Accessibility in the Age of Technology @ Open Score

Last Saturday afternoon in the dimly lit room of the New Museum’s basement-level theater, writer and artist Hannah Black live-tweeted a string of thoughts on or related to the dissemination of memes and Blackness.

The tweets were projected onto a large screen behind Black and a row of her fellow panelists, as audience members watched her hunched over her phone typing brisk 140-character reflections. The entire event was simultaneously live-streamed online, making it a happening of multidimensional proportions. We were all gathered after much anticipation for the second annual installation of Open Score, a symposium on art and technology organized by the digital art organization Rhizome, the New Museum affiliate.

The day-long symposium was broken into three different panels, the first of which was moderated by Rhizome Assistant Curator Aria Dean, who was joined by five other artists and writers: Manuel Arturo Abreu, Hannah Black, Devin Kenny, and Mendi + Keith Obadike. After each of the panelists gave their one-minute introductions, ranging from Black’s live tweeting performance to Abreu’s poetry reading, Dean structured the conversation around the idea of memes as a creative product of Blackness, pointing out the ways in which the content of a meme, whether it be overtly Black (see: #ThanksgivingWithBlackFamilies) or some pseudo-raceless Spongebob or Arthur still, is a reflection of how we choose to engage with race in our online conversations. She explained how memes serve as a point of relation or non-relation for different digitally-mediated communities.

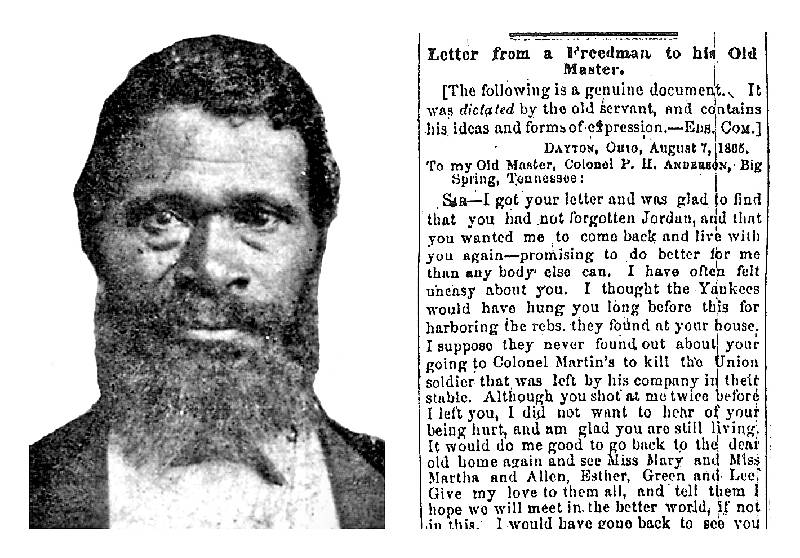

Of particular interest was a conversation about the history of the dissemination of Black culture by or from Black people. Keith + Mendi Obadike spoke directly of the correlation between memes and Blues music, noting that both provoke questions of authorship, asking who is credited, and what is our accountability to Black cultural labor. At one point Keith + Mendi Obadike pointed to Jordan Anderson, a freed slave known for his 1865 letter to his former master after being asked by said master if he would return to the plantation from which he was once freed. Keith called this letter and the image of Anderson attached to it an “early Bluesy Meme.” The conversation moved from questions of authorship to a discussion about agency, explaining that locating agency is complicated in the context of cultural appropriation and the vulnerability of expression that comes with it. Abreu noted: “If there weren’t violence against Black bodies we would share our Blackness without restraint.” The artist and poet questioned, “where can you locate agency in memes?” They argued that agency would be compromised as long as violence persisted and suggested there be “a media blackout until Black lives actually mattered.” This comment garnered an appropriate albeit somewhat nervous giggle from the audience, and spoke to the many contradictions and questions that arose throughout the day about communities, engagement, and accessibility: Should we engage? Should we have these conversations in the public sphere? And how should we do so?

