On the Photographs of Paula Court

Open nearly any exhibition catalogue or academic monograph about avant-garde performance in New York, and you’re bound to see one name pop up again and again in the photography credits: Paula Court. Since 1976, Court has fastidiously documented the city’s theater, dance, and music scenes. And yet audience members rarely register her presence. She moves nimbly and stealthily while shooting, carefully capturing moments that emphasize the gestalt of a given performance piece.

I recently was talking to Stella Cilman—a curator and writer who has been in dialogue with Court for several years—about her incredible and lesser-known archive. Out of our conversation, it felt like a critical moment to focus on Court’s enormous impact on avant-garde art in the city and start to dig into some of these materials. Cilman’s piece pulls from these personal materials to tell the story of her legendary practice, and relies heavily on first-hand oral history interviews that she conducted with many of the artists whose works Court has photographed, including Richard Foreman and Sarah Michelson. The resulting study is something of a critical paean—to Court herself, and to the downtown scene to whom she has been unwaveringly committed for almost fifty years.

– Ruba Katrib, 2023 EIR

I first met Paula Court in a cemetery, where a group had gathered to celebrate the life of the late artist Jack Smith. At the event, organized by Kembra Pfhaler and Artists Space in 2018, Court was busy with her camera, capturing a frenzy of performances by artists who knew Smith or would have known him, were he still alive today. As I arrived, I was unexpectedly enlisted to perform alongside artist Danny McDonald as his alter-ego Mindy Vale. I don’t recall the experience of performing that day, but Court’s documentation remains proof that it actually took place, a record for those who were not there, as well as for those who witnessed—or even participated in—the live event. Watching Court document friends and artists she had clearly photographed many times before, I immediately felt her central role within this community, one that her pictures have helped to define over the past five decades.

