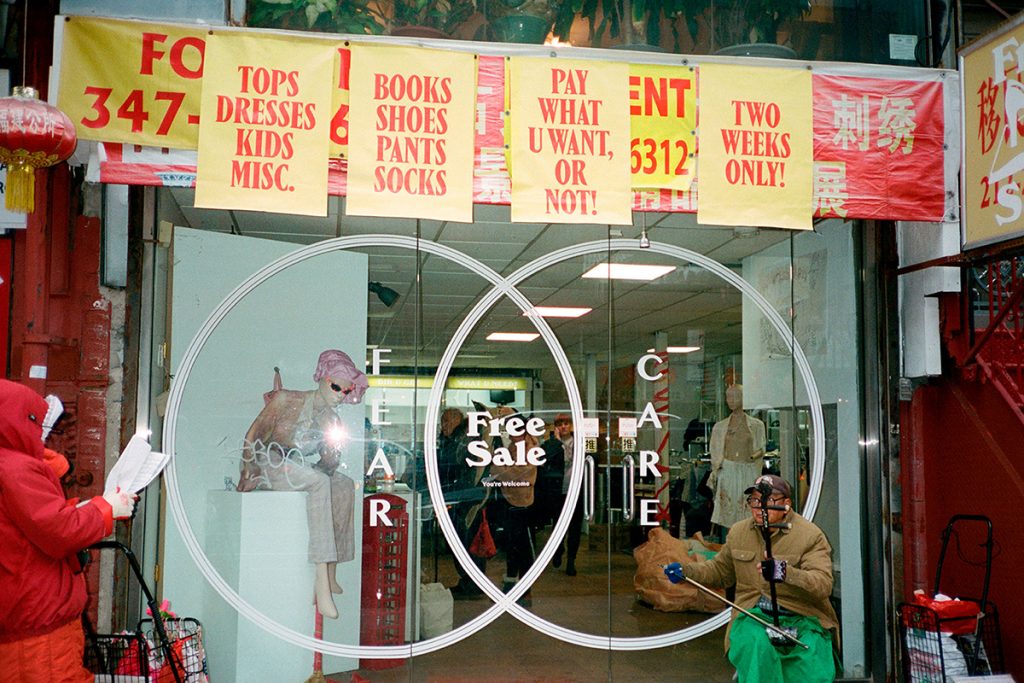

In December 2019, Topical Cream worked with Avena Gallagher to present the fourth iteration of Freesale. For this iteration, Gallagher built what could be described as a functioning ecosystem at 22 East Broadway in New York. The shop was open for the month of December and inside, every single item was free. With Red Bull Arts as a silent financial backer, we were able to build a three-level department store filled with items from Gallagher’s personal and professional archive. Freesale 2019 also included a one-night opening/closing party and art exhibition, a New Year’s Shinto ceremony, a performance by I.U.D., free daily meals from Replate, and free Red Bull energy drinks for shoppers. Topical Cream took this opportunity to connect Freesale with our nonprofit partners, Women’s Prison Association and Streetworks, whose clients were invited to a special appointment where they were given exclusive access to the store. Below, please find a poem from Gallagher about Freesale, as well as an interview between Gallagher and designer, professor, and Freesale shop volunteer Gerlan Marcel. A full list of credits for the project is provided at the end of the piece.

Freesale

A small operation that asks questions

and seeks to do an ordinary thing differently.

An act of alternative recycling

a personal excor-cise in self-healing of hoarding, A pawning-off of a (mostly) personal hoard.

A collaboration between the giver and the taker,

a kind of group therapy –

an anti-capitalistic exchange,

a political act.

A mitigation.

A new store, an interesting experience.

A pop-up. An influence.

An old wind.

A matter of transformation,

A matter-transformation.

Something dull that glimmers one day or hopefully someday.

Attraction

A magpie’s bits, sidewalk sale, sidewalk, something abandoned, something forgotten, garbage.

A key on the street.

Santa pants in the gutter.

Red gown in a trash can.

The invitation of the random.

Freesale is a small hustle, a quiet performance, a ritualized release, an emo-baptism by unclutching, surrender of an irrational armory-cum-bunker, whose bricks are lonely single socks, who once lived on better feet, in a better life, once before – awaiting a new life…

Charged bits of string from locales of untold obscurity, interesting and uninteresting old clothes, objects held hostage, phantoms of emotional protection from painful recollections or compulsive mind-programs… a vain attempt in claiming useless objects as a way to claim the

orphan within.

Collections

of

symbols

of

other things,

converter things, conduits, mascots, sentiments, human evidence, evidence of humanity. Excuses.

Money.

Piles of threads.

Old stories. Shoes someone got mugged in once.

Something from an exotic trip.

Something from a boring place.

Something stained with a song. Stained with tears.

