2021 Topical Cream Prize Winner Zenat Begum Believes Entrepreneurship is a Form of Care

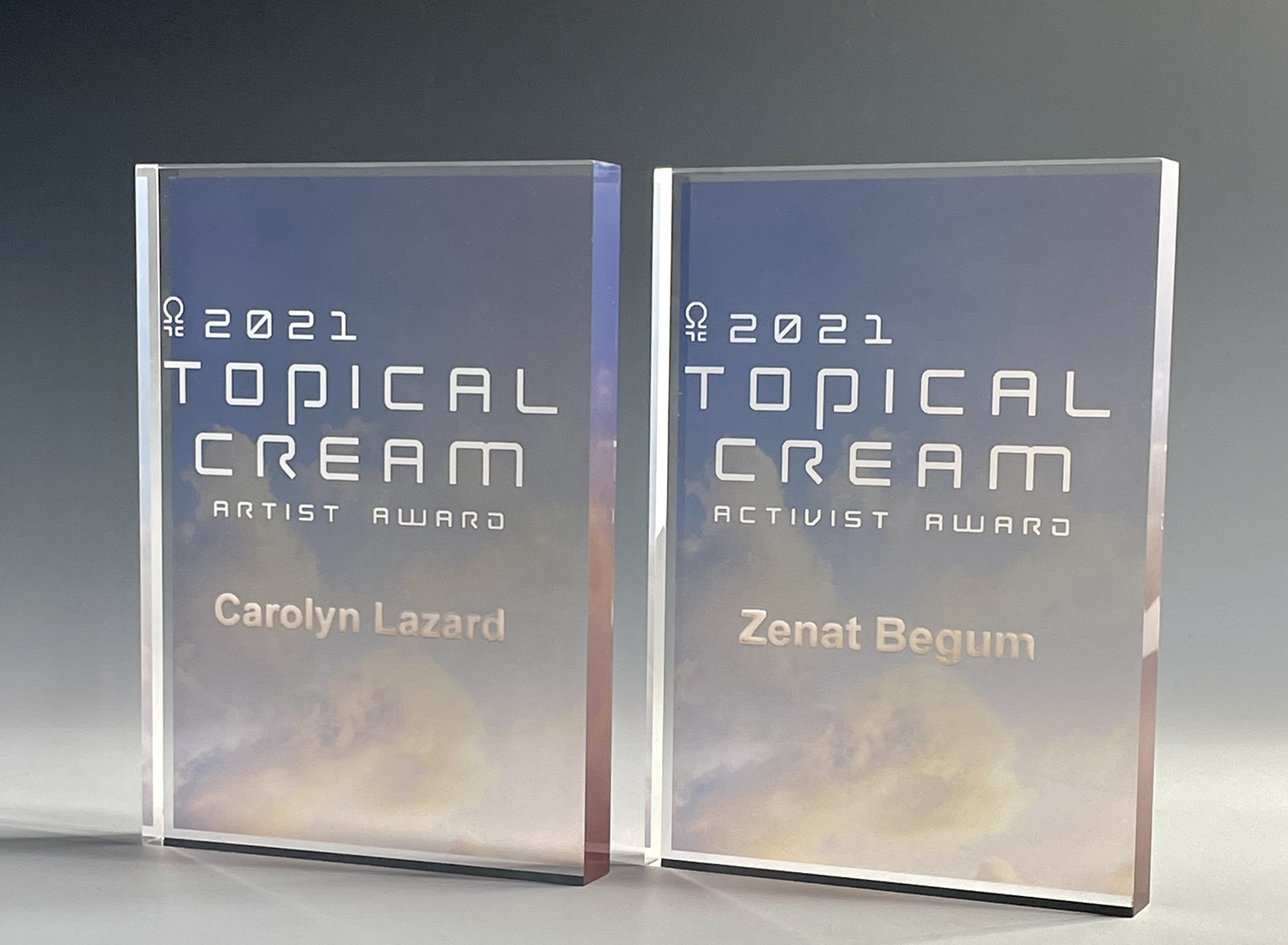

Topical Cream is pleased to announce the recipients of the 2021 Topical Cream Prize. The Topical Cream Prize is an unrestricted cash prize awarded annually to one artist and one activist whose efforts have made a meaningful impact on their community. This year’s recipient in the artist category is Carolyn Lazard, whose work is focused on the relationship between care, labor, and value. The recipient in the activist category is Zenat Begum, the founder of Playground Coffee Shop, Brooklyn.

