there was an overwhelming critical reaction against this exhibition led by the First Nations community. Upon the announcement of The Spirit Sings, Lubicon Lake Nation, a Cree First Nations in northern Alberta, organized a boycott of the exhibition, aiming to draw attention to issues on land disputes and Indigenous representation. In the late 1800s, during the establishment of the Treaty negotiations between the Crown and Indigenous groups, an oversight occurred with Lubicon Lake Cree, which left them on unceded land, without Treaty protection, for decades. During this time, the Canadian government leased oil and gas wells on their land, which made their hunting and fishing areas vulnerable to the effects wrought by pipelines, making their population even further susceptible to communicable disease and contaminated water.14 This ensued decades-long land disputes between Lubicon Lake Cree and the Canadian government. Lubicon Lake Cree chose to use the heightened tourist attention brought to the province by the Olympics as an opportunity to boycott the exhibition and refuse the representation of Indigenous culture the museum purported to showcase, and instead directed the public’s attention to the conditions of the illegal occupation and the implications of gas and oil pipelines on their land and communities.15

Indigenous communities and allies’ resistance to this exhibition spurred critical conversations about museological and collecting practices, historical inaccuracies, and cultural insensitivities, as well as the federal government’s response to Indigenous land rights and representation. After all, many of the Indigenous art and artifacts collected by museums are stolen or forfeited objects, acquired during the ongoing settler colonial conditions that have displaced, dispossessed, and disappeared Indigenous peoples.16

The political action against the exhibition went on to inspire Indigenous curators and artists, including Mohawk curator Lee-Ann, who writes extensively on the politics of inclusion, visibility, and the ethics of museological practices in “Turning the Page: Task Force Report on Museums and First Peoples,” published in 1992, and “The Politics of Inclusion and Exclusion: Contemporary Native Art and Public Art Museums in Canada,” a report published for the Canadian Arts Council in 1991. These documents not only critically interrogated exhibitions like The Spirit Sings, they also became foundational guides for how to increase Indigenous peoples’ involvement in how to interpret their own cultural artifacts; how to appropriately repatriate cultural artifacts; and how to improve access to museum collections for Indigenous peoples. Although these reports were published in the 1990s, they remain relevant to art institutions and their practices to this day. In their presentation for the “Thoughts on Freedom” speaker series, curator and critic Vince Rozario discussed how appealing to a class of wealthy patrons to fund the arts ultimately influences the ways in which political subject matter gets taken up in art. Paraphrasing the writer Mitch Speed, they noted that artists creating political artwork “have to have a degree of intellectual and cerebral remove, an ironic detachment that is converted into a kind of abstraction, or has to link back to a formal question about something … that is supposed to supersede material relations.”17

Rozario emphasized how political neutrality, or in this case, explicit censorship, can be countered through practice and organized movement. Similar to the political potential of exhibitions, AGO’s censorship has served as a watershed moment and catalyst for widespread organizing in the arts, with the rapid development of several ad-hoc collectives, including the No Arms Against the Arts coalition, which consists of Artists Against Artwashing (AAA), Writers Against the War on Gaza (WAWOG), Film Workers for Palestine (FWP), and CanLit Responds, which have all been calling upon art and academic institutions to heed the guidelines set forth by the Palestinian Academic and Cultural Boycott of Israel, which include “making a public commitment to refuse material support from the state of Israel and to reject projects that normalize Israel’s forced dispossession of Palestinians.”18 Since November 2023, these collectives have been organizing actions and programs addressing various arts institutions and their censorship practices, while also addressing funding partners that have direct connection to Israel’s military occupation of Palestine. These counter-programming efforts, which include film screenings, vigils, and discussions that take place across artist-run centers, public parks, and even student-led encampment sites, are generative events that facilitate solidarity building across movements within anti-colonial organizing in Toronto. Most recently, WAWOG and FWP precepted the Hot Docs Canadian International Documentary Festival by holding their own counter-program festival, No Arms in the Arts, featuring films, talks and actions that draw attention to the funding support of Scotiabank and its investments in Elbit Systems, the corporation producing arms weapons manufacturing for the Israeli Defense Force.19

On May 15, 2024, WAWOG announced that since October 2023, Scotiabank’s 1832 Asset Management has reduced its stake in Elbit from 5.1% to 2.5%, which represents a divestment of nearly $250 million dollars.20

