2021 Topical Cream Prize Winner Carolyn Lazard on Care, Community, and Collaboration

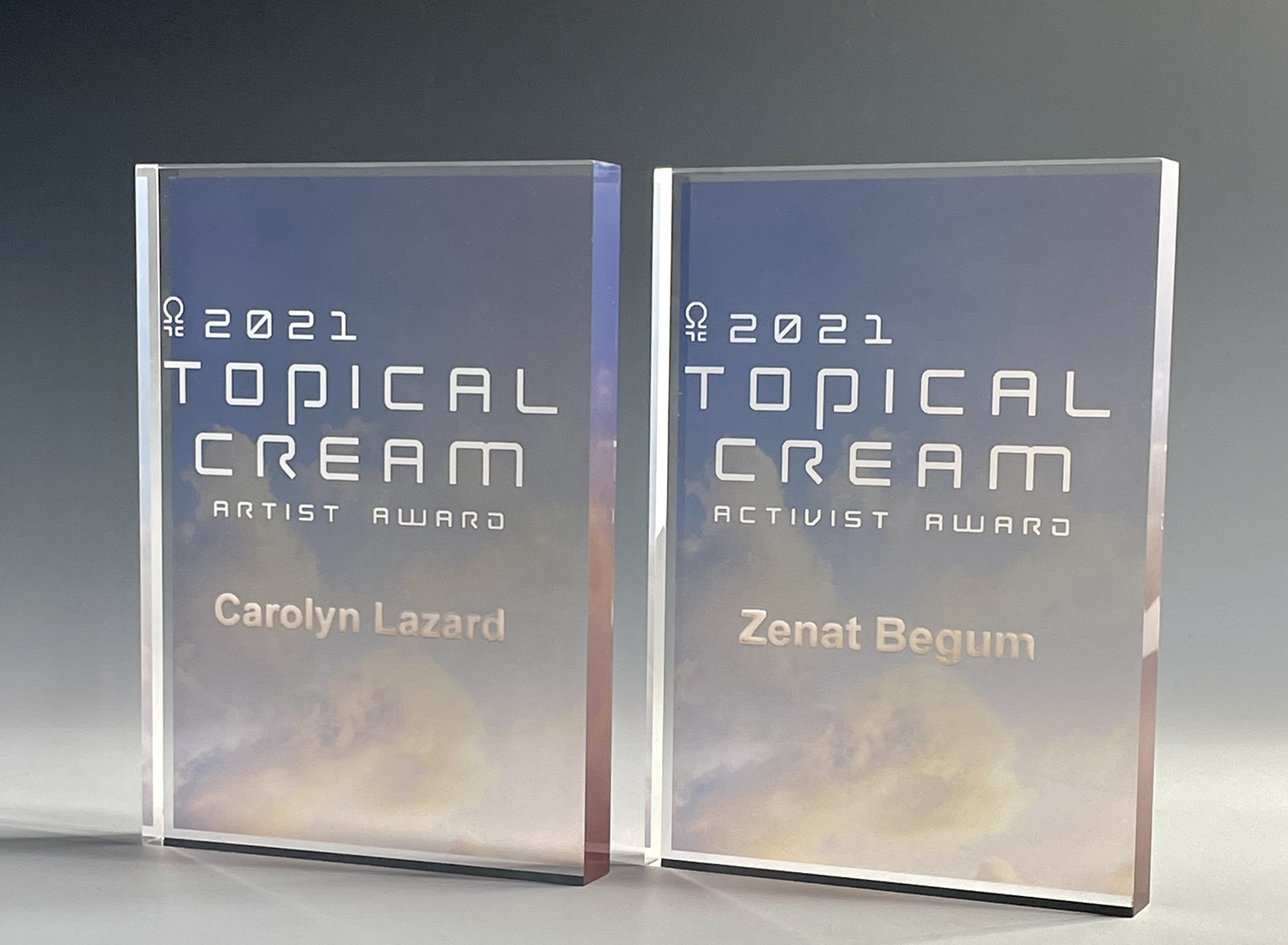

Topical Cream is pleased to announce the recipients of the 2021 Topical Cream Prize. The Topical Cream Prize is an unrestricted cash prize awarded annually to one artist and one activist whose efforts have made a meaningful impact on their community. This year’s recipient in the artist category is Carolyn Lazard, whose work is focused on the relationship between care, labor, and value. The recipient in the activist category is Zenat Begum, the founder of Playground Coffee Shop, Brooklyn.

Winners in both categories were chosen by an advisory board of leaders from the Topical Cream community that included: Lyndsy Welgos (Topical Cream Director, Prize Co-Chair), Marcella Zimmermann (VP of Cultural Counsel, Topical Cream Board, and Prize Co-Chair), Elizabeth Baribeau (Topical Cream Grants Director), Alexandra Cunningham Cameron (Cooper Hewitt Museum), Cynthia Leung (Native Agents), Rosie Motley (Someday Gallery, Topical Cream Arts Writing Mentor), Sam Pulitzer (Artist), Anna Raginskaya (Blue Rider Group, Morgan Stanley), Yulu Serao (Topical Cream Board), Seth Stolbun (Stolbun Foundation), Rachel Tashjian (GQ), Harrison Tenzer (Artist), and Elizabeth Wiet (Topical Cream Editorial & Programming Associate).

