Ridin’ High with Nancy Davidson

I first encountered Nancy Davidson’s work in a show at Cleopatra’s in Brooklyn called CARNIVALEYES. It was a very small gallery full of these large eyes, or asses—bulbous bilateral forms, covered in spandex, stacked and placed all over. The colors dazzled while the swollen forms both delighted and confused. It left a lasting impression. I later met Nancy and we ended up working on a proposal for her book Cowgirl. Connecting the dots, it dawned on me that I had met Nancy through a network that was made up almost entirely of women, and spanned multiple generations. I recently visited Nancy in her studio to talk about her new work, and to discuss the importance of alternative networks and how they have evolved through different generations, feminisms, and needs.

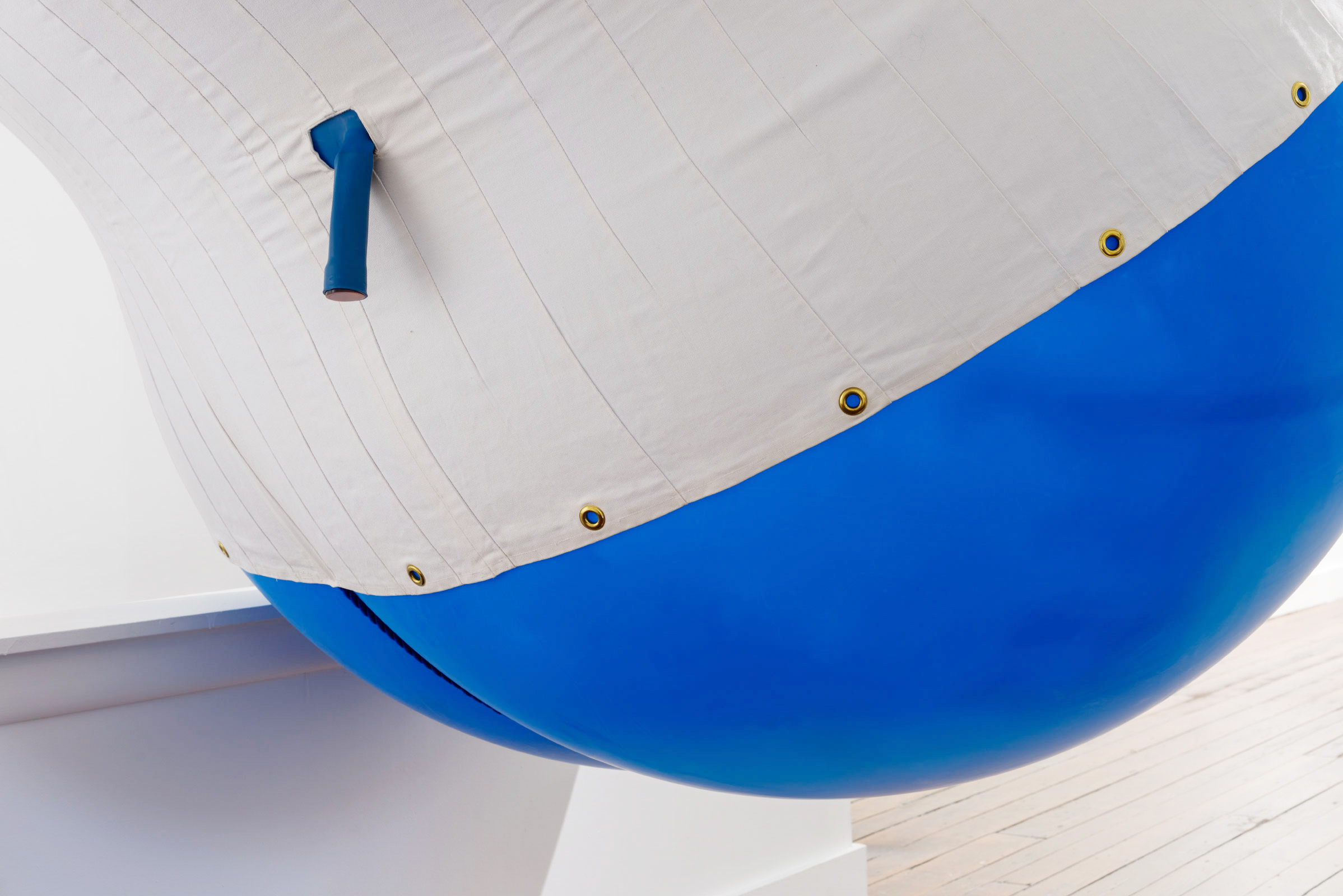

Nancy shows me a wall full of new drawings that she’d been working on leading up to her solo show, Ridin’ High, at Lord Ludd in Philadelphia. They’re gestural drawings of what appear to be soft bulbous tubes tied up in knots.

