Space All Encompassing

In her essay “Space All Encompassing,” Diana SeoHyung grapples with the complexities of how we write about those who no longer share our time and space. How might writers resist the urge to merely resuscitate through a distanced temporal lens, and instead use the precision of language to meet in the present? Bringing her own intergenerational familial relationships into dialogue with the formal and relational strategies of artists Leo Amino, Theresa Hak Kyung Cha, Jack Whitten, and Eva Hesse, SeoHyung imagines writing not as a bridge, but as a container—as a space for being with others, including those whose lives are already lived.

– Lumi Tan, 2025 EIR

Dear Mark

I love you

Mom

Earlier this year, I gave a note to my six-year-old child. A few days later, he proudly handed me a note that he wrote for me at school.

Dear Mark

I love you Mom

I had taken for granted that he knew the convention of addressing a note by using “Dear.” That he thought all notes began with “Dear Mark,” but moved up “Mom” so that it would be clear that the message is he loves me but that it is not from me—there was something profound that was touching.

Though unknowingly addressed to himself, it was still a note he wrote for the purpose of giving me. The mistake allowed me to understand that this was an explicit nod and response to my having written to him. Had he given me a note that read, “I love you Mom,” or even, “Dear Mom I love you,” it would not have been the same. We were both writing to Mark, loving him and loving me. “Dear Mark” became a container where our love for each other would meet and be together.

⁂

The narrative of Western art history is organized with the presumption of time’s linearity. Discussions of non-Western artists usually occur outside of this framework, their contributions ascribed a characteristic of submergence or exceptionalism, not seeming to take place in time. Writing about artists of Asian descent has therefore allowed me a sort of historical impunity, providing a sense of agency I rarely experienced growing up as an immigrant. While in graduate school for art criticism, I felt powerful as the room became quiet whenever I read my writing on an Asian artist unknown to my classmates.

Because of my track record of writing about the art of Asia and its diaspora, I often receive advance notices of exhibitions or publications involving Asian or Asian diasporic artists. But around 2021, I observed that these notices had shifted from the contemporaneous to the retrospective: many of them were posthumous projects about artists who had never received their proper due. At first, I was not cognizant of this shift because resuscitating an artist and their work requires reaching into a time that is not contemporary, echoing my experience of writing about non-Western artists. I don’t recall if I was excited when this “trend” became obvious to me. But at present, my posture toward it could be described as tentative and suspicious. Still, I find myself defending the necessity of this kind of historical resuscitation when in the company of folks who might disapprove of it.

“The narrative of Western art history is organized with the presumption of time’s linearity. Discussions of non-Western artists usually occur outside of this framework, their contributions ascribed a characteristic of submergence or exceptionalism, not seeming to take place in time.”

In defense, I insist that what might seem anachronistic in historically resuscitative work is not, because such a claim gives too much credence to the experience of time, knowledge, and history as authoritative. As the late Japanese-American curator Karen Higa has pointed out, even the American modernist canon conjures a narrative of nonlinear overlap and influence: “The past was marshaled to create a specific view of art of the various presents. If Monet and Turner could be seen as anticipating the light, color, and allover compositions of Abstract Expressionism, as precursors they could validate the present, make it more understandable, and link American art of the mid-twentieth century to a longer-standing, European tradition.”1 Higa’s words complicate our understanding of the linearity of modern art history, which for me creates breathing room in a field that has otherwise felt stifling and narrow—in terms of what is viewed, taught, written about, archived, and collected.

This urge toward belated reckoning has helped me work through hardships I have witnessed beyond the realm of art, such as in the life of my mother. After she immigrated to the United States, the nail salon industry usurped her life. She worked without health insurance or a stable salary, knowing that one missed day of work would leave a mark on that week’s expenses. The work itself was strenuous—she developed allergies due to the chemicals, back and neck pains from constant leaning over, and compromised eyesight from straining to look at minute details.

Distinctions between anachronism or contemporaneity dissipate for lives that are squeezed to be lived in such small crevices. When there is no time, one’s present retains a peculiar quality, as every moment is lived in the shadow of past pain and in preparation for future discomfort. Perhaps lives such as my mother’s legitimize the act of looking back at things that did not receive care in their own time. My incessant need to write about her testifies to this.

