A Synthesis of Intuitions: Adrian Piper at MoMA

Roughly fifteen years ago, in a summer show at MoMA PS1, designed to be a Wunderkammer, I encountered a very cool painting by Adrian Piper. As I recall, it had a mostly purple background, bright and slightly washy, with a golden phoenix-like character flying across this rendered purple expanse. At that point, I was familiar with some of Piper’s work, mainly her Mythic Being character, the intimidating Food for the Spirit series, and video pieces such as Funk Lessons, as I had the good fortune of being exposed to her in a “Time-Based Art” seminar. I struggled to reconcile these conceptual, social-based pieces with the jubilant painting. They seemed so polar. I couldn’t easily situate Piper in this tiny, world-of-wonder context, and chalked the painting’s creation up simply to youth, and its presence before me to a curatorial impetus to showcase some punchy nuggets.

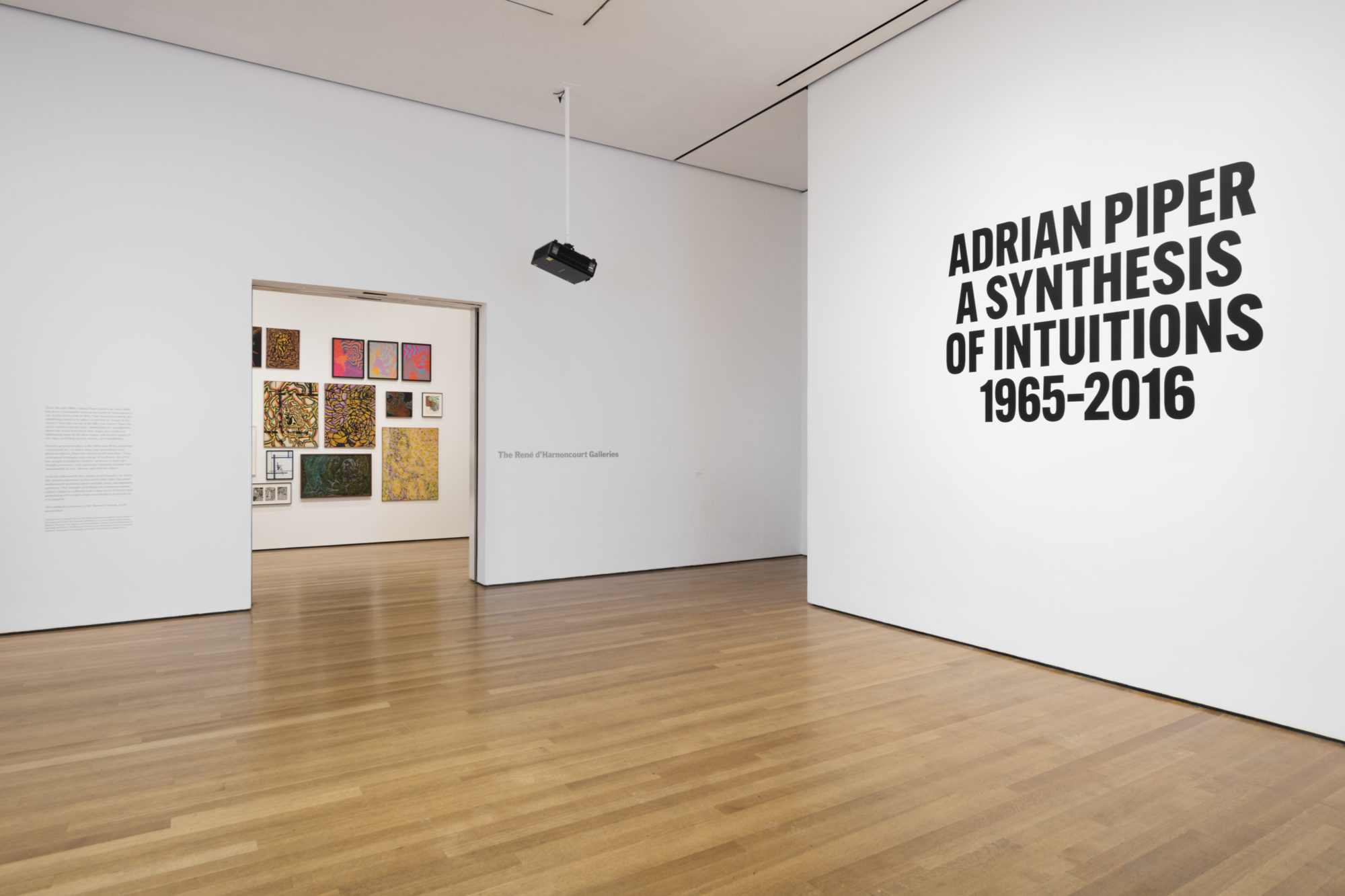

Upon entering the first room of Adrian Piper: A Synthesis of Intuitions, 1965–2016, Piper’s current retrospective at MoMA, I realized I had been mistaken. The painting I saw back in 2004 as part of PS1’s Curious Crystals of Unusual Purity was by no means a whimsical one-off. Before me on 53rd Street stood an array of paintings and drawings inspired by Piper’s six experiences with LSD: a spritely body of work, which this painting I encountered so many years ago was a part of. Piper’s LSD paintings, ranging 1965–1967, tenderly depict fractured or fracturing entities—the body of the artist, her friends, plants, bodies becoming or perhaps emerging from plants, cells in a bloodstream affected by the drug, a couple embracing—all given a variety of painterly treatments suggesting the augmentation we are familiar with as signifiers of the psychedelic—garish colors, concentric lines, micro-macro view smashing, and partially realized superimpositions.

Piper’s presentations of bodies performing states and conditions of the mind constantly evolve, responding directly to the dominant modes of communication in her surroundings by aping their form and delivery in some manner or another. Piper’s LSD paintings now revealed themselves to be a performance of her exploration of bohemia and altered states, functioning as a direct response to their environment, and prioritizing a restructuring of one’s relationship to reality. Her psychedelic works were not simply “cool,” but the outset of a practice-defining mode in which Piper employs herself as a practitioner of artistic movements or mutations. In just a few short years, Piper would begin to use both Minimalism and advertising as lenses through which to filter and interpret. Indeed, these wild paintings were in no way incongruous with the iconic works I’d learned about in school that also ask us to restructure our relationships to the coded systems that we accept as reality.

