Scoring Space: Pan Daijing at Walker Art Center

In her review of Sudden Places, Berlin-based artist Pan Daijing’s first U.S. solo museum exhibition at the Walker Art Center, Mariana Fernández considers the ways we locate ourselves in the museum when conventions of legibility and interpretation are stripped away, and our own presence is privileged. An artist with few disciplinary limitations who employs the conceptual language of performance, Daijing presents a set of conditions for the viewer to set the boundaries of their own experience, intimately and individually, decoupled from a more collective audience. Bringing her memories of the exhibition into the present moment of writing, Fernández frames Sudden Places as a score, one continually revealed through multiple temporalities and modes of perception.

– Lumi Tan, 2025 EIR

The scene begins in darkness. As my eyes train on the sliver of sunshine emanating from the centimeters-wide aperture in the far wall of the space, I think of George Balanchine’s famously deadpan quip to a critic asking what one of his ballets was about:

“About twenty-eight minutes.”

Sudden Places, Pan Daijing’s exhibition at the Walker Art Center, is similarly transitory, its identity too blurry to be reduced to the kind of pithy summary demanded by Balanchine’s critic. It takes a moment for the senses to adjust to the darkened gallery space, which is illuminated only occasionally by the shifting flashes of light coming from portholes and videos. Here is a performance devoid of bodies, its temporality hinging on the choreography of scant visual and sonic gestures demanding detective-like piecing together. But the exhibition is still about something. Without actually meeting the conditions of a live event, Daijing works through the live as a method of making, refusing the services to which it is regularly conscripted to instead experiment indefinitely with the interconnected afterlives of objects and actions.