Pockets full of packets.

Pockets of shock.

Something torn, something mended. Something dirty. Something cute. Something nobody cares about. Something you might like. A curation of curious taste.

Some stuff is haunted.

Some stuff is happy;

ready to be accepted, Harbored, Admired, enjoyed, Worn, Used, Given, eaten.

Some stuff wants you to be proud of it.

Some stuff is sorry.

Some people don’t think this much about some stuff.

Some things are people

Some things are feelings

Some things are for you or for someone or for you to take to someone.

Things conduct energy. Stuff projects emotions

Some stuff has projections. Some energy is inside things. But

It’s only stuff.

Feelings are not everything.

Feelings are not stuff.

Movement is inevitable, accumulation can be problematic, waste is a shame.

Some stuff is shame.

Letting go is good.

Giving is good.

Congestion should disperse.

Heavy is not fluid.

Cumbersome is burdensome.

Gerlan Marcel: First, I want to talk about the idea of Freesale in general: that to be free in our capitalistic system is one of the most radical acts. How did this idea come to you?

Avena Gallagher: It was really organic, I suppose. I’m a hoarder, which I inherited from my Gallagher grandparents. I’ve always accumulated stuff and always personified things, giving objects a lot of emotional meaning and importance. I remember I first had the idea when I was working with Camilla Nickerson and Rob Pruitt was doing his flea market. I had this dream of having a street stall, because I’ve always loved shopping from people on the street. I had this vision of one in a very specific place in Chinatown. I always wanted to have my stuff just be for the taking. I wanted the set-up to be rather transient, so that people could just pass through. It wouldn’t necessarily have been attended or kept by me. Somebody could have just been sitting there in a folding chair, or not. At some points, in my mind, there was a person in a chicken costume, who would serve, in my original vision, as a disruptive entity. At one point, I’m not sure how many years ago, I actually bought a chicken costume, and then it stayed with me over the years. That chicken costume ended up in this fourth iteration—my son Malcolm found it and it became his favorite thing. He’d wear it in the store. So it all came full circle.

There’s a lot of things coming full circle.

How did you end up choosing the space at 22 East Broadway? It was really special.

Lyndsy [Welgos] found it! She was like, “There’s this listing on Craigslist.” We went to go look at it through the window, and I was like, “Interesting…” All you could see was the first floor. But we eventually went to see the whole space. … It was a three- or four-level space. You can’t see this from the street, but when you walk to the back of the first floor, there are all these different stairways and different rooms. The discovery of the additional spaces, the upstairs and the downstairs, was a shock and a wild sensation. Kind of like when you have a dream about a place you know well, but then you discover a whole new place within it which did not exist before as you knew it.

It was almost like a Chinese mall.

It actually was a Chinese mall, formerly. There was the main floor. There was that little secret room off the entrance, which we turned into what we called “Malcolm’s apartment.” It had all the kids’ stuff in it. There was that room in the back, what I called the “soft room,” which was a carpeted quiet room with the surveillance feed, because we had a surveillance system.

The surveillance system was interesting. You had a live feed of the CCTV camera footage playing in the “soft room” at the same time that it was being recorded.

Yeah, we had cameras all over the store. It was kind of absurd to have security cameras in a place where everything is free. But surveillance cameras were always part of my original vision—to record the movement and the coming and going of stuff. I think that also connects back to me still being so attached to the stuff. I wanted to watch every last moment that I had with these things. It’s so stupid. … But, even though the stuff was free, people did steal.

I want a little bit of behind-the-scenes. I know bringing all this stuff out of storage was an exhaustive and emotional process for you. Tell me a little bit about how you transported stuff to the store, and what actually made it upstairs.

I had four storage units. I think it took three or four trips with a U-Haul cube truck to bring everything to the store. It was so overwhelming, honestly, having to move these four truckloads of stuff that I hadn’t seen in years. I avoid storage like the plague. And so, while I would put stuff into storage, I would never actually go to the storage units because I couldn’t handle it. I just shoved everything in storage and forgot about it.

Except for that monthly paycheck to Manhattan Mini Storage—that must have prevented you from forgetting about it completely.

Yeah. That’s tens of thousands of dollars in storage fees. It was all there, just piles and duffel bags upon duffle bags and boxes of this shit.

What was the process of sorting this “hoard,” let’s call it?

It was so scrambled that nobody could really sort it except for me. That’s because, embedded in all of that scrambled stuff were things that were so precious and dear to me, like family heirlooms: things that my late father had made when he was a child, things that I certainly shouldn’t, or wouldn’t, give away. They were all scrambled in.

Every single wide-ribbed tank.

Oh, you mean all those old threadbare t-shirts of my grandpa Gallagher.

It’s hazardous: everyone thought they were rags, but they weren’t rags.