But my belief in the radical possibility of time’s elasticity, and the potential this might offer to rethink history, mocked me like a cheap sentiment when my mother passed away only four months after her cancer diagnosis. It dawned on me: my writing had not been evidence, but an incantation. I hoped that my writing would anticipate a future where she and I would find ourselves living together. I don’t mean that we would exist in the same house, but in the same time. I would no longer be mulling over how to most efficiently summarize my day whenever I would catch her for a chat before she went to sleep. She would be living in the time of my living, and I in her time.

“Distinctions between anachronism or contemporaneity dissipate for lives that are squeezed to be lived in such small crevices. ”

The breathing room that I had previously felt in posthumous recognition became suffocating. By reducing her to a victim that required my saving, I realized that retelling stories of my mother replicated the dynamic of curatorial projects framed as “tributes” to artists who had been erased by history. As Saidiya Hartman asks in “Venus in Two Acts,” “Is it possible to construct a story from ‘the locus of impossible speech’ or resurrect lives from the ruins? Can beauty provide an antidote to dishonor, and love a way to ‘exhume buried cries’ and reanimate the dead? Or is narration its own gift and its own end, that is, all that is realizable when overcoming the past and redeeming the dead are not? And what do stories afford anyway? A way of living in the world in the aftermath of catastrophe and devastation? A home in the world for the mutilated and violated self? For whom—for us or for them?”2

Even if I could accept and proclaim that my mother’s life was not wasted—what sort of life am I making for myself, if my way of experiencing the people and art I love is through a remove? Too much of my mother’s life was lived within the confines of the nail salon, and I was deprived of her touch, voice, and involvement in my life. Of course, her life and our relationship were still real. Unlike Venus and the countless Black women whom she is meant to symbolize, my mother’s life was not completely unwritten and unknowable. I still have some memories of her that I can look back on. But how could I claim to know about the vulnerability of relation and entanglement that marked her existence? My grief is not just born from my wish that I had more time with my mother, but from a devastating recognition: if that time were to be granted to me, I might not actually know how to be with her.

⁂

Genji Amino, a poet, writer, and curator, has dedicated nearly a decade to researching, preserving, and honoring the life and work of their grandfather, the Japanese-American sculptor Leo Amino. Leo passed away just before Genji’s second birthday, and therefore only exists to them through the memories of their grandmother and mother, as well as through Leo’s art and archives. In my grief for my mother, I thought often about Genji, because I felt a camaraderie with them as they too were reaching toward an ancestor whom they did not intimately know.

Edited by Genji, Leo Amino: The Visible and the Invisible (2024) is the first monograph of the artist. They borrow the title of the opening text, “audience / distant relative,” from Theresa Hakkyung Cha’s 1977 eponymous mail-art piece. To Genji, Leo is, as Theresa writes, a “distant relative / seen only heard only through someone else’s description.”3 Though I had been feeling disillusioned about posthumous projects, the way Genji sought to know their grandfather resonated with me as courageous and honest—they named their distance to Leo, and by naming it, dared to close it.

From what I knew of Leo’s work, it seemed to me to contain an invitation to ask and think through the questions that plagued me about delay, distance, relation, and entanglement. The key concern of Leo Amino’s sculpture was the idea of transparency—the relationship between things, how they are encountered or intermingle. In a rare statement accompanying the publication for the 1955 exhibition New Decade: 35 Contemporary American Painters and Sculptors at the Whitney Museum, Leo writes:

“It is interesting to note that transparent form displaces space just as any other, yet the distinction between the physical aspect and surrounding space is less conspicuous due to its transparency. However, refraction and optical illusions created by light on transparent form—though they appear to be inconspicuous—actually intensify the difference, thus creating a greater sense of three dimensionality.” 4

I initially assumed that Genji invoked Theresa in their text simply because she had given them language to think about the texture of their experience of their grandfather, not because they saw any overlap between Leo’s work and her own. But in reading Leo’s words, I realized that his exploration of how transparency and light manifest in space reveals an incisive understanding of ontology similar to Theresa’s. Theirs is a relational ethic where different elements are vulnerable to the other. Rather than intensify the difference between form and space through obstruction, Leo’s refractional sculptures, such as Refractional #44 (1969), sensuously display entanglement in action. Vito Acconci articulates the slipperiness one might experience while viewing Leo’s work in a review he wrote a year after Refractional #44 was made: “The over-all form looks solid, holding the viewer away from it, while the inside is elusive and tempts the viewer in. Seen from one direction, there is an agglomeration of color, while seen from another, the color almost disappears; the color has no edge, the viewer enters it unconsciously.”5 Leo’s edgeless agglomerations of color recall Theresa’s language about spillage. In her seminal work Dictée (1982), she writes, “[The] stain begins to absorb the material spilled on.”6

A stain is typically the aftereffect of an action, a blemish that sullies but does not obliterate the material fully. But in Theresa’s account, the stain becomes the agent that absorbs the material. Both Leo and Theresa posit a different philosophy of relation that reorients the accepted notions of order by subverting the usual relationship between subject and object—leaving us only with the encounter itself.