To mark the occasion, Topical Cream’s Elizabeth Wiet spoke to Lazard about the award.

Moving across video, installation, performance, sculpture, and writing, Carolyn Lazard creates artworks that interrogate the temporality of chronic illness and illuminate the forms of labor, both acknowledged and unacknowledged, that go into the maintenance of care. Slowing down our standard perceptions of time, Lazard’s durational works query the tenability of capitalism’s lightning pace and its ceaseless demand for productivity. “Instead of trying to make art about sick people, I’m trying to make art that is sick in all of its material and formal qualities,” Lazard said in a 2019 interview. But Lazard’s works are not just acts of critique: as they explore the experiences of illness and disability, they also forge new models for collectivity and being together.

Earlier this month, I spoke to Lazard about their upcoming solo show at the Walker Art Center, the importance of peer networks, their writing practice, and what it means to make art about chronic illness within time-based mediums.

Elizabeth Wiet: Often, interviews with artists tend to be very project-focused—they are usually used to promote exhibitions that are about to open, or monographs that are about to be printed. But with the Topical Cream Prize, we just want to honor everything that you’ve done over the years. So, instead of beginning by asking you “what are you working on?” I wanted to ask something a bit more capacious: “what have you been up to lately?”

Carolyn Lazard: That’s a really nice way of framing that question. I’m doing my best to take care of myself and my people as a high-risk person during a pandemic. A lot of that has required me to rethink sociality and find ways to hang out that don’t require me to potentially sacrifice my life in the interest of pretending things are “chill” or back to normal. Also, I’m working on a solo exhibition that’s going to open at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis in February 2022. It’s a big part of my life right at this moment.

Our Editor-in-Residence this year at Topical Cream, Nora N. Khan, has framed much of the writing she’s commissioned around the idea of maintenance. What does it mean for artists—whom society so often relies on to push the discourse forward—to take a step back and simply maintain during a time of incredible upheaval? Discussions about the pandemic often underscore how unique this time is, and how it’s totally separate from everything that’s happened before. But that’s not entirely the case: the pandemic has also shone a light on social concerns, inequalities, and barriers to access that are actually long-standing.

Is there anything you want to add about your show at the Walker?

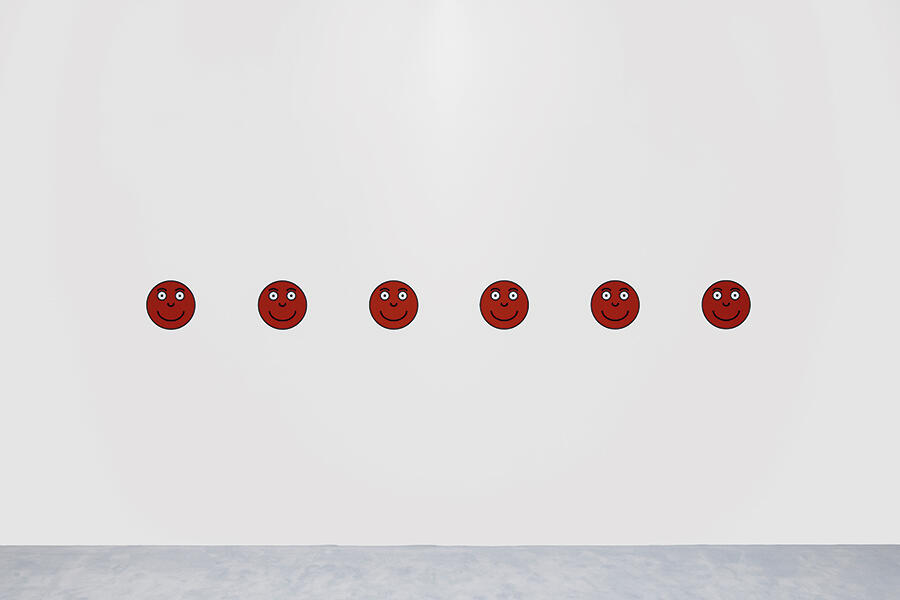

The project is a response to the historical legacy of dance films and collaborations between dancers, filmmakers, and artists, reading that through my specific lens around access. I’m trying to think through some of the claims of postmodern dance and its relationship to Black improvisation and debility. I’m basically working on a dance film that’s primarily experienced sonically. It’s been a fun collaboration with friends and artists, namely Jerron Herman, Joselia Hughes, and Kayla Hamilton.

On maintenance or maintaining, I think this moment in time is specific and particular, but not especially unique—and not discontinuous with previous conditions or the social order of things. A lot of my work is about maintenance, before, during, and after the pandemic, if we can even conceive of the pandemic as being bracketed in time. And when I say maintenance, I guess that’s just a euphemism for care or life itself.