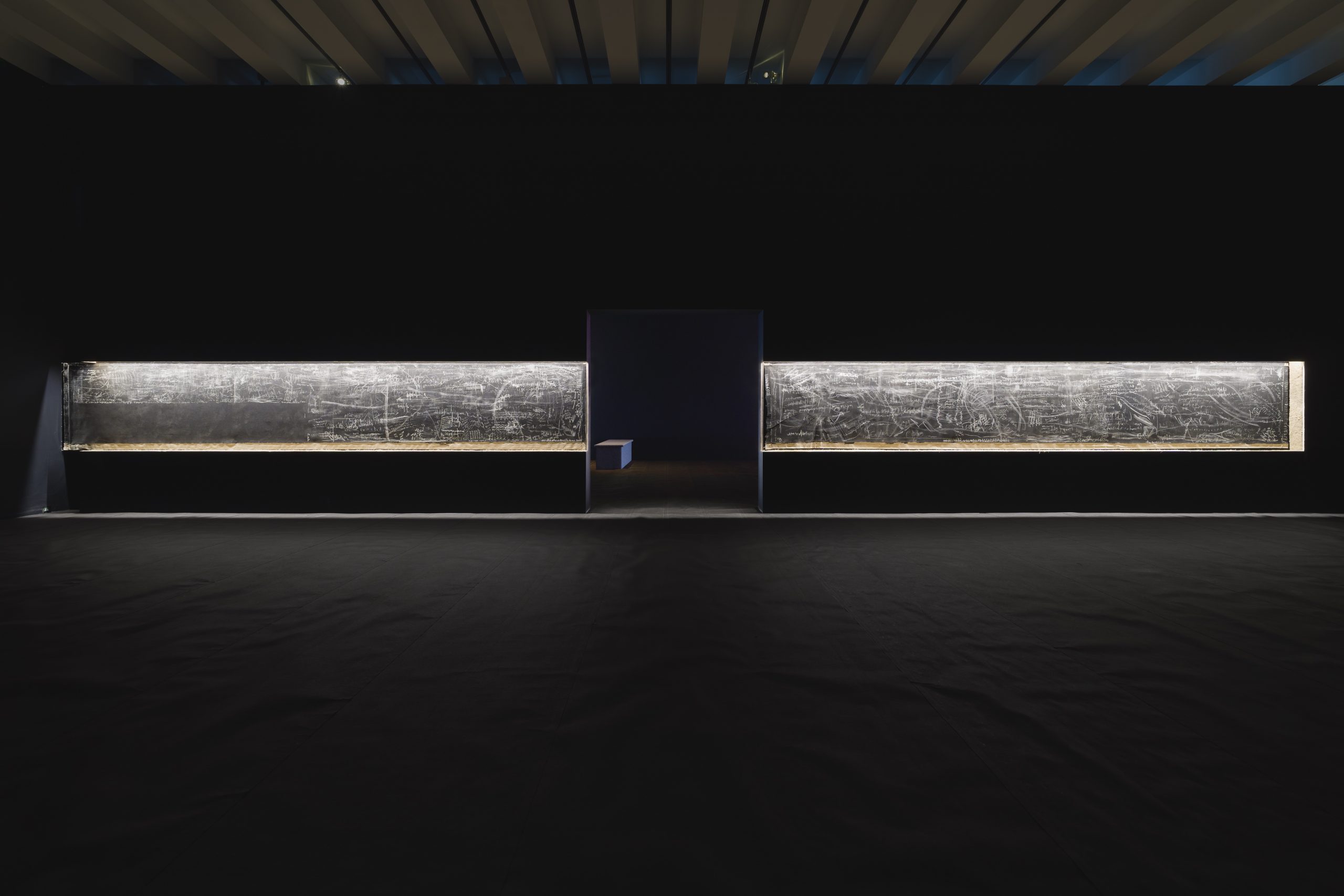

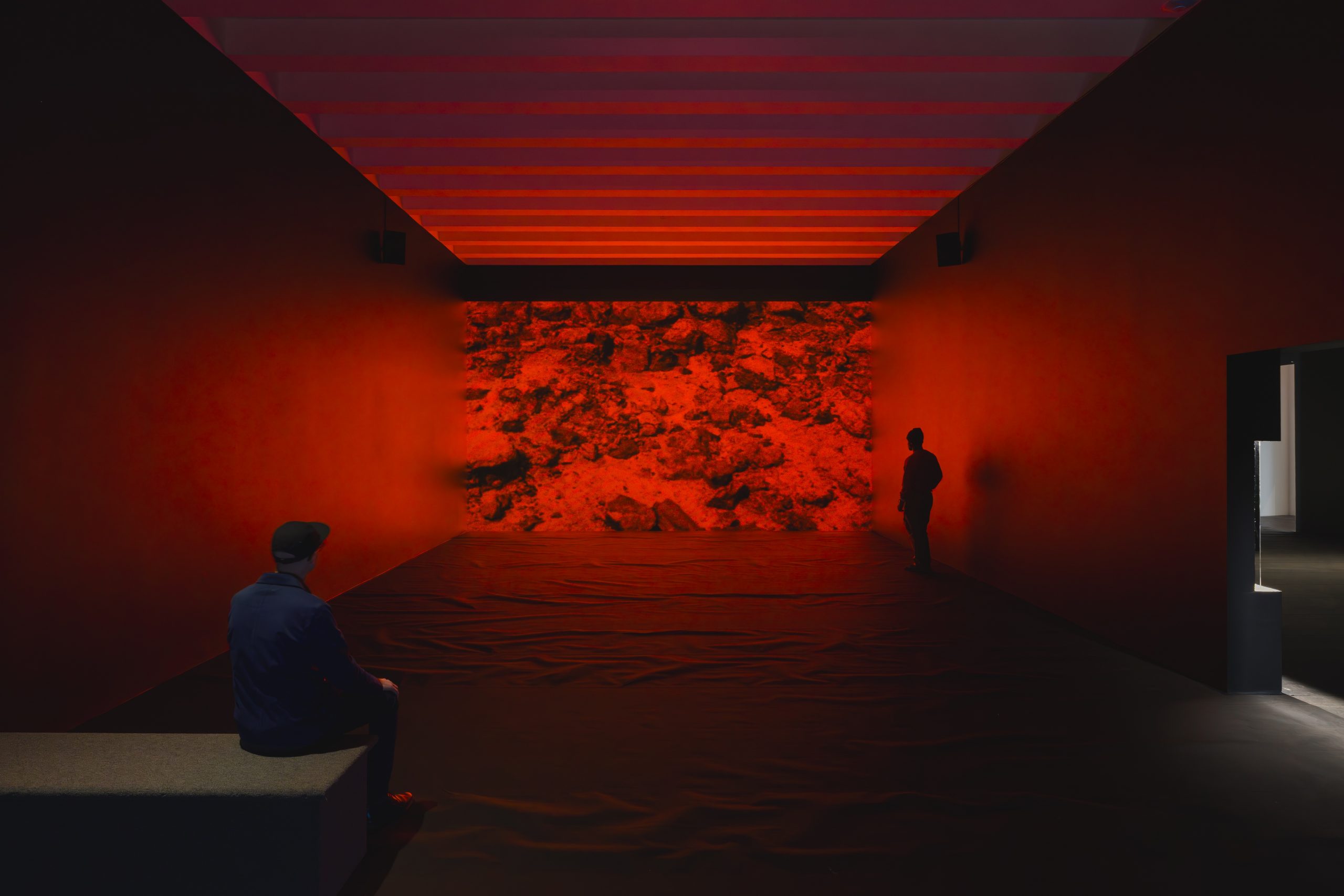

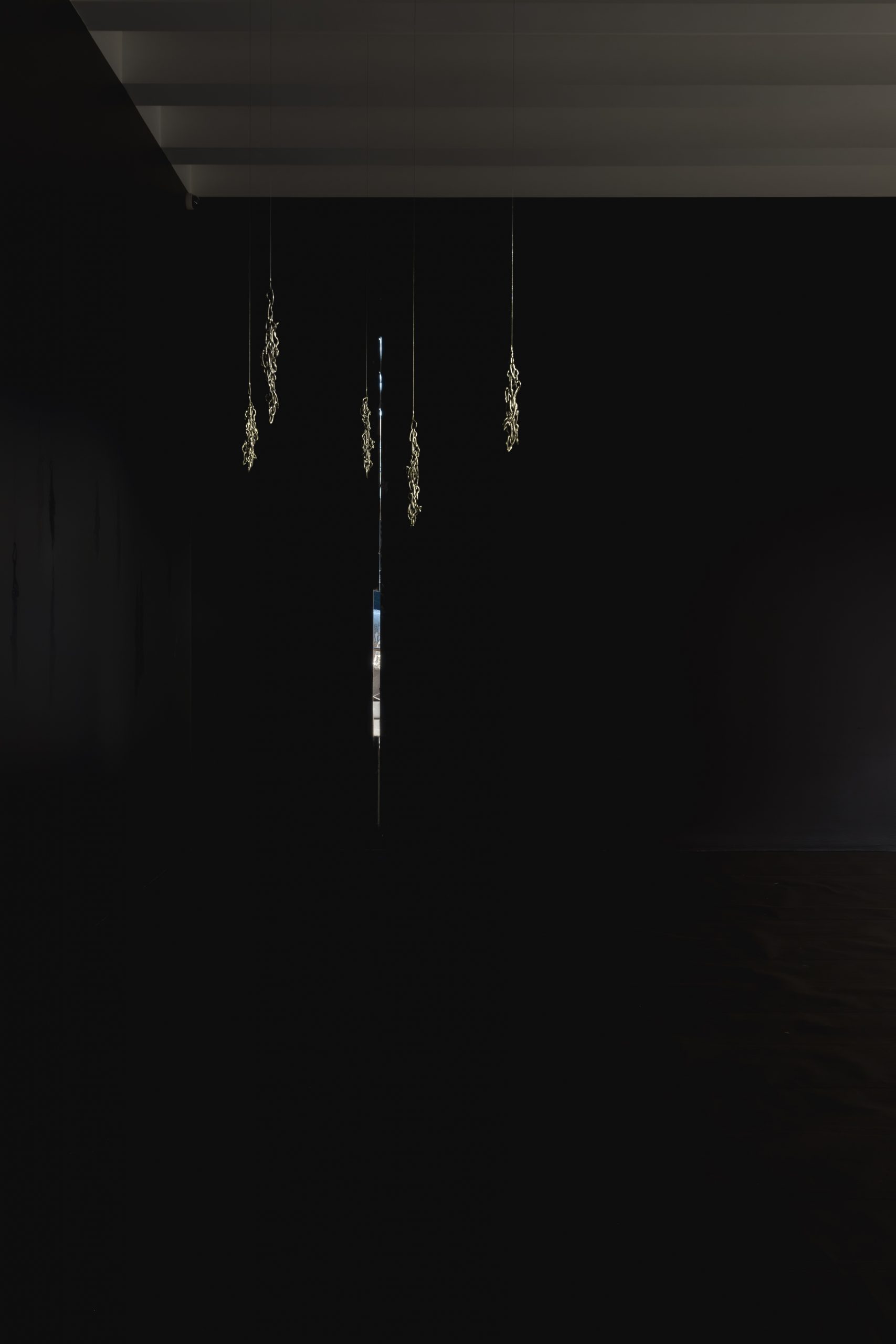

Installation view of “Pan Daijing: Sudden Places,” Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, 2025. Courtesy of Walker Art Center. Photograph by Eric Mueller.

