Rosalind Nashashibi’s Bachelor Machines

This essay inaugurates Topical Cream’s new collaboration with Liste Expedition on their “Writers’ Picks” series. The project invites female-identifying writers to contribute texts corresponding to artists of their choosing from the Liste Expedition universe. Each “Writer’s Pick” will be published on Topical Cream and Liste Expedition every other month throughout the next year and will range from essays to interviews to relevant exhibition reviews.

Men come together, men drift apart. They fix their eyes on one another or avert their gazes. Their bodies work together in concert, but their physical interactions are often triangulated by machines: scaffolding, a director’s dolly, a scrim, or a malfunctioning door hinge separate one man from the other. Sometimes, the camera—itself a machine—casts its gaze on them, lingering on the cicatrice on a sailor’s hand, the denimed pelvis of an Italian youth, or the pensive movements of a middle-class Englishman seeking intimacy amidst the foliage of London’s Hampstead Heath. These images center the movements of male bodies, but they are rarely erotically charged. Instead, they represent the efforts of a filmmaker, Rosalind Nashashibi, to both document and deconstruct a homosocial milieu that, as a woman, she is usually unable to access.

Nashashibi was born in Croydon, South London, in 1973, to a Palestinian father and a Northern Irish mother. Her films evince the unsettledness of a life lived between two diasporas: moving peripatetically from place to place, she has recorded the quotidian interactions of subcultural communities throughout Europe, the United States, and the Middle East. The resulting films are open and nimble, never crystallizing into a single thesis or narrative. But they are also haunted by a sense of trespass. The activities that Nashashibi captures are frequently private, and she traverses the spaces sensitive to the fact that she is an outsider.