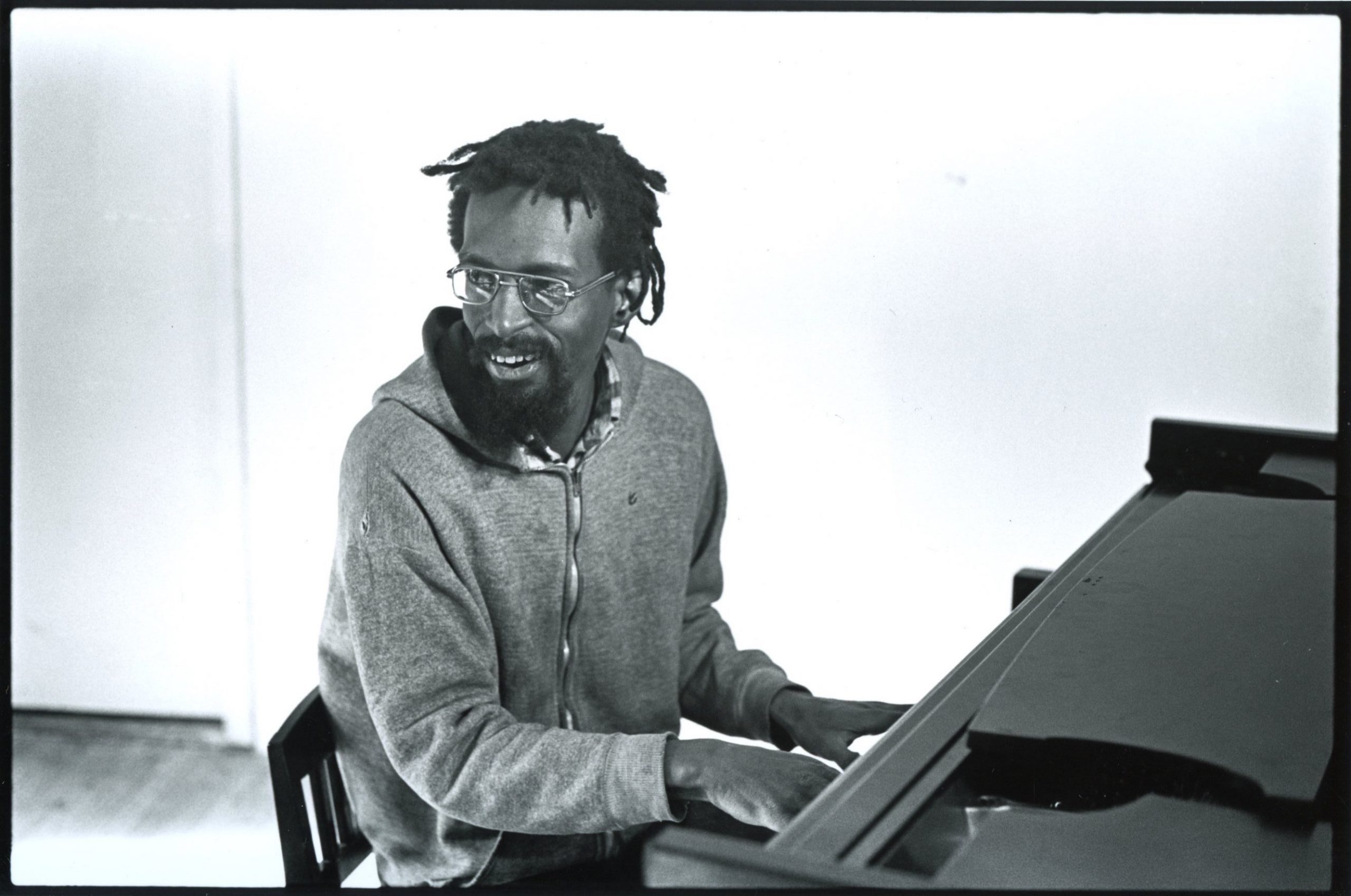

Court credits her upbringing as an important subtext for her life in New York. Born the eldest of ten children, she was raised in rural Appalachia. Her conservative, and at times punitive, Catholic education drove her to seek out something profoundly different as soon as she possibly could. But it wasn’t until a brief stint at SUNY Buffalo in her early twenties that she first encountered art. “If you landed in SUNY Buffalo and you were looking around and wanted to know about life or the mind, or both, it was all there. I would go to screenings of Tony Conrad and Paul Sharits and whoever was making movies, and saw the new music of Julius Eastman,” Court recalled. “I was an intensely dedicated student for my own needs now. And I was able to learn about what was happening in New York from afar.” On a visit to the city in the summer of 1976, she came across a flier in a deli advertising an unpaid assistantship for the choreographer Elaine Summers, who needed someone to document her performances. She had never used a camera before, but quickly taught herself to shoot and edit 16mm film in order to capture the movement of Summers’s dancers, lit by a multitude of 35mm slide projections in her SoHo loft. “It was the first time I thought about a dancer as a unit in a room on a floor. It was almost easy to do, but it taught me about movement and stillness,” Court recalled. Taken by her exacting eye, Summers encouraged Court to shoot still photography around the neighborhood, providing her an hourly wage and free film. On the corner of Mott and Broome, Court would stand for hours at a time, capturing incidental activity as it took place on the street. Summers was thrilled by what Court brought back and instructed her to assemble the snapshots into slideshows, which Summers projected as scenography behind her dancers.

The following year, Court moved into a ground-floor loft on Broome Street in SoHo, an area already well populated by artists of an earlier generation. She landed near the “Broome Street Building,” as she calls it, where Richard Foreman, Jonas Mekas, and Jack Smith all resided. It was here that she witnessed the ad-hoc improvisation of celebrated performance artists and saw the most recent underground films. Her social scene revolved around the group of artists and musicians who she worked with and served food to at the artist-run restaurant FOOD, founded by Gordon Matta-Clark. The popular spot was more than a restaurant. It was a place where artists could gather and eat culinarily adventurous and affordable meals together. Court has many fond memories of making sandwiches alongside no-wave musician Robert Appleton for luminary clientele like John Cage and Merce Cunningham. With Appleton and her best friend Rhys Chatham (who together were the band The Gynecologists), she frantically attended art events and concerts across the city in her time off, taking photos of everything she saw—sometimes for money but more often not, frequently giving her prints to artists for free. When I asked her why she gave away so many of her photos, she bluntly told me: “I wasn’t aware of power in art yet. I was naive and looked at this as a study, my education, including working in a food restaurant and putting up posters for events. I knew I was in the middle of something exciting and I wanted a place. And I knew I didn’t want to leave.”