“I don’t make music. I reveal sound,” the artist said in conversation with the show’s curator, Pavel Pyś. There is a sort of Cage-like radical passivity in Daijing positioning herself not as a maker of new sound, but as a maker of conditions whereby the sounds already present in the environment can be attuned to. Yet Daijing’s statement neglects the agential component of composing that her work so carefully hinges on. As a self-taught noise musician, she approaches the physical space of the exhibition as a material to be scored—through sound, yes, but also through a network of paintings, sculptures, films, videos, and architectural interventions designed to amplify and distort the architectural specificity of the environments they navigate. Six core works and several untitled interventions anchor Sudden Places. They spill into each other and throughout the building, contingent on events of mutual connectivity and dependency stretching over time.

In the essay “Give Me A Gun and I Will Make All Buildings Move,” Bruno Latour and Albena Yaneva argue for abandoning the view of buildings as static objects and returning to an understanding of architecture as an interconnected network of forces—as a living, breathing organism. Daijing’s previous exhibitions have consistently used architecture as a metaphor for the body. In the installation Done Duet (2021), commissioned for the 13th Shanghai Biennial, she recast the silos of Shanghai’s Power Station into a spine, with liquid and sounds descending from the ceiling as if the structure were undergoing a lumbar puncture—a procedure the artist went through several times as a child. At Martin Gropius Bau, Berlin, the performance Dead Time Blue (2020) transformed the atrium “into an opening and compressing lung” through a chorus of live and disembodied operatic voices pulsating through the space. Sudden Places is more subtle in its articulation of architecture-as-body; it inflects the gallery with liveness by toying with how the audience moves through architectural space.

Tar-impregnated felt spans the entire floor and demarcates the bounds of the exhibition. It carries a subtle aroma and scratchy, uneven texture, urging viewers to attune themselves to the space’s small details and to their own movements within it. This call to heightened awareness extends throughout the Walker galleries, where sparse, subtle works often verge on the imperceptible. There are tiny photographs hidden within corners, beckoning visitors to crouch and strain. Light slips between crevices and slits, creating the illusion of mirrors, destabilizing perception. Another intervention is still easier to miss: Untitled (2025) is a fissure about the size of an eyeball cut into the back wall of the first gallery. From afar, it casts a thin streak of light onto the darkened gallery space, and up close provides a partial view of the tubes, cladding, and aluminum vents that make up the building’s latent skeleton. As if the museum were an archaeological site to excavate, Daijing has crept into the interstices of the building and brought them into the pristine gallery, redirecting audiences to think about what makes art—structurally, and therefore experientially—possible.

“As if the museum were an archaeological site to excavate, Daijing has crept into the interstices of the building and brought them into the pristine gallery, redirecting audiences to think about what makes art—structurally, and therefore experientially—possible. ”

Daijing treats these works not as autonomous objects but rather as links in a larger discursive chain concerned with how subject and object, body and space, are mutually constituted. As Maurice Merleau-Ponty writes in his 1945 book Phenomenology of Perception, our experience of spatiality is not a detached, intellectual process, but something deeply grounded in our bodily existence—our body’s senses, movements, and limitations. Apart from Untitled, none of the interventions are given a wall label or title, refusing the visibility and access that a checklist provides. Piecing together what each work is, which spatial parameters belong to it, becomes an exercise in thinking of one’s collective or individuated self within these larger structures of interdependence.

Nestled within the back of the gallery is a tiny television monitor on the floor, which displays looping footage of a lighthouse beam periodically casting its glow over the ocean. The light rotates and paces with a rhythm that echoes sound waves and establishes temporary sightlines throughout the show. It illuminates while leaving other spaces in darkness, quietly holding the show together. Rather than a fixed presentation, the exhibition space functions as structural frame: a testing ground for juxtapositions between darkness and light, materiality and ephemerality, hard and soft, sharing and withholding. It is through these tensions that, intermittently, thematic chords of doubt, confusion, introspection, and reciprocity materialize.

Oscillating between revealing and concealing, Scale Figures (2023/2025) is a “composition in three parts”—sound, sculpture, and architectural intervention—that begins with the oscillating voices of two opera singers. The fleeting call-and-response pattern of a countertenor and a mezzo-soprano pulses through the gallery walls, while overhead a series of custom-made, tendril-like brass sculptures float from the ceiling like a cast of dancers that can appear either heavy or nimble, depending on the vantage point. The third part of the work comprises several inkjet prints that have been fastened with metal clamps to an unnamed part of the Walker campus’s infrastructure. By withholding the work’s location, Daijing draws the audience into a kind of egg hunt within the museum—one where the search itself, and the act of movement, quickly eclipse the object of pursuit.