⁂

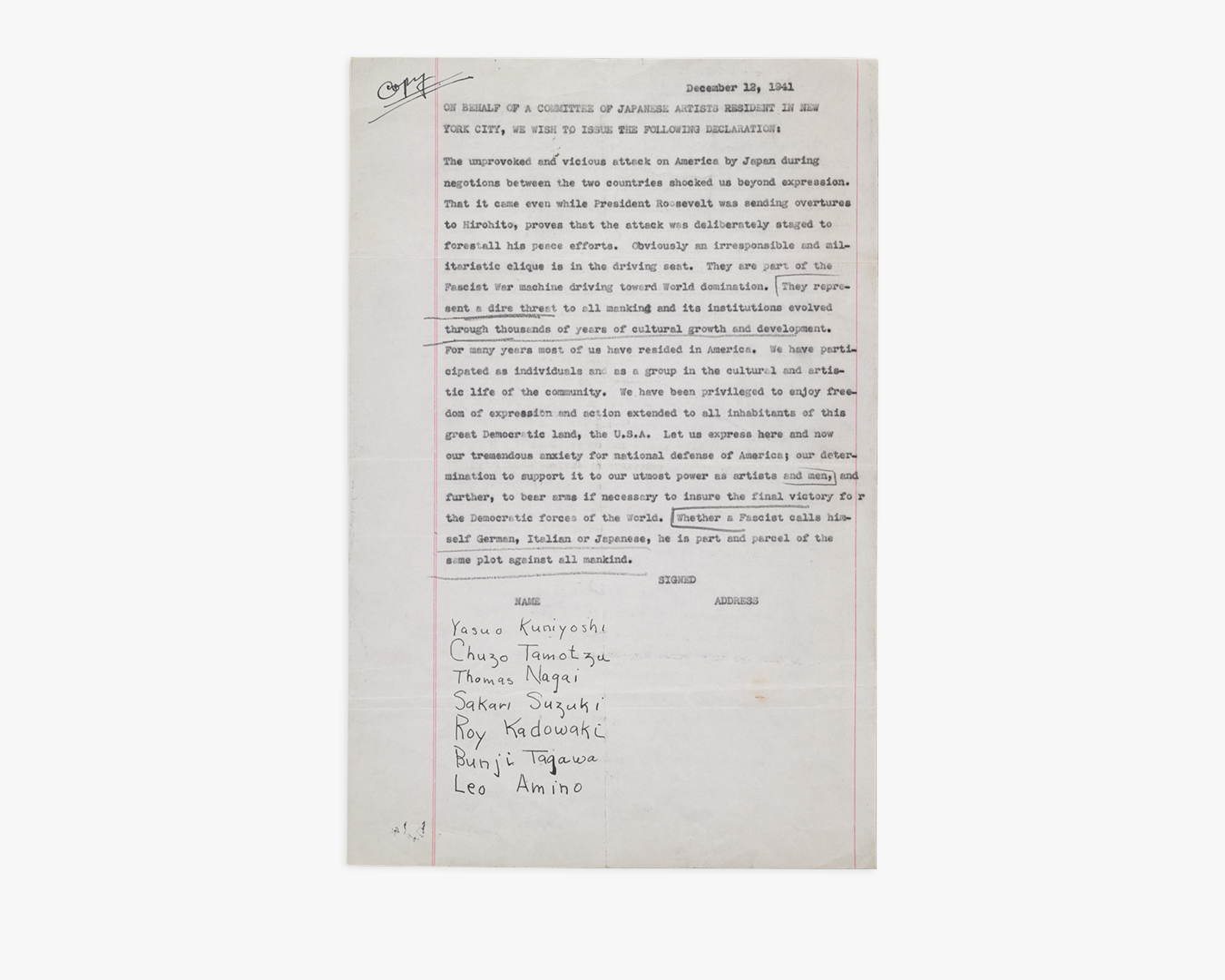

How a person becomes who they are cannot simply be attributed to their upbringing and experience. Whether by nature or necessity, Leo did not feel tethered to precedence. Julie Amino remembers her late husband: “In the larger sense of the word, all Leo’s life was an experiment—leaving Japan to experience another way of life, leaving California to become an artist in New York. This was the way he lived, how he worked, and what he taught until the end of his life.”7 Born to a Japanese family in occupied Taiwan (Formosa), Leo began his life as an outsider. He was seven when his family returned to Japan; locals likely viewed as an anomaly. After his father passed away, he left for San Francisco alone, despite the expectation that his being the eldest meant he would take the place of the family patriarch. Leo arrived in the United States in 1929, just five years after the 1924 Immigration Act restricted Asian immigration. He would work as a picker on dry fruit farms in the summer, and in other seasons would work as a “schoolboy,” or live-in domestic help for white families. The Japanese invasion of Manchuria in 1931 confirmed Leo’s decision to remain in the States: he knew that if he returned to Japan, he would be drafted into a war that he did not believe in.8 He left California after six years due to growing anti-Japanese sentiment and came to New York, eventually taking a job at a Japanese import-export company that dealt pre-cut wood, paving the way for his first sculptural experiments. By 1939, when his work first reached an international audience at the New York World’s Fair, he’d quit his job in order to devote his time to sculpture, moving into a basement apartment and supporting himself by giving private lessons.

Leo forged his own path—but in a way that was markedly different from the spiritual characteristics of the American pioneers, or the Abstract Expressionists of his generation. He spent most of his life working in his Perry Street studio in Greenwich Village at a time when the Abstract Expressionists met at the nearby Cedar Bar, but he preferred not to participate. His experimentation was rooted in phenomenology rather than the heroic gesture or subjectivity of the Ab-Ex artists.