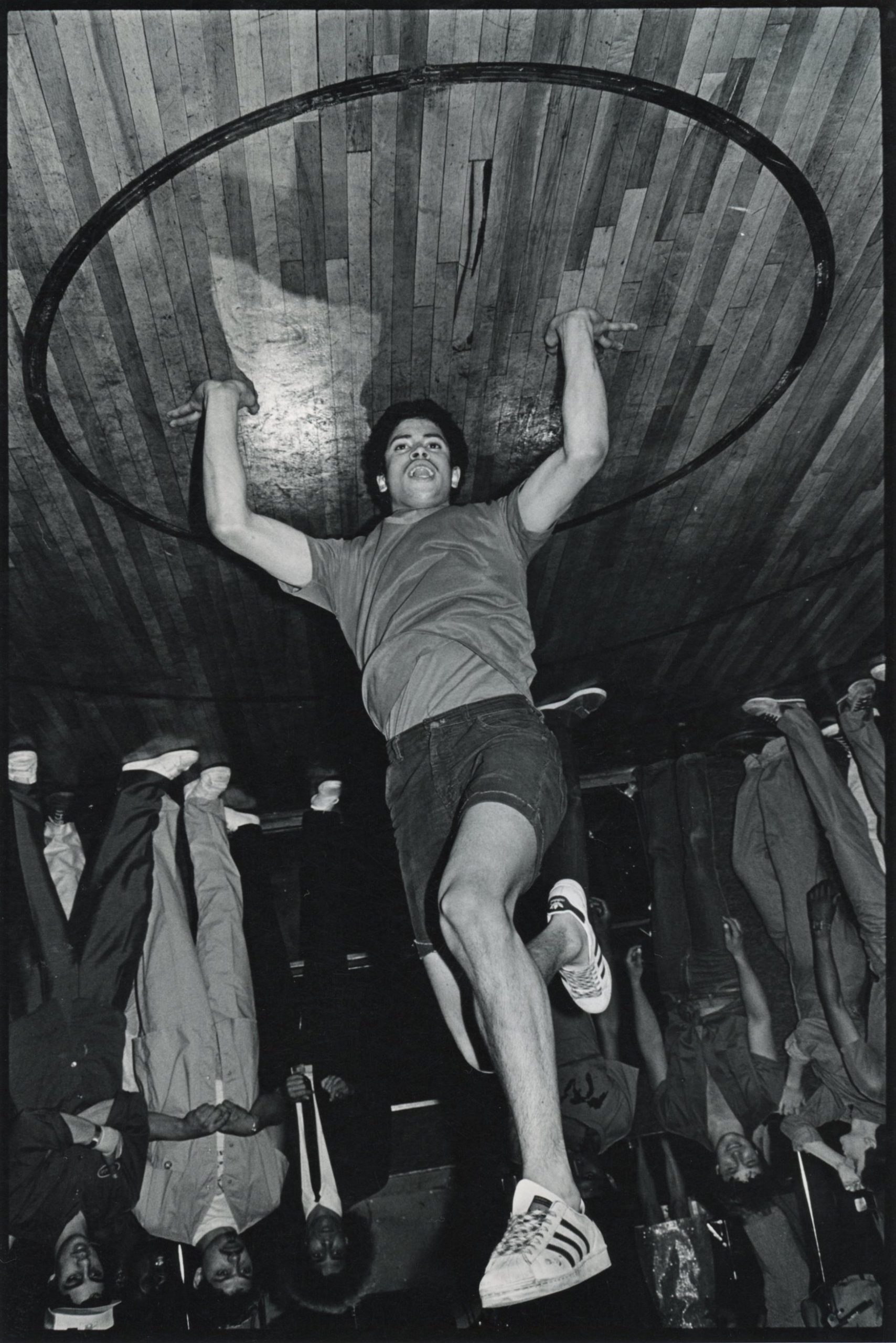

Court was a bridge between generations, photographing anarchic happenings in lofts as well as performances at newly established institutions popping up around Wooster Street. 1977 was a boom year for non-profits; NYSCA funding was plentiful, and organizations like Anthology Film Archives, Global Village, Collective for Living Cinema, Franklin Furnace, Artists Space, the Performing Garage, and The Kitchen accelerated the transmission of experimental work inside increasingly formalized settings. In the fall of that year, the directors of The Kitchen—Bob Stearns, Carlota Schoolman, and Garrett List—left without notice and were replaced by three twenty-four-year-old artists in Court’s milieu: Eric Bogosian, Rhys Chatham, and Robert Longo. Court made herself available to help with anything she could. Knowing she could take good photos, Bogosian hired to document his dance program. This new cast of characters, Court included, referred to themselves as “The Kitchenettes.” When I spoke with Bogosian about this time, he mentioned: “On the one hand she was capturing the older, established avant-garde—like Simone Forti, Meredith Monk, Kenneth King. But I brought all these young dancers in so she was also capturing the new guard—people like Bill T. Jones, Molissa Fenley, Karole Armitage, Grethe Holby. It was a completely different group of people. Every form of performance art eventually shook out to be either a kind of theater, or music, or dance. And even though we were all coming from different aesthetic fields, there was this sort of unification because we all knew each other.”

