Female Genius: Avery K Singer

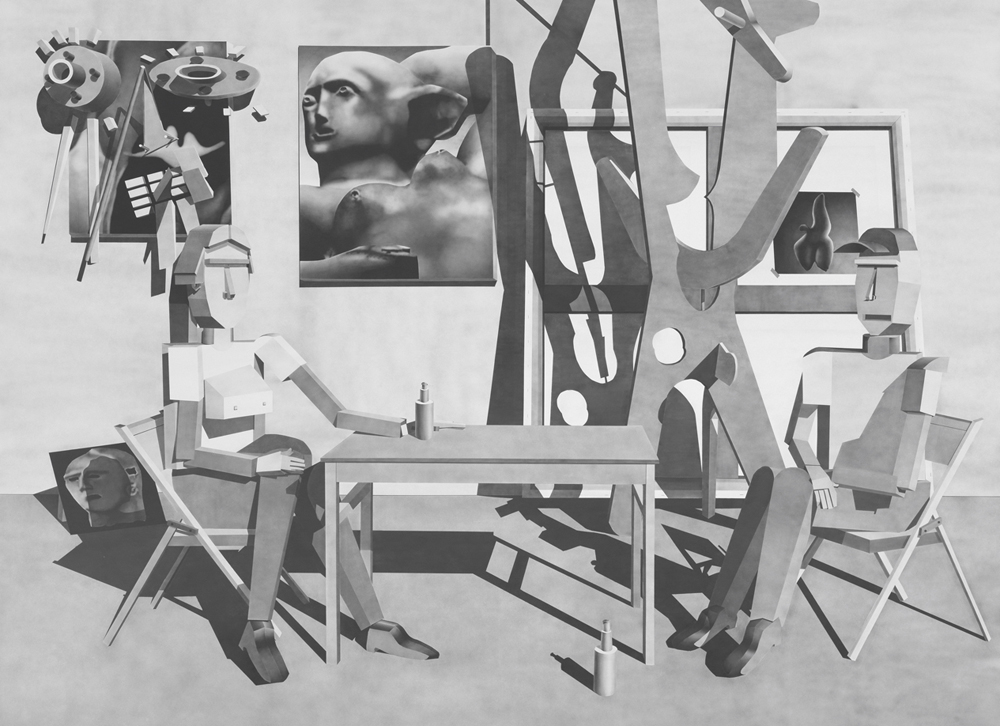

Avery Singer’s The Studio Visit (2012), a large black-and-white painting roughly two meters tall and two-and-a-half meters wide, shows two figures seated at opposite ends of a table, apparently participants in the awkward ritual of a studio visit. On view behind them is a selection of heterogeneous artworks. They sip at geometrically rendered beer bottles.

“I see the figuration as being semi-narrative,” says the artist, a twenty-eight-year-old New Yorker and Cooper Union graduate. “It’s kind of satirizing nostalgic tropes of how artists conduct their lives and careers.” While most American artists born in the 1980s have disabused themselves of certain inherited images of late twentieth-century bohemianism—rent-stabilized Manhattan apartments, for example—others persist: long, boozy gallery dinners, mutually supportive artistic communities, an abstract concept of genius. The uncritical performance of these myths becomes, in Singer’s work, is the site of a rich and generative humor.

Certain equally recognizable narratives of the contemporary artist, Singer notes, weren’t as well documented in the visual register: we don’t often see the contemporary artist executing a work of mediocre performance art (Performance Artists, 2013), or passed out on a table with an open bottle of wine (Saturday Night, 2013). “It started with an awkward studio visit and an awkward performance piece,” Singer explains. “I made paintings of that because I thought that, when you make a painting, you historicize everything that surrounds it.” The Studio Visit deals with the friction between, on one hand, the romance around maintaining a studio practice and, on the other, the economic reality of having to court curators, critics, and collectors. Just as the figures in the paintings are crudely generalized—the figure on the left-hand side of the table is identifiable as female by her block-shaped breasts and ponytail, while that on the right as male by his baseball cap—the particularities of the fictional scene are in dialogue with the stereotypical.

Like all of Singer’s paintings, The Studio Visit stages certain optical impossibilities: different elements of the image are abstracted, flattened, or brought into unreasonably sharp focus through the artist’s signature use of the 3D-modeling software SketchUp. The program is generally used to plan and design architectural spaces and is, in its basic version, free to download and use. “A lot of people in art school were starting to use it to plan installations,” Singer says, “so I started playing around with it and really loved making images with it.” She used SketchUp for several years before experimenting with translating the three-dimensional models onto a material surface: first drawings on paper, then airbrush paintings on canvas. “I kept experimenting with airbrushing, and it ended up very quickly growing into these really giant works,” she says. “But it took me three years of figuring out how to work, developing the language, and seeing what interested me.”

It was these large-scale works that constituted Singer’s first solo show, The Artists, at Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler gallery in Berlin in 2013. The following year, Singer’s first institutional solo show, Pictures Punish Words, opened at the Kunsthalle Zürich, where the paintings were installed on pairs of long steel rods screwed to the floor and ceiling. “I have a sort of reticence towards traditional modes of display,” Singer explains. “I also like to hang the paintings low so you don’t feel intimidated by them.”

Most recently, moving away from more conventional formats, Singer executed an ambitious project comprising a room painted in its entirety—walls and ceiling—in her trademark grisaille imagery. Presented by Kraupa-Tuskany Zeidler in the Statements section of Art Basel 2015, the untitled piece is a new iteration of Singer’s idiosyncratic style, this time pushed to the limits of its figurative legibility. A complex matrix of geometrical shadow-play is interrupted by the outline of a digitally generated face, its pixels loyally recreated, while at another point the electric-blue glow of an activated vape breaks the painting’s monochromy. The color, Singer says, is as much a reference to the blue glow of an iPhone screen as to the artist’s preoccupation with “this idea of capitalism producing desire for you.” At what point can an artist incorporate new realities into a historical mode, she wonders—“can you show an iPhone in a painting?” The work “ties into these Modernist modes of portrayal, but its technology is changing around us.”

Tess Edmonson is a writer and editor based in Berlin, where she is the assistant editor of art-agenda. Her writing has appeared in Texte zur Kunst, C Magazine, and Afterall online.

This story originally ran in PIN-UP Magazine, Number 19. Special thanks to Eva Kenny.