In 1945, Leo began his first experiments with polyester resin, after it was declassified by the military following World War II. Though critics praised Leo for his innovative use of the new material, their support does not necessarily indicate that his work was understood, nor did it prevent his eventual erasure from art history. As critic Aruna D’Souza writes, “Because of Amino’s status as ‘the first’ – the first American artist to work largely in plastics, the first artist in the world to work in cast plastics – it is natural to focus on that aspect of his singularity in discussing his work … But it is interesting to me, too, that for Amino, plastic was one material among many, all working in service of a practice that was deeply phenomenological.”9

Previously, he had made sculptures using materials such as wood, plaster, magnesite, and wire. What excited Leo about plastic was the way it allowed him to consider color as inherent to the sculpture, rather than as an added element. When instructing his students how to handle any material for sculpture, Leo had been known to repeat, “It will tell you” in his typically enigmatic and aphoristic way. His process was as improvisational and durational as a conversation.

The sculptures in Leo’s Refractional series (1965–1989), for which he is most known, appear pristine and precise. But they are all born from questions he asked through his work, not preconceived notions of what sculpture should look like or be about. If he was embedding solid objects into liquid resin, he would have some time to move them around before they cured, as in Composition #8 (1947), and where they would fall would be determined in dialogue with the response of the materials to one another. Pieces such as Landscape II (1956) reveal Leo’s concerns with transparency—how forms interact with one another, as well as what happens to the forms upon the viewer’s encounter. Here, a carved rectangular wooden plane is augmented with negative spaces, which are further segmented by small, slender wooden biomorphic forms that recall handheld tools. Works such as Green Manor (1957) make evident Leo’s exploration of how form would interact with light and space, not only through its shape, but through its very material. Though it seems as austere and impenetrable as bronze, it is in fact a lightweight structure, made of polyvinyl acetate and sand, the hue and surface the result of alchemy between various materials.

