Camille Henrot: On Climate Grief, Soft Labor, and “Mother Tongue”

Lyndsy Welgos: Camille, congratulations on your solo exhibition! First and foremost, I’m interested to talk to you about your sculpture 3,2,1 (2021), which is the centerpiece of Mother Tongue at Kestner Gesellschaft in Hanover, Germany. The bird figure in this piece is spectacular, with large Jean Arp-like breasts and a tear falling from its steely eye as it stands above a pile of trash and debris. Can you talk a little bit about the grief and extenuating circumstances that drive this piece?

Camille Henrot: Thank you. This sculpture was conceived and produced in partnership with the Art Foundry Kunstgiesserei St. Gallen in Switzerland. The waste at the bird figure’s feet is actual discarded objects and materials collected during the production of the piece at the Foundry.

I had been researching psychological and emotional responses to the climate crisis and started to think about how postpartum depression and climate grief are both crises of monumental responsibility that we are forced to bear as individuals while the failures and destruction of the patriarchal, capitalist economy go unaddressed. When you have a child, you are faced with the immense crush of responsibility that comes with bringing a new human into the world. I had been thinking about the psychological state of regression that accompanies motherhood and how, through empathy for our children, we might re-experience our own childhood traumas. I wanted to try to dismantle the expectation of the “good mother” and think about motherhood as a state in which contradictions, ambivalence, and inner conflict could arise and be acceptable.

The large bird figure is a crow mother, and the collected detritus at her feet conveys the weight of responsibility that she feels. But the waste is also her nest. The process of production is, in some ways, the subject of the piece—it seems we are always consuming, and being consumed by, our own production. The guilt of creating new life amidst a climate crisis is combined with the guilt of being an artist. The sculpture represents the ambivalence between destruction and transformation. Each transformation involves the generation of waste and the birth of something new, and it can be regenerative and painful at the same time.

I’d like to ask you about your series Wet Job, which addresses breastfeeding in all its messiness and explores the link between soft labor and the economy. One of the paintings in the Mother Tongue exhibition comes from this series. And I know new paintings and sculptures from the series were commissioned for the 2021 Liverpool Biennial as well. Minimalist artists such as Richard Serra and Carl Andre have created sculptures that explore the relationship between industrial labor and the economy. These sculptures are now considered to be landmark works within the history of modern and contemporary art. But works that explore soft labor and emotional labor have typically been excluded from the art-historical canon. Can you talk a little bit more about this series?