Riley Hooker: Tell me more about the knots.

Nancy Davidson: The knots are a new thing for me. They’re like the mind and the body all at once—they’re absurd. The absurdity is in having this twisted, kind of knotted form, riding high. They’re put up on this pedestal which is also called a palanquin—this carrying device for the privileged. Like a lifted sedan chair. Across many cultures, people of privilege and women were carried instead of walked. You know the image. I started looking at ways of making these knots. They’re twisted and it’s what’s happening today. It does all kinds of crazy things, it doesn’t resolve in any way. It’s gordian.

I started twisting these long narrow balloons—the ones they use for balloon animals—in different ways and drawing them. I’ve been looking at this figure called Moko Jumbie. He’s a very powerful figure from the Caribbean because he can see over things—over borders, over boundaries. The figures I was working on a couple of years ago were all big eyes on these tall legs. I imagined these knots on top of tall legs, making them into a kind of absurdist parade.

A parade of un-resolve.

Yes, exactly.

Even though your inflatables are aggressive in their presence and scale, they also feel like they could just float away. How do you feel about their impermanence?

There’s a fragility to it. It’s just like all other life that comes and goes. It’s not saying I’m going to make this out of stone and it’s going to last forever and it’s going to be huge and it’s never going to be destroyed. It is not that.

Right, it resists this idea that power is in some way permanent. It’s disarming—there’s this really big, non-threatening, extremely attractive thing. It pulls you in, you become vulnerable, then you start to sense that there’s something uncomfortable, and very deliberate happening.

Yes it’s exactly that—stepping toward the audience. It appeals very quickly. It’s about a non-corporeal body.

What role have networks of women played in your work / career / personal development / maintaining your sanity as a person in the world?

It’s something that I have often thought about, since I was in graduate school in the early ’70s. I loved Eva Hesse’s work. I’m still so moved by the way that she worked with materials, her choice of materials that were soft and could be manipulated by hand. She was often photographed holding her materials, actually cradling some of her pieces. She was physically involved with them, changing her ideas as she moved them around.

When I was at the Art Institute in 1973 there was a huge blossoming of women’s work, and feminists. They hired all these women as visiting artists. Judy Chicago started up women’s sensitivity training groups and seeded a movement to start women’s galleries.

I met her through a network of women in Chicago—Nancy Spero, Joyce Kozloff, Ree Morton, Judy Rifka, and Barbara Kruger. All of these women were very influential and supportive of me. Nancy and Joyce have continued to support my work since then.

I moved to New York in ’79 after having taken a job at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, allowing my son to finish high school.

When did you consider yourself an artist?

I never thought of being anything different. My father was a Sunday painter and he encouraged me. By the time I was ten or eleven, I started going to the junior school at the Art Institute and it was basically my world. I was destined, destined to go to the Art Institute. It was my dream.

I grew up in a suburb near Chicago. I was supposed to go to the Art Institute but I became pregnant in high school. My parents never wanted to talk to me about sex and by the time I told them I was pregnant it was too late. They wanted me to give the child up, but I knew I wasn’t going to do that, and they said, “well, fine, then you’re done with us.” It was 1961, I was sixteen. I got married, moved to the city, and figured it out.

You really stuck to your guns from day one! How did you come back to art?

It never ceased, I did what I could. I took night classes at different junior colleges. Painting, drawing, whatever I could take, I took it. I finished my undergraduate degree in three years and got a BA in Education so I could teach grammar school. I never stopped. After receiving my MFA, my son and I left the Chicago area, because my husband, who was mentally ill, finally lost it and started being abusive. It was not in my worldview that a man is allowed to hit his wife.

At this point were you influenced by feminist politics?

Yes! Practically every woman that I knew was either divorced or getting a divorce. It was ’68–’73 and it was an unbelievably exciting moment. The heart of the women’s liberation movement—everything was happening.

Your story parallels a queer narrative in a lot of ways because you had this sort of “coming out,” got kicked out of your house, and had to form a semblance of a family outside of the intimate structure that you were taught to rely on. I can relate, and I think it’s a huge motivator in forming these networks and communities out of a shared political ideology, rather than a fixed bloodline or a proximity.