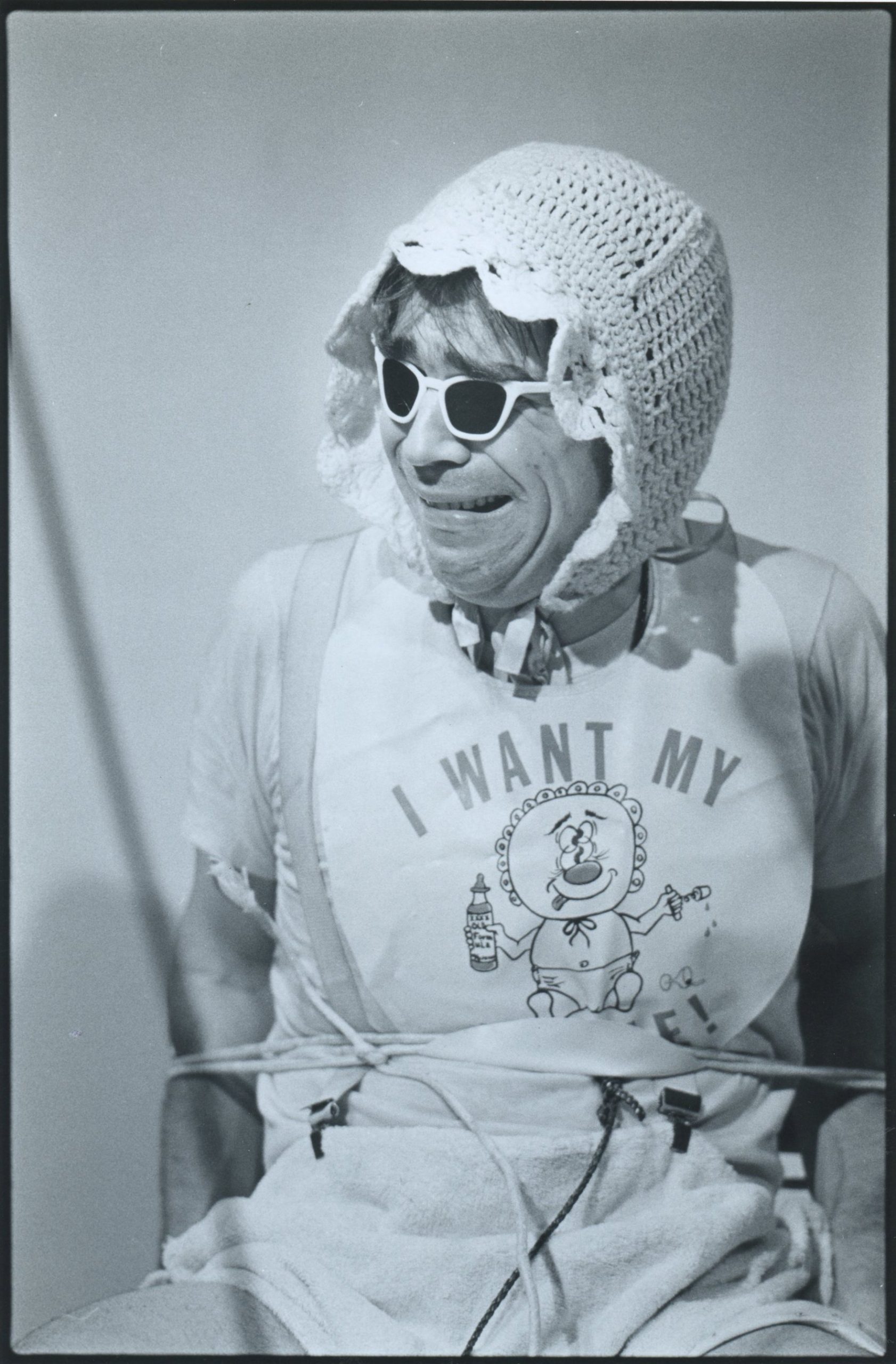

Court quickly established her crucial role amongst the many communities forming downtown. Her documentation, she felt, was a valuable service she could provide to artists, and a way for her to more wholly access their work. Throughout the 1980s and ’90s, Court photographed so much and in so many different fields that even she has trouble keeping track of her output. At concerts, parties, gallery openings, and in artists’ studios, she documented artists and cultural icons such as William Burroughs, Jean-Luc Godard, and Akira Kurosawa, Andy Warhol, Keith Haring, Mike Kelly, Mike Smith, Laurie Anderson, Robert Longo, Cindy Sherman, Richard Prince, George Clinton, Tom Verlaine, Lou Reed, Fab Five Freddy, James Chance, Patti Smith, and Afrika Bambaataa. The list is endless. And, while the dizzying breadth of her subjects is a remarkable feat of the archive, more interesting is the intensive manner in which she worked with a smaller group of artists across decades—the Wooster Group, John Jesurun, Eric Bogosian, Jo Andres, Richard Foreman’s Ontological-Hysteric Theater, Michael Smith, DANCENOISE, and Sarah Michelson, among others, with many relying on her documentation exclusively. Their experiences working with Court are reflected in the many conversations I had with these artists while writing this piece. The sum of these discussions reinforced not only her near omnipresence within the scene—she was always there ready with her camera—but also her unique ability to enter inside a performance while remaining curiously inconspicuous. Her photography exposed these artists’ ephemeral and, at times, unseeable work to a wider audience. But most importantly, she invented a version of the live event for the artists themselves, whose delayed perception was necessarily altered by her documentation.