⁂

1952 – 1977 Leo Amino teaches at Cooper Union

1954 – 1957 Eva Hesse attends Cooper Union

1960 – 1964 Jack Whitten attends Cooper Union

1974 – 1995 Jack Whitten teaches at Cooper Union

On August 3, a few days ago prior to writing this, I attended the one-hundredth birthday party of Julie Amino, and sat across from her and Mary Whitten, spouse to the late artist Jack Whitten. Both Mary and Jack had been students of Leo’s at Cooper Union’s night school. There was much celebration in the air that evening: my own birthday was the day before, and Jack’s major posthumous retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art had also closed on the same day. Julie, who Genji says is not often at a loss for words, was visibly overwhelmed. Tears flowed when Eriko—Julie and Leo’s daughter, and Genji’s mother—read lyrics from a song that included the line, “Leo is here.” Both Mary and Julie talked about how they missed their partners and wished they could have been present. There’s so much that I could write about that night, but I am still processing it. What remains with me is something I overheard Mary ask Julie: “Can you believe it is Cooper Union that brought us together?” Her question could be interpreted as a nicety, as simply something that “people say” to each other. But now, weeks later, her words seem to escape their original context and return to me as a new message, one with its own life and meaning. They make me recall a handwritten note that Jack left on a napkin, which I saw reproduced in the catalog for the 2022 Dia Beacon exhibition Jack Whitten: The Greek Alphabet Paintings:

“Not an illustration of an idea but the material embodiment of the idea: the idea expressed through materiality of paint, wherein its [sic] impossible to separate idea from process from material. Conceptually the idea is always in a state of being formed. What’s important here is that no separation of image, content, idea process is allowed, it’s all compressed in the making of the object.”10

After remembering the above, I felt like a detective close to solving a mystery unbeknownst to myself. I flipped back to a reproduction in Genji’s Leo Amino: The Visible and the Invisible of notes from a sculpture course that Leo taught:

Difference in question of space between 2D & 3D

2D- space confined by borders, edges—more illusionistic

3D- space all encompassing—none separability11

My mind turned to Eva Hesse. Although she may never have studied with Leo directly, he would have been the only sculptor in New York actively exhibiting cast plastics during her time at Cooper in the mid-1950s, before she would begin her experiments with fiberglass casting a decade later. In her published diaries, she wrote:

“The painting that is of importance is never the one where the aesthetic stands alone and is both the forms + content. The aesthetic is a means to an end. It should not be viewed in and by itself – it is the by product of an idea which is content.”12

The notes from both Jack and Eva refer to painting. Jack speaks of paint’s “materiality,” while Eva talks about the whole form of the painting as being one with its content. Both artists would strive to move away from the “illusionistic” and toward the “non separability” that Leo centered in his teaching.

Mary’s words prompted me to think back on the modi operandi of these artists, as well as my choice to bring them together into the shared space of writing. There is no ego in being “brought together,” as it is not the result of a personal decision to meet someone. To be brought together is precarious, delicate—for it is just as likely that they could have been elsewhere. It is acknowledging that a distance was closed.

Leo devoted a third of his working life as an artist, from 1965–1989, to the Refractional series, knowing he had come upon something significant. Insatiable combinations of color, angle, and light interact with forms contained within form. Their shifting geometries appear to mimic shapes we think we know and have seen, but then defy expectations. An early unnumbered refractional, Untitled (1966), and a later piece from 1987, Refractional #229, stand erect only to reveal angles, curvatures, and inclusions that cause color to travel at varying speeds. In one view, Refractional #106 (1975) seems to be made of triangular prisms meeting together—resisting our urge to call it a rectangular prism, disorienting our perception of its center of gravity.

In different ways, both Eva and Jack shared Leo’s impulse toward obsessive repetition. Eva lauded its tendency to exaggerate and make meaning more meaningful; her Accession II (1967) is an open cube of galvanized steel with plastic tubing threaded through the exterior to reveal a repetition of bristles in the interior. In his “tesserae,” Jack arranged sliced pieces of paint in tiles on canvas to create cosmic works, such as Atopolis: For Édouard Glissant (2014). Works like these make me think of a series of resin constructions that Leo created from the late ’50s into the early ’60s by cutting sheets of acrylic in varying dimensions and thicknesses, which he then glued together to form a relief sculpture that could be viewed from all sides. Horizon (1962) feels reminiscent of a screen or a window, where different degrees of transparencies and opacities form a sort of crystalline geological landscape. I don’t want to presume direct influence, but there’s no doubt Jack had seen Leo’s resin constructions when he was invited to Leo’s studio as a student.