Winners in both categories were chosen by an advisory board of leaders from the Topical Cream community that included: Lyndsy Welgos (Topical Cream Director, Prize Co-Chair), Marcella Zimmermann (VP of Cultural Counsel, Topical Cream Board, and Prize Co-Chair), Elizabeth Baribeau (Topical Cream Grants Director), Alexandra Cunningham Cameron (Cooper Hewitt Museum), Cynthia Leung (Native Agents), Rosie Motley (Someday Gallery, Topical Cream Arts Writing Mentor), Sam Pulitzer (Artist), Anna Raginskaya (Blue Rider Group, Morgan Stanley), Yulu Serao (Topical Cream Board), Seth Stolbun (Stolbun Foundation), Rachel Tashjian (GQ), Harrison Tenzer (Artist), and Elizabeth Wiet (Topical Cream Editorial & Programming Associate).

To mark the occasion, Topical Cream’s Elizabeth Wiet spoke to Begum about the award.

For Zenat Begum, entrepreneurship is a form of care. On the heels of Trump’s election in 2016, she opened Playground Coffee Shop in a Bedford-Stuyvesant storefront that had previously been a hardware store operated by her parents. The forces of gentrification had already begun to displace the neighborhood’s long-time residents and businesses, and Playground became Begum’s earnest endeavor to serve the needs of the Bed-Stuy community that had been such an integral part of her life when she was growing up. Elsewhere, she has described her business model as being a bit “Robin Hood-ish,” as she uses the money she makes selling coffee and snacks to cafe-goers to support the essentials drives, greenhouse, and free food fridges that she’s developed via Playground’s non-profit wing. This mutual aid work is what Begum is now best known for.

“Mutual aid” has become a bit of a buzzword during the COVID-19 era, as institutions and individuals have had to re-evaluate their commitments to the wider world around them. And Playground has received much attention for how deftly it’s responded to the particular forms of precarity that the pandemic has intensified. But when we spoke, Begum was quick to note that the success of her 2020 initiatives would not have been possible without the work she had already been doing with, and for, her community. Inspired by the after-school arts programs that were so central to Begum’s childhood and adolescence, even the aesthetic of Playground is meant to make the coffee shop feel lived-in, as if it has always been there.

In our conversation, we talked about Begum’s initial reasons for opening Playground, what she learned from her parents, the behind-the-scenes work of non-profit building, and the relationship between art and mutual aid.

Elizabeth Wiet: You were born and raised in Brooklyn, and Playground occupies a Bed-Stuy storefront that used to be your parents’ hardware store. How did you first arrive at the decision to transform the space into a coffee shop?

Zenat Begum: My answer to that question has changed a lot as I’ve gotten older, and my relationship to who I was when I first started Playground has evolved. I come from a very strong Bangladeshi family that immigrated to the United States for the American dream. When I went to college at the New School, I studied things that I thought would appease my parents. But after I graduated, I struggled to find a job, because I realized that for what I actually wanted to do, I wasn’t qualified. My dad had also liquidated his business in 2015, right around the time I graduated. I was distraught, watching him lose his business at the same time that I was trying to create a career for myself. I was young enough to venture off and explore my interests, but for my dad, it felt like the end of his entrepreneurship. I didn’t want to let go of this physical space—I was fearful of what the neighborhood was going to look like as it continued to gentrify. This was my childhood home, and I spent so much time here.