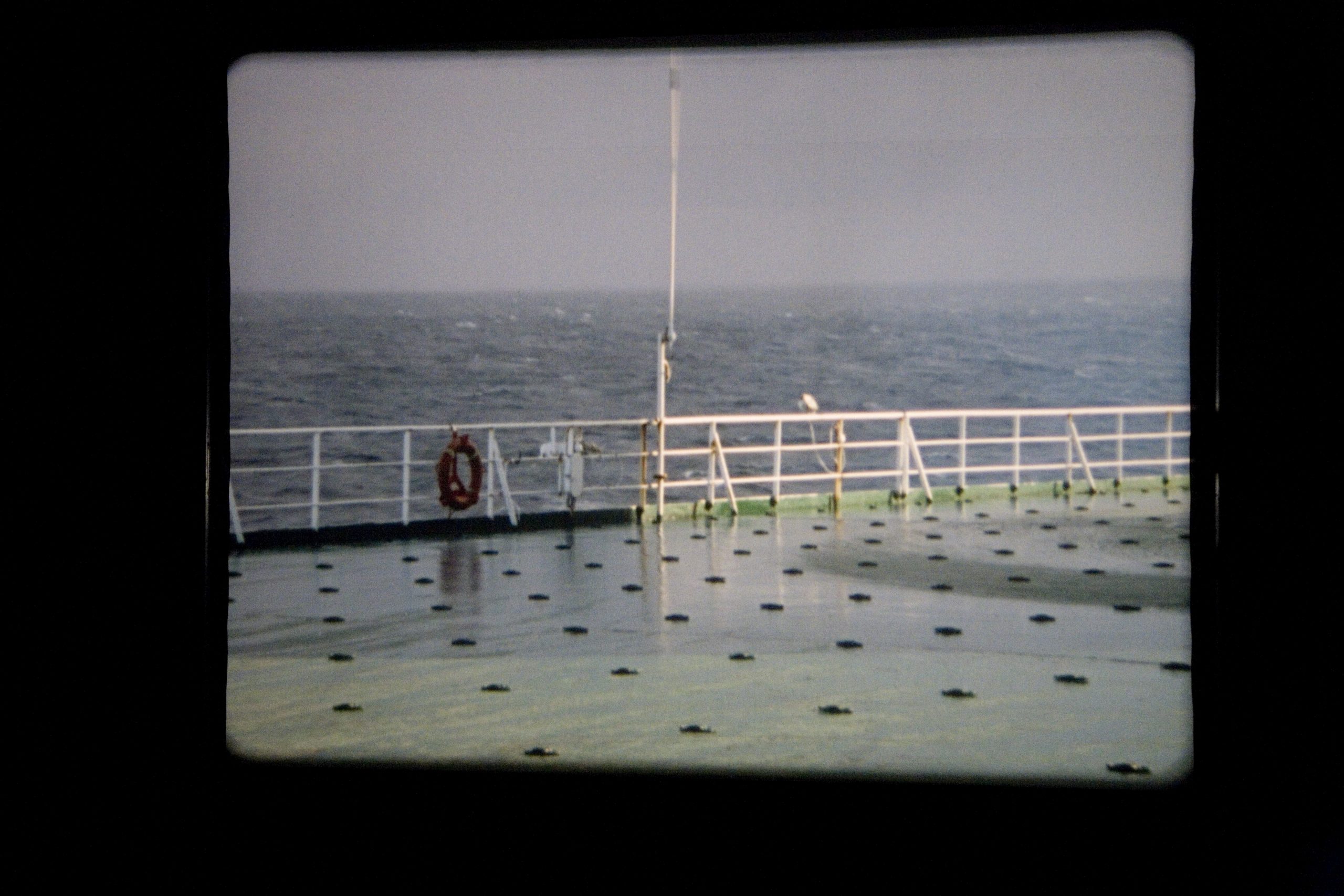

The spaces Nashashibi enters in films like Bachelor Machines Part I (2007) and Jack Straw’s Castle (2009) are normally reserved for men. Jack Straw’s Castle captures the furtive gestures of men cruising for sex in Hampstead Heath, before giving way to footage of other men installing a film set in the same park. Bachelor Machines, meanwhile, follows the all-male crew of a cargo ship, the Gran Bretagna, as it sails from Southern Italy to Sweden via Portugal, England, and Ireland. The film borrows its title from a term first coined by Marcel Duchamp in 1913 for his installation The Large Glass (also known as The Bride Stripped Bare by Her Bachelors, Even). Comprised of gliders, wheels, and grinders, Duchamp’s “bachelor machine” interacts with its counterpart, the mechanical bride, simulating encounters of flirtation and matrimony. Yet these simulations culminate not in procreation, but in entropy and death. Artists after Duchamp have re-envisioned the “bachelor machine” as a valiant rebel who favors the technological over the embodied even if it means inevitable extinction.

Nashashibi’s film strips Duchamp’s concept of its heterosexuality. No woman—mechanical or otherwise—is found within. It also strips the concept of its heroic language about destruction and procreation. Rather, Nashashibi’s intent in employing the term is humbler: to understand how machines both buttress and inhibit intimate interactions between men in spaces that are ordinarily unencumbered by the presence of women. Bachelor Machines splices footage of mechanized movements of the Gran Bretagna with brief scenes of crew members working and socializing. The scenes of labor are usually shot with a wider lens: we see two, sometimes three, men together, their bodies separated and framed by the apparatuses that constitute the ship. In a moment of respite, one hard-hatted crew member chats with another while sitting atop a large barrel or spool, playfully swinging his legs. Closer shots frame the men individually in recreational rooms and dining halls in their downtime. They talk together and laugh, but we are denied a full view of their interpersonal dynamics. Instead, Nashashibi’s camera zooms in on the chest hair and epaulet of a man who sits on a sofa while talking to a colleague off-screen, or the way another places his forefinger and middle finger on either side of his lips as he listens to the conversations of his friends. Greater, grander scenes of gathering are implied but never shown. Halfway through the film, we see a crew member walking down the “aisle” of the dining hall in preparation for an event. He closes the room’s double doors, refusing us—and likely Nashashibi herself—entry to the party that will occur soon after.

