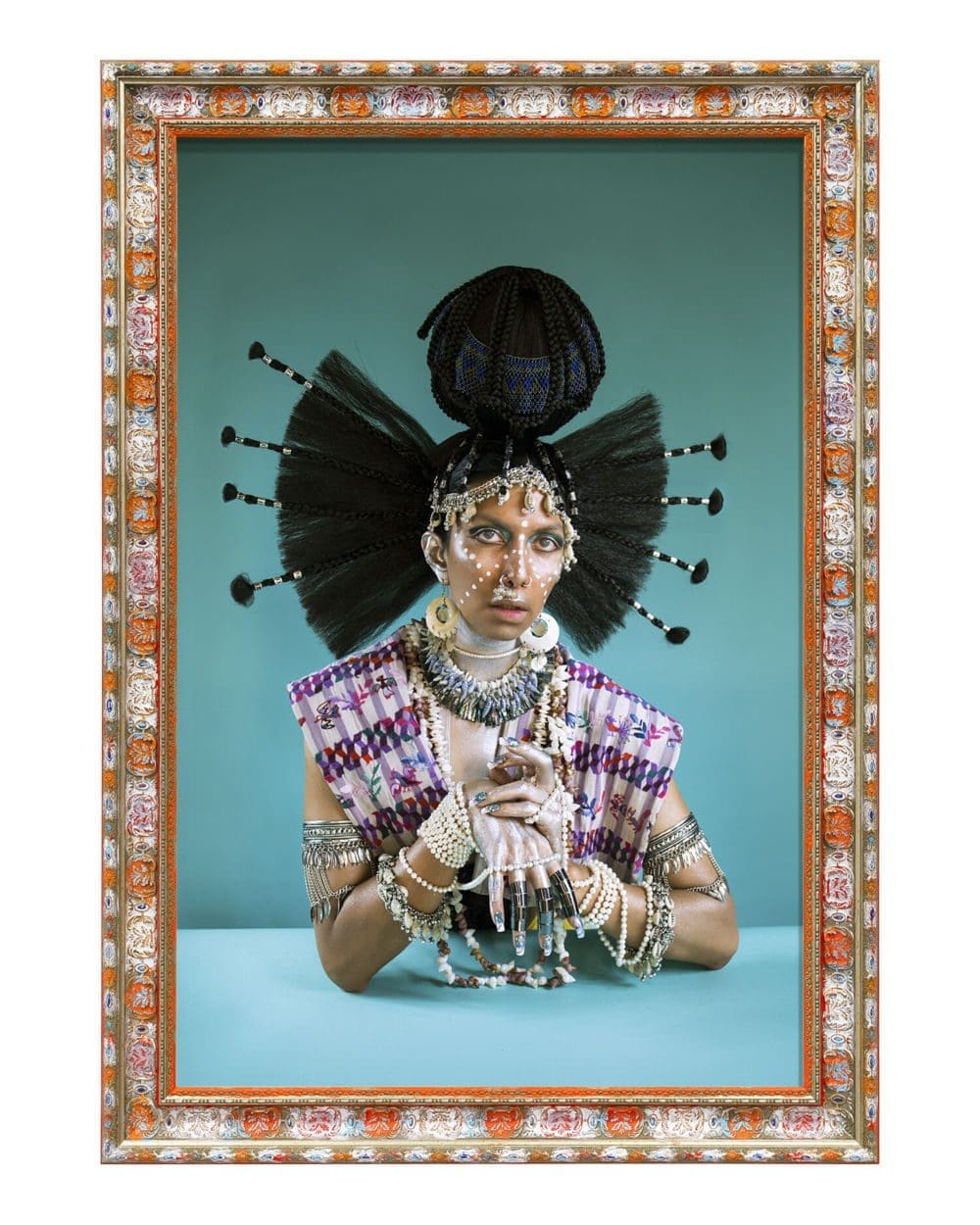

2020 Topical Cream Prize Winner Martine Gutierrez in Conversation with Tiana Reid

Topical Cream is thrilled to announce the inaugural “Topical Cream Prize,” which will be awarded yearly to one artist and one activist whose efforts have made a meaningful impact on their community. Congratulations to Martine Gutierrez who won in the artist category, and Viva Ruiz for Thank God for Abortion who won in the activist category. Winners in both categories were chosen by a special advisory board from the Topical Cream community including Ebony L. Haynes, Dena Yago, Jon Huddleson, Lyndsy Welgos, Marcella Zimmermann, Julia Kim, Yulu Serao, Christopher Udemezue, Ryan Jefferies, and Lena Henke.