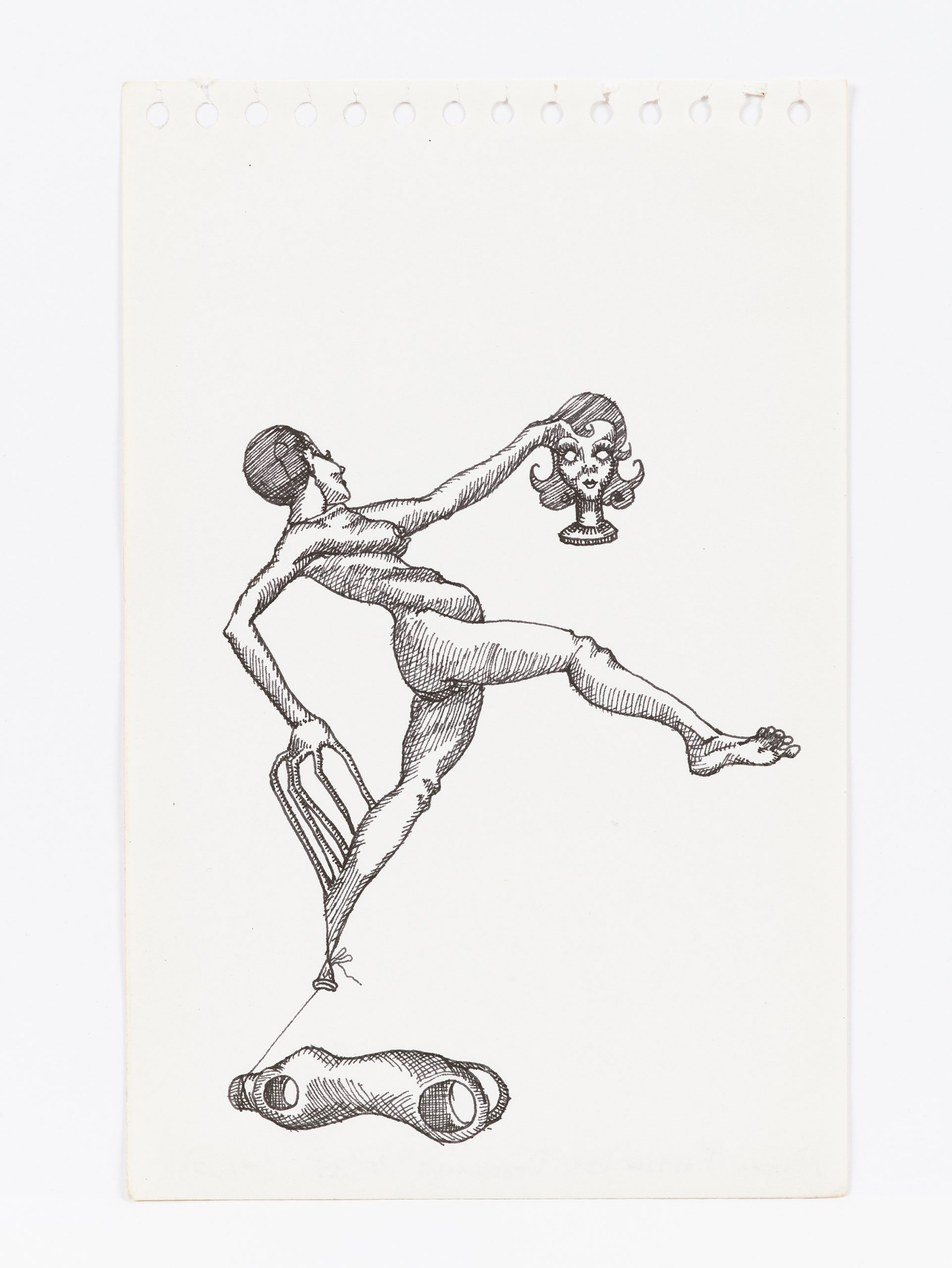

A Synthesis of Intuitions arranges Piper’s career thus-far chronologically, and unfolds in a chapter-like manner through a channel of loose rooms housing analogous projects or single-installation pieces. What emerges following the sweet preface of psychedelic paintings and gorgeously dysmorphic Rapidograph works, such as The Barbie Doll Drawings (1967), is a very palpable decisiveness and clear interest in engagement, as opposed to depiction.

Throughout the sixth floor, which, thankfully, Piper is given the entirety of, there is much to read, listen to, and watch—the sheer variety of media eschews the typical museum drone a viewer is often subjected to. This is not incidental. As Piper is responding to culture and media in real-time, she has no choice but to hopscotch formally in order to communicate effectively. In works such as The Mythic Being, Village Voice Ads (1973–75), the quintessentially American pay-to-play mode is called upon. The performance of her male alter ego, the Mythic Being, is no longer relegated to the confusing din of the street, or the rarity of a gallery wall, and enters a viewer’s personal space through the socially accepted, subversive violence of paid advertising. Shockingly and humorously, alongside advertisements for the Mime Movement Theatre Workshop and Robert Ryman exhibitions, Piper pops up as a grown man whose thought bubble shares lines from her teen journal.

Piper foregrounds her right to be heard and understood, and acknowledges this cannot be accomplished without the respectful participation of another. This acknowledgment transforms into a kind of contract through her work, (sometimes literally, via signature or hummed tune) and announces that she would like us to all help each other communicate more effectively. Embodying roles such as teacher, worker, newscaster, community member, and neighbor, she edges us toward a place of respect. For decades, Piper has maintained a notable commitment to yoga, and, throughout the exhibition, artworks foregrounding the universally inclined, cyclical energy orientation of this practice provide a comforting foil to the grotesque violence and judgment of the Western and American cultures she so incisively critiques.