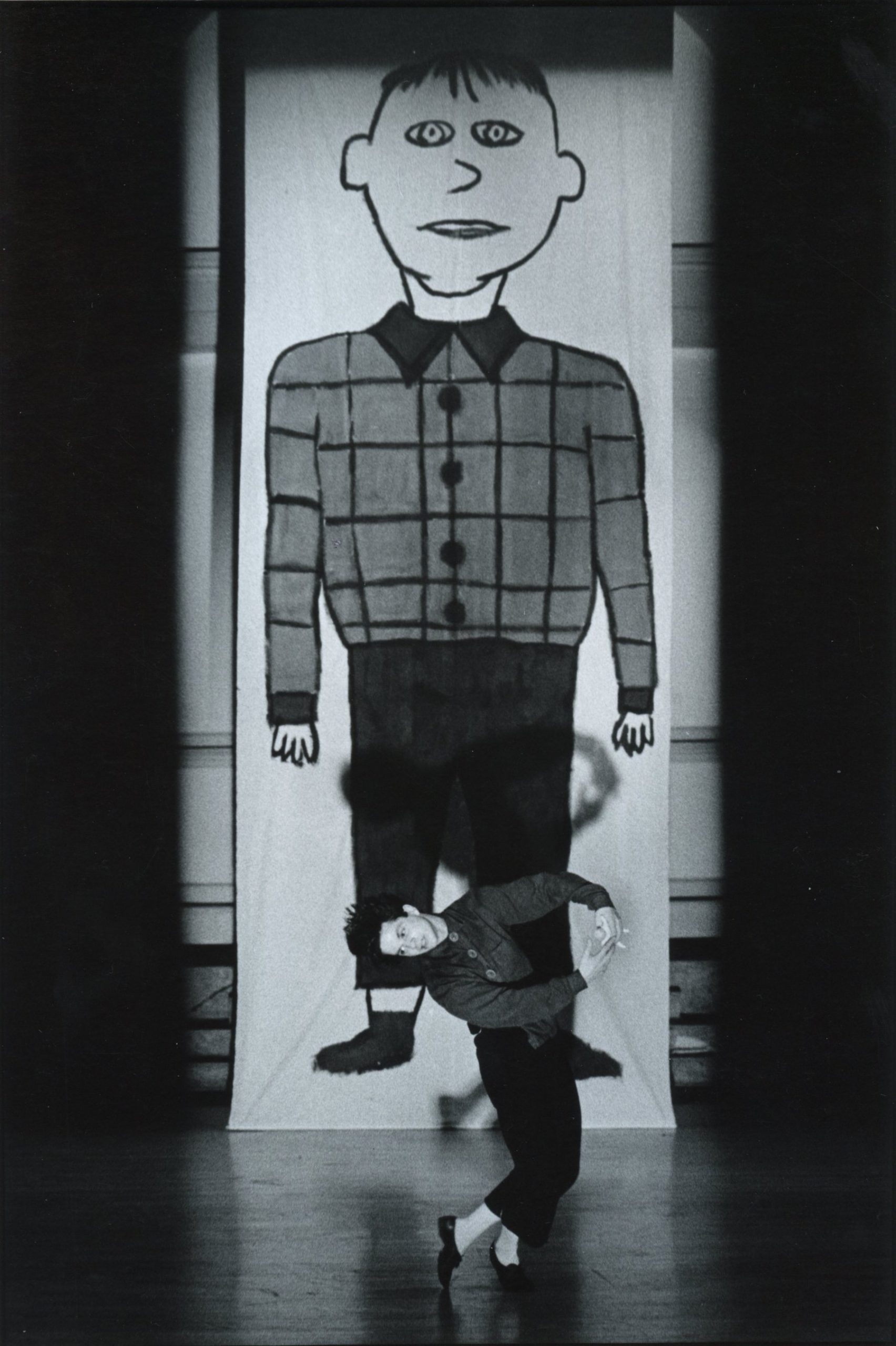

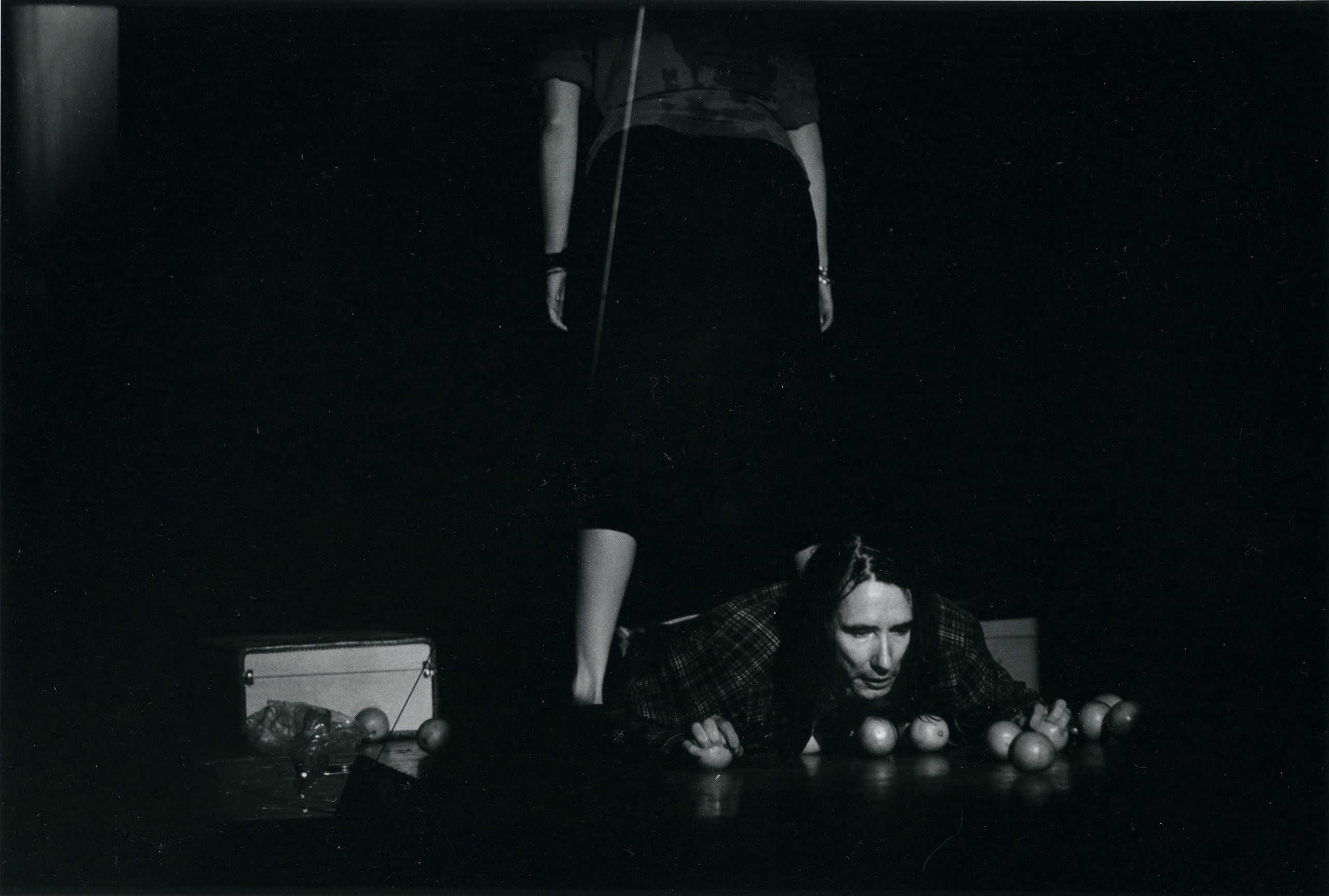

In performance, the role of documentation is particularly significant, and while its use for subsequent historicity is self-evident, less often remarked upon is its use for artists’ self-understanding and development in the moment. Often present for long stretches of rehearsal and returning to shoot and re-shoot multiple performances of a single work, Court developed a method defined by an enduring intimacy with the artist, whom she engaged with throughout the making of the work. As the artist re-articulated their vision over time, hers developed alongside it. Absorbing so many practices at once, she was able to communicate liveness with an acute specificity. She often took hundreds, if not thousands, of pictures during a performance, allowing the artist to see their own work with deeper clarity. Throughout the 1980s, she shot the arduously physical and narratively scrambled plays of John Jesurun. For him, her documentation was an essential part of his working process. “When she showed the images to you, you’d go: ‘Oh my god, that’s right. How did you notice that?’ She would see things that you hadn’t,” he noted. “Her photography was really part of the process of making something. Because everybody would look at it—me, my actors, the lighting designer. And we could see if we were getting it right.” As Court became well-known in the performance world, her eye gained traction as a marker of quality to artists. “If you were an artist and Paula agreed to take your pictures, that was a very big deal,” said Jesurun. “That [her eye] meant your work was actually being seen from the right point of view. Whatever she saw, that’s what it was, and how it should be seen and presented.”