In honor of this occasion, Tiana Reid spoke to Martine about the award.

Martine Gutierrez co-creates the world. The artist, who was born in 1989, knew from a young age that her world was a stage ready to be finessed. Through her multi-modal film, magazine, performance, photography, pop culture, and music work, Gutierrez insists on the elasticity of both reality and gender. And authenticity is her catalyst. Not long after she won her Topical Cream award, I talked to Gutierrez about documentation, purpose, going blonde, and being sad and horny at the same time.

Tiana Reid: Congratulations! How do you feel about your award?

Martine Gutierrez: To be recognized by my peers is unbelievable. It feels like being in a physical space with friends, like you’ve got an opening or something, and they’re there to support you and congratulate you. It’s the most real part of being an artist, after you put something out into the world. I feel a little bit like a child when it’s received well.

I’m wondering about your relationship to art as a child.

I made a lot of stuff growing up. We always had a bin of rags or rope. Both of my parents were architects, so there were always drawing supplies and paper around. It was more so my mother who thought I was a star and was like, “I can’t throw this out, I have to put this on the fridge, or we should frame this, or we should send this to whomever you’re thinking about.” That kind of validation from your parent made me feel like, “Oh, I must be good at this. I don’t know, I should keep pursuing this.”

But somewhere there is a box just full of my early drawings of mermaids and fairies and elves and demons, and any kind of mythology. I was obsessed with Medusa for awhile—visual storytelling. Ganesha, people that are part animal, people that always felt … We didn’t have the word “queer” in that way, but I guess that’s what these characters were. They were just of different worlds simultaneously.

When did you start taking photographs? What was that like for you at the beginning?

I was doing video before photography. My dad had a camcorder in the house and I was on camera a lot, so somewhere there’s all this childhood footage of me dragging my dog around and performing for my parents … this obsession with being watched, this childhood vanity. Despicable! But it was kind of like being the subject came first. And then my interests came in, as I would say something like, “Oh, well Dad, I don’t really like how you filmed me. Why did you get that in the background?” And I would start orienting a setting, maybe even dressing up the kitchen or the backyard in some way that felt more like a jungle or felt more like a theater. I learned that within this framework, you can actually start to create a new reality. I guess photography offered even more control over that. It was like a natural progression.

What kind of struggles have you encountered in your work lately?

Feeling like it matters, feeling like there’s a reason to do it at all. I think part of what propelled me forward, naively, was this desire to be recognized, to be famous for being myself, right? I feel like that’s what we’re all logging on to do. You’re like: I will be known for being myself and yet now it’s like, “why?” Why did we want that so badly? And why did it feel so important? I don’t know if I’m a master of illusion. But I’m like, what’s the next illusion? What can be brought into the world that we actually need?

Can you tell me about the pivot to blonde?

It’s a career move. As an actor—I see myself as an actor now—I think I have to have my blonde moment. I have to have my Marilyn moment, and that will be the next body of work that comes out, which I’ve been slowly chipping away at. I really didn’t want to make COVID-related work, and I think going blonde was like, “Oh, this is like an emotional break, this is like Britney Spears’s Blackout, the Blackout album.” But also, if I can take on the persona of the “bombshell,” what would I want her to say?

How’s that new work going?

Really slowly. It was supposed to come out like two months ago, and my gallery is like, “How’s it going? When’s it coming out?” And I’m like, “Next month, next month,” and then another month goes by. But yeah, it’s just really hard. It’s just really hard to have stamina. I think it’s this weird combination of being really horny and being really sad—depressed and horny—so in my mind, it’s just there even if I’m not addressing it. It’s just there.