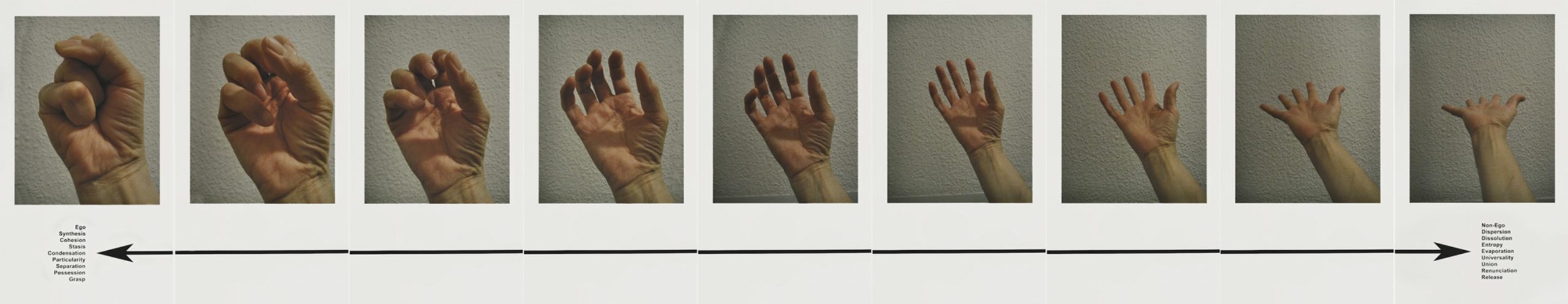

In Mokshamudra Progression (2012), Piper depicts, if read from left to right, a fist releasing—moving from closed to open—in a series of nine lithographs. Under the image of the closed fist, the words “ego synthesis cohesion stasis condensation particularity separation possession grasp” appear, and one cannot help but experience a heightened perception of nodes of tension within their own body, moments of retained pollution that can and should be exhaled. Below the open palm on the right, one reads, “non-ego dispersion dissolution entropy evaporation universality union renunciation release.” An arrow extending below these images points in both directions, a reminder that we will forever slide back and forth along this scale, but can also consciously elect to spend more time in certain parts.

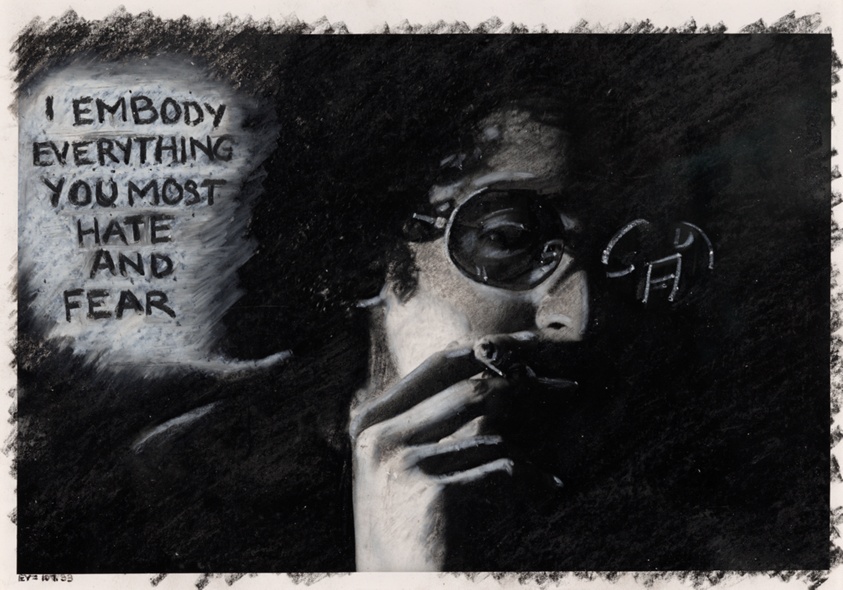

Piper does not waste any time. Her video works are set within a contemporary understanding of a viewer’s bandwidth for information consumption, and her fervent economy of means eschews a DIY sensibility, instead, offering precision with an insistence on dignity. In works such as Decide Who You Are # 21: Phantom Limbs (1992), which, as silkscreen mounted on foam-core, was likely a relatively low-cost production, she flaunts the usefulness of TLDR as a visual tactic. Piper effectively renders Mel Bochner’s syllabic paintings as quirky, linguistic decorum, by loading the form with devastating content regarding the horrific, callous insults and judgments a young black girl very likely grows up enduring in America in the 1990s.