The Brazilian anticolonial Black feminist philosopher, Denise Ferreira da Silva, offers another articulation of these artists’ modalities:

“The method I am after begins and stays with matter and the possibility of imaging the world as corpus infinitum. […] It is one in which everything is indeed always already also an expression of everything else in the unique way it can express the world—imagine difference without separability […] The Dead’s words have ethical force: everything for everyone. For if the flesh holds, as a mark/ sign, colonial violence, the Dead’s rotting flesh returns this marking to the soil, and the Dead then remain in the very compositions of anything, yes, as matter, raw material, that nourishes the instruments of production, labor, and capital itself.”13

My understanding of distance previously defaulted to a vision of bridging a past and a predetermined future, an addresser and an addressee. Time only seemed to move persistently forward, knowing one direction. But to bridge the distance between my mother and myself, or to posthumously resuscitate artists’ legacies, often felt as forced and painful as the suffering that caused their initial exclusion. Moreover, the labor to resuscitate seemed to require sacrifice of being in the present.

But Leo, Eva, and Jack provoke me to envision the simultaneous. Though their lives were marked by war, displacement, and different forms of marginality based on race and gender, they allowed their work to stretch in space or let space stretch within it. The “all encompassing” drive within their practices was not a flattening or a disappearance of difference, but an investigation of the way things touched, reacted, and existed together. What extends and expands goes on infinitely, but this is not about sequential time. There is a suspension that takes place—the beginning keeps beginning.

I am no longer conjuring or calling to my mother. Instead, I know that she exists in my words, in their very fibers. This is not to say she speaks through me, as if I have become her vessel. No, it is rather that if I commit to living with the awareness of her life, my words could bear the force of her flesh. For her life did not vanish, it has created mine. As da Silva writes, “the Dead then remain in the very compositions of anything.”

Dear Mark. It seems we have been in the same place listening to each other all along.

Diana SeoHyung is a New York based-writer and translator. Her writing has appeared in Art in America, ArtAsiaPacific, The Brooklyn Rail, Flash Art, Momus, The AMP, Hyundai Artlab Editorial, and others. She is the recipient of the 2024 Toni Beauchamp Prize in Critical Art Writing. She is an immigrant, born in Seoul, South Korea, raised in Queens, New York, and is a mother of a six year old called Mark.

Banner Image: Leo Amino, Refractional #44, 1969. Courtesy of the Leo Amino Estate. Photograph by Alex Yudzon.

NOTES

1. Karen Higa, “The Search for Roots, or Finding a Precursor,” in Hidden in Plain Sight: Selected Writings of Karin Higa (New York: Dancing Foxes Press, 2022), 328.

2. Saidiya Hartman, “Venus in Two Acts,” Small Axe, Number 26, 12, no. 2, (2008): 3.

3. Theresa Hakkyung Cha, Audience / Distant Relative, artist’s book (N.p.: Self-published, 1977).

4. Quoted in John I.H. Baru, ed., New Decade: 35 Contemporary American Painters and Sculptors, exh. cat. (The Whitney Museum of American Art,1955), 8–9.

5. Vito Acconci, “Leo Amino 1970 solo show East Hampton,” ARTnews, May 1970, 20.

6. Theresa Hakkyung Cha, Dictee (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001), 65.

7. Julie Amino, “Auld Lang Syne,” in Leo Amino: The Visible and the Invisible, ed. Genji Amino (New York: Radius Books, 2024), 245.

8. Leo Amino, like the majority of Japanese Americans living outside of the Military Exclusion Zone established along the West Coast of the United States by Executive Order 9066 following Pearl Harbor, was not among the more than 125,000 Japanese Americans evacuated to incarceration camps in 1942. Spared confinement and dispossession, he was placed under travel restrictions and made to translate for the Navy for the duration of the war. During this period Leo served alongside Isamu Noguchi, Yasuo Kuniyoshi and others on the Executive Board of the Arts Council of the Japanese American Committee for Democracy, an anti-fascist civil rights organization in New York.

9. Aruna D’Souza, “How to Live in a Plastic World,” in Amino, 16.

10. Donna De Salvo and Matilde Guidelli-Guidi, eds., Jack Whitten: The Greek Alphabet Paintings, ex. cat. (Dia Art Foundation, 2023),202.

11. Leo Amino’s notes for his course, Three Dimensional Design, at Cooper Union, New York, 1970. Quoted in Amino, 280.

12. Eva Hesse, Eva Hesse: Diaries (New York: Hauser & Wirth, 2020), 842.

13. Denise Ferreira da Silva, “Reading the Dead: A Black Feminist Poethical Reading of Global Capital,” in Otherwise Worlds: Against Settler Colonialism and Anti-Blackness (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 2020), 42–43.