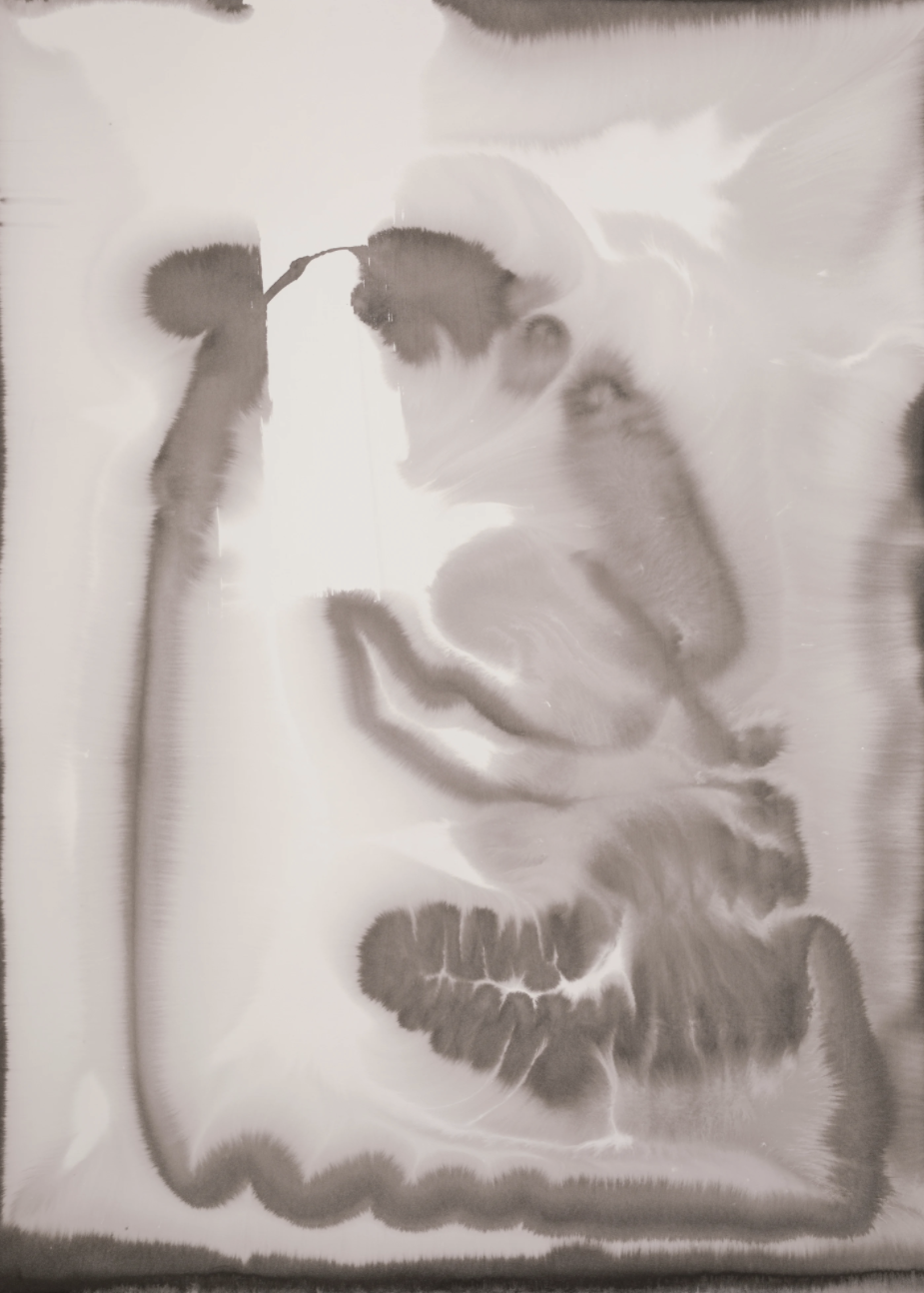

Wet Job refers to the act of breastfeeding. I became interested in how the act of breastfeeding was connected to a sort of invisible labor. The breast pump, as an object, started to carry the expectation of the woman as an endless resource who could produce at all hours of the day in any setting. But because this labor is uncompensated, taboo, and even considered illegal in certain public settings, the mother’s milk could be considered an abundance that society does not have to pay for, or even look at. While society has come to acknowledge the very real phenomenon of postpartum depression, and the mental toll that new mothers experience, I don’t think we see enough representations of the depletion and sacrifice that the body undergoes in child-bearing and child-rearing. I wanted to show the visceral and physical quality of the depleted postpartum body—the contrast between the weakened, exhausted arm that holds the child and the full, rounded flesh of the baby.

I like this expression—“soft labor.” Hard labor is an expression that is associated with work that requires muscle. Yet soft labor and emotional labor, while often psychological in nature, have direct implications on the body, too, even though they are never recognized as “hard” work. You don’t often see soft labor generating public admiration, or celebrated in classic literature and art, like hard labor is—Diego Rivera’s monumental frescoes come to mind. But what would it be like if soft labor was considered as important as economic trade, construction, and agricultural production? During the pandemic, I imagined that this type of labor would be better recognized and I even fantasized that artists could be commissioned to work within the parameters of the domestic setting.

Soft labor is also like an underground type of labor. The work of nannies, for instance, tends to go unrecognized, and they often don’t get healthcare. It’s the kind of labor that also typically falls on women of color. This adds another layer—not only do we need to attribute more value to this work, but we also need to examine the system that materially and symbolically erases nannies and their labor. Undocumented nannies are often undermined in the economy because their work is classified as an “illegal” activity, and parents often diminish the importance of nannies in the way they represent their childrens’ lives and memories. We need to decolonize the hierarchy of privilege that keeps this kind of system in place.

I’ve looked at the history of breastfeeding and it’s interesting to note that many women used to not only breastfeed their own children, but the children of other women as well. This was called “wet nursing.” It was a common practice in more rural communities where a person’s primary resource was often their own body. In An Apartment on Uranus, Paul B. Preciado wrote about this and the connection between sex work and nursing a child. Both of those activities, largely practiced by women, have been specifically targeted by authorities and even made illegal.

I am also interested in thinking about breastfeeding in relation to debt. We are all ultimately indebted to our mothers. In industrial terms, breast milk is an extractable resource that one human takes from another. In psychoanalytic terms, I have started to think that the debt that we all inherently owe our mothers might be responsible for society’s prejudice against women.

