Jackie Wang on “Carceral Capitalism”

Carceral Capitalism, Jackie Wang’s remarkable new book, interrogates the state’s dependency on the prison system while oscillating between the academic and the poetic. Accessible, affecting, solid, and serious, the volume covers the carceral impacts of a debt economy and juvenile sentencing policies, as well as the dystopian effects of big data and new technologies. The density of its first chapters unleashes into poems and white space, a breath, an emotion. Throughout the text, Wang conjures her position as someone personally impacted by the carceral system. The subjectivity of the poet-prisoner, a being who always already had humanity, directly aims at the figure of the superpredator myth. Wang’s own brother was sentenced to life without parole as a juvenile at the peak of this myth’s influence.

I met up with Wang on a Saturday in the middle of Manhattan. After we spoke, I walked down the crowded blocks of Manhattan and took the train, my experiences becoming more complex through the lens of Wang’s book. As I moved freely, the government was busy at work confining, detaining, and disappearing the violence through the white imagination.

LA Warman: Did this book, Carceral Capitalism, change in the course of writing it?

Jackie Wang: I decided to create a framework that would give readers footholds, so I wrote about five pillars of contemporary racial capitalism: one being automation and automated processing, the second being confinement, the third being extraction and looting, the fourth being gratuitous violence, and the last one being financial states of exception. These were different components that were helpful for me in thinking about what is happening now. I wrote the essays not knowing it would be a book. When I had the essays, I basically set out to write an introduction that would create a framework for thinking about the essays together. Part of my goal in writing the introduction was to also reconcile some debates between Afro-pessimist thinkers and people who use racial capitalism as an analytic.

After writing the introduction, I decided to write chapter one, which is about the debt economy, because I wanted to understand not only the parasitic governance side of contemporary racial capitalism, but also the private side. I wanted to think about the debt economy as a form of social control and racial management, and the disciplining of our lives and futures. I wanted to think of predatory lending as a carceral instrument.

The manuscript did change a lot. I struggled with the tone because it’s in Semiotext(e)’s Intervention Series, and they publish a lot of polemical texts that have this kind of insurrectionary bravado, but [editor] Chris Kraus said, “I actually think this tone works.” She calls it “calm and damning.”

A lot of the book is about data and secret data. What do you think is the relationship between the poetic and the data?

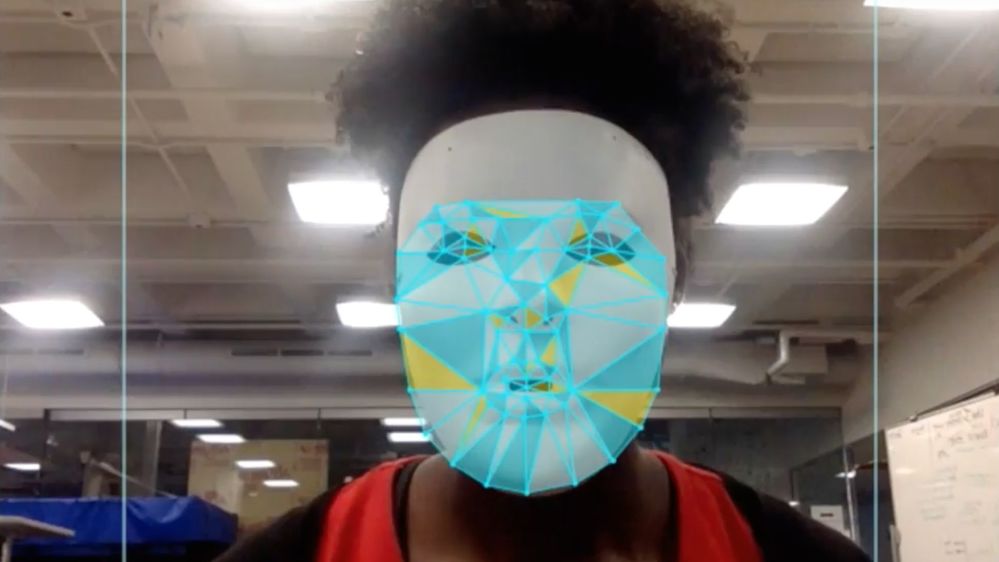

I always joke about jamming the algorithms. I would hope that is what the poetic could do. It makes me think of Fred Moten and Édouard Glissant and their ethics of opacity and the right to opacity. I know Glissant is not alive now, but his ethic of opacity is incredibly prescient. Every aspect of our lives is being subject to scrutiny, being captured, generating data: medical data, purchasing habits data, social data, exercise data, biometric data. There is like this compulsion toward total capture of our lives. In China, your typing speed and your swipe habits can be used to make credit calculations. Now there is a company that is doing social media analysis to determine credit worthiness. If you are friends with someone who has bad credit, you will be at a greater risk for being labeled as unworthy of good credit. Even in the domain of healthcare, data is being used to make predictions about us. It is taking over every aspect of our lives. I have real concerns about this, not just because the surveillance state is creepy—it just seems like it’s placing such a deep limitation on our freedom to exist, to make certain decisions about how we want to spend our time and what we want to do with our lives.

The argument of this book seems to not be something like “the moral compass of the world leans toward justice/freedom/equality.” It instead seems to be saying that those who do these wrongs will be haunted. Can you explain the role of a radical haunting?