All of Daijing’s performances and exhibitions inflect and sample from another, forming a symbiotic body of work that uses the process of revision to examine the temporality (and indeterminacy) of embodied and shared experience. Two horizontal black-and-white paintings, densely layered with abstract accumulations, originated in Daijing’s exhibition Mute at Haus der Kunst, Munich (2024). During brief intervals of the six hour-long durational performances that took place daily throughout the show’s run, performers either moved against the wall with smashed chalk in their pants or blindly scrawled their names across its surface. The cumulative actions evoke incantatory mark-making or automatic writing, as well as much of the ordinary, untrained movement of postmodern dance. My mind goes to Trisha Brown’s Untitled (2007), the byproduct of a dance she performed on the surface of a sheet of paper while moving a stick of charcoal with her feet: a symbol of an action, or, less optimistically, the residual markings of irrecoverable movement.

“All of Daijing’s performances and exhibitions inflect and sample from another, forming a symbiotic body of work that uses the process of revision to examine the temporality (and indeterminacy) of embodied and shared experience.”

By encoding movement into drawing and asking viewers to read dance into the gesturalism of mark-making, Dajiing muddies the distinction between the liveness of performance and its representation, its after-image. The resulting paintings, Cream Cut 1 and Cream Cut 2 (2024–2025), span the gallery’s central wall, displayed on receded niches surrounded by exposed sheetrock, as if someone had ripped the wall open and found the paintings inside. Though the ephemeral moments from which these paintings were created are lost, the immediacy of performance is reinstated through the physicality of the gesture and the crudeness of the chalk lines “dancing” across the surface. Daijing’s work toys with the idea of the exhibition as a ground for continued making—a space for tearing apart, quite literally, but also remembering, tracing, and transfiguring past encounters.

The same sensibility carries into her video works, which seek to stretch and reconfigure the event of performance. Faint (2023–2024), a moving image work displayed on small television monitors on the floor of the second gallery, is another duet between performer and instrument, the latter here a camera. Each of the four channels of the piece was shot with a handheld camcorder during the development of several performance works. The camera resists the temptations of spectacle, instead alighting on fingers gliding over Marley flooring, bodies entangled in choreographies, or moments of stillness and impasse—all of the many things that go into making a dance. The small scale of these filmic images contrasts dramatically with the magnitude of the work projected on the wall of the opposite gallery, The Hour Between Dog and Wolf (2021–2024). Directed and partially shot by Daijing over the course of four years, this loosely scripted short film compiles footage of rehearsals, performances, and travels across Hong Kong and Europe. Moments of isolation abound. We see a male performer rehearsing before the camera, glitchy and overexposed, and a lone figure making their way through a darkened tunnel. But there are also black-and-white vignettes of people in close interactions: hands interlock, torsos come together to embrace. All the while, the camera moves in and out of focus, presenting each sequence as an incomplete memory fragment to be altered and replayed, perhaps infinitely.

Segments of the film have been shown as individual projections in previous exhibitions, most recently in Until Due Time, Everything Is Else at Grazer Kunstverein in 2023. Spliced together, they visualize the interconnection of solitude and shared experience, appearing as both echoes and reverberations of the recollected moments that make up an artistic practice. Rather than attempting to distill ephemeral experience into something that can be repeated, the film harnesses the romance of fleeting experience, the sensation of fullness we experience in moments when it feels like there is no future and no past, only a paradoxical present in which time appears to spin in ever-faster circles and yet stand perfectly still.

Though they both cull from works in progress, Faint depicts processes of creation, while The Hour Between Dog and Wolf centers Daijing’s memories of the former. Trying from a distance, to remember the scenes of each work—to re-insert my own faded impressions into my present consciousness and to translate Daijing’s slippery practice into my porous one—feels like inching closer to the crux of the exhibition. How do we hold these two states together? How do liveness and its residues circulate across media, stay in bodily memory?

One scene of The Hour Between Dog and Wolf depicts flickering lights behind a windowed building façade, briefly piercing the room’s intense darkness. In this moment, with no bodies in the gallery to focus on except our own, the bubbly tar floor throughout the space acquires an oceanic vastness, like the waves glimmering under the lighthouse beam in the small video projection earlier on. We become acutely aware of our presence—our breaths, our shuffles and stumbles—within this landscape, which suddenly feels impossibly large. As with all of Daijing’s work, The Hour Between Dog and Wolf trains our attention on intimate details and asks us to consider their entanglement within broader relational systems. It’s about the slowing of time, about embodiment, and about where and how artists make work and how it, and we, occupy space together. But, mostly, it’s about twenty-three minutes.

Mariana Fernández is a writer and curator based in New York and Mexico City. Her essays and reviews have appeared in Artforum, ArtReview, BOMB, e-flux Criticism, frieze, Momus, and X-TRA, and in several exhibition catalogues.