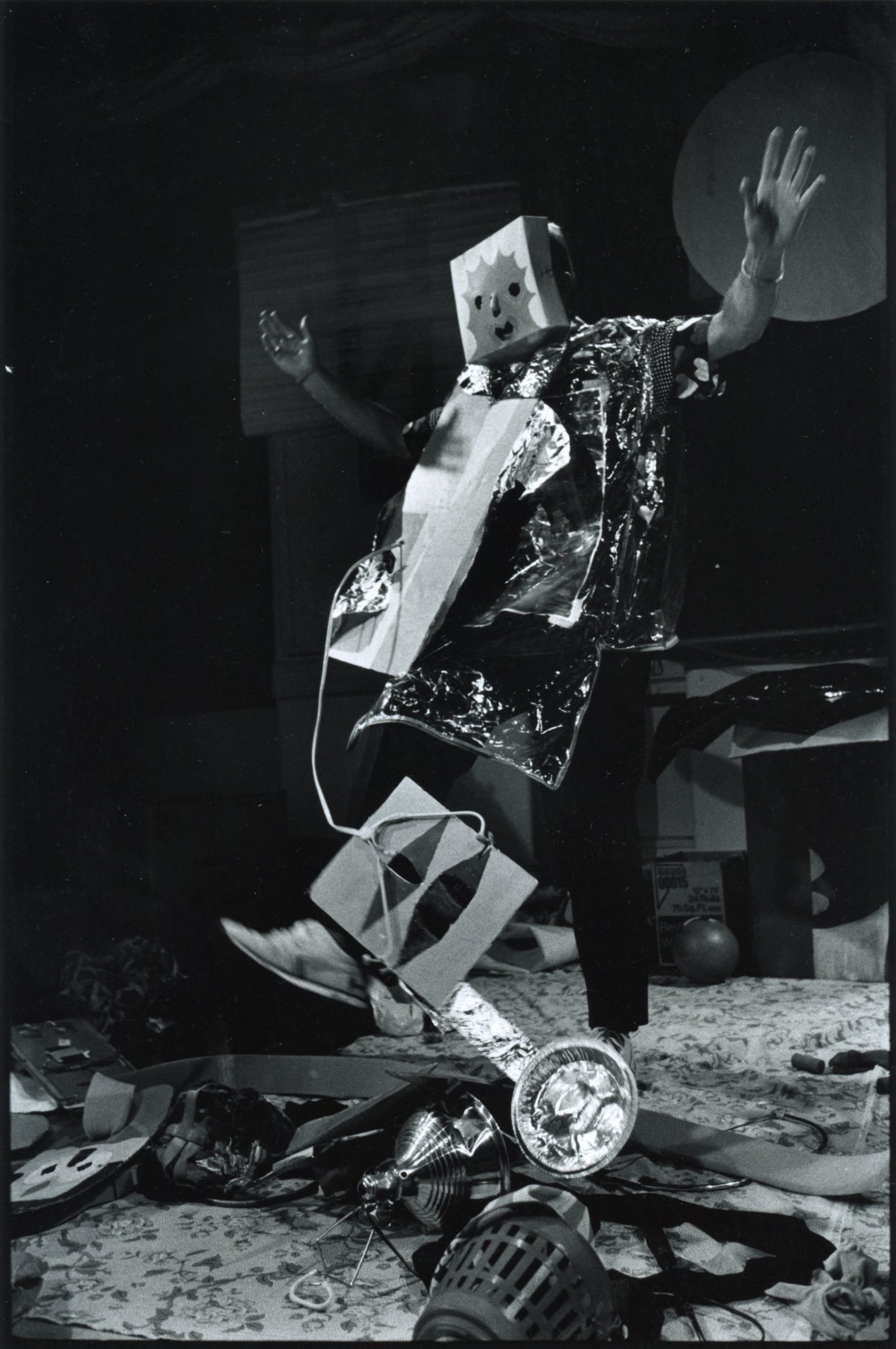

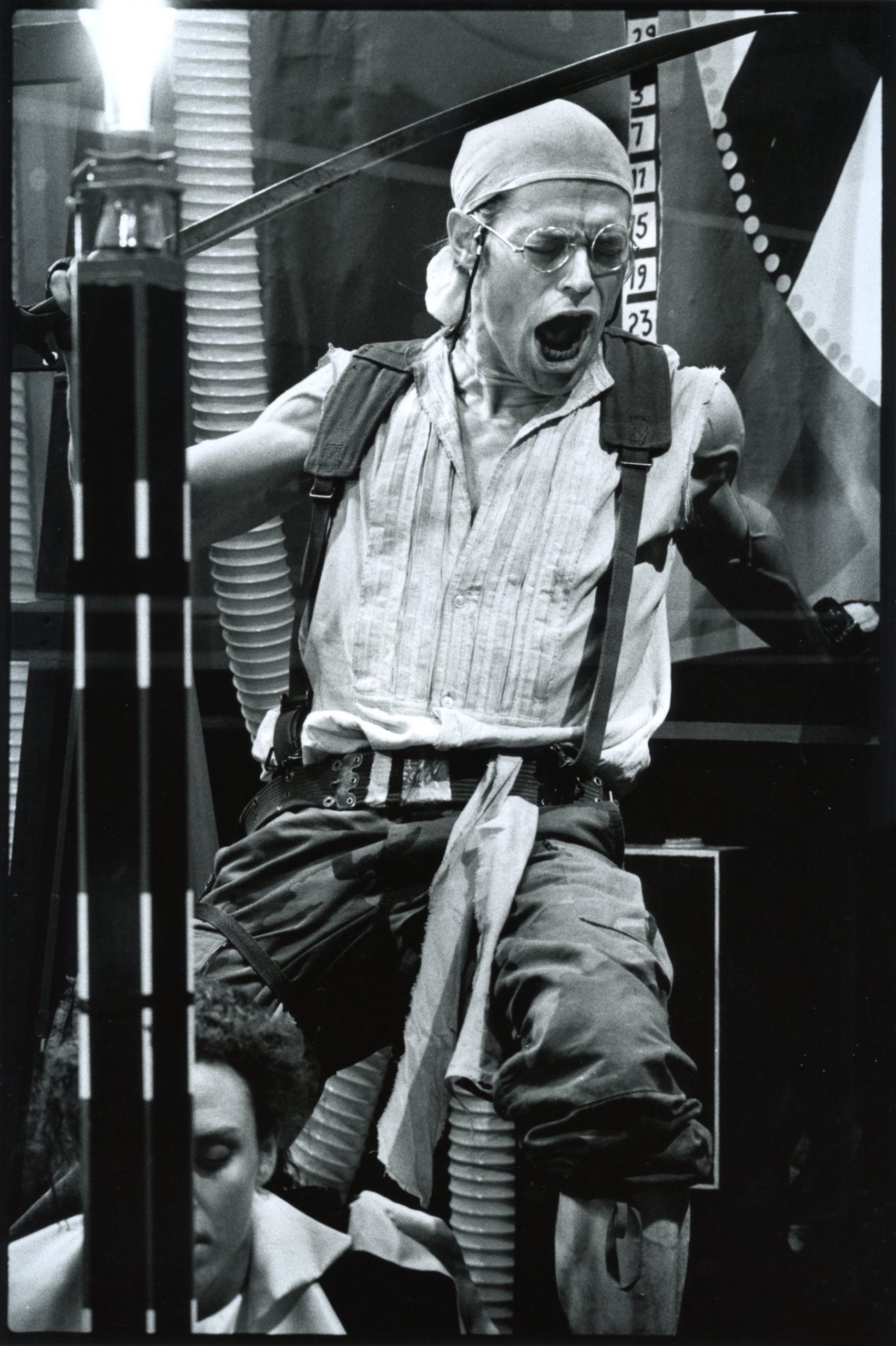

Court once told me she aims for her pictures to function as an immediate representation of the live event. She wishes to “reduce” the essence of an entire performance into a single shot, in the hopes of relaying the experience of being present. People who have worked with Court over the years attest to her intuitive, understated approach—a special combination of invisibility and closeness, of going unnoticed while remaining hyper-present. After working with legendary photographer Babette Mangolte throughout the 1960s and ’70s, Richard Foreman hired Court to shoot the ragingly unpredictable drama of his Ontological-Hysteric Theater for the next three decades. Watching her photograph his plays from the back of his small theater, Foreman noted, “Her pictures were very clear, simple, and she didn’t try to impose any kind of impressionistic ideas. She just shot it. I never believed in talking too much—either to my actors or photographers. The results are either good or they are not, and if they are, you keep working with them without talking about it.” Between the onslaught of explosive verbiage, Court quietly captured Foreman’s performers as they, at times belligerently, stumbled through reason and action. The experience of photographing Foreman’s work, she told me, “was the most exciting thing I have ever done; translating Richard’s plays to 2-D, vis-a-vis his brain. It was hard, because things were flying all over the place. But it kept me there and it kept me alive. That’s romanticizing it a bit, but in terms of image-making, it was the excitement of understanding that Richard was involved in the pleasure of non-sequiturs. And that was what my life was like—in New York and where I grew up—extreme chaos. I felt understood by the work.”