Rather than lingering in close-up on the men cruising in Jack Straw’s Castle, the camera tracks their ambulatory movements across Hampstead Heath’s wooded areas while they wait for signals from other men. But only the first five minutes of this fifteen-minute film focus on footage of cruising, as the daytime scenes of searching men are soon supplanted by nighttime scenes of male members of a film crew rigging a set in the park. The cruising men are solitary—the men on the film crew, meanwhile, come into close proximity, though their interactions are less intimate. Two men gel a light, while others move a scrim or lower an orange drop cloth. One woman, perhaps the “director” of this orchestrated scene, provides instructions to the men in her midst. In a review of Nashashibi’s mid-career survey at London’s Institute of Contemporary Arts in 2010, T.J. Demos framed the film set reveal in the language of trespass: it is, he writes, “as if the artist’s awkward intrusion into an all-male environment were being bizarrely theatricalized, the tables on her voyeurism turned.” But Hampstead Heath is not an all-male environment, per se. Anyone can enter. To my mind, Jack Straw’s Castle is less about the ethics of entering subcultural spaces, and more about the codes and gestures employed by subcultural groups—codes that are only legible to a select few. As a woman without technical training in filmmaking, I found the actions of the men cruising and those on the film crew to be equally impenetrable. I didn’t quite understand the specificities of either group’s signals.

The dense shrubbery of Hampstead Heath provides the cruising men cover for their itinerant pursuits, just as the vast expanse of the eastern Atlantic Ocean provides the Grand Bretagna’s crew a kind of social freedom. In both films, male intimacy is enabled by nature as much as it is by machines. This places the two films in sympathy with Nashashibi’s multimedia installation A New Youth (2013), in which an aluminum-mounted black-and-white photograph of a man’s denim-clad crotch hangs from the base of a narrow tree. The man’s legs branch off from his abdomen just as the tree’s limbs branch off from its trunk. A New Youth is, in part, inspired by the masculine iconography of Pier Paolo Pasolini. It also revisits Nashashibi’s 2011 installation Shelter for a New Youth, for which she placed a larger version of the photo-tree inside a traditional Emirati areesh house. Intermingling old and new, the piece is intended to comment on the revolutionary role of male youth in a post–Arab Spring world. Here, in lieu of Duchamp’s entropy, Nashashibi gives us fecundity—a sense that something still-to-come could be generated by the entanglement of man, machine, and nature.

Pasolini also serves as Nashashibi’s primary interlocutor in the film Carlo’s Vision (2011), which was installed alongside A New Youth in her solo show at the gallery Murray Guy in 2013. Departing from her previous films in its use of dialogue and narrative, Carlo’s Vision imagines a scene from Pasolini’s novel Petrolio, which was left unfinished at the time of the filmmaker’s murder in 1975. A silent man, Carlo, is pulled down the streets of Torpignattara, a neighborhood in Rome, on a director’s dolly by three “gods,” two of whom pontificate in voice-over about sexuality and urban politics in contemporary Italy. Their procession is intercut by images of a young heterosexual couple walking arm-in-arm down what appears to be the same street. Like the men in Bachelor Machines and Jack Straw’s Castle, Carlo is pensive and solitary, his body separated from the men in his charge by a machine. Gazing upon the couple, he seems to embody the predicament of Duchamp’s bachelor machine: set apart from a scene of heterosexual intimacy, he is encased by an apparatus that denies him physical communion with others.

Carlo ends the film pulled by the gods through an archway into the ruins of the Aqua Alexandrina, a defunct aqueduct built in the eighth century. Like Duchamp’s bachelor machine, his fate appears to be that of decay. And yet it is not Carlo or the aqueduct itself onto which Nashashibi’s camera casts its final gaze, but two narrow trees. Here, again, is an image of regeneration. Nashashibi draws on Pasolini’s novel, but she makes no attempt to finish his story. Instead, she gives us a glimpse of something else: revising the vision of her male forbearer, the final homosocial space into which she intervenes is the canon of filmmaking itself.

Elizabeth Wiet is a curator, writer, and editor based in New York. She is currently Director of Exhibitions and Fellowship at A.I.R. Gallery, Assistant Editor at Topical Cream, and Contributing Editor at Bidoun.

Banner image: Still from Rosalind Nashashibi, Bachelor Machines Part I, 2007. Courtesy of the artist and PM8/Francisco Salas.