You couldn’t distinguish them from garbage. My Gallagher grandparents were the hoarders who would not put on new clothes until the clothes they had literally disintegrated off their backs. I collected a lot of this extremely distressed clothing. Throughout the process, I would rescue things that I wasn’t quite ready to get rid of, even though I had already put them in the store. There might have been a few times where I literally snatched something out of someone’s hands.

You mean customers?

Yeah. Like, “Actually that’s not for sale.”

You must have been incredibly vigilant.

It was exhausting. I couldn’t be in every room at every point in time. That’s why, after it closed, I couldn’t look at the pictures of the store. I still kind of can’t. I couldn’t think about it. This is the first time I’m talking about 22 East Broadway Freesale since it happened.

You wrote this beautiful piece, it’s almost like a Freesale haiku. You talk about this being an anti-capitalist exchange and political act. It was definitely all those things. It was this community-based action and it was a personal exercise in self-healing from hoarding. That experience of putting yourself out there must have been a pretty emotional journey, done as a performance in front of people.

Yeah. It was a little performative, in that Freesale’s origins are very personal. The merchandise is mostly personal belongings that I am letting go of. … I do believe that hoarding is something you can inherit, and this project was both an excuse and treatment for my hoarding.

Don’t you think that’s part of the capitalistic system? This need to constantly, perpetually accumulate—it’s this self-exhaustive, depleting cycle.

Totally. If we trace this back to my grandparents, they hoarded as a response to their poverty. I feel like I’ve hoarded as a means of emotional protection. But for others, poverty is definitely mixed into it, too.

There was a sort of breaking free from emotional attachment to what you had collected.

I deliberately throw stuff into the Freesale pile that I love dearly, to make it more meaningful in a sort of elemental and energetic way. Obviously, the people who come through the store, I don’t even know. And they have no idea that they’re taking stuff that holds any emotional meaning. But it’s an energetic movement to try and send out this ripple of divesting from material. It’s a ripple of detaching from emotional bondage that I hope will be shared in any which way.

Add Image of security camera

You are definitely a storyteller. It’s something that you do beautifully, whether creatively, professionally, spiritually, or personally. But all of these objects that you have acquired also have these incredible stories. In the poem, you mentioned some specific things—maybe you’d like to share one of these stories with us? You talk about Santa pants in the gutter.

The Santa pants in the gutter is a true story. Best pants I ever had.

Right. And this time, there was a checkout in the store where you took photographs of every single piece. You have at least, like, 6,000 photos?

There was so much stuff, and it was such an active store, that I barely had time to connect. Not every piece was photographed or recorded. … It was just impossible to get everything.

ADD Image of Erica

You said in your beautiful Freesale poem that some stuff is haunted, some stuff is happy, some stuff wants you to be proud of it, some stuff is sorry. What are some memorable things you witnessed at the store?

There were so many things. One time, I was sitting there having tea or coffee while a really sweet Japanese woman was shopping. I saw her really lovingly open up this beautiful piece of hand-batiked fabric that I got in India. She was handling it with such care and regarding this beautiful piece of fabric that I didn’t realize was now in the store. I had to explain to her that that piece was really important to me. She was so sweet and understanding about it and I felt like an asshole. But she was like, “Yeah, you would miss this.”

You had a sign that was quite prominent in the main room: “Don’t be greedy.” That reminded me of the Diggers. They were hippies who had had free stores in San Francisco and New York in the late 1970s. But there were always these greedy people coming into the stores. And at the end of the day, the people who worked there would have to piece the stores back together, because it felt like a tornado went through. Did you have any interactions with people who were just greedy, who kept coming back again and again for more stuff?

Not really. I’ve got to say, every day was so touching. People were so grateful to have stuff for free—particularly the neighborhood people. There’s a lot of elderly people in Chinatown. Though at first, that community was really suspicious and confused about what I was doing.

I remember this. I had people come in and be like, “It’s free? You’re sketchy.”

Yeah. And like, who am I? I was this outsider in deepest Chinatown. But then it sort of caught on. There was one woman who would come to the store every day. She lived alone in that monolithic brick building near the Manhattan Bridge. She’d come to the store to have a pastry—maybe she’d have tea—and she’d find something to take home for herself. But it was reciprocal: she would also bring in noodles that she made for me. When we closed up the store, she was actually in tears. She hugged me, gave me her phone number, and said, “Maybe we can talk sometime.”

Living in the world that we live in now, that community experience of literally free food, free things that you need for your life—from housewares to lingerie, to socks—and then the community spirit within … all of those things seem extra utopian.

I hope.

You said in your poem, letting go is good and giving is good.

There were also plenty of people who came to the store not for the creative concept, or because art was happening, but simply because they needed things and couldn’t afford them.

Right.