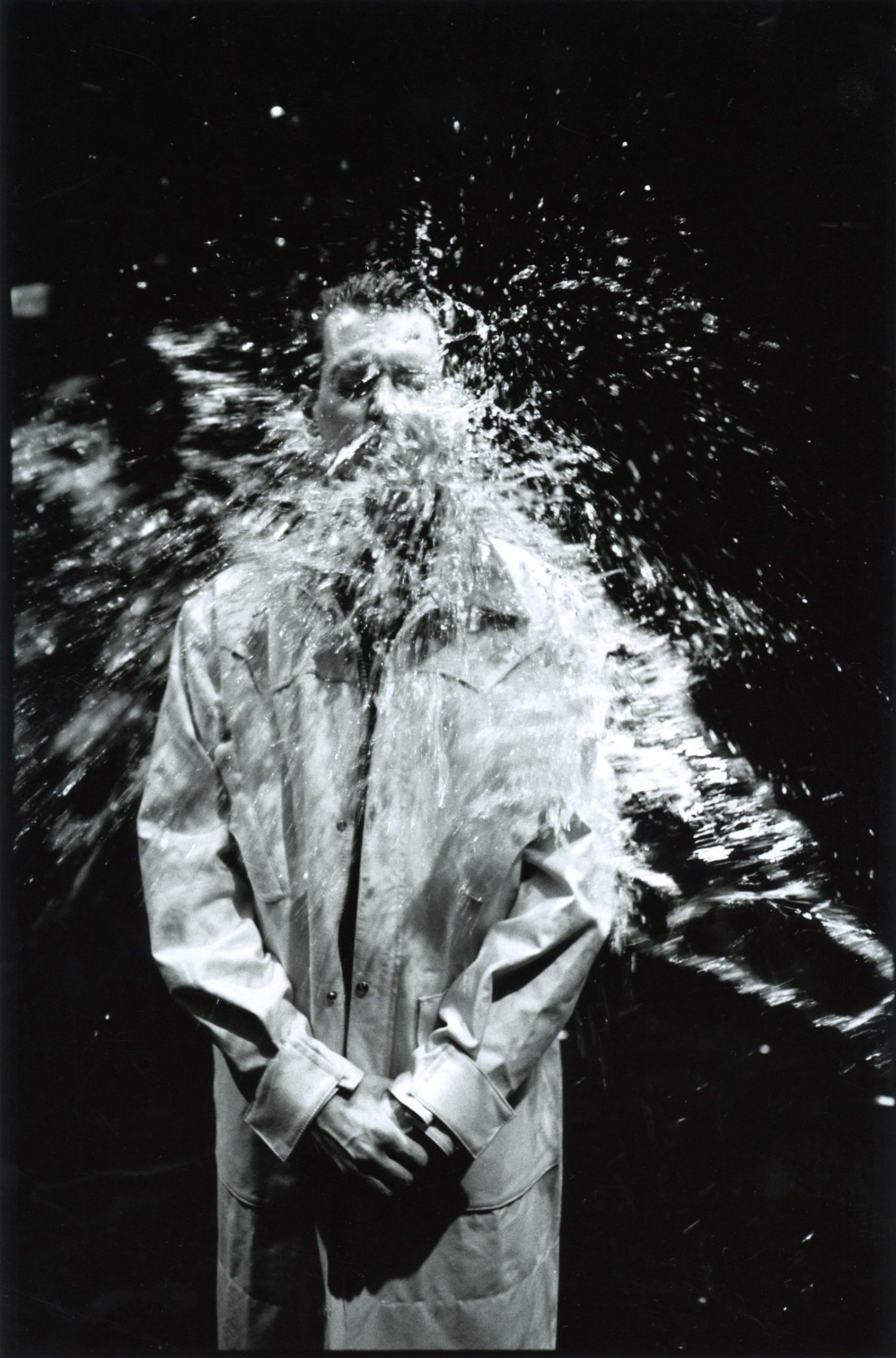

Of course, the prospect of capturing “live art” remains contentious for artists dealing in the ephemeral. The potential inertness of still photography always runs the risk of over-determining a moment or cheapening it. Performer and member of the Wooster Group Jim Fletcher said, “It’s notoriously hard to do justice to theater when translating to photography or video, maybe because it’s already framed, but for the live event not for the picture. Theater has already been transformed to some kind of unreal, that’s part of its reality. So, when film does yet another transform[ation] operation on it, it doubles back, it becomes tawdry or very drab looking.” Instead, Court’s photos access a subterranean psychological space that transcends any particular aspect of a given scene—the single gesture of an actor or a particular architectural detail near them. Her purview emphasizes the gestalt, embracing all the coincidental, chaotic, and awkward natures of people and things as they happen to interact. “Obstructions” to the composition—a face or a body in partial view, cleaved by scenographic elements—form the image’s underlying structure. An individual’s face becomes fixed to the forms that surround it, rendering the body as a sculptural element and sublimating individual personality to the character of the total visual field. In a photograph of Steve Buscemi in Jesurun’s play Sunspots (1989), Court caught the actor mid-splash, his face nearly disguised by liquid’s arrested motion. Though they felt that this was the image that most directly communicated the work, both Court and Jesurun were met with resistance by publications who argued that it was too difficult to identify the person in the photo.

Outside her role as photographer, Court has acted as an advocate for artists, fiercely defending their (and her) right to control the public image of the work, often to the chagrin of institutions that hire her. Always sensitive to the weight of posterity, her contractual agreement with the artist re-enforces this imperative: she and the artist share the rights to the photograph with its reproduction solely dependent on the artist’s consent, a measure to safeguard their agency in representing their work. The artist can then do anything they want with the image, as long as it is never cropped nor reproduced with text over it. Even more unusual is Court’s demand that publications pay the original author of the represented work at least half the amount she received for the photograph’s reproduction.

In the late 1990s, Court began a near thirty-year collaboration with choreographer and artist Sarah Michelson. Already sympathetic to her sensitivity around images, Court made it clear from the start that she would handle any institutional demands placed on Michelson regarding documentation. “She would do a ton of work—pages of emails between her and the institution—to contractually ensure that she and I owned all of the photographs we took during the shoot except for the limited selection we approved. It’s actually genius, and totally unconventional,” Michelson said. Foreclosing a traditional arrangement, wherein all of the images become the intellectual property of the institution, Court relentlessly negotiates a favorable agreement on the artist’s behalf, often withholding unapproved views—privileging her loyalty to the artist over the increased visibility of her work.

Michelson noted, “Paula is not a spectaculator and she is not gauche. She is extremely ethical. So there is absolutely no way she would promote a career of her own off of the back of her images of others. And that is also what makes every performance artist—who is so vulnerable because it is their body in real time—trust her.” Though she has been published in a number of performance catalogs, art publications, and rare books, and is well-known in select circles as the premier documenter of avant-garde performance in the late twentieth century, Court remains an obscure figure within the history she helped define through her iconic images. And while she contributed immensely to the underground activities she documented, she never profited off of any subsequent commercialization: not due to lack of talent, but because she was unwilling to allow personal ambition eclipse her commitment to artists and their work. In her rent-stabilized yet precariously-leased apartment (where she has resided for over forty years, developing prints in a makeshift closet darkroom) Court lives amongst stacks of banker’s boxes full of negatives, prints, and ephemera. The material, much of which has not been developed or digitized, contains an entire history—one that depends on the photographic record for its continued reception.

When I think about this era in New York performance history, which has been endlessly mythologized in images and literature as a period of free experimentation no longer possible today, I can’t help but enter the perilous realm of nostalgia. After all, this mythos is why so many of us moved here in the first place. But it is in her photos, and the eccentrically singular personality that comes through them, that I also realize Court, herself, could only exist in this time and this place. The legacy of her archive remains uncertain, but at present, inestimable value surely lies in Court’s forensic devotion to the singular, irreproducible moment—documenting so many, like her, who dedicated their lives to these now infamous practices.

Stella Cilman lives in New York City. At Artists Space, she has worked on exhibitions of artists such as Jack Smith, Art Club 2000, Bill Gunn, Adrienne Kennedy, New Red Order, Milford Graves, and Yasunao Tone, among others.

All of the direct quotations come from a series of conversations conducted by the author.