The following panel considered how Artificial Intelligence (AI) technologies hold up a mirror to our current moral and political shortcomings and how technology might engage in these conversations itself. The panel, moderated by Rhizome contributing editor Nora Khan, brought together writer Katherine Cross and artists Patricia Reed, Sondra Perry, and Ian Cheng to discuss the overt gendering of AI and the possibility of AI becoming a moral educator. Cross pointed out the relationship between the conscious gendering of AI systems as female and society’s perception of the “ideal servant.” The increasing normativity of these female AI systems has direct effects on how we engage with actual people working in service, and vice versa. Cross noted the unprecedented amount of sexual harassment toward women working in the restaurant industry as being linked to the frequency with which Siri gets asked her bra size. Perry expanded the conversation to ask, “What are our ethics around the people we wish would labor for free?” Perry explained her desire to disrupt the function of these personal assistant technologies and the necessity of establishing consequences for oppressive interpersonal programming either within the world of AI or toward the individual.

After a few hours of primarily philosophical conversations about technology and its social effects, the last panel was grounded in the real-world application of these technologies. The panel evaluated the successes and failures that digital mediums have had in generating community spaces. Artist and speaker Elizabeth Mputu attempted to break the barrier between the audience and the panelists on stage by asking the entire room to join her in a simultaneous “hum.” The room buzzed for a brief moment of diaphragmatic reverence before the many audience members receded back to the quiet disposition they had maintained before. For this panel, moderator Grace Dunham framed the conversation with writer Christopher Glazek and artists Mputu, Christopher Kulendran Thomas, and Jamal T. Lewis around the idea of isolation within an increasingly interconnected online society. Dunham expanded on the ways in which digital tools work to combat isolation as well as preserve it. Discussions about Mputu’s Facebook-hosted community page “Teach Me Tease Me,” a platform for sex positivity, and Thomas’s subscription-based globalized housing plan “New Elam” ensued. At one point Dunham asked the audience members to raise their hands if they had been a part of “Teach Me Tease Me,” inviting a sense of audience participation that again fell short of true engagement. Even still, as the conversation opened up for questions from the onlookers, the presence that Mputu had expressed earlier of feeling awkward in her stature at the center of a table, spotlight blaring as she sat before a sea of staring eyes, now felt increasingly amplified. She took a question from an audience member who reflected on their own experience with the Facebook group, and for a moment it felt as though the barrier had been broken. After a brief discussion, Mputu replied, “find me after and we’ll talk some more.”

In its entirety, however, the lack of engagement from the audience members, or from the many online viewers who were tapped into the event’s live stream, loomed over the day, coating many of the conversations in a somewhat false allure of accessibility. Although it is within the nature of a panel discussion to bridge the gap between the disengaged experience of a single-person lecture and the immersive back-and-forth of a seminar, I couldn’t shake the feeling that the symposium this was merely scratching the surface of the possibilities around these much-needed conversations.

A moment early on in the day brought this issue to light. After the first panel commenced, I sat in my seat jotting down some notes from the last few moments of the discussion. A young woman sitting one seat over leaned into me to ask what I thought of the talk. I explained to her my deep appreciation for the event and for the exposure of these much-needed conversations, to which she responded, “To be honest, I didn’t understand much of it at all.” We went on to discuss more personally some of the talking points throughout the panel, and as the lights dimmed in preparation for the next round, she explained that as a young woman of color herself, social media platforms and technology have provided a means to explore the city and to be exposed to events such as this one. We both wondered how many people in the audience or at home watching were, like herself, personally engaged with the issues brought up in the talk but in need of a more participatory conversation about these critiques.

The symposium provided a refreshing examination of how technology engages with marginalized and underrepresented communities both on and offline. Questions of appropriative exploitation, ownership, community engagement, isolation, and the moral obligations of technological advancements are all too often exempt from our discussions about technology; even less frequently do we engage in these conversations with people of color, Black people, women, or trans people. The Open Score symposium provided a unique opportunity to blow open the parameters of critical thinking around these issues, but it became clear to me that there is still much work to be done in the way of accessibility.

Yelena Keller is a New York-based contributing writer for Topical Cream from Oakland, California.