Female Genius: Kaari Upson

For Los Angeles-based artist Kaari Upson, the work is alive while it’s in the studio, and dead when it leaves. “I would endlessly change things if I could get my hands on them,” she says. Once an artwork is out of reach and no longer in progress, it stops breathing. Following that logic, viewers at her exhibitions confront a kind of taxidermy of relentless ideas.

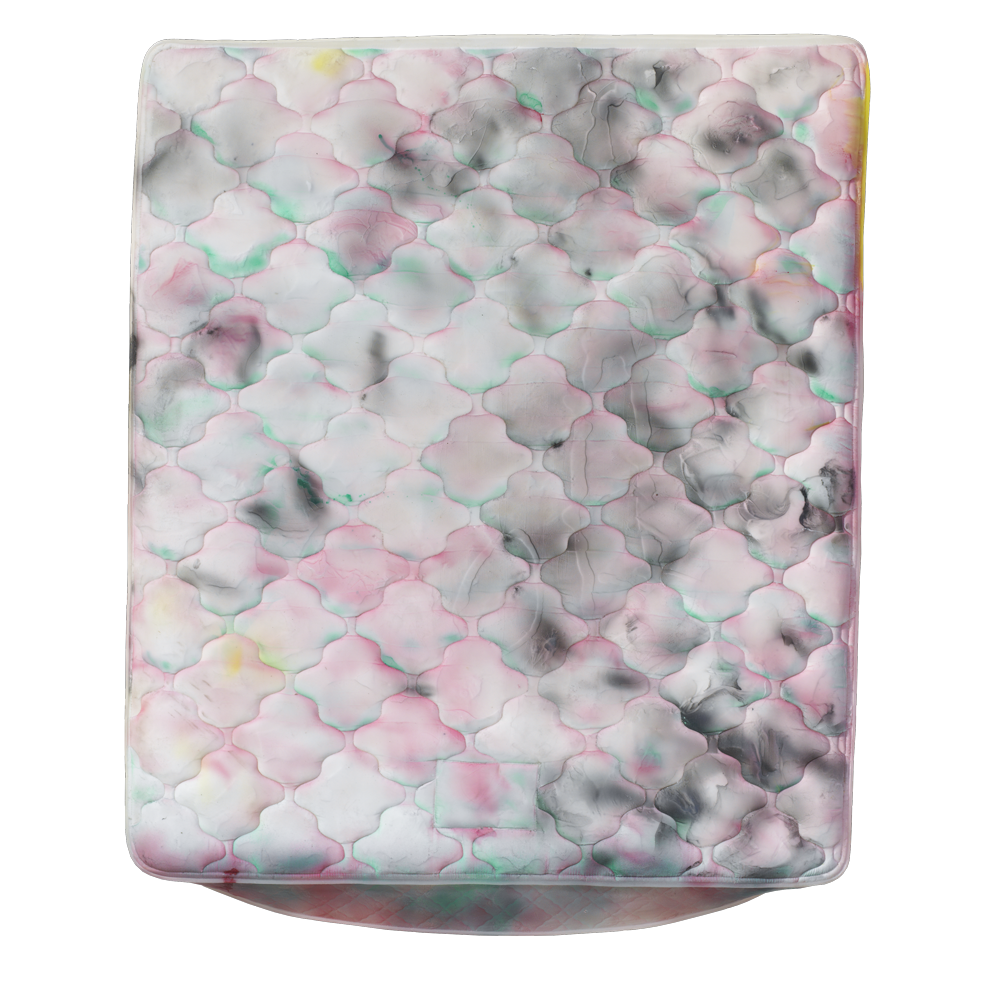

Last year, in Beijing’s Ullens Center for Contemporary Art, visitors entered The House, part of a group exhibition called The Los Angeles Project. Upson fitted The House out with furniture cast in silicone, in the last gasps of rigor mortis: contorted couches, mattresses, cushions—all objects of domesticity, yes, but she was careful about getting too literal with that metaphor. Upson is interested in the negative spaces created by objects—“the orifices, the navels, and anuses”—as well as in the chaotic psychology of the mundane. A mattress, for example, is a sponge for DNA, proof of life or otherwise. “Body and stain are always in my work,” she says.