At the same time, I also went to high school on the Upper East Side on a scholarship. To be POC or Black on the Upper East Side is a huge contradiction of what exists there. But my friends and I would go to this coffee shop in the neighborhood called Gotham, which was owned by a Guyanese woman. This place gave us so much—the forty-five minutes we spent there prior to homeroom were everything. With Playground, I wanted to mirror the experience of peace I felt at Gotham, and at the cafes I would visit when I studied abroad in Amsterdam. I thought: “What if I tried to recreate the sense of freedom that I felt in these other cafes right here in my hometown of Brooklyn?”

I called it Playground because the space was a literal playground for me and my sisters growing up—we would run around the store as my dad would try to make sales, with screws, and tools, and trucks everywhere. We started to do DIY shows and classes. We actually opened around the time of Trump’s election in 2016. At the time I thought, “what can I do with Playground to actually benefit my community?” We held a big town hall meeting right after the election—I think over one-hundred people showed up. And I realized the power that space had to be able to hold this level of conversation among strangers. That town hall set the precedent for what Playground is now.

On the surface, hardware stores and coffee shops seem like very different kinds of businesses. Yet the purpose of a hardware store is to provide tools and supplies for people to build and maintain their homes. And much of what you’re trying to do with Playground is to create a space for longtime Bed-Stuy residents who are seeing their neighborhood rapidly transformed due to gentrification. So there seems to me to be a through-line from what your father was doing with the hardware store to what you’re doing with the coffee shop: both enterprises are about maintaining homes, and communities, in very concrete ways. You said that starting the coffee shop was, in a way, an exercise in freedom. But I’d be curious to hear if there are also ways in which you might think of yourself as continuing the legacy of your parents’ business. Are there things you learned from them that you bring into your work with Playground?

One thing I learned from my parents is motivation and drive. I’ve seen them lose their home and business, but family, and their desire to provide for us, always kept them going. I also didn’t have a lot of things growing up, but a lot of the resources I did have were the result of free programs—music was an important thing for me as a child, and I played the clarinet for ten years. I had to make the best of my situation, knowing that I might have to spend summers in the hardware store rather than at camp. I still learned how to jump rope, sing, and run on that block in Bed-Stuy. I also went to great lengths to do the things that I wanted to do. I grew up in a very traditional and strict Muslim household, so a lot of my free time was spent in my room. Playground is the legacy of my parents’ values of motivation and hard work—but it’s also the legacy of all the things that I had to actively pursue on my own while I was growing up, whether in the form of free music programs or just time spent alone and with friends, outside of my parents’ purview.

My parents really wanted me to be by the book, to become a lawyer or doctor or whatever. It’s funny that they ended up propelling me to a career similar to theirs, because it’s something they were fighting really hard for me not to do. Owning a small business involves so much hardship. There’s no passive income. I’ve worked every day for the past five years just to make sure I can support myself. But, fast forward five years, and Playground is still here after a pandemic. So I think my parents finally understand that this is something that I really want, and that I’m very similar to them in how I go about it. In the same way that they were strong in amplifying what they wanted for me, I was strong in advocating for myself and what I wanted.

One thing that’s so impressive about Playground is the real nimbleness you’ve shown in the way you respond to the evolving needs of the community you serve. During the Black Lives Matter protests last summer, you assembled supply kits for protestors. You’ve also established a community fridge initiative to provide free produce to residents, organized meal pop-ups and essentials drives, and created a greenhouse on the street outside of the coffee shop. This is but a brief snapshot of all the work you’ve done.

In media, we love to laud organizations, artists, and businesses who have somehow managed to thrive and grow in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic—I think part of that is borne from the natural human desire to find models of persistence. We want to believe that, “OK, we can get through this, there’s some hope.” Yet, I think in telling these stories of pandemic thriving, we often end up underplaying the incredible, often grueling labor that is involved in this kind of work. Many New Yorkers are familiar with your public-facing initiatives. But is there anything you might want to say about what we don’t see—about the day-to-day, behind-the-scenes work of activism and non-profit building?

I’ve had the same team for the past three years—a lot of people have been with me since the beginning. It might appear like these initiatives have popped up out of nowhere, but my friends and I were doing mutual aid, essentials drives, and pop-ups long before COVID. I had a fully free and accessible radio station before COVID. I also have a volunteer team of over two-hundred people.