Throughout A Synthesis of Intuitions, one experiences Piper not just as a shape-shifting character, but as herself, right down to the fingernails, as in What Will Become of Me, (1985–ongoing). The exhibit is infinitely generous, replete with black-box viewing rooms screening some of her many relevant lectures, and one comes to see what an incredible person she is. In I Am Somebody, The Body of My Friends #1-18 (1992–95), Piper inserts her imaged body into the institution, cropped diagonally from above, along with her friends (some of whom are indeed very powerful figures in contemporary art worlds). In what appear to be quite pedestrian photos, Piper sort of splashes in puddles of institutional critique, hosting transparency about her informal, personal relations with some of its most powerful agents. In doing so, she retains a sense of earnestness, and honestly, without this, the work could not offer such intense resonant frequencies.

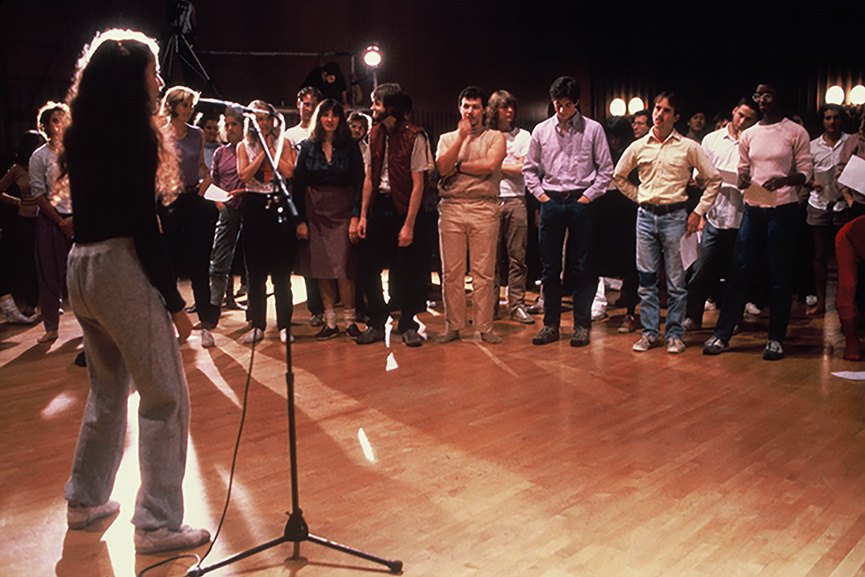

Piper’s body, and by extension, work, moves with great purpose, and often. In The Big Four Oh (1988), she performs a dance celebrating her fortieth birthday, shimmying with her back to the camera in an otherwise dismal seeming room for roughly an hour. The past weaves into her celebratory day via an old diary placed on the floor, while seemingly timeless effects of Americana and weaponized chivalry are gestured toward through the baseballs and busted knight’s suit littering the museum’s floor. Nineteen years into the future, she flows again for an hour with self-assured joy, dancing alone midday on the streets of Berlin in Adrian Moves to Berlin (2007). And, of course, in the seminal Funk Lessons (1983), she tries to teach graduate students to dance, hilariously demonstrating the awkward limits of pedagogy for movement within centuries of conditioned behaviors. All of her actions have a giving quality. We are lucky that Piper chooses to engage with us, as she is so often quite rightly ashamed of our actions and words. She has phenomenal patience for our selfishness and our blind spots, our conditioning, and, never allowing us to escape our corporeality, reminds us of our truly despicable constructs, in what feels somewhat akin to the pain of a bruise being pressed during a hug.

Whitney Claflin is an artist and writer living in Brooklyn, New York.