I know in the past we have spoken about the burden of responsibility that we bear toward things we cannot really control. For instance, you’ve expressed worry about how your work as an artist might negatively impact the environment: “I make a new sculpture, but it’s also producing waste,” you said. Was there a moment that really drove that concern home for you?

The pandemic really brought concerns around production and output into focus. All of a sudden all art fairs and exhibitions were cancelled or postponed and site visits were being replaced with Zoom calls and video tours. My 2020 show at Art Sonje Center was produced super successfully thanks to the flexibility of the curator Heehyun Cho. We found ways to make quick decisions over Whatsapp, and I trusted her vision. It made me think about ways that we could be successful digitally, or ways that galleries and museums in different regions could collaborate on shows so that they might reduce shipment costs and travel for artists and art workers.

The shame and guilt that comes with producing artwork—the environmental cost, et cetera—is in some ways related to the shame and guilt one might feel about bringing a new human into the world. We talked about that at the start, with 3,2,1. Having a child brings with it an awareness of how different the world you grew up in is from the one that your child is now growing up in. “Once upon a time in a place that no longer exists…”

Children’s stories always involve jungle animals—lions, tigers, rhinoceros—and the truth is that their habitat is actively being destroyed as we speak. A is for alligator. B is for bee: yet the bees are one of the most threatened species, and their decline will have a severe impact on our food production and survival as humans. C is for coelacanth: a prehistoric fish that every scientist thought was extinct 66 million years ago but was rediscovered in 1938 in the waters off the coast of South Africa. Ultimately, the scientists ended up killing the fish in order to bring it back to the museum and study it. So they deliberately caused its extinction. This illustrates how scientific research can sometimes be part of the problem, too. I was thinking about this when I made Grosse Fatigue (2013)—the activity of collecting also contributes to destruction. Original contexts or narratives become fractured, and animals are reduced to specimens. These are just a few stories that come from the ABC’s, but we could do the full alphabet with stories of other animals who are now on the brink of extinction because of the way that we as humans live.

Yet, in every way, having a child makes it more difficult to subscribe to a no-waste, more sustainable practice. You have less time, less money, and fewer choices. There is a constant conflict between individual practices and global issues, and artistic practices aren’t excluded from that.

You’ve previously mentioned an article by Meehan Crist called “Is It Ok To Have a Child.” I haven’t read that article but it sounds like it might have informed your work for Mother Tongue.

Yes, it’s a really good essay. It was shared with me by a friend and poet Jacob Bromberg when we were discussing a new film I’m working on. It’s pretty interesting because it shows how women in particular are asked to bear the burden of personal responsibility for the climate crisis. This isn’t rooted in scientific evidence: individual women don’t create more carbon emissions than men do. It’s just a PR campaign. The term “carbon footprint” was popularized by BP so that people would think that climate change had more to do with our personal choices than corporate greed and irresponsibility. As Crist argues, a student who chooses not to eat meat, who produces absolutely zero waste, is only going to make a tiny impact on the environment. It’s nothing compared to the impact that corporations make.

Of course, I think everyone who can make personal choices to reduce their contribution to carbon emissions and pollution should. But I also feel it’s wrong to ask mothers to justify their choice to have a child—the next step is eugenics. A lot of women don’t even get to choose in the first place.

Working to produce not one but multiple exhibitions in the middle of the COVID-19 pandemic must have been overwhelming, especially because you were displaced at the time. Can you talk a little bit about the other pieces in the Mother Tongue exhibition, including the paintings?