For this iteration with Red Bull and Topical Cream, Red Bull found the money to fund us within their department that deals with social and community action. That was really cool. Freesale began as a rather personal project of mine—it wasn’t so articulated in terms of community or social action. So the Red Bull sponsorship resulted in an amazing perspective shift, making us more aware of how building this space was motivated by a need to do something for the community. We reached out to groups that dealt with populations who were in need, including nearby shelters and the Women’s Prison Association, who help to rehabilitate women who are just getting out of prison. We also reached out to Streetworks, a group that works with homeless teens.

I hope that people talk more about the distribution of wealth and material in this world. Because someone like Jeff Bezos has enough money to give every homeless person in America a house. These billionaires have enough money to feed everybody in the world. And yet you have a humanitarian crisis like what we have in Yemen, where something like 85,000 children have starved since 2015, because of this proxy war that the US is fighting there against Iran. But this is just one of endless examples of the ills of empire, or capitalism. Not that Freesale is exactly about that, but …. behind almost everything we buy, or have, is suffering.

We’re talking about a hoarding of wealth.

Yeah. There’s more than enough stuff for everybody. There’s enough money. We don’t have to work this hard simply to be alive. It’s grotesque.

The capitalist system wants us to constantly accumulate stuff. But over the past few months, with the closure of various stores, we’ve seen the limits of accumulation—we no longer have the same ability to keep accumulating. Many of us have been re-evaluating our own experience with stock and the ability or need to purchase.

Even debt is bought and sold by corporations and banks. Even the absence of money is sold for profit. Capitalism is a dark ass vacuum into which all of our souls are being sucked.

It’s interesting to see how people react differently to this sort of vampiric capitalism. Your answer, with Freesale, is to “sell” your possessions at no cost. And this idea of things being free is just so fucking intoxicating.

Can you talk a little bit about the Freesale art exhibition and closing party?

We found this incredible space that had various rooms that could be used in so many different ways, so we decided to turn some of the space into a gallery. I started calling around and asking friends if they wanted to be part of a group show, which would serve as both the opening and closing party for Freesale. One really important element for me was letting the store open without the engine of social media promotion or content creation.

One of the artists that I asked to be a part of the exhibition was my friend Mari [Ouchi], who has a really cool jewelry line, FAUX/real. She also does some performance stuff and she’s just a really creative, amazing person. Mari wanted to do a Shinto ceremony where you give a toast at the New Year, taking three sips of sake, each representing the past, the present, and the future. So we distributed sake to the audience and everyone took the three sips together. It was very moving. After the Shinto ceremony, the band I.U.D. played, which was fucking amazing.

I do feel lucky to have been in that basement that night. The Shinto ceremony really felt like an exorcism.

It was all very organic and spontaneous, but who knew that it would come together so well?

Gerlan Marcel is a New York City-based creative director, print designer, and graphic storyteller, working in the medium of clothes. In 2008 she founded her label Gerlan Jeans, working with Avena Gallagher as stylist and collaborator throughout the brand’s herstory. Gerlan’s clients include Kenzo Kids, Jeremy Scott, Barbie, Puma, Disney, and Arizona Iced Tea. Gerlan also teaches at Parsons School of Design in the BA Fashion Design Program.

Special Thanks

Ara Anjargolian, David Barrera, Nat Carlson, Kyla Chevrier, Aileen Cordero, Emmanuel, Erica, Joe Heffernan, Kyle Jacques, Sofia Jimenez, Julia Kim, Malcolm, Gerlan Marcel, Andy Martinez, Greg Miller, Kenta Murakami, Kristen Nichols, Jessica Ortega, Babak Radboy, Emily Sasmor, Mike Seigel, Suzanne Seigel, Yulu Serao, Meri Simonyan, Shane Smith, Stuart Stone, Jeffery Tranchell, Alix Vernet, Lyndsy Welgos, Max Wolf, Marcella Zimmermann

Special Thanks to These Organizations

Red Bull

Women’s Prison Association

Streetworks

Replate

Material for The Arts

Artists

Julien Archer

Payton Barronian

Lizzi Bougatsos

Marlous Borm

Drake Carr

Emily Sasmor

Kyla Chevrier

Susan Cianciolo

Tony Cox

Nathaniel DeLarge

DIS

Doris Guo

Sean Kierre

Josh Kline

Rosalie Knox

Paul Kopkau

Maia Ruth Lee

Maggie Lee

Marlene Marino

Gloria Maximo

Shawn Maximo

Mari Ouchi

Isabel Penzlien

Ser Serpas

Nick Sethi

Shane Smith

Analisa Teachworth

Bernadette Van Huy

Anicka Yi

Carissa Rodriguez

Performance

I.U.D.

Mari Ouchi

Photography

Lyndsy Welgos and Alix Vernet