These organizing efforts are not only shedding light on the ways in which oppressive censorship tactics are connected to the ecology of funding structures and stakeholder relationships in the Toronto arts landscape, but are also demonstrating that it is possible to imagine and fund our work without recourse to the death and destruction of people. From the 1980s to the present, the dilemma of how arts institutions attempt to incorporate, represent, and respond to local and global Indigenous worldviews has often led to failure: failure that unveils the unsustainable, and at times harmful, nature of institutional policy and programming reforms. Arts and cultural institutions are not exempt from colonial thought and structure, but often reify it through cultural production, which is linked to a nationalist, Euro-centric and patriarchal agenda. And yet, as Lakota organizer and historian Nick Estes writes, “as colonialism changes throughout time, so does [Indigenous] resistance to it.”21 Like the Lubicon Lake Nation demonstrations against the The Spirit Sings exhibition, and the current Palestine solidarity organizing in the Toronto arts community, artists and cultural workers are drawing out the connections between settler colonial strategies and arts and cultural production, and the ways in which all of us are implicated. More importantly, they are demonstrating what we can practically do to support Indigenous resistance to military occupation and settler colonialism, from Turtle Island to Palestine.

Sarah Edo is a curator and writer born and based in Tkaronto/Toronto. She has curated exhibits and programs with BAND Gallery, Images Film Festival, Whippersnapper Gallery, Lakeshore Arts, and the Gardiner Museum. Her art writing has been featured in Studio Magazine, BlackFlash Magazine, CMag, and Gallery 44. She holds a Bachelor of Arts degree in Gender and Cinema Studies, as well as a Masters in Gender Studies, from the University of Toronto.

NOTES

1. Raffi Berg, “UN top court says Israeli occupation of Palestinian territories is illegal,” BBC, July 19, 2024, https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cjerjzxlpvdo.

2. Hannah Black, Tobi Haslett, Ciarán Finlayson, “The Tear Gas Biennial,” Artforum, July 17, 2019, https://www.artforum.com/columns/a-statement-from-hannah-black-ciaran-finlayson-and-tobi-haslett-regarding-warren-kanders-and-the-2019-whitney-biennial-244098/.

3. Karen H. Ko, “ Indigenous Art Curator Wanda Nanibush Leaves Art Gallery of Ontario, Prompting Questions,” ARTnews, November 22, 2023, https://www.artnews.com/art-news/news/wanda-nanibush-indigenous-art-curator-art-gallery-of-ontario-1234687592/.

4. Maya Pontone, “Questions Arise as Indigenous Curator Suddenly Departs Toronto Museum,” Hyperallergic, November 21, 2023, https://hyperallergic.com/857994/questions-arise-as-indigenous-curator-wanda-nanibush-suddenly-departs-toronto-art-gallery-of-ontario/.

5. Jo Lawson-Tancred, “Fallout Over the Surprise Departure of Art Gallery of Ontario’s Indigenous Curator Escalates,” artnet, January 24, 2024, https://news.artnet.com/art-world/fallout-over-the-surprise-departure-of-art-gallery-of-ontarios-indigenous-curator-escalates-2422632.

6. “Let Wanda Speak,” Indigenous Curatorial Collective, June 4, 2024, https://icca.art/let-wanda-speak/.

7. Rachel Goodman, “‘The gallery is shortchanging staff,’ Hundreds of AGO workers are striking over pay and contracts,” NOW Toronto, March 26, 2024, https://nowtoronto.com/news/the-gallery-is-shortchanging-staff-hundreds-of-ago-workers-are-striking-over-pay-and-contracts/.

8. Audra Simpson, “The State is a Man: Theresa Spence, Loretta Saunders and the Gender of Settler Sovereignty,” Theory & Event; Baltimore

19, no. 4 (2016).

9. Josh O’Kane, “Art Gallery of Ontario’s associate curator of Indigenous art, Taqralik Partridge, departs,” The Globe and Mail, January 25, 2024, https://www.theglobeandmail.com/arts/article-ago-indigenous-curator-taqralik-partridge/.

10. Valentina Di Liscia, “Have Pro-Palestine Artworks Been Censored in Your State?,” Hyperallergic, May 22, 2024, https://hyperallergic.com/917340/ncac-pro-palestine-artworks-been-censored-in-your-state/.

11. “Israeli embassy upset over art exhibit at Ottawa City Hall,” CBC News, May 23, 2014, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/ottawa/israeli-embassy-upset-over-art-exhibit-at-ottawa-city-hall-1.2652633.