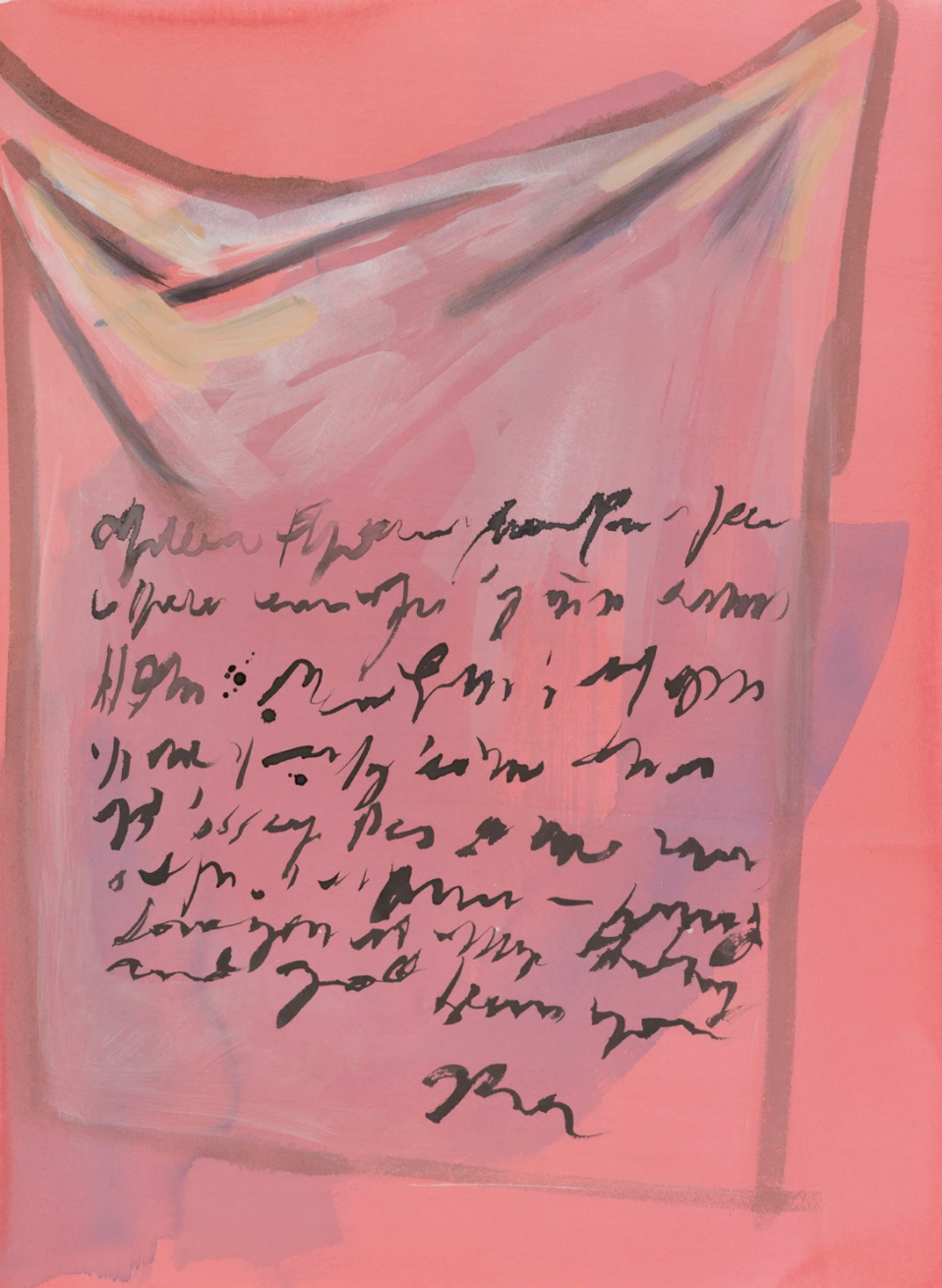

Mother Tongue is my largest show in Germany to date. Mother Tongue is the title of a drawing I had made, but it worked well for the exhibition title, too. I became interested in thinking about the birth of language, and the mouth, or tongue, as the site of both expression and consumption. In terms of the building layout, the focus is the main hall, which is kind of like the belly of the show. It features sculptures, paintings, and drawings from the series System of Attachment and Wet Job, the majority of which are new and were produced after the pandemic began. They all speak to the themes I have been exploring in the past few years—motherhood as a political category, the stages of human psychological development, the formation of language, and how our interpersonal or family dynamics are representative of larger, global concerns and issues.

There are also very small paintings from a series titled Is Today Tomorrow. I started to work on a smaller square format for practical reasons when I first left New York City at the start of the pandemic. I would work on them at the kitchen table or on the living room floor. They became kind of diaristic—I would make quick impressions with the paint that was left over from that day. All together, they look like Instagram posts because they are square, but the characters are a bit messy and dissolved, angry and full-of-rage. There’s disorder of all sorts. All of the works have the word “day” in them—Training Day, Lockdown Day, The Day we Met, Two in One day, Ruin my Day, On My Mind all Day. Our concept of time was totally disrupted and disordered because of the pandemic and the title of the series, Is Today Tomorrow, came from that feeling.

Do you find it liberating—this shift toward a more meticulous style of painting?