You said you’ve been thinking about the history of dance film. That relates to something that I wanted to ask you about, which is the subject of influences and interlocutors. One name that came up repeatedly in critical appraisals of your 2020 show at Essex Street is Marcel Duchamp. There are other moments in your work that feel like subtle art-historical references: the lids of the pillboxes in CRIP TIME (2018) feel like sculptural stand-ins for the modernist grid, for instance. And yet, I sometimes find discussions about how contemporary artists “stage interventions into the history of modernism” to be a bit inaccessible—especially for those, like myself, who don’t come from typical art history backgrounds.

That said, I do find that it can be helpful to place artists in dialogue with one another in a more modest way—because it can allow us to find entry points into conversations about artists whom we might not otherwise be familiar with. When you mentioned that you’re working on a dance film without image, I was immediately reminded of Tony Cokes, who also seeks to revise hierarchies of image, language, and sound. The “Notes for the Waiting Room” (2017) publication that was placed on a side table in the installation you and Jesse Cohen created for EFA Project Space reminded me of the zine-filled Roomba that moved across the gallery in Sondra Perry’s show at The Kitchen in 2016; and your work on medical experimentation in the video Pre-Existing Condition (2019) resonates with Rodney McMillian’s recent show Body Politic (2020).

In other interviews, you’ve said that we should frame “access” as being less about clarity and transparency, and more about being together, collectivity, and care. To me, talking about how the practices of different artists relate to one another seems to model that idea of collectivity-as-accessibility. It’s not about building a canon, but about building a network. How do you think about collaboration and influence? Are there interlocutors who are important to you?

I’m in a similar position—I ended up going back to school for fine art later in life, but when I started making art I wasn’t formally trained, I hadn’t studied studio art or art history. My introduction to art, and the deepening of my investment in art, really came from being an art worker in New York. I got to know about art from working in the field. I love to occasionally nerd out on some art-historical legacies and trajectories, but my work doesn’t really live there. My hope is that my work can meet people wherever they are at, because that’s literally what my practice is about. I tend to find that the people who appreciate my work the most are those for whom the signs, symbols, and strategies I engage are immediately legible because of something in their own lives. My work is as simple as it appears.

One thing that’s challenging about being an artist is that your job is to be individuated in the public, even though you’re a person embedded in a community of people thinking together, sharing resources, and providing care. It’s hard to look at an artwork as being the concentration of one’s individual efforts, and not the efforts of so much more. My artwork is as much made from my ideas as it is made by the fabricator who made a physical object that I appropriated, or a hug from a friend, or the person who picked up my trash this morning, or the vitamin D from the sun that’s keeping me alive, or a viewer who experiences the work. Also, Tony Cokes, Rodney McMillian, and Sondra Perry are some of my favorite artists, so thanks for the citation.

In addition to your studio practice, you also maintain a significant writing practice. You’ve written essays about illness, access, and care for publications like Triple Canopy, and your video and installation works often incorporate text. As you know, Topical Cream is both a public programming platform and a digital publication—we believe strongly in writing as a tool for intervention not only in the art world, but in the world more broadly. Could you tell me about your practice as a writer, and about how you bring text and print into your video and installation work?

I don’t necessarily see writing as separate from my art practice. They operate alongside each other, and pierce each other in certain ways. Something I think a lot about is the different ways language and art succeed and fail. I use writing to do the things art can’t do, and I use art to do the things writing can’t do. Usually when I incorporate text in video work, it’s for structural reasons or for access. If there is text in the work, it’s because there’s some part of the work that requires text. I tend to not use it expressively, and save that for essays and other forms of writing.

I know I mentioned some art-historical references that I’ve felt in your work, but I’d like to take a moment to mention that works like “Notes for the Waiting Room” have also resonated with me personally. I’ve had that experience of sitting in a waiting room about to undergo some diagnostic tests, and feeling a sort of palpable, if silent, sense of community with the other patients there. Being in a waiting room can also mess with our standard perceptions of time: time can feel elongated, even if we’re only in there for a few minutes. I would love to hear you talk more about how you explore ideas of time in your work, and what it means to think about chronic illness—which has the Greek word chronos at its root—within the parameters of a time-based medium like video. Has your thinking about time evolved as your practice has evolved?

I’ve always been invested in and interested in time-based media, and in particular, moving image art that approaches duration in experimental ways. I think chronic illness also has an experimental relationship to duration, though maybe I should actually define it as being experimental and dominant since most people in the world live with some form of chronic illness. It’s just a part of being alive, but it’s also important to say that it’s a heightened condition of racial capitalism: these chrono-normative systems disproportionally affect Black and Indigenous, poor and working-class, and gender non-conforming people. Yet people always, somehow, resist them on their own terms. Standardized time is a relatively recent invention. Our understanding of time as progressive is simply not true, whether we’re looking at quantum mechanics or chronic illness.

Illness is disruptive: it changes everything around it. That disruption, depending on your subject position and your politics, can be painful, challenging, and full of grief. But that disruption can also be life-changing, and amazing, and bring you into relations of care that save you from the drudgery of a shallow, individuated, non-disabled existence. The thing that’s funny is that, yes, illness disrupts the flow of time, but also literally everyone gets sick. The fact that we even relate to it as disruptive says so much about how we are told things should go.