12. Reesa Greenberg, “The Exhibition as Discursive Event,” in Longing and Belonging: From the Faraway Nearby (SITE Santa Fe: 1995), 120.

13. Quyen Hoang, “First Nations People Mining the Museum: A Case Study of Change at the Glenbow Museum,” MA thesis (Concordia University, 2003).

14. Penny Kome, “Lubicon Lake Cree sign historic land claim settlement,” Rabble, November 16, 2018, https://rabble.ca/indigenous/lubicon-lake-cree-come-cold/.

15. Dan Dibbelt Calgary, “Nations gather to protest Glenbow’s Spirit Sings display,” Windspeaker 5, no. 23 (1988): 2.

16. Tawyna Plain Eagle, “Millions of Indigenous artifacts are still on display in museums around Canada,” CBC, June 2, 2023, https://www.cbc.ca/television/millions-of-indigenous-artifacts-are-still-on-display-in-museums-around-canada-1.6863670.

17. Rozario, Vince, “A recording of my talk for the ‘thoughts on freedom’ series!,” Instagram, July 15, 2024, https://www.instagram.com/spicydiscourse/reel/C9fQA2ZA6HI/.

18. Shiv Kotecha and Rainer Diana Hamilton, “PACBI Now,” The New Inquiry, November 26, 2023, https://thenewinquiry.com/pacbi-now/.

19. Maya Pontone, “Canadian Arts Funder Faces Pressure to Divest From Israeli Weapons Supplier,” Hyperallergic, March 26, 2024, https://hyperallergic.com/880414/canadian-arts-funder-scotiabank-faces-pressure-to-divest-from-israeli-weapons-supplier/.

20. Nivedita Balu, “Scotiabank’s fund unit halved stake in Israeli weapons maker Elbit, filing shows,” Reuters, May 14, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/business/finance/scotiabanks-fund-unit-halved-stake-israeli-weapons-maker-elbit-filing-shows-2024-05-14/.

21. Nick Estes, Our History Is the Future: Standing Rock Versus the Dakota Access Pipeline, and the Long Tradition of Indigenous Resistance (New York: Verso, 2019), 21.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Estes, Nick. Our History Is the Future: Standing Rock Versus the Dakota Access Pipeline, and the Long Tradition of Indigenous Resistance. New York: Verso, 2019.

Garlington, Tyra. “What time is it on the clock of the world? Adrienne Maree Brown, Emergent Strategist shares her view.” Tyra Garlington. January 20, 2024. https://tyragarlington.com/what-time-is-it-on-the-clock-of-the-world-adrienne-maree-brown-emergent-strategist-shares-her-view/.

Goodman, Rachel. “‘The gallery is shortchanging staff,’ Hundreds of AGO workers are striking over pay and contracts.” NOW Toronto, March 26, 2024. https://nowtoronto.com/news/the-gallery-is-shortchanging-staff-hundreds-of-ago-workers-are-striking-over-pay-and-contracts/.

Greenberg, Reesa. “The Exhibition as Discursive Event.” In Longing and Belonging: From the Faraway Nearby, 120–125. SITE Santa Fe: 1995.

Hoang, Quyen. “First Nations People Mining the Museum: A Case Study of Change at the Glenbow Museum.” MA thesis. Concordia University, 2003.

“Israeli embassy upset over art exhibit at Ottawa City Hall.” CBC News, May 23, 2014. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/ottawa/israeli-embassy-upset-over-art-exhibit-at-ottawa-city-hall-1.2652633.

Kome, Penny. “Lubicon Lake Cree sign historic land claim settlement.” Rabble, November 16, 2018. https://rabble.ca/indigenous/lubicon-lake-cree-come-cold/.

“Maisara Baroud Exhibition.” Kiyan Art. Accessed July 25, 2024. https://kiyan-art.com/portfolio-item/maisara-baroud-exhibition/.

Nazzal, Rehab. “CRITICAL ART AND CENSORSHIP: ENCOUNTER OF A PALESTINIAN-CANADIAN ARTIST.” Other Places. Accessed July 25, 2024. https://www.otherplaces.mano-ramo.ca/rehab-nazzal-critical-art-and-censorship-encounter-of-a-palestinian-canadian-artist/.

Nemiroff, Diana. “Ottawa Dispute Stresses Role of Art in Public Realm.” Canadian Art, July 3, 2014, https://canadianart.ca/features/rehab-nazzal-invisible-ottawa/.