It is very different. In drawing, the quality of the line comes from how fast a work is executed and how easily I can repeat the gesture. It requires a combination of concentration and relaxation. It’s a bit of a sport, because it takes both physical and mental effort. I think it’s been difficult for me to take this approach with painting, because the process is usually much slower. It’s harder to work slowly and maintain a level of concentration and focus at the same time.

Painting on really small formats was liberating because I didn’t feel intimidated by the scale and the medium. The main reason why I prefer drawing over painting is because the paper takes up less space and the gesture is usually quickly accomplished. Painting requires more anticipation and planning. I felt that I could have somewhat of the same freedom and casual approach with this small format as I have with drawing on paper.

You feel like the slowness of painting was an obstacle for you?

It was and still is an obstacle for me. Acrylic and oil are heavy mediums with dense particles—they have a weight that water-based pigments don’t have. But I’ve been experimenting with different solutions, like using calligraphy brushes, which are ordinarily used for lighter mediums. I’ve been making my own paint. I’ve also been layering mediums—watercolor, acrylic, and oil—especially in the series System of Attachment, which I started in 2019. Adding and removing is also part of the strategy.

My frustration with the medium of painting gave birth to new gestures: I started to use my hands to drip the paint. In a way, the activity became more violent in terms of gesture. I would say that the viscosity of the paint also opened the door to representations that were more violent—the heavier medium is more fleshy and bloody, in a way. I was reading Diane Wakowski’s collection of poems, Inside the Blood Factory, and at one point I was painting all-red backgrounds, and my studio itself started to look a little bit like a blood factory. I really like this phrase—it refers to both the body and the process, and place, of body-making.

I’m curious to hear more about your process. Why not just paint watercolor on canvas—why do you think you need a different medium of paint?

Technically, yes, you can paint watercolor on canvas. But it doesn’t really allow me to create the diluted, liquified effect that I want. Watercolor on paper can be very striking, but on canvas, the color is much more pale. So I need to use acrylic and oil to add in other textures. I like to layer them together—I’ll create a colored background in watercolor, and then I will add the figure in acrylic or oil. Layering watercolor on paper doesn’t work too well—after three layers, the color turns brownish. And on canvas, layering with watercolor means erasing. But with oil or acrylic, you can layer the colors in an additive sense, to achieve a lighter color if you want. It’s been interesting to experiment with blending the mediums. It has been quite complicated in terms of studio organization, but I have found a lot of hope in making my own paint. It can be very pigmented, while still being very liquid. And it’s very fast to prepare in quantity.

Let’s talk about one of the smaller bronze sculptures, Celui qui a faim, which translates to The One that is Hungry. It’s one of the more disturbing pieces; I can’t stop staring at it. The sculpture is a squat figure and has what appears to be thick teeth and a dislodged tongue; it reaches out toward the viewer, and its features are fetal yet mummified. This piece stands out with a certain surreal horror. Could you talk a little bit about this piece?

This figure came as I was working on figures and shapes that you find in classical sculpture, like apples and fruit. I realized that there will always be something quite violent about food—chopping vegetables, killing animals. Along with the work on breastfeeding, I was thinking about what it means to be food for another human being. How comfortable are we, really, with this idea? You cannot really imagine breast milk being turned into cheese, or using it in your morning coffee—there is a certain level of disgust with that.

The labor of harvesting, selling, and preparing food is so devalued in our society, and food is also symbolically associated with the mother—our first source of nutrition. Being consumed, as a verb, is always somewhat pejorative or submissive. I was thinking about a lot of things when I was creating that sculpture, including the physical sensation of actual hunger. I had never before experienced hunger like I did while I was breastfeeding, and I started to think that hunger was its own person—that it had a body and a face. So the sculpture comes from that idea.

I love what you say about the mummified fetus. The appearance of mummification comes from the texture on the surface. Originally it was very smooth but it broke in some areas, so I started to work with that texture. I brushed it with a metallic brush to create wrinkles, as if it was aging like an elephant or a mummy. The teeth are also very rounded, and ultimately, unthreatening. It is kind of ageless—both old and young at the same time.

The figure lies on a little bedside table with a little drawer. It’s a detail you only really notice when you see the sculpture in person. To me, the drawer is a confirmation that the sculpture has something to contain—the way the stomach contains food or the belly contains a child. Our bodies are constantly being filled and emptied. Something comes in, and something goes out.

