Lillian Schwartz: Pioneer of Computer Art

In our rapidly growing networks of social media, a dark suspicion underscores our digital footprints: Is that really the status you’re feeling right now? Is that really where you are? Is there really no filter on this photo? Validity on social media has more to do with an acquired approval via followers and likes than the accuracy of whether a post is “in real time” or a “latergram” or simply constructed for wit, laughs, or controversy.

The idea that our online selves are carefully curated avatars of who we want others to think we are in the flesh, has progressed over the past twenty years of Internet services providing peer-to-peer profiles, chatrooms, and sharing capabilities. “FOMO” (Fear of Missing Out) has entered our lexicon as a shorthand diagnosis for how important it is to not only generate content of ourselves for media, but to generate the kind of self-portrayal that would induce an anxiety of envy in others.

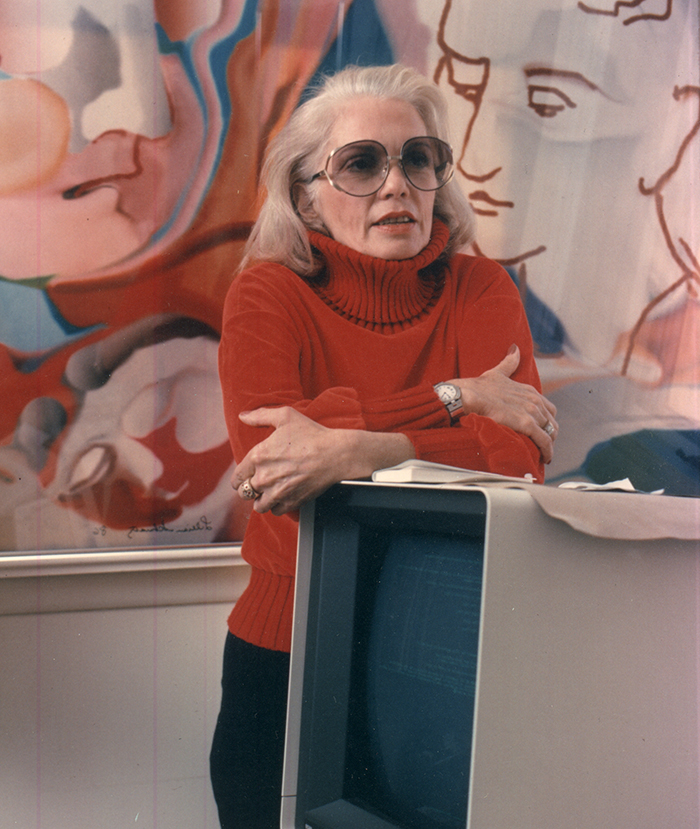

Magenta Plains has been exhibiting artists with large-scale, eye-catching allure since opening less than a year ago on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. The anxiety embedded in their recent show, Lillian Schwartz: Pioneer of Computer Art, arises not only from the desire to see the twelve catalogue pieces and eighteen moving image works in person, but also from actual fears of art missing out on art: this is Schwartz’s first gallery show, and at eighty-nine years old, her work is finally receiving dedicated attention as art done by her, whether as part of a collaboration or under a corporation’s copyright.

As a member of the collective Experiments in Art and Technology (E.A.T.), begun by engineers Billy Klüver and Fred Waldhauer with artists Robert Rauschenberg and Robert Whitman, Schwartz collaborated on art projects in the 1960s until attracting the attention of Leon Harmon with her Proxima Centauri (1968), a kinetic sculpture chosen as one of nine E.A.T. pieces for MoMA’s 1968 exhibition The Machine as Seen at the End of the Mechanical Age. Harmon, a visual perception expert at the renowned AT&T Bell Labs (“a breeding ground for Nobelists”), invited Schwartz to their New Jersey campus where she stayed from 1968 until 2002, an artist collaborating with engineers on developing tools, technologies, and possibilities for the future of computing capabilities.

In 1984 Schwartz used in-depth computing analyses to prove that Leonardo da Vinci used himself as the final model for his Mona Lisa. Causing a media sensation, the head of Bell Labs asked Schwartz, “Who are you and why aren’t you in the company directory?” Only then, after sixteen years of having worked there already, did she finally begin to receive a salary and a contract; previously as a Resident Visitor, she was an unpaid researcher—like a hugely influential, and deeply integrated, company intern.

Schwartz’s first lesson, when brought into Bell Labs, was coding. In 1968, a computer took up a whole room and was slow to output some commands. Ken Knowlton, debatably credited with having invented the pixel, was a graphics and programming engineer at the Lab. He taught Schwartz how to use his computer language BEFLIX (Bell Flicks), but because she was not a computer native, he built a new language that was easier for her, called EXPLOR (Explicit Patterns, Local Operations, and Randomness). Using these programs, Knowlton and Schwartz collaborated on her first moving image done at the Lab, Pixillation (1970). The film bleeds graphics into one another in blinding flashes of saturated colors, painting the mechanics of brain synapses or color-coding the inside of computer processing.

Often described as a “primal” viewing experience, the film is not shocking as much as it is enchanting. Played downstairs at Magenta Plains with a Moog soundtrack by Gershon Kingsley (one of the several soundtracks for the piece), it makes us ask, are trance and eroticism the same? Someone’s baby was fixated on the screen, kicking her legs in time with the climaxing music as the strobing light pulsated in crescendo. Stimulation is clearly the key to growth.

Similarly, Googolplex (1972) is sensory trickery. Made only in black and white, the techniques Schwartz developed were based on Polaroid inventor Edwin Land’s color experiments. By flashing the interchanging positive and negative spaces of the screen in rapid alterations of distorted graphics, Googolplex appears to cascade in rainbows as the brain cannot keep up with the progression of images. Not “primal” so much as “tribal,” the soundtrack is Schwartz’s remix of audio tapes from President Nixon’s visit to Africa, heavy with rapid drums that choreograph the flickering screen.

The influence of popular news and culture during the times when Schwartz was creating work is evident in the Lab’s quest to discover the boundaries of technology, as well as the commissions that came in for creating specifically new mechanics. MoMA commissioned Schwartz to create a Public Service Announcement for their new renovation. The Museum of Modern Art (1984) premiered at thirty seconds long after two years of computer graphics and animation work, funded by IBM. Although Schwartz won the first Emmy for a TV PSA, we don’t see such museum ads anymore, as they have been strangely replaced by static posters in subways and glossy pages in art-niche magazines.

Schwartz created artworks alluding to today’s anxieties before they could actually be understood, before FOMO came to be a psychological effect on our societal tendencies. Cave Painting, again using the grand past to accentuate the future, is an inkjet print of a computer graphic. A bison-like animal—hairy chin, tail, penis—leaps against a blur of blues and browns: time itself? A gradient rectangle displays: “What’s New.” The bottom text reads: “www.cave.paintings/html.” Today, this is seen as Outsider Clip Art, but Cave Painting dates from 1983–1984, even though Sir Tim Berners-Lee didn’t coin the World Wide Web until 1989.

Lillian Schwartz’s first solo exhibition closed at Magenta Plains’ Pioneer of Computer Art in October of this year.

Shelby Shaw is a writer in New York and Managing Editor of the art and literary journal Storyfile.