When that comes up in the book, I’m reflecting on Mahmoud Darwish’s meditation on the paranoia produced by the prison, and the fact that the guard will always be haunted by the ghost of the prisoner, because there is a place within the guard that will register the trauma that is produced by confinement. It’s funny, because it gets into all these metaphysical questions about morality. Witnessing all of the evil in the world makes me long for the existence of a hell. [Laughs.] You know, eternal damnation for prosecutors and police. So then I’m like okay, well, even in the absence of a hell to eternally punish prosecutors, cops, bankers, etc., maybe they actually can’t run away from what they have done because of the existence of something like a conscience. Maybe stating the existence of that thing that we call a conscience is a replacement for the comfort afforded by the existence of hell to eternally punish evil people.

I think of the prison as something that haunts society. Society tries to eliminate what it wants to repress into the prison, and yet it continues to haunt. On a personal level, it is terrifying, because you have to live with all of your mistakes. But, it is its own perverted form of justice. It’s a little bit psychoanalytic, because I am in psychoanalysis, and I don’t try to claim my thinking is free from the influence of psychoanalysis.

And you thank your psychoanalyst for the framework for Carceral Capitalism!

Yes, my psychoanalyst helped me a lot with thinking about analyzing that interaction between the people that are constructing the memorial for Mike Brown and the police officers who were continually trying to erase the memorial. I can’t not read these dynamics into that interaction. There is something that the police officers must find unsettling about having that mirror held up to them, which is the memorial, which is this nagging reminder of the person who had just been murdered.

You started to talk about bodies, which I think is really interesting. In the closing chapter, it felt like you were trying to create these psychic bodies as a way to rhetorically combat police violence. I’m also always thinking of the Audre Lorde essay “Use of the Erotic” and bodies in that way. I’m wondering what you think the role of the body is in undoing carceral capitalism. You quoted Tiqqun, saying, “my orgasm surpasses devices / my joy infuriates them.” What is the role of the erotic body, or just the body, in all of this?

The Tiqqun quote, what I like about it, is it’s getting at what is irreducible about being alive, what cannot be captured by the data society. That gives me a little bit of hope, even though there is a very real—I don’t know if I would call it—goal of the data society to try to capture what is irreducible about being alive. Especially when it comes to bodies, because bodies generate data that is so valued by the big data machine. There is a way in which bodies are the new gold of our data society, in terms of what is valuable to mine. Medical experiments have been done on prisoners. Amazon is moving into the domain of healthcare and trying to capture information about our bodies: what we are eating, how much we are moving, our genetic makeup, our DNA. Ancestry.com is sharing our genetic data with law enforcement.

I can’t not think about embodiment, because the body, at the end of the day, is what is being confined by prisons and police. What is the relationship between body confinement and the mental states produced by the conditions of confinement? When you read Rosa Luxemburg’s prison letters, you can see the effects that confinement had on her consciousness. That is what Jean Genet also said he saw when he read George Jackson’s prison letters. He said that, I don’t know what the French translation of this word would be but, the letters themselves had the smell of confinement.

You talk about your brother in prison being disconnected from rapid technological change, giving one anecdote, for example, where he asks you if it costs money to send emails. You speak of the worlds in prison and outside prison as operating at different speeds.

Hopefully, I am going to write a book on carceral temporalities, a topic which connects to an essay I wrote recently about solitary confinement. The axis that is usually analyzed when thinking about prisons is the spatial axis. This is also the influence of Michel Foucault and carceral studies and the study of prisons, because there is so much emphasis on the architectural dimension of the prison and thinking about the panopticon as the paradigm for disciplinary power. I like that work, and I think it is an important axis to talk about, but I have been thinking recently about the temporal axis.

When thinking about the effects of solitary confinement on prisoners, in testimonies I have read, it fucks with people’s sense of time. Our experience of the world is, at a very deep level, tied to the temporal world that we create with people. Being embedded in a social universe gives our life a certain trajectory and enables us to experience the progression of time in a particular way. It is very terrifying to read accounts of solitary confinement because there is a total temporal breakdown. People do not know what day it is. That is also something that is manipulated by the prison administration: the use of fluorescent lights that are turned on all the time, housing people in cells that don’t have windows, so people literally become unhinged from time. That way of fucking with someone’s sense of time is actually an instrument of torture. What is the horizon of a life when you have a life without parole sentence? There is nothing you can move toward, because you have been told that you have to die in prison.

I was trying to think about the different temporalities and rhythms inside prison and outside prison as being created by technology and communication technology. The speed at which we can communicate with people is very different. When my brother wants to write to someone who is his friend at a prison he was previously housed at, he has to mail me the letter, and then I have to mail the letter to the friend, because there is no direct correspondence allowed between prisoners. That is an incredibly lengthy, drawn-out process, which is very different from us having access to instant communication with people.

What do you think about JPay, like their creation of their own iPads for prisoners to use?

I was thinking about that recently, because that is something my brother is very excited to get access to. So on the one hand, they are exploiting prisoners. You have to pay a bunch of money for content. You can’t send emails for free. It is all mediated by JPay, a private company that is profiting off of providing a communication structure for people who are incarcerated. They are incredibly evil, but at the same time, I can see that it’ll improve the quality of life for a lot of people who are in prison. My brother in the winter was like, “in February I will get my JPay iPad,” and this was something he was anticipating for months with excitement, getting to watch movies and things like that. I can see some people on the Left being like, “Oh, this is going to politically neutralize people by enabling social isolation and separating prisoners from each other, or by keeping them entertained.” I can anticipate those critiques, but I also think that, if free people have access to movies and music and instant communication, why shouldn’t prisoners? JPay iPads will change the temporality of incarceration, too. But overall, we should be critical of the way JPay profits off of incarceration, and should, when thinking about improving conditions inside prison, always keep our eyes on the horizon of abolition.

LA Warman is a poet and performer based in New York City. She is the founder of GLASS PRESS, a publisher of art and poetry on flash drives, and teaches erotica classes online and in Brooklyn.