You are working with Antje Stahl on a new weekly, multi-chapter column for Republik magazine focused on the topic of birth, and how old Western myths, legends, and religion still have a stronghold on how we think about birth, creation, and female self-sacrifice. In your first chapter, you wrote, “Creation and procreation are still being mystified as quasi-divine manifestations located in the secrecy of ateliers, bedrooms, and hospitals. In the western culture, the artistic genius and the Virgin Mary remain two lonely figures, as archetypes they continue to influence the way we perceive artistic, sexual, and domestic life.” Can you talk a little bit about how these stories and legends still have an undue influence on contemporary art? As a mother myself, I have always hated the myth about birth being quasi-divine.

Yes, I’m very happy with the column and my collaboration with Antje Stahl. It seems both important and dangerous to write on this topic. The first chapter is called “(Pro)creation and its myths,” the second is “The Bird Mother,” which is about the “good mother”/“bad mother” binary and ecological guilt, and the third chapter “Echo Verse” is about sonograms, music, and image-making in wet environments. The upcoming chapter, “Please Don’t Touch,” relates to sculpture and tactility. When Antje invited me, I was at first intimidated because I don’t often publish my writing. But it felt necessary.

There’s a vast amount of beautiful literature and scholarly writing about motherhood, early childhood, and creativity—from Moyra Davey, Adrienne Rich, Ursula Le Guin, Annie Erneaux, Hélène Cixous, Jacqueline Rose, Julia Kristeva, Catherine Clément, and Chantal Chawaf, to Melanie Klein, Roland Barthes, Jules Michelet, Carl Jung, and Françoise Dolto. But within popular media, these things are consistently described or spoken about with ignorance and prejudice.

Like you, I was never able to relate to most representations of mothers in art, both before and after having a child. The fact that death is completely erased from the experience of birth is maybe the first signal that the archetype of motherhood is a man-made construction. Stillborn babies, genetic malformations, abortions, maternal death, miscarriage, and infertility are all inextricable aspects of the experience of parenting or the desire to be a parent, so much so that most doctors treat these things as a banality. But the rest of society acts as if these things don’t exist, or acts as if they always happen to someone else. We see this in the way economic labor is structured – for instance, women are usually not given paid leave after miscarriages and abortions. And in the arts, with a few exceptions, the splashy, bloody, smelly, shitty messiness and violence of birth is still mostly unrepresented. The postpartum body is largely unrepresented as well, except for in the amazing paintings of Alice Neel.

In the past two years, I had such a strong feeling of revolt against what is expected of women when they give birth that it was actually hard to see and accept myself as a woman. When I started to work on System of Attachment and Wet Job, it was so difficult to have the work be properly discussed outside of the clichés, or outside of my own biography. I decided for a while that I needed to banish the word “mother” from the whole conversation. I started to think that we needed a whole new vocabulary—not just images and objects.

New technology makes it seem as if our society is “contemporary,” but the values of our culture are still bathing in archetypes, in superstitious waters that cascade from centuries of patriarchal and religious inheritance. The Virgin Mary figure used to serve multiple purposes. For instance, Christian missionaries presented the Virgin Mary to Greek, Celtic, and Roman societies as a substitute for the goddesses of their pagan religions so that they would be more willing to convert to Christianity. In the process, birth and procreation became divorced from sexuality. This in turn forced women into motherhood if they wanted respect and admiration from society at large.

I’m from the region of Brittany in France, and my grandmother was a professional storyteller when I was growing up. She was very attached to Breton folklore, and though she sometimes rejected religion, she was spiritual in her own way. She would not pray to the Virgin Mary but rather to St. Anne, Mary’s mother. The reason for this was that a long time ago, missionaries who came to Brittany invented the idea that St. Anne was born in Brittany, in the city of Auray, where my grandmother was also born. This was a sort of micro-targeted strategy to convince the Breton people to give up their long-held, local, protected pre-Christian beliefs.

It’s a funny anecdote, but it illustrates the resilience of old narratives, of mythological figures, and our attachment to them—as well as the immense power of fiction and storytelling to influence cultural norms. With new images, new iconography, and new stories, we can both acknowledge that identities are constantly in flux, and build a culture that is more accepting of complexity, ambivalence, and multiplicity.

Currently on view: Mother Tongue, Kestner Gesellschaft, Hannover, Germany (April 18–August 8, 2021)

Lyndsy Welgos is the founder and director of Topical Cream 501c3.