The artist is just emerging from an enormous and acclaimed series of pieces known as The Larry Project, which she began in 2005 while she was still a student at CalArts (she graduated in 2007). The source behind it was the personal debris of a real man (Larry), left behind in an abandoned house. Upson gained access to the house, across the street from her parents’ home in San Bernardino, after it was damaged by fire. Inside, she found a trove of diaries, letters, and legal files. Upson’s response to Larry’s residue has included sculpture, installation, film, drawing, structure, destruction, insanity, obsession. “It’s funny how everyone picked up on Larry,” she says, when Larry was really just a “mirror” all along. Upson’s intention is never to create a narrative. She prefers instead to “crack the narrative open and work in the spaces between.” She says it off the cuff, as she says many things—as she says, for example, that her recurring creation of silicone mattresses might be a response to her experience of convalescing from chemotherapy. “The relationship to the couch and bed was ingrained in me.” Asked to describe the relationship, she simply says, “Hostage.”

Upson’s response to the forced immobility of illness and recovery was to make the still objects around her move. Her workspace, when it isn’t a contemplative bunker for drawing and thought, is also a film studio and a laboratory for experimental mold-making and casting. “I have no interest in mastering something and repeating myself,” she explains. “I work until I’ve figured something out or until it falls apart.” The work, therefore, is often physically exhausting and unpredictable. “If I ever come back as something in my next life, it’s going to be a Home Depot bucket,” she laughs. “I deserve it.”

Located in LA’s Koreatown, Upson’s studio is a white one-story industrial nonspace, next to a barbed-wire fence. She introduces me to her team, considers making a salad while we talk, reconsiders, puts down the spinach, pours herself a glass of water, then takes me into a more private room that has her charcoal drawings plastered from floor to ceiling. The only reason her staff has ordered take-out tamales for lunch is because Upson is busy with me—normally she cooks for the whole team. She tried opening a second studio last year, but decided “never again”: if she can’t cook for everyone at the workspace, then it’s gotten too big. Intimacy, activity—they have a way of influencing her art.

Upson is currently working on an exhibition for Las Vegas, but under a strict no-deadline policy. She said she wanted to go underground and take no interviews while she worked, “but then you start wondering why the phone’s not ringing.” Anyway, she’s comfortable talking about work-in-progress, though the forms and outcomes are still vague, and so, as a result, is our conversation. She’s okay with saying, ‘‘I don’t know yet.” That’s the thrill of it.

At one point, while filming in Vegas, Upson noticed something about her subjects. “They all had tremendous problems and none of them were in therapy.” She doesn’t elaborate further—in any case nonfiction isn’t vital for experiencing or even understanding her art—but she describes how this observation directed a new line of thought. “What if I made a therapeutic space?” What if she constructed the parallel spaces she’s so interested in to look unto themselves for healing or, rather, restoration? Well, what if? “Well, if I try to make something beautiful, it never turns out that way.”

Katya Tylevich is Editor-at-Large for Elephant, Contributing Editor for Mark, and frequent contributor to Domus, Frame, and PIN-UP. She has been published in books by Hatje Cantz, Nazraeli Press, Thames & Hudson, and others; she recently served on two juries at the International Contemporary Art Fair in Chile [Feria Ch.ACO] and was artist-in-residence at The Storefront for Art and Architecture in New York in 2013. She is co-author with Benjamin Eastham of My Life as a Work of Art, a book on contemporary art (forthcoming Laurence King, 2016). Under the pseudonym, Friend & Colleague, Katya and her brother Alexei work on editions and curated projects.

This story was co-published in PINUP Magazine Number 19. Special thanks to Eva Kenny.