There’s an even stronger sense of community when you know that you formed it yourself. You have this drive to maintain it and also to fulfill what you’ve always known. Maybe you always knew this, too, that you were not a part of whatever “that” was.

Exactly. And rather than try to define “that,” I just wanted to find the alternative. What has it been like for you to watch the visibility of feminism increase?

It’s really fascinating, the changes that have taken place. In the ’70s many women were involved with a kind of diaristic approach to feminism. They saw themselves enmeshed in a story where they were the victim. I never felt any common ground with that. As feminism changed, women started using other ways of expressing that beingness in the world. For me, it had to do with humor in relation to bodies.

Well, and it’s also kind of commenting on this myth, which I’m still confused by, that women aren’t funny. Right? Which is absurd, it just doesn’t align with my experience in life at all.

Yes! And taking the humor, expanding it, and relating it to being a woman, there’s a lot of risk involved. There’s a lot of risk in taking on humor, and taking on that fragility in works that aren’t going to be around forever. They’re not identified as important, as male.

All of those things came together in the materiality of my work. There’s a long thread coming from Eva Hesse using latex—coming to these materials, they’re almost like “fuck you” materials. Like, I can make things that are big, I can make things that are funny, I can make things that are making fun of the body. Play with it.

This is a thread you see in Judith Bernstein’s work, too, with her huge signature piece, you know, where it’s like, “Fuck you, I’m Judith and I’m here and you cannot, not see it.”

Absolutely. Judith and I met when I started teaching at Purchase College SUNY in 1984. We taught together there and have been friends ever since. She did her work always. She didn’t show for something like twenty-six years. It’s an amazing amount of time. She saw everybody’s shows. She supported everybody. She just didn’t get down, you know? She wasn’t going to.

And neither did you! You never stopped.

No!

And that’s a part of that network—a family that supports this attitude.

When you see that in someone else and you see it in yourself, it’s not like you sit down and you make a bullet point list of all the shit that you’ve gone through to get where you are, but you know and this other person knows. That’s your family.

A lot of writers make references, but I’m wondering how you position yourself in the varied context of feminism?

I’ve made it a point to empty my mind of these distinctions, I always found it funny to put these words around it like first wave, second wave, proto… cyber, selfie…

…and white. Many younger feminists are critical of previous generations because it really centers whiteness. And so intersectionality, this idea that bell hooks has really propagated, which I think is so important, has become more urgent. Really resisting and revising that kind of whitewashing and including, well, everyone. It makes me think about these knots on the wall, because it’s an entanglement, right? Feminism is not a singular thing, because our identities are not singular things. It’s all entangled with race, class, gender, time, place, and whatever else. It’s all very sticky. I feel like that has become more known, and more visible and more present in our culture. Seeing these knots makes me think about this uncertainty and un-linearity being put onto a pedestal—from selfies to think pieces to really just the way that we exist in the world. Singularity has become one of those other modernist myths.

Yes that’s absolutely the way it is and I’m glad you mentioned bell hooks. I was in a feminist group that met at NYU run by Ann Snitow called Sex, Gender, and Consumer Culture. The group was formed after an earlier split over pornography, which we were for. bell hooks, Michelle Wallace, and Lorraine O’Grady were visitors. In the late 1980s the issue of race and class, this issue of whiteness and privilege—split up the group. It became clear that whatever brought this group together was no longer capable of holding it. When you’re trying to work something out in your head, you realize that you won’t accept certain conditions for what you can do, or what other people can do so you want to walk away from it. I think everybody at that point felt the same way. They didn’t see it as coexisting together, so maybe we can all exist, separately.

Yeah, it sounds like this collective investment in subjectivity.

Absolutely!

It’s the knot.

We could think of it that way—It’s a kind of inexplicable physics. It’s not the simple curve of a double helix, there’s many more places to turn and twist and I think that’s what came out of it.

So there was this chasm and it split, where did you go?

I went rogue. No more collectives, just do the work and my own readings. There was still a small group that did readings on deconstruction and Jacques Lacan but after that, I didn’t have any other groups to go to.

It seems like you were able to evade part of this conflict through abstraction. You’re clearly referencing the body in a really visceral way, but it’s abstracted to the point where it isn’t fleshy. The color palette comes more from references to pleasure and fun. There seems to be this dominant narrative that abstraction is some kind of neutralizing act, this is something that Sondra Perry has talked about. Your work abstracts things in a way that feels very productive because it’s super confrontational, it’s unapologetic. Not neutral.

Absolutely.

Riley Hooker is a graphic designer based in New York and is the editor and designer of Façadomy.