I do think that the pandemic has made a lot of people realize that our previous models for success were unsustainable: to be successful, you had to be kind of ruthless, and ignorant and avoidant of all sorts of local and global issues. But the pandemic caused priorities to shift, and for the first time, people had the time and space to absorb everything that was happening. I didn’t have the privilege to work from home—I had to be in my store, every day. There are women who live near Playground in Bed-Stuy who are caretakers and who still had to go to work. When I say that I wanted to create something for the community, I meant it. When we started the Playground fridges, it really took over the world. Everyone was like, “How did you even think of this?” But it was so simple. I saw people, including myself, who were finding it difficult having to buy all of our meals, to make all of them, and also to go get them. The fridges and other pandemic initiatives wouldn’t have been so successful if our work wasn’t already so ingrained in our community.

When the Black Lives Matter protests started in June 2020, there were all these bundle sales, and all of these posts on social media about how to support POC creatives and businesses. But there was also a huge level of capitalism involved here, because you needed to purchase something to participate. We put the fridges and free library outside of Playground for a reason: we didn’t want people to feel like they needed to step into the shop and buy something in order to contribute. As we started to assemble the protest kits, we literally created a military, for lack of better term. We had phones that had police scanners and could document which way the traffic was flowing, so that we could meet people who needed water bottles or other support at available access points. For better or for worse, I think we needed this pandemic to happen because it actually showed the world what we needed to care about. You need to hit a wall before you can actually think about what’s next.

Since Topical Cream is an arts organization, I’d like to end by talking about the literary and artistic programs you’ve developed with Playground. In addition to operating the coffee shop, you also operate the Playground Annex, which is a bookstore that prioritizes work from Black, Brown, Indigenous, Queer, and POC authors. You also mentioned Playground Radio, an open-access platform featuring DJs, musicians, artists, and other storytellers from the community. And, through Playground Youth, you organized the Midsummer Playground Art Fair in 2018.

All of these artistic programs you’ve developed in tandem with your mutual aid initiatives. You might be familiar with Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, which places our human physiological needs for things like food and shelter at the foundation of a pyramid, and our aesthetic needs toward the top. So there’s this idea that food and shelter are what we require to survive—we prioritize those first—and the arts are something we can access after all of our other needs are met. And yet I know a lot of artists have tried to revise this hierarchy. I think, for instance, of the group Bread and Puppet Theater in Vermont, whose work since the ’60s has been very activist-focused. They share their own fresh bread at every performance, believing that art should be as basic as bread to life.

I’d love to hear you talk about how you conceive the relationship between your artistic programming and the essentials drives and other initiatives you’ve become so well-known for. How do you see the arts fitting into the other work that you do with Playground?

I love that question, because when we started doing the community fridge initiative, we were simply placing these residential fridges that people had donated to us outside the shop. They were these big bulky white appliances, super heavy, and I was like, “God, this is an eyesore. What do we do about this?” So I started inviting my friends to paint the fridges—and I invited them to paint the take-one-leave-one library, as well as the greenhouse. Free resources usually look pretty shabby and utilitarian, but they don’t have to look that way. People were confused. They were like, “Why are you working so hard to do this?” And I was like, “Well, I want people to be happy to use these resources. I want these to be a source not of pain, but joy.” When you pour energy into these things, people give the same energy back. This also gave my artist friends an opportunity to leave their own houses during the early days of the pandemic and do the things they love again—so many arts workers have been laid off or furloughed. Painting these fridges also makes it feel like they’ve been there forever. They don’t just feel like a temporary COVID thing.

Asking my friends to paint the fridges allowed me to merge our arts programming with our mutual aid initiatives. Art, as much as food, is life. When I walk down the street and I see a bare wall, I think about how I want a mural to go there, or something. I love the aesthetic of after-school programs: everything’s made of construction paper, everything’s lined up. That’s my artistic vision for Playground. I don’t ever want to have regrets about what I feel I